|

FATHER had been much

disappointed at not seeing the Mountain Stoneys on his previous trip west,

as time did not permit of his going any farther than Edmonton; but now with

temporary house finished, hay made, and other work well on, and as it was

still too early to strike for the fresh meat hunt, he determined, with Peter

as guide, to make a trip into the Stoney Indian country. Mr. Woolsey's

descriptions of his visits to these children of the mountains and forests,

of their manly pluck, and the many traits that distinguished them from the

other Indians, had made father very anxious to visit them and see what could

be done for their present and future good.

Accordingly, one Friday

morning early in September, father, Peter and I left the new mission, and

taking the bridle trail on the north side, began our journey in search of

the Stoneys. We had hardly started when an autumn rainstorm set in, and as

our path often led through thick woods, we were soon well soaked and were

glad to stop at noon and make a fire to warm and dry ourselves. Continuing

our journey, about the middle of the afternoon we came upon a solitary

Indian in a dense forest warming himself over a fire, for the rain was cold

and had the chill of winter in it.

This Indian proved to be a

Plain Cree from Fort Pitt, on the trail of another man who had stolen his

wife. He }ad tracked the guilty pair up the south side to Edmonton, and

found that they had gone eastward from there. I told him that a couple had

come to Victoria the day before, and he very significantly pointed to his

gun and said: "I have that' for the man you saw." We left him still warming

himself over his fire, and, pushing on, reached Edmonton Saturday evening.

Father held two services on Sunday in the officers' mess-room, both well

attended.

Monday morning we swam our

horses across the Saskatchewan, and crossing ourselves in a small skiff,

saddled and packed up, and struck south on what was termed the Blackfoot

Trail." Within ten minutes from leaving the bank of the river we were in a

country entirely new to both father and me. We passed Drunken Lake, which

Peter told us had been the usual camping- ground of the large trading

parties of Indians who periodically came to Edmonton. They would send into

the Fort to apprise the officer In charge of their coming to trade. He would

then send out to them rum and tobacco, upon which followed a big carousal;

then, when through trading, being supplied with more rum, they would come

out to this spot, and again go on a big drunk, during which many stabbing

and killing scenes were enacted. Thus this lake, on the sloping shores of

which these disgraceful orgies had gone on for so long, came to be called

Drunken Lake. Fortunately at the time we passed there the Hudson's Bay

Company had already given up the liquor traffic in this country among

Indians. We passed the spot where Mr. Woolsey and Peter had been held up by

a party of Blackfoot, and where for a time things looked very squally, until

finally better feelings predominated and the wild fellows concluded to let

the "God white man" go with his life and property.

Early in the second day from

Edmonton, we left the Blackfoot trail, and started across country, our

course being due south. That night we camped at the extreme point of Bear's

Hill, and the next evening found us at the Red Deer, near the present

crossing, where we found the first signs of Stoneys. The Stoneys made an

entirely different trail from that of the Plain Indians. The latter left a

broad road because of the travois on both dogs and horses, and because of

their dragging their lodge poles with them wherever they went. The Stoneys

had neither lodge poles nor travois, and generally kept in single file, thus

making a small, narrow trail, sometimes, according to the nature of the

ground, very difficult to trace.

The signs we found indicated

that these Indians had gone up the north side of the Red Deer River, so we

concluded to follow them, which we did, through a densely wooded country,

until they again turned to the river, and crossing it made eastward into a

range of hills which stretches from the 'Red Deer south. In vain we came to

camping places one after another. The Indians were gone, and the tracks did

not seem to freshen. It was late in the afternoon that the trail brought us

down into the canyon of the Red Deer, perhaps twenty miles east of where the

railroad now crosses this river. The banks were high, and in some places the

view was magnificent. In the long ages past, the then mighty river had burst

its way through these hills, and had in time worn its course down to the

bed-rock, and in doing so left valleys and flats and canyons to mark its

work. In the evolution of things these had become grown over with rich grass

and forest timber, and now as we looked, the foliage was changing color, and

power and majesty and beauty were before us.

Presently we were at the foot

of the long hill, or rather series of hills, and found ourselves on the

beach of the river. Peter at once went to try the ford. Father and I sat on

our horses side by side, watching him as he struck the current of the

stream. Flocks of ducks were flying up and down temptingly near, so father

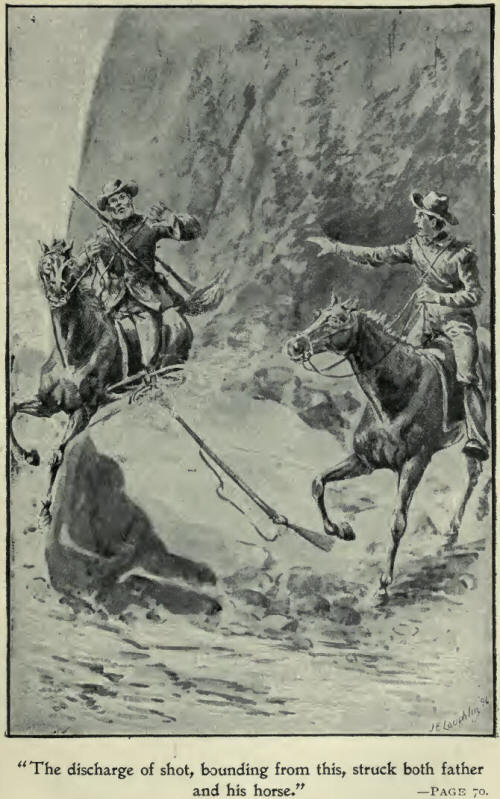

shot at them as he sat on horse-back. I attempted to do the same, but the

cap of my gun snapped. I was about to put on another cap when my horse

jerked his head down suddenly, and as I had both bridle-lines and gun in the

one hand, he jerked them out, and my gun fell on the stones, and, hitting

the clog-head, went off- As there was a big rock between my horse and

father's, slanting upwards, the discharge of shot bounding from this struck

both father and his horse.

You have hit me, my son!"

cried my father.

"Where?" I asked anxiously,

as I sprang from my horse to my father's side, and as he pointed to his

breast, I tore his shirt open, and saw that several pellets had entered his

breast.

"Are you hit anywhere else?"

I asked; and then he began to feel pain in his leg, and turning up his

trousers I found that a number of shot had lodged around the bone in the

fleshy part of his leg below the knee.

In the meantime the horse he

was riding seemed as if he would bleed to death. His whole breast was like a

sieve, and the blood poured in streams from him. Peter saw that something

was up and came on the jump through the rapid current, and we bound up

father's wounds, turned his horse loose to die—as we thought—and then

saddling up another horse for father we crossed the river in order to secure

a better place to camp than where we then were. To our astonishment, the

horse followed us across, and went to feeding as though nothing had

happened.

We at once set to work taking

out the pellets of shot. This was of a large size and made quite a wound. We

took all out of his chest, and some from his leg, but the rest we could not

extract, and father carried them for the rest of his life. We bandaged him

with cold water and kept at this, more or less, all next day.

During the intervals of

waiting on father, we burned out our frying-pan, and prospected for gold. We

found quite a quantity of colors, but as this was a dangerous country, it

being the theatre of constant tribal war, a small party would not be safe to

work here very long; so it will be some time before this gold is• washed

out.

No one can tell how thankful

I was that the accident was not worse. The gun was mine; the fault, if any

there were, was mine. With mingled feelings of sorrow and gladness, I passed

the long hours of that first night after the accident. Father was in great

pain at times, but cold water was our remedy, and by the morning of the

second day we moved camp out of the canyon up to near the mouth of the Blind

Man's River.

The next morning we were up

early, and while I brought the horses in, father and Peter had determined

our course. I modestly enquired where we were going, and they told me their

plan was to come out at a place on our outbound trail, which we had named

Goose Lakes, because of having dined on goose at that place. I ventured to

give my opinion that the course they pointed out would not take us there,

but in an altogether different direction. However, as it turned out, Peter

was astray that morning, and got turned around, as will sometimes happen

with the best of guides. After travelling for some time in the wrong

direction, as we were about to enter a range of thickly-wooded hills, the

brush of which hurt father very much, I ventured to again suggest we were

out of our way. Peter then acknowledged he was temporarily "rattled," and

asked me to go ahead, which I did, retracing our track out of the timber,

and then striking straight for the Goose Lakes, where we came out upon our

own trail about noon. After that both father and Peter began to appreciate

my pioneering instincts as not formerly.

Most of this time we had been

living on our guns. In starting we had a small quantity of flour, about two

pounds of which was now left in the little sack in which we carried it.

Saturday afternoon we crossed

Battle River, and arranging to camp at the "Leavings," that is, at a point

where the trail which in after years was made between Edmonton and Southern

Alberta, touched and left the Battle River, Peter followed down the river to

look for game, while father and I went straight to the place where we

intended to camp. Our intention was to not travel on Sunday, if we could in

the meantime obtain a supply of food. Reaching this place, father said to

me, "Never mind the horses, but start at once and see what you can do for

our larder." I exchanged guns with father, as his was a double barrel and

mine a single, and ran off to the river, where I saw a fine flock of stock

ducks. Firing into them, I brought down two. Almost immediately I heard the

report of a gun away down the river, and father called to me, "Did you hear

that?" I said "Yes." Then he said, "Fire off the second barrel in answer,"

which I did, and there came over the hill the sound of another shot. Then we

knew that people were near, but who they were was the question which

interested us very much. By this time I had my gun loaded, and the ducks got

out of the river, and had run back to father. Peter came up greatly excited,

asking us if we had heard the shots. We explained that two came from us, and

the others from parties as yet unknown to us. "Then," said he, "we will tie

our horses, and be ready for either friends or foes."

Presently we were hailed from

the other bank of the river, and looking over we saw, peering from out the

bush, two Indians, who proved to be Stoneys. When Peter told them who we

were, there was mutual joy, and they at once plunged into the river, and

came across to us. Their camp, they informed us, was near, and when we told

them we were camped for Sunday, they said they would go back and bring up

their lodges and people to where we were. They told us, moreover, that there

were plenty of provisions in their camp, that they had been fortunate in

killing several elk and deer very recently—all of which we were delighted to

hear.

If these had been the days of

the "kodak," I would have delighted in catching the picture of those young

Indians as they stood before us, exactly fitting into the scene which in its

immensity and isolation lay all around us. Both were fine looking men. Their

long black hair, in two neat braids, hung pendant down their breasts. The

middle tuft was tied up off the forehead by small strings of ermine skin.

Their necks were encircled with a string of beads, with a sea-shell

immediately under the chin. A small thin, neatly made and neatly fitting

leather shirt, reaching a little below the waist; a breech cloth, fringed

leather leggings, and moccasins, would make up the costume; but these were

now thrown over their shoulders as they crossed the river. Strong and

well-built, with immense muscular development in the lower limbs, showing

that they spent most of the time on their feet, and had climbed many a

mountain and hill, as they stood there with their animated and joyous faces

fairly beaming with satisfaction because of this 'glad meeting, and that the

missionary and his party were going to stay some time with them and their

people, they looked true specimens of the aboriginal man, and almost, or

altogether (it seemed to me) just where the Great Spirit intended them to

be. I could not help but think of the fearful strain, the terrible wrenching

out of the very roots of being of the old life, Were must take place before

these men would become what the world calls civilized.

Away bounded our visitors,

and in a very short time our camp was a busy scene. Men, women, and

children, dogs and horses! We were no more isolate and alone. Provisions

poured in on us, and our commissariat was secure for that trip. To hold

meetings, to ask and answer questions, to sit up late around the open

camp-fire in the business of the Master, to get up early Sunday morning and

hold services and catechize and instruct all the day until bedtime again

came, was the constant occupation and joy of the missionary, and no man I

ever travelled with seemed to enter into such work and be better fitted for

it than my father. Though he never attempted to speak in the language of the

Indian, yet few men knew how to use an interpreter as he did, and Peter was

then and is now no ordinary interpreter.

These Indians told us that

the Mountain Stoneys were away south at the time, and that there would be no

chance of our seeing them on the trip; that in all probability they would

see the Mountain Indians during the coming winter, and would gladly carry to

them any messages father might have to send. Father told them to tell their

people that (God willing) he would visit their camps next summer; that they

might be gathered and on the look-out for himself and party sometime during

the "Egg Moon." He discussed with them the best site for a mission, if one

should be established for them and their people. There being two classes of

Stoneys, the Mountain and the Wood, it was desirable to have the location

central. The oldest man in the party suggested Battle River Lake, the head

of the stream on which we were encamped, and father determined to take this

man as guide and explore the lake.

Monday morning found us early

away, after public prayer with the camp, to follow up the river to its

source. Thomas, our guide for the trip to the lake, was one of those men who

are instinctively religious. He had listened to the first missionary with

profound interest, and presently, ending in this new faith that which

satisfied his hungry soul, embraced it with all his heart. Thus we found him

in his camp when first we met, and thus I have always found the faithful

fellow, during thirty-two years of intimate knowledge and acquaintance with

him.

We saw the lake, and stood on

the spot where some of Rundle's neophytes were slaughtered by their enemies.

This bloody act had nipped in the bud the attempt of Benjamin Sinclair,

under Mr. Rundle, to establish a mission on the shore of Pigeon Lake, only

some ten miles from the scene of the massacre, and drove Ben and his party

over two hundred miles farther into the northern country. We were three days

of steady travelling on this side trip, and reached our camp late the

evening of the third day.

Two more services with this

interesting people, and bidding them good-bye, we started for home by a

different route from that by which we had come. Going down Battle River, we

passed outside the Beaver Hills, skirted Beaver Lake, and passing through

great herds of buffalo without firing a shot—because we had provisions given

us by the Indians—we found ourselves, at dusk Saturday night, about

thirty-five miles from Victoria. Continuing our journey until after

midnight, we unsaddled, and waited for the Sabbath morning light to go on

into the mission.

Early in the morning, as we

were now about ten miles from home, we came upon a solitary lodge, and found

there, with his family, "Old Stephen," another of the early converts of our

missionaries. I had often heard Mr. Woolsey speak of the old man, but had

never met him before. As he stood in the door of his tent, leaning on his

staff, with his long white hair floating in the breeze, he looked a

patriarch indeed. We alighted from our horses, and after singing a hymn

father led in prayer. Old Stephen was profoundly affected at meeting with

father. He welcomed him to the plains and the big Saskatchewan country, and

prayed that his coming might result in great good.

As we were mounting our

horses to leave him, the old man said: "Yes, with you it is different; you

have God's Word, can read it, and understand it. I cannot read, nor do I

understand very much, but I am told that God said, 'Keep the praying day

holy,' and, therefore, wherever the evening of the day before the praying

day finds me, I camp until the light of the day after the praying day

comes," and fully appreciating the old man's consistency, we also could not

help but feel rebuked, though we were in time for morning service at the

mission, and home again once more. |