WHO THE EARLY SETTLERS WERE—THE UNITED EMPIRE LOYALISTS—BUTLER'S

RANGERS—THE MENNONITES AND TUNKERN.

A

LARGE

proportion of the people who

settled on the frontier of Canada during the earlier days of settlement were

United Empire Loyalists, those

who came from the neighboring States of the American

Union at the

close of the Revolutionary War of 1776.

The first settlement of any

note was that made at Adolphustown, on the Bay of Quinte, in June,

1784. After

that date, settlements grew up on the St. Lawrence

Niagara and Detroit Rivers, and at Long Point, on Lake

Erie. The

impression is general that there were but a few

squatters previous to

that time. Provincial Government

affairs, however, being at that period

in an unorganized

condition, such records as are at hand have only the

reliability of tradition. A number of the first settlers were persons who

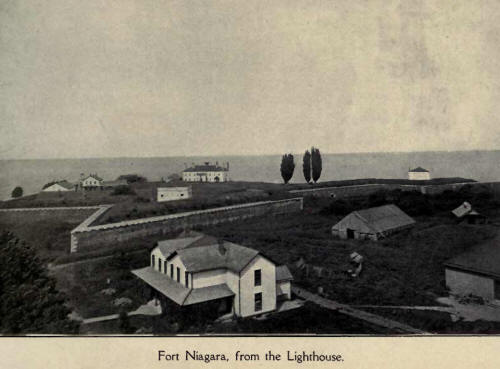

had naturally sought refuge in the vicinity of Fort Niagara and other

border forts, then in the possession of England, from the relentless

persecution that was waged against British sympathizers intending to

return home when peace was concluded, as they fully expected it would be,

in favor of Britain; but, finding the result to be contrary to their

expectations, they crossed the border and took up land on the Canadian

side. Colonel Butler and his Rangers were granted a large tract of land in

the vicinity of what is now the town of Niagara.

The first settlers were a mixed stock of English, Irish, Scotch and

German, many of whose ancestors had settled in the United States, then

British territory, a century or more previous, some of them probably

coming to America on the Mayflower, in 1620. This class of settlers, who

came mostly from New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania, brought with them

the customs, habits and style of living of their American forefathers.

Being of a Conservative type, they preferred a monarchical to a republican

form of government. After these settlers came a large number of Yankees,

attracted by the fertile lands of Canada; and, although they were not

British in sentiment, many of them afterwards became loyal subjects of the

country, and fought for Britain in the War of 1812. There were whole

settlements of "Pennsylvania Dutch" (properly called German), adherents of

the Mennonite and Tunker faiths, whose descendants to this day make up a

large part of the population of Welland, Lincoln, Waterloo and York

Counties. There were also large settlements of Quakers, particularly in

the vicinity of Font Hill, near St. Catharines, and along the Bay of

Quinte, who, like the Mennonites, left the States, fearing the Government

might insist on their bearing arms. The feeling against British

sympathizers being so strong, there was some talk of compelling all,

irrespective of their religious belief, to take part in military affairs.

Many of the Mennonites and Quakers, having been granted the religious

freedom they desired under British rule, were not in sympathy with the

Revolutionary party. This brought down the wrath of the new Government

upon them, and, although they threatened to enact measures that would

curtail the freedom of these sects, they never carried their threats into

execution. There were also a few settlers from the British Isles and from

Germany, but the larger number of this class came later on. Many of the

British soldiers who had taken part in the Revolutionary War and the War

of 1812, having been given free grants of land by the Government, after

receiving their discharge, settled in the country.

The United Empire Loyalists.

If honor is a mark of nobility, then the old United

Empire Loyalists can truly be classed among the first aristocracy of

Canada, for a more honorable class of people

never settled in the Province. Steadfast in character, true to their

principles, loyal to their king, they chose to leave their homes and

property in the United States and come and hew out new homes for

themselves in the Canadian backwoods rather than remain under a government

so antagonistic and bitter towards the Mother Country they loved. Many of

them had considerable property, but they preferred to sacrifice it all

rather than become citizens of a hostile government. To be sure the

British Government gave them grants of land, and furnished many things

necessary for begin- fling life in a new country so far away from the

older settled parts; still it did not begin to repay them for the

hardships and privations they endured in the early days of their

settlement. Many of them sundered family ties that they might remain true

to their convictions and allegiance. As an instance, the writer has in

mind one family where the mother remained in Pennsylvania with several of

her children, while the father came to Canada with the remaining two, and

although the mother followed the waggon conveying her husband and children

away, weeping, and trying to prevail on them to remain,

it was of no avail. Possibly he had good reasons for leaving the country;

for the Whigs had burned his house, and all there was in it, because he

sympathized with the Royalist party.

A sequel to the above took place

several summers ago, when a party of the descendants of the Pennsylvania

branch of the family visited their Canadian cousins, exchanging fraternal

greetings, renewing acquaintance, and endeavoring to perpetuate the love

and friendship existing between the two branches of the family which,

though differing in nationality, are yet one in blood.

Mr. Kirby, in his "Annals of

Niagara," says that "every one of the U. E. Loyalists had a military

bearing, an air of dignity, and a kindly spirit of comradeship, derived

from dangers and hardships which they had shared together." The wealth and

aristocracy of the Colonies, as a rule, were arrayed on the side of the

Royalist party, while many of the rebels were persons having no great

interest at stake. The defeat of their party meant no great loss to them,

while on the other side it meant the loss of all, especially if they had

been active partisans, or were not willing to swear allegiance to the new

government. Can we wonder at the staunch conservative principles of their

children and grandchildren who were our parents? To this adherence to the

principles of monarchical government, as an American author has said, "was

due the sterling character and dignity of these people." They believed in

a principle and they fought for it. The old U. E. Loyalists never got over

their bitterness towards the United States. This antagonism was inherited

by their descendants for several generations. It was more of a national

than an individual hatred, however. The women were equally as patriotic

and loyal as the men, and you could not offend one of them more than by

saying anything against their country. It is told of one of the women in

the early days that she would not eat at the same table with a Yankee. Her

reason for being so bitter was that her husband had been shot in cold

blood by the rebels during the Revolutionary War. Many of these women

displayed their patriotism and loyalty during the war of 1812 by looking

after the crops while their husbands were away fighting for their country.

The firmness and dignity of the

old U. E. Loyalists and their descendants were due to a great extent, no

doubt, to their military training, for in the fore part of the nineteenth

century all men between a certain age were enrolled in the militia.

Butler's Rangers.

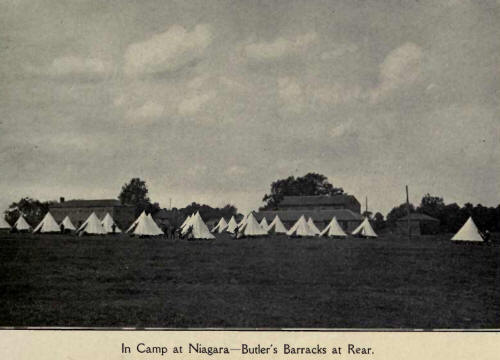

Many of the United Empire

Loyalists were military men who had taken part in the Revolutionary War. A

large number of those who settled in the vicinity of Niagara and in other

parts of the Niagara Peninsula had formerly belonged to Butler's Rangers,

a regiment of cavalry who carried on a guerilla warfare against the

revolutionary party of the United States, their operations being confined

principally to the eastern parts of the States of New York and

Pennsylvania. They were accused of laying waste the country, destroying

property, and burning buildings. Many atrocities were laid to their

charge, however, which were quite unsupported by the facts, and where

offences were committed the actual facts were greatly exaggerated. It is

true that war at any time is cruel and relentless, and many things are

done that at another period would be considered barbarous. Most of the

Indian tribes of New York State sided with Great Britain and made frequent

raids on the American settlements. It is possible that the onus of their

evil work may have been placed upon Butler's Rangers. In their raids the

Rangers were associated with Indian allies. It is quite probable that many

of the atrocities attributed to the Rangers were perpetrated by the

Indians connected with them, and whose well-known ferocity when on the

war-path the Rangers themselves were unable to restrain.

The Indians, it is true, may have

been assisted by some few cruel white men, fiends in human form, who

unfortunately got a footing amongst Butler's Rangers; but the general

opinion has been long since arrived at that most of these stories were

gotten up by the Americans in order to excite the American people to

revenge. General Sullivan, who was sent by the United States Government to

make raids on the Loyalist settlements of New York State, is reported to

have been guilty of just as much cruelty as the Rangers were ever charged

with. A Ranger descendant told the writer that his father always said the

stories of the cruelty of Butler's Rangers were at first manufactured and

afterwards adopted as American history yet we well know that in American

history there has been a great deal of falsification of the actual facts

when relating to anything pertaining to Canada, and They even now admit

some of the mistakes themselves. When war is being waged there is a great

tendency to exaggerate and falsify, anyway. Take, for instance, the

reports sent out by the Beers during the late Boer-British War in South

Africa. It is not denied that some of those who had belonged to Butler's

Rangers were a rough class—there are always such who follow the fortunes

of war—and were known to boast of the cruelties they had committed; but

how do we know that they were always telling the truth? They may have told

these stories to excite the awe and terror of the children of the people

among whom they lived. We all know the proneness of such characters to

exaggeration. The poet Campbell has given a pathetic description of the

descent of the Rangers into the Valley of Wyoming, in his poem entitled

"Gertrude of Wyoming." It was proved to him afterwards, however, that the

facts upon which he based his poem were quite baseless and without

foundation. Just how much truth there was in the stories of the alleged

cruelties of these Rangers may never be fully known; but the fact remains,

and can be fully vouched for by some of the old people still living, that

horrid stories concerning them, such as the killing of innocent women and

children, the burning of their homes, dangling infant children on their

bayonets over the fire, and other equally revolting fireside anecdotes of

admitted doubtful veracity, were common talk among the old settlers, both

Loyalist and otherwise, in every section of the country, and talked and

told over and over again, just for talk's sake.

The common saying that none of the

Rangers were known to die a natural death was but one amongst the many

other exaggerations as we know from ocular proof to the contrary. As has

just been said, it is admitted that some of the Rangers were of a low type

of men. But one black sheep or two should not be accepted as true

representatives of a hardy, courageous and enterprising. type of guerilla

soldiers. Here is an instance that will explain our meaning: One of the

old Rangers, who lived alone on the Niagara, was the dread of the women

and children in the neighborhood on account of the frightful stories he

told. When he died, it is said, the coffin would not stay in the ground,

but one end kept coming to the surface. The superstitious people in the

neighborhood attributed this fact to his wickedness, whereas the real

cause was quicksand! Some few of the Loyalists, on account of the hardship

and ill-treatment they were subjected to by the rebel party, were filled

with the spirit of resentment. And who can scarcely wonder at this? It was

the result of despair.

In one instance, known to the

writer, the American soldiers came to the house, and demanded the young

men of the family; when told they were away they shot the old father of

the family, without any provocation, on his own threshold. And other cases

of this kind, equally barbarous and unjustifiable, might be given. One

thing must ever remain to the credit of the Rangers —their adherence to

principle.

"Their loyalty was still the same

Whether they lost or won the game."

When talking over facts of history

that occurred during war time a century and a quarter ago, we must

remember that military discipline and martial law were very severe then,

much more so than at the present day. At that time, even during peace,

persons were hung for forgery and sheep stealing. Alen had no heart or

"bowels of compassion"; victory must he gained at all hazards, and no

matter at what sacrifice. It is said that the military men who settled at

Niagara were of a stern character, and had no conscience when it came to

carrying out military discipline and stratagem.. This was the class of men

Col. Murray took with him for the attack on Fort Niagara, on the night of

December 19th, 1813. The orders were that not a soul should live between

the landing-place and the fort. This was to prevent anyone from notifying

the garrison of the fort of the approach of the enemy. The attack on Fort

Niagara was said to have been in retaliation for the burning of Niagara by

the Americans. The inhabitants were only given half an hour's notice by

the American general, and that on a bitter cold December day. It can

safely be said of the descendants of most of these old soldiers of the

Revolution, however, that they have proved an honorable and honest class

of men in every relation of life.

The Mennonites and Tunkers.

The Mennonites were among the

earliest settlers in Upper Canada. Many of them settled in Welland and

Lincoln counties previous to 1800, and in that year their settlement in

Waterloo County began, Waterloo Township being bought by a company of

these people. Markham, Vaughan, and Whitchurch townships, in York County,

were settled largely by members of this sect. Through marriage and social

intercourse with English-speaking people their language and peculiar

customs are fast disappearing, and it looks as if in the course of a very

few years there would be nothing left but their family name and their

religion, which some of them still adhere to, to distinguish them from

other people.

The early Mennonite settlers must

not be classed, however, with the Russian Mennonites who settled in

Manitoba more than a quarter of a century ago, although originally of the

same stock. Although being like the Quakers, a non-fighting class of

people, we think the early settlers of this class might properly be called

United Empire Loyalists. Their sympathies in the Revolutionary War were

certainly with Great Britain, although, in consonance with their religious

belief, they refused to bear arms for either party. They were honest,

God-fearing, industrious people, many of whom left Pennsylvania and came

to Canada for the reason that the British Government granted them

exemption from military service, and allowed them to make an affirmation

instead of taking an oath or making an affidavit in the courts, which

privilege they were not sure of being able to retain under the government

of the United States.

Their religion was opposed to war

and going to law. In this respect they resembled the Quakers. Their

ancestors emigrated from Switzerland and the Palatinate along the Rhine

early in the eighteenth century, and settled in the commonwealths of

Pennsylvania and Maryland. Many of their descendants are to be found yet

in those states, some of them still retaining the language, religion,

style of dress, habits and customs of their German ancestors, although for

the last fifty years there has been a gradual breaking away from the

primitive customs which their forefathers brought with them from the

fatherland and maintained so well for more than a hundred years.

It is no longer considered wrong

for their children to marry English-speaking people of other faiths. At

one time if one of the family married outside of their own people they

were sure to incur the anger and estrangement of their parents. It was no

uncommon thing to find young people who had never entered any church but

that of their own denomination. Although not by any means an ignorant

class of people, they were a simple-minded folk; all the education that

was considered necessary among them being a good understanding of the

three Rs: "Reading, 'Riting, and 'Rithmetic." Many of them were great

readers; their reading, however, being confined to books of a religious

character. Although not deeply versed in learning, they were and are a

thinking class of people. As is quite apparent from the thrifty manner in

which they conduct their business, which was and is chiefly in the

agricultural line.

The Tunkers (or Brethren) belonged to the same race

of people and spoke the same language as the Mennonites, most of them in

the early days being converts from the faith of the latter. Their customs

and habits of living were similar. Their style of dress, however, was

somewhat different. In religion they differed chiefly in the form of

worship and tenets of their faith.

|