|

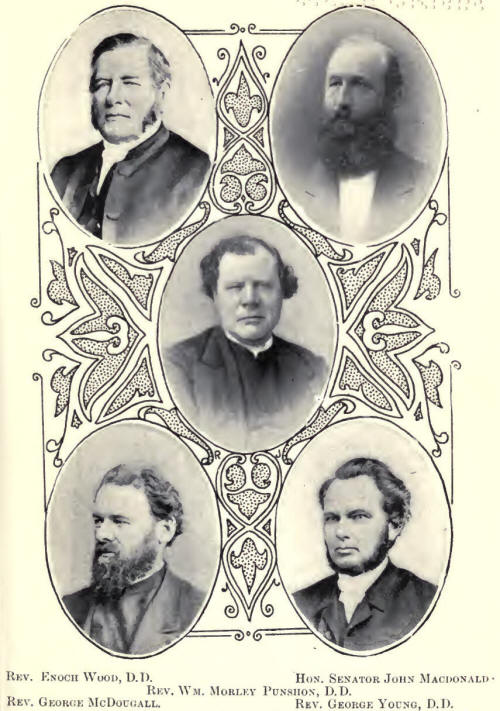

A FEW days sufficed for our

missionary gathering, and presently we were away, I to join the eastern

party and visit for a few weeks the scenes of my childhood. This was

pleasant in prospect, but when I had the privilege of travel- hug in the

company of such men as Drs. Punshon and Wood and Mr. John Macdonald, it was

to me a greatly prized opportunity. We embarked on the International at Fort

Garry, and soon were stemming the muddy, sluggish current of the Red. It was

a sultry afternoon, and Dr. Punshon, bitten on the hand by a lively

mosquito, came to me in his trouble; not only because of the pain and

swelling, but also to inquire as to the ineffectuality of the mosquito

netting he had on his hat.

Said this learned man, "I

took the precaution of purchasing some netting, and a lady friend arranged

it on my hat nicely; but it seems of no avail against these pests." I told

him that all the netting in sight arranged as his was would be of no avail;

and then, ripping it from its artistic setting on his hat, and borrowing

needle and thread from the stewardess, I made the netting into a sack which

came down over the Doctor's head and neck, and told him to put on his gloves

and fear no more. He was greatly astonished and most grateful, and wondered

that he had not thought of this earlier. The Doctor was full of questions

concerning the West, and as we were standing together on the steamer's deck

looking out on the plains of the Red River valley, he suddenly asked me how

many horses I had. I straightway began to count up on my fingers: there were

Moose Hair and Jack and Little Bob and Archie, and the two Browns, and Beaso,

and Wahbee, etc., until I had twelve, that I told him if he knew anything

about horses he could either ride or pack or drive, and that I had some

unbroken mares and colts running at large on the range. "My, what a stud for

a preacher!" was his exclamation, and as he was a big, stout, heavy man, I

drew up a little closer to His Bigness and said, "If you had my work to do,

Dr. Punshon, you would require seventy times as many as I have." Then he

laughed and said, "That is true, John, and I do not mind if you have a

thousand so long as you do your work."

At the boundary line we met

the Customs officer. My party, desiring to go ashore, left their keys with

me and asked me to look after their baggage. With us but not of us was a

tall man named Snider, who came and put his carpet-bag beside my pile, but I

moved it away and suggested that he had better look after his own luggage.

When the Customs House officer came I stood beside my stack of valises and

grips, and jingled a half dozen bunches of keys in my hand, ready to open

everything if need be. "Who do these belong to?" he inquired.

To those gentlemen you met on

the gangway and myself," I answered, and he chalked them through without the

opening of a single one. "Whose is this'?" was the next question, pointing

to the carpet-bag I had fortunately moved away from our heap. "Mine," said

the tall man. "Open it," came the command, and the tall man opening his bag,

the officer put his hands in down to the bottom and brought up a nice bundle

of martin skins, and quietly putting them under his arm, moved on. The tall

man was visibly disturbed at this confiscation, and I read him a lesson on

attempting to smuggle. I was glad enough that I had moved that bag from our

belongings.

Reaching Grand Forks we were

told that the boat would go no farther, and that all passengers would now

proceed by waggon. Behold us, then, in a little while crowded into

high-seated, low-covered, springless waggons. Here, while looking after the

luggage of my friends, the Doctors, I was crowded out of their company and

jammed into that of a strange lot of fellow- passengers. As we rode over the

rough prairie trail the jolting was terrific. To sit with heads bowed and

legs dangling in the air was growing to be something like purgatory, and I

very soon began to agitate for a change. By taking out the top sides of the

box and lowering our seats that much, we might make ourselves passably

comfortable, but when I mentioned this to the driver he at once with an oath

declared, "You shall do no such thing." I persisted in my demand, but still

the stubborn driver refused. However, at the first stop we made I had my men

ready, and we adjusted the seats while the driver was looking after his

horses. On his return he was furious, but I gently told him not to worry,

and assured him that we could go on without him, even if we had to leave him

bound hand and foot to do so. Seeing we were in earnest, and that all his

cursing and fuming would be futile, he gave up, and before the day was over

had to admit that my plan was the best. To Dr. Punshon that long day under

such circumstances was excruciating.

At dusk we crossed the Red

River at Georgetown, where more than twelve years before father and our

party had camped for some days when we were en route into the north. We

still had twelve or fourteen miles to do before reaching the railroad at

Moorehead, and had it not been for Mr. Macdonald's forethought we would have

hung around an atmosphere of smoke and mosquitoes for hours; but he had

telegraphed for a waggon for our party, and there it was standing and ready

for us. However, we were very hungry, and on inquiring were told by the big

German who owned the place we were stopping at that they had no food cooked.

Then Mr. Macdonald asked if they had bread, and the answer came back, "Oh!

yes." Again he asked if they had milk. "Oh! yes." "Then please give us some

bread and milk," and soon down to big bowls of milk and chunks of bread we

sat to satisfy our present hunger. The long afternoon over a rough prairie

road in a springless heavy waggon had given us large appetites.

Our homely fare disposed of,

we climbed into the lumber waggon and again set forth into the summer's

night. Crossing Buffalo Creek we took the long level plain for Moorehead and

the railroad. Every man in the party tried his turn on John, the driver, to

induce him to trot even a wee bit, but it was no go. John's horses walked,

and continued to walk, and it was not till the early morn of the next day

that we entered the new railway town, just as one of the dance halls was

turning its crowd into the streets. On hearing them Dr. Punshon remarked

drily, that "those young fellows had evidently been to Sunday-school." We

found that the train left at 5 am., and arranging to be called early enough

for a cup of coffee, we lay down for an hour or two to sleep. Here once more

I heard the whistle of a locomotive. Twelve years and better had passed

since I left the northerly railhead at LaCrosse, on the Mississippi.

Steadily northward steam and steel had since then been forcing their way.

Twelve years in the wilderness, but now I am in touch with all the world!

Sharp at five we were away,

speeding behind the iron horse, and to me for a time the sensation was

delightful. "Come with me, John," said Dr. Punshon, and he led the way into

another car and presented me to a company of railway magnates, who soon

satisfied themselves of my "bona-fides," and straightway the questions came

thick and fast concerning, the Canadian North-West. I noticed that it was

extremely gratifying to these men to learn that far north of their line

there were vast areas of fertile country. They thanked me most heartily, and

then pressed Dr. Punshon to come to St. Paul and give them a lecture on his

way home. This he consented to do, and left us at Duluth for St. Paul. At

Brainard we were held up by a subsidence in the road east of us, and after

some hours' waiting were taken to the spot and transferred to another train.

I remember Dr. Punshon was very anxious about this muskeg, and I had to

pilot him across the floating bog at the side of the track. The whole bottom

had fallen out under the dump—indeed it was all dump.

On down the slope of Superior

we rolled, and into the new port of Duluth, where the good ship Cumberland,

with steam up, was awaiting our train. From the hurricane deck of a cayuse

to that of a palatial side-wheeler was a big translation, and for a change I

liked it so long as the lake was placid, and such it proved as we coasted

down the north shore of Lake Superior. We touched at Port Arthur, Nepigon,

and Michipicoten, then on to the "Soo," where I stopped over one boat to

meet some old friends of my boyhood and renew my youth with them among the

scenes of various canoe and Mackinaw boat experiences. I also visited Garden

River, where, with rather and mother and little brother and sisters, we had

landed amongst wild drunken Indians twenty years before. I stood on the spot

where as a lad I had driven the oxen which hauled the timber to build the

first mission house and church. I crossed to Sugar Island and visited the

churches, and found both still alive and active. It was like old times to

hear Mrs. Church exclaim, "Why, Johnnie McDougall !" "Oh, how you talk!"

"You don't say so," etc., etc. Generous and good as neighbors to all of us

they were in those early days.

Coming back to the "Soo," and

while walking on the dock, I met a couple of gentlemen passengers, and at

the first glance knew them to be Hudson's Bay Company officers. A feeling of

gladness came over me as I recognized the stamp of the north and west in

their walk and talk and actions, and soon I was as one of them, though we

had never met previously. I learned in course of an interesting conversation

that they were on their way into the wilds of northern Quebec.

I caught the next boat down

on the Canadian side, and from the deck feasted my eyes on the scenery of

the old North Shore route. Calling in at the Bruce Mines and at Little

Current and Killarney, and crossing the wide stretches of Georgian Bay, we

came into the port of Coiling- wood, where I bade farewell to my Hudson's

Bay Company friends. From Collingwood I took train to Craigvale, where I

expected to find my uncles and cousins, as also other friends. Allandale,

Barrio, Lake Simcoe, all familiar, and it seems but as yesterday when I was

paddling a birch canoe along these shores; and yet more than twelve years of

continuous travel and toil have passed, and many hardships and countless

adventures and perils have been experienced, and the boy has grown to

manhood. "Will my old playmates recognize me?" I ask myself, and as I walk

from the station to uncle's store and home, I am all on the strain in the

excitement of coming home again, and full of the sense that this is indeed

"my own, my native land."

Entering the store I saw my

cousin Charlie waiting on customers, and I stood as one waiting his turn.

People came and vent whom I had known, but I was as a stranger amongst them.

Fully an hour passed and I was not recognized, but after many glances from

Charlie he at last got a glimpse of me as of old, and dropping everything he

exclaimed, "Are you John McDougall?" I nodded ready assent, and then my

welcome was hearty, and presently aunt and other cousins were around me as

one from the dead.

A short sojourn with these

relatives, and then on to Toronto, where I called on my fellow- travellers,

Drs. Punshon and Wood and Mr. Macdonald. I also met the Rev. Lachlan Taylor,

Secretary of Missions, and was gently reminded by both President and General

Secretary that my time in Ontario was short,. They also advised me to look

around for a companion, and indeed were very solicitous on my behalf. A

personal matter, that even my own father had never presuined to mention or

converse with me about, these wise old men were quite insistent upon!

However, I had my own thoughts in the case, and now it came upon me strongly

that I would like to attend college for the year, and immediately I went to

the President, but was met with a prompt refusal. " No, sir," he said, "you

must return; your work needs you. A college education is not an essential,

it is a luxury; neither we nor you can afford it." Thus Dr. Punshon met me

with kindness yet firmness, and though longing for the college, yet my

recent vows of obedience were also ringing in my ears, so I gave up the

matter and settled down to visit and enjoy my short sojourn in eastern

Canada. Nevertheless, Dr. Wood must insist on my visiting one of our

missions where a protégé of his was teaching school; but Providence had

something else in store for me. I found that there would be no boat to this

special point for some days, and therefore took another in an entirely

different direction, and while on this trip met a young lady who made me say

to myself, "If I can win her consent she shall go with me to the

North-West!"

The next time I visited

Toronto Dr. Wood was very anxious to know how I found the people at the

isolated mission, and expressed surprise when I told him I had not been

there. "Well, well," said he, "you must hurry up; the season is advancing

and the distance is great." The Doctor knew a little about it, for he had

gone as far west as Portage la Prairie. Then I told him I was advancing

slowly and wisely from my standpoint, and he said, "Go ahead, young man."

And in good time I did go oil my project and was successful, and late in

September we were married. My bride, poor girl, little thought of the long,

difficult journey on which I was taking her, nor yet, describe as I might,

did she nor many other of the eastern people realize the conditions. But in

her case it was "Will go with you, John, to the ends of the earth if need

be."

We were married at Cape Rich,

and sailed from Collingwood on the Chicora, calling at Owen Sound on the

way. Instead of my bride only I found myself at the head of a little party

bound for the Red River, including portions of two families who expected to

find their complement in the far West. We left Owen Sound some time after

midnight, and soon were out in a gale on the wide stretch of the bay. My

wife proved to be a much better sailor than myself. She and a few others

went to breakfast, while I and the majority had no special desire for

breaking fast. There were some jokes and fun at my expense. One young lady

thought it was great fun that she on her first trip should do better than "a

veteran like Mr. McDougall." I said little, but kept on the broad of my

back. After a time, the ship continuing to roll and pitch, I noticed the

young lady paling a little, and presently she also stretched herself out on

the opposite side of the saloon. Then I opened conversation; it was my turn

to laugh. "So you enjoyed your breakfast?" "Yes," faintly. "You've had a

turn on the deck ?" "Yes," more faintly. "Do you know what they are going to

have for dinner?" "No," in a whisper. "It is now 11.30, are you hungry?"

"No," with pathos and much feeling. All of a sudden my young lady jumped up

and rushed for her stateroom, uttering a distressed "Oh, my! oh, my!" etc.

For the rest of the trip we christened the complaint which affected our

passenger list the " Oh, my!" disease. However, in a few hours we were in

the straits of Killarney, and our agony was over, and not until we reached

Lake Superior was there much chance for further seasickness. Given

comfortable ship and agreeable companions, with weather not too rough, and

the North Shore route is a most enjoyable trip; the scenery is fine, and the

whole run is pleasant.

Locking through the "Soo"

canal, we were soon out on the great Lake Superior and hugging the northern

shore. The weather was propitious, and we kept on deck most of the time. For

the past twelve years my life had been spent on the plains in high

altitudes, and this sniffing of the breeze direct from the fresh waters was

a very much appreciated change. We called, as was the wont at the time, at

every point on the lake, and finally came to Duluth, where we took the train

for the west.

During my stay in the east

the St. Paul, Minneapolis and Manitoba Railway had come north, and, crossing

the Northern Railway east of the Red River, was now advanced as far as the

Red Lake River. Arriving at the latter point, we found to our dismay that

the boat had left oil the afternoon of the previous day with a full load for

Fort Garry. "When would there be another boat?" No one knew. This place in

all truth was "wild and woolly;" gambling and drinking dens and dancing

halls practically made up the town. The rapid building of the railway and

the navigation during the season to this point had brought a full quota of

these parasites of humanity to feed on the navvies and travellers who, when

stranded here, were more or less at their mercy. Obtaining some lunch for my

party in one of the tents, I went out to reconnoitre, and found that it was

twenty miles across the country to Grand Forks, where one might possibly

find some accommodation. I accosted a genuine specimen of the New England

Yankee westernized, and found that he had a waggon and team, which I went to

see, and he offered to drive me over to Grand Forks with my party for twenty

dollars. I told him to hitch up, and then ran to notify my people to be

ready.

In a very short time we were

rolling over the prairie, grateful beyond expression to leave this place of

wild lawlessness. To me the change was delightful. I was again on the

plains, and perched on the top of some luggage, with a couple of children in

hand lest they should jolt off, I thoroughly enjoyed the western air and

scene. We had not gone more than five miles when I saw the smoke-stacks of a

steamer. I watched and waited until I saw she was heading our way, and then

I gave the wild western whoop, and our driver started and wanted to know

where the "Injuns" were. "There are the engines," I said, pointing to the

smoke-stacks, which now and then would appear between the fringing of timber

along the river's bank. "Jerusalem! there she is, sure enough. Well, pardner,"

he continued, "what shall we do?" "Drive over and head her off," was my

answer, and across the prairie we made as rapidly as we could to intercept

the steamer, which had left the railway crossing we had just now come from

more than twenty-four hours since. Such was navigation on this tortuous

stream.

Picking a suitable spot for

the steamer to land at, we waited her appearance, and when she was

sufficiently near I hailed, "Ship ahoy!" "What do you want?" cried the

captain. To go aboard," was my answer. "We are full and have no

accommodation." "Never mind, Captain; shove her bow in and give us a plank,"

I answered. "I tell you we have no room," came back to us. "That is a matter

of detail; take us on board," was my straight answer. Then there was a

change of voice from the same man. "Is that you, Mr. McDougall?" was now the

question. "Yes, Captain," I shouted back, and the bells jingled and the big

wheel spokes rolled over, and right into the bank where we stood came the

nose of the steamer, and in five minutes we with all luggage were on the

boat. The tall Yankee and I split the difference, that is, I gave him ten

dollars and a warm shake of the hand; the bells jingled and over went the

wheel, and we turned to find ourselves in a dense crowd of people seeking

the west country. Every stateroom and berth was occupied, and the saloon

curtained off at night; one part given over to the women and children, and

the balance chalked by the steward so as to give each man his

two-by-six-feet on the floor with one pair of thin blankets. But we were on

the steamer and moving on to the Red, and I was happy to have my party going

to their destination.

On the boat I found Dr. Bryce

and wife, they also newly married and, like ourselves, on the homeward

journey. I also found on this much crowded steamer Commodore Kitson, the

manager of the line, a typical old frontiersman. This was the beginning of

the rush to Manitoba —the name there usually pronounced with a marked accent

on the last syllable. The new country was now attracting some attention. It

was three days from the time we boarded the steamer before we rounded the

point into the Red, and the boat was actually four days making the run from

the Crossing, a distance of only twenty miles across the country. Now we

were out on the larger Red River and would make better time.

Reaching Grand Forks, I saw

Mr. Kitson with his private secretary debark, and then there was a rush to

the steward to secure the vacated stateroom, but the answer was uniform,

"Already engaged," and in due time the steward came to me and said that Mr.

Kitson had instructed him to keep the room for Mr. McDougall. I had not

asked for it, yet here was a case of the last being first, and we were

thankful for the kindly act of the old pioneer. However, I did not approach

that stateroom for some time, as there were many who thought they had a

prior claim to it.

Down the "Red River of the

North" we headed with our steamer, the International Captain Amyot in

command, laden with many tons of freight and crowded from the main to the

hurricane deck with men and women seeking their fortune in this great free

country. They were of all classes—professional, agricultural,

mechanical—tradesmen of all sorts; also some of no particular occupation,

nondescripts, who had come to the West thinking that perhaps this new

strange land might locate them, for thus far in life they had found it

impossible to locate themselves. A queer medley of nationalities they were;

many of them Scotch, among whom the Professor (Dr. Bryce) took the lead,

which, by the way, he has kept well, for he is now, as I write, the honored

Moderator of the General Assembly of the great Presbyterian Church in

Canada, and, I believe, making his calling and election sure for the greater

General Assembly of the first-born in the larger kingdom.

The last time I went down

this muddy stream we were on a small barge, and our motive power big sweeps

in the hands of stalwart men whose loins were girt about with Hudson's Bay

sashes, and whose meat was pemmican. Four at a time, in six-hour turns,

these men kept at it day and night without stop, and for eight days and

nights we wound down from Georgetown, a city of two houses, even to Fort

Garry and the Red River Settlement, of whose people and their habit of life

a facetious Yankee said some years later, "Why, sir, everything is done out

here by man's strength and stupidness," for as yet no modern machinery had

come in, neither had it entered into the heads or hearts of any of these

passive aboriginal peoples to dream of such. But now we are vibrant with the

throb of our engines; every plank and bolt in our vessel is nervous with

motion, and undoubtedly as we swing the bends of the river we are conscious

of the beginning of a wonderful change. In this we have the advantage of our

fellow- passengers, for we have some knowledge of the country to be

exploited, and in a small way its infinite possibilities are dawning upon

us.

It was a beautiful Sabbath

morning as we "crossed the Rubicon "--to wit, the forty-ninth parallel—and

entered into our own domain. Dr. Bryce preached, while I acted as precentor

and general " roustabout," and our service was well attended and much

appreciated. It was well on in the afternoon that we began to touch the

outer fringings of the old half-breed settlements. A crowd of new-corners

were around me, and I was hurt to hear their language as they spoke of the

English and Scotch and German and French mixed bloods and Indian peoples.

These very "fresh" men were nasty and vulgar, and sometimes most shameful in

their modes of expression. Presently I had my chance, for as we swept past a

cluster of houses ranged in a row on the bank, a typical French half-breed

in plains' costume came out of one house and entered another, and the crowd,

as they noticed his flaxen hair and beard and clear white face, exclaimed:

"There is a white man; he is no d—d breed, at any rate." Then I said "There

is just where you are mistaken, gentlemen, for that is a genuine mixed

blood, and many of these are as white and as fair as yourselves; and in any

case, why call them such names and use such nasty language towards them?

Whose fault is it, if it is any fault? Where did the Scotch and English and

French come from? In all this you are belying yourselves, gentlemen, and I

must say that I have felt hurt as I have mingled with you and listened to

the tone of your conversation concerning these people. You are going into

their country and will have more or less intercourse with them, and I advise

you to be more careful, or at least be more courteous," and as I turned on

my heel I added casually, "for I also am a half- breed." Later one of the

party came to inc curious to know if I really meant what I said. it I really

a half-breed?" I laughingly told him that my mother was a pure-bred

Englishwoman and my father a Scotch-Canadian, so I thought very reasonably

that I was a half- breed. I have knocked about a lot and have been thrown

into association with many peoples, but for sublime indifference to the

sensibilities of other folk and the most flagrant selfishness the ordinary

white man "takes the cake," and were it not for the leaven of Christianity

we would be at war with all the rest of mankind. |