|

THE OLD WATER WHEEL—THE OLD SAWMILLS—THE WINDMILLS—THE OLD-TIME

WINTER—VIEWS OF THE NIAGARA.

PREVIOUS to the introduction of the steam

engine the saw and grist mills in the

country were operated by water power, with the

exception of a few grist mills run by wind and called windmills. (See page

237.) These mills, being situated on some running stream where water-power

could be obtained, were widely separated on account of the scarcity of

suitable locations and the expense of building and keeping up a dam. In

some localities when the water was low the mill had to remain idle and

unproductive for months. The water was conducted from the dam or pond by a

race course and was carried by the "flume," a long wooden box, sometimes

placed on trestle-work, to the it stock" over the wheel, where it was held

by a gate or sluice, which could be raised or lowered as desired, so as to

let the water fall into the buckets of the big wooden wheel, causing the

wheel to revolve and turning the shaft connected with

the gearing of the mill. The larger the wheel the greater the power. Some

of the old "overshot" wheels were as much as thirty-six feet in diameter

and over ninety feet in circumference, with a shaft two or three feet

through. The ordinary wheel had a diameter of from twelve to fifteen feet,

the flow of water in many cases not being sufficient to operate a very

large wheel. They were not left exposed, as they usually appear to have

been in the Old Country according to pictures we see, but were built over

or boxed in to protect them from the weather, the drouth of summer and the

frost and snow of winter. Later on the "undershot" wheel was invented and

was made to turn by having a stream of water, flowing underneath, strike

the paddles of the wheel. It was not so large as the overshot wheel. It

was, however, claimed that the undershot wheel required one-third less

power than the overshot. Both these wheels were superseded about forty

years ago by the iron turbine wheel, which gives far more power than

either of the old-fashioned wheels, the water flowing to the centre or

axle of the wheel. The turbine is smaller than either of the others. The

mill-dams, usually built of logs, mud, plank and posts, often gave way in

the spring and fall by the action of the frost and the force of the water

during a freshet, and the repairing of them entailed a vast amount of

labor and expense, as is also at present the ease.

The Old Sawmills.

Here and there, where suitable locations could be obtained along the

rivers and creeks, could be seen the old sawmill with its water wheel,

flume, or race course, and dam for supplying water for power, and with

heaps of saw-logs piled around ready to be converted into lumber for the

settler. Usually, in the early days, when money was scarce the lumber was

sawed on shares. When sawmills were not easy of access some of the pioneer

settlers, from sixty to seventy-five years ago and earlier, sawed what

lumber they needed with the "whip-saw." A hole was dug in the ground over

which the log was rolled. The saw was drawn up and down by a man on top,

the "top-sawyer," and a man or two below, with goggles or a veil on to

keep the sawdust out of their eyes. This was a slow way of sawing lumber,

but 'the settlers were compelled to resort to this method at times to get

what lumber they needed. Sometimes a platform was built on the side of a

hill and the log rolled on from above. In shipyards to this day lumber for

certain parts of the ship is sawn in this way. Lumber was scarce in the

early days, sawmills being, as before remarked, few and far between. The

sawing had to be done in the fall, winter and spring, as in the summer the

water was generally too low for the purpose.

The Windmills.

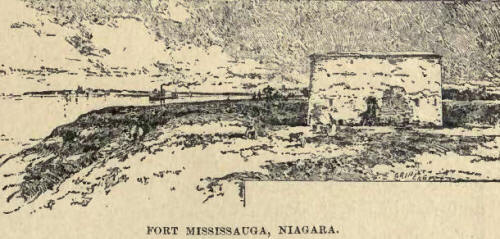

There were quite a few windmills in the country early in the century, and

where they were to be found they formed one of the marked features of the

landscape, the old windmills at Fort Erie, Niagara and Windmill Point, in

Prescott, being historical landmarks. The windmill was one of the most

conspicuous buildings then to be seen on the face of the country. In a

picture of Toronto, probably a hundred years old, in the possession of the

Canadian Institute, the old windmill stands out prominently. The

windmills, being built on level ground or in elevated places could be seen

from afar off, and with their spreading wooden

fans looked like some huge butterfly against the sky. They are a very

ancient form of power, and where water-power could not be easily obtained,

before the days of steam- power, they came in very handy for grist-mill

purposes. The old-fashioned windmills must not be confounded, however,

with the windmills of the present day, with their iron fans, to be seen

connected with so many up- to-date farm buildings, and which are used for

grinding feed and drawing water for the stock.

The Old-Time Winter.

During the last hundred years careful observation goes to show that the

climate has been changing considerably. Many attribute this to the cutting

down of the forests. The winters are not nearly as

severe as formerly. In the olden time the snow was generally very deep,

and often covered the ground from November to April. The farmers would go

out with their teams (oxen and horses) the morning after a heavy fall of

snow, and "break the roads." Oftentimes they would make a gap in a rail

fence and allow the people to drive through the fields, or perhaps the

journey would be made over the ice on the river until they arrived at a

point where the road was passable.

What a comfortable picture on a frosty winter's day is

a backwoodsman's log house situated in a clearing, white with snow, with

the smoke from the chimney curling up through the tree tops, the cows

standing around in the barn yard, the dog whisking around the door? It is,

to the mind of the writer, a picture of comfort more perfect than that of

a cold stone mansion on a palatial city street. It gives one an idea of a

phase of life which might be described as living "near to nature's heart."

In the winter time the children would gather on the

side of some hill, and with their home-made sleds, with runners made of

natural crooks or of boards, and shod with pieces of hoop-iron or hickory,

make the air resound with their shouts, as they joyfully sped down the

hill and out over the ice on the pond or river. This was making "the

welkin ring."

Skating was a common and healthy exercise, especially for those who lived

near the shores of the lakes, rivers and creeks. It afforded a means of

locomotion in the wintertime, which in summer was changed for the

row-boat, canoe or dug-out, the latter hollowed out of a log.

Views of the Niagara.

Anyone that has been born and raised on the old Niagara or has spent part

of his childhood days there, must love the old

river, its sights and its sounds. To those living above the falls there is

always the knowledge of the fact that the mighty cataract is below them,

which they must use caution in avoiding. This, of itself, gives a certain

feeling of excitement and apprehension when crossing the river above this

point. There are also the many sights which the youth, unharassed by the

world's anxieties and cares, cannot fail to enjoy, and which remain

indelibly impressed upon his mind wherever he may roam. The wharves

extending out into the river here and there, the poplar points showing

themselves above the surrounding landscape, the tugs steaming back and

forth on the river, the spires of the churches pointing heavenward, the

pretty recreation houses and grounds on the American side of the river,

frequented by the pleasure-seekers from Buffalo—all bring back fond

recollections to his memory. He returned to find that,

after all his wanderings, the sun never shone any brighter, the air never

felt more balmy in any spot than it used to in his childhood days on the

old Niagara. A drive along the river road at sunrise, with the reflection

of the morning sun on the waters, with the dark woods of Navy Island

looming up in the distance, recalling- the time when the rebels, in 1837,

made it their rendezvous and fired their cannon balls towards the main

shore, is an enjoyment not forgotten in a lifetime. The scene from the

bank of the river on a fine moonlight night, the light from the moon

shining on the rippling waters and causing them to sparkle like myriads of

diamonds, the sound of merry voices from the water to the regular

accompaniment and the movement of the oars, all so distinctly heard at

times across the river, is another delight only to be felt at old Niagara.

In the winter time, however, the river looks lonely and forsaken. An uncle

of the writer, many years ago, came very nearly being swept over the

falls, lie was but a child of three or four years of age at the time.

Unnoticed, he got into a boat moored on the bank of the river in front of

his father's house. The boat became unfastened and was swept out into the

middle of the stream. As the current bore it downward some of the family

noticed the boy alone in the boat. It so happened that just then no other

boat could be got to reach the boy. His father, however, followed him down

the river bank for several miles, but still could not find another boat.

Finally, when about three miles from home and about the same distance from

the falls, by calling loudly providentially he attracted the attention of

a woman on the opposite shore, about three-quarters of a mile away. This

good woman bade her son, who was painting a boat on the bank, right the

boat he was painting and shove out into the stream to the rescue. Had the

boat with the child floated much further down the stream it would have got

into the strong current and been swiftly borne over the falls. It was a

narrow escape, which gave the family much cause for thankfulness.

|