|

WITH the first approach of

winter, the majority of the Indians re-crossed the Saskatchewan and pitched

southward for buffalo. Some waited until the ice-bridge was formed, and a

few went northward into the woods to trap and hunt for fur; but it rarely

happened that there were no Indians about the place. Strangers, having heard

that missionaries were settling on the river near the "Hairy Bag," (which

was the old name for a valley just back of the mission house, given to it

because it had been a favorite feeding-ground for buffalo) would come out of

their way to camp for a day or two beside the new mission, and see for

themselves what was going on and what was the purpose of such effort. Many a

seed of truth found lodgment in the hearth of these wanderers, to bear rich

fruit in soul-winfling in later days.

Then the missionary became

noted as a "medicine man," able to help the divers diseased. Many of these

were brought from afar that they might reap the benefit of his care. Then

all the hungry and naked hunters, those out of luck, upon whom some spell

had been cast (as they believed) so that their nets failed to catch, their

guns missed fire, and their traps snapped, or their dead-falls fell without

trapping anything—where else should these unfortunates go- for help and

advice and comfort but to the CC praying man." And thus with our large

party, and the very many other calls upon our commissariat, it kept some of

us on the jump to gather provisions sufficient to "keep the pot boiling."

Already, because of the snow

coming earlier, we had hauled most of our fish from the lake, fairly rushing

things after we had the road broken. Generally two trips were made in three

days, and now and then a trip a day. Away at two or three o'clock in the

morning; forty miles out light, then lashing a hundred or more frozen

whitefish on our narrow dog-sled, and home again the same evening with the

load, yoked to hardy dogs and still hardier men. One such trip was enough

for any weakling or faint-heart who might try it.

Owing to the great demands

upon our larder, already referred to, early in December of this winter

(1863) we found our supply of fresh meat nearly exhausted, and so determined

to go out in search of a fresh supply. Already a good foot of snow was on

the ground around Victoria, and there was more south and ease, where the

Indians and buffalo were, but this did not stop us from starting out. The

party consisted of father, Peter, Tom, a man named Johnson, and myself. We

took both horses and dogs. The second day out we encountered intensely cold

weather, and this decided us to strike eastward into the hills along the

south of the chain of lakes. The third day we killed two bulls, and as the

meat was very good, father told Tom and I to load our sleds and return to

the mission, and to come right back again.

Off we started with our

loads, but as we had a road to break across country our progress was slow.

We had no snowshoes, and I had to wade ahead of the dogs, while Tom brought

up the rear. That night was one of the coldest in my experience, and I know

what cold means if any man does. Tom and I had each a small blanket. We made

as good a camp as we could by clearing away the snow and putting down a lot

of frozen willows. We kept up a good fire, but the heat did not seem to have

any radiating power that night—an almost infinite wall of frosty atmosphere

was pressing in on us from all sides. Putting our unlined capotes beneath

and the two blankets over us, we tried to sleep, for we had travelled

steadily and worked hard all the day. I went to sleep, but Tom shivered

beside me, and presently woke me up by exclaiming: "John, for God's sake

make a fire! I am freezing!" I hurried as fast as I could, and soon had a

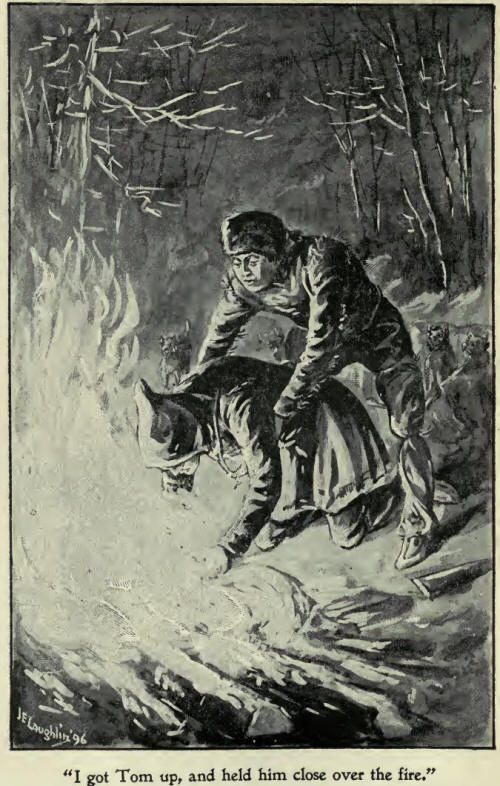

big blaze going. Then I got Tom up and held him close over the fire, rubbing

and chafing, and turning him all the while, until the poor fellow was

somewhat restored. Looking gratefully at me, he then noticed that I had

neither coat nor mitts on. I had not felt the need of these, so startled and

anxious was I because of my comrade's condition. We did not try to sleep any

more that night, but busied ourselves in chopping and carrying logs for our

fire, and religiously keeping this up.

With the first glimmer of day

we were away, and steadily kept our weary wading through the deep, loose

snow. About eight in the evening we came out on the trail leading to the

mission, and would have been home by midnight, only that I had to make

another fire about ten o'clock, and give Tom another thawing out to save his

life. He was a slight, slim fellow, and the hitter cold seemed to go right

through him; but he was a lad of real grit and true pluck.

Fortunately for Tom and I, it

was between two and three o'clock Sunday morning when we reached the

mission. This gave us the day's rest, otherwise we would have felt in duty

bound to turn right around and go back to our party. Our people at home were

glad to have the fresh meat, and though Mr. Woolsey had then spent eight

years among the buffalo, he pronounced it "good cow's meat." We concluded

thereupon that at any rate it was extra good "bull's meat," and were

satisfied with our part of the work.

A little after midnight Tom

and I set forth on our return. The cold was intense, but we were light, and

running and riding we made a tremendous day of it, coming about noon to

where we had parted from our friends. Following. them up we came to where

they had found the trail of an Indian camp, and gone on it. Carrying on, we

camped when night came, and as we had now a distinct trail, we left our camp

in the night, and a little after daylight had the satisfaction of seeing the

white smoke from many lodges rising high into the cold, clear air in the

distance. This stimulated us, and within two tours we were in the camp and

again with our friends. They had fallen in with a party of Indians from

Whitefish Lake and north of it, and father and party were now in Chief

Child's lodge. Both missionary and people had been having a good time

together. These simple people, having been reached by the Gospel, and having

accepted the truth, were never happier than when receiving an unexpected

visit from a missionary. When the missionary delighted in his work and made

himself as interesting as possible to the people, and spared no pains to

make his visit profitable and educative, as father always did, then their

satisfaction knew no bounds. With their teacher they all became optimistic,

hopeful, and joyous.

Father told me that Chief

Child, our host, had given him some of the finest meat he had ever eaten,

and that our hostess knew how to cook buffalo meat to perfection. Now, as in

my experience amongst buffalo-eating Indians was one year older than

father's, I began to suspect that he had been caught napping, and had eaten

what he would not have indulged in had he known; so I quietly enquired of

Chief Child what he had fed father on. He replied, "We have no variety. He

has had nothing but buffalo meat in my tent;" then, as if correcting

himself, he added, "Perhaps it was the unborn calf meat he found so good."

Just as I thought, said I to myself; now I have a good one on father! Later

on, when he repeatedly spoke of Chief Child's hospitality, I mentioned this,

and father opened his eyes, then quite philosophically said, "Can't help

it—it was delicious anyway."

Father and party were about

ready to start back when we reached the camp, having secured fine loads of

both fresh and dried meats, so we loaded up and started for home. As we with

the dog-trains could travel faster, and make longer distances than the

horses, Peter and Tom and I went on, leaving lather and Johnson to come as

they could. We were home, and had made another trip to the fishery and back,

by the time they got in with their loads.

Mr. Woolsey was now ready to

set out on the missionary tour to Edmonton, usually taken during the

holidays. It had become an established custom for the officers and employees

of the Hudson's Bay Company who desired to come to Edmonton on business or

pleasure to do so at that time, and the missionary had then the opportunity

of meeting people from the outposts as well as those resident in the Fort.

In accord with this purpose

we left Victoria in time to reach Edmonton the day before Christmas. I drove

the cariole as usual, and we had with us a newcomer, one "Billy" Smith, a

man we had known at Norway House, and who had now, somehow or other, drifted

into this upper country. Billy drove the baggage and "grub train."

Simultaneous with our starting for Edmonton, father, Peter and the others

also set out to procure, if possible, another load of meat, as there was no

telling where the buffalo might be driven to in a short time.

We went by the south side,

taking the route I had followed on my lone trip, and arrived at Edmonton on

time. Remaining there during the holiday week, we started back the day after

New Year's. While we were there a small party of Mountain Stoneys came in on

a trade to the Fort. With these was Jonas, one of Rundle's converts, who

understood Cree well, and Mr. Woolsey arranged wii him to return with us to

Victoria, as father and he were very desirous of securing the translation of

some hymns into Stoney. Thus our party was augmented by Jonas and a

companion. The rest of this small party of Stoneys, on their return trip

south, were attacked by the Blackfeet when about fifty miles from the Fort,

and several were killed and wounded on both sides; but the Stoneys, though

much outnumbered, eventually succeeded in driving their enemies away. It may

be that Jonas saved his life that time by coming with our company.

Just as we were starting from

Edmonton, Billy Smith was bitten in the hand by one of the dogs. The wound

became very bad almost immediately, and grew worse as we proceeded. The

weather was now very cold, and I had a lively time with a helpless man in my

cariole, and another, almost as helpless, behind with the baggage train.

When the Indians came up to camp they helped me, but they were generally a

long way in the rear.

I shall never forget a scare

Mr. Woolsey gave me on that trip. It was the next morning after leaving

Edmonton. We had started early in the night, and I was running behind the

cariole, holding the lines by which I kept it from upsetting. We had left

the others far in the rear. Mr. Woolsey was fast asleep; myself and dogs

were quietly pursuing the narrow trail, fringed here by dark rows of

willows. The solitude was sublime. Suddenly from the earth beneath me, as it

seemed, there came, unearthly in its sound, a most terrible cry. I dropped

the line and leaped over a bunch of willows, feeling my cap lifting with the

upward motion of my hair. My pulse almost ceased to beat. Then it flashed

upon me it was Mr. Woolsey having the "nightmare." I was vexed with myself

for being so startled, and vexed with him for committing so horrible a thing

under such circumstances, and I have to confess it was no small shake that I

gave that cariole, saying at the same time to Mr. Woolsey as he awoke,

"Don't you do that again!" As he was feeling chilled I suggested that he

alight and walk a bit, while I dashed on to make a fire; all of which we

did, I having a big blazing fire on when Mr. Woolsey came up. I melted snow

and boiled the kettle, and we had our second breakfast, though it was still

a long time till daylight. The Indians did not come up at this spell, so we

left some provisions beside the fire and went on. That was a very hard trip

on all of us. Mr. Woolsey, wrap him as I would, seemed likely to freeze to

death every little while. Smith's hand was growing worse, and he was in

intense pain with it. I was in sore trouble with my passenger and my

patient. Sometimes I had to roll Mr. Woolsey out of the cariole in order to

get him on his feet and beside the fire. At times the condition of things

was ludicrous in the extreme.

Before daylight the second

morning—for we were two nights on the way—I was a long distance ahead of

Billy, and was becoming anxious about him. I knew Mr. Woolsey was cold, so I

stopped in the lee of a bluff of timber, and making a big fire put down some

brush, and then pulled the cariole up to this, and half lifted, half rolled

Mr. Woolsey out beside the fire, and finally got him on his feet. Then I

turned to get the kettle, for I had taken this and the axe and some food

from Bill's provision sled because he was always so far behind. Just then I

smelled something burning, and there was Mr. Woolsey standing over the fire,

fairly smoking. His coat sleeves were singed, and when he sat down his

trousers burst asunder at the knees, and the rent almost reached from the

bottom hem to the waist band.

We both laughed heartily. I

could not help it, but Mr. Woolsey's "unmentionables" were certainly past

mending. By-and-bye we came out upon our own provision trail, and I saw that

father and party had passed on the day before; and now as we would make good

time from this in to the mission, only twelve miles distant, I felt like

waiting for Bill, so I said to Mr. Woolsey, "You had better walk on and warm

up while I wait for our man, as the poor fellow wants all the encouragement

he can get." With much bracing and lifting I got Mr. Woolsey to his feet,

and expecting him to start on, busied myself with my dogs; when presently,

looking up, I saw him walking out on the road to the plains. I shouted to

him, "Where are you going?" And he answered back, "I am going homeward." I

told him he was wrong, but he was stubborn in the thought that he was right,

and I had to run after him, and fairly turn him around, and show him the

track made by father and his party homewards, before I could convince him

lie was wrong. This was now his ninth winter in the West, and still his

organ of locality was so defective that he would lose himself in a ten-acre

field. Kind, noble, good man that he was, yet it was impossible for him to

adapt himself to a new country. He would always be dependent on others.

When Smith did come up, I

encouraged him, telling him to pluck up—only twelve miles, and a passable

road at that, then home, and nursing for him. Then I dashed after Mr.

Woolsey, tucked him into the cariole, and in a short time was at the top of

the very steep hill opposite the mission. Here I was in another box. I dare

not go down with Mr. Woolsey in the cariole, yet the dogs saw home and were

eager to jump over the brow, and dash down the precipice. I held them back,

and called to my passenger to get out, which he essayed to do but could not.

There was a coulee on one side of the road, and a brilliant idea struck .me.

Deciding to bring the force of gravity to aid me in my dilemma, I upset the

cariole on to the side of the coulee. Out rolled Mr. Woolsey, and he kept on

rolling until he reached the bottom of the gully. This suppled him somewhat,

and now, with the sides of the gully to help him, he rose to his feet. I

waited to see him stand, and then, almost weak with internal mirth, for I

did not want him to see me laughing, I followed my dogs over the hill and

drove on to the house. After unharnessing my dogs, I went back to meet poor

Billy, and help him down the hill.

Many a laugh Mr. Woolsey and

I had afterwards over that trip, though at the time there were occasions

when things looked serious. Poor Billy Smith had a terrible time with his

hand. Inflammation set in, mortification threatened, and some of our party

had to work day and night to save him. Jonas and his companion came in some

hours after us, and for several days Peter and Jonas worked on the

translation of some hymns into the Stoney language. Then Jonas, with such

help as father and Mr. Woolsey could give him, and with a copy of these

hymns in the syllabic characters in his bosom, set out on his three hundred

mile tramp to his mountain home. Fortunately he missed any such mishap as

that which his friends encountered on their return home, and reached his

people in good time, and was able to teach others these Gospel hymns, for

which he had travelled so far in the intense cold of a Northern winter. |