|

IN the year 1832 I

landed with my husband, J. W. Dunbar Moodie, in Canada. Mr. Moodie was

the youngest son of Major Moodie, of Mellsetter, in the Orkney Islands ;

he was a lieutenant in the 21st regiment of Fusileers, and had been

severely wounded in the night-attack upon Bergen-op-Zoom, in Holland.

Not being overgifted

with the good things of this world—the younger sons of old British

families seldom are—he had, after mature deliberation, determined to try

his fortunes in Canada, and settle upon the grant of 400 acres of land,

ceded by the Government to officers upon half-pay.

Emigration, in most

cases—and ours was no exception to the general rule—is a matter of

necessity, not of choice. It may, indeed, generally be regarded as an

act of duty performed at the expense of personal enjoyment, and at the

sacrifice of all those local attachments which stamp the scenes in which

our childhood grew in imperishable characters upon the heart.

Nor is it, until

adversity has pressed hard upon the wounded spirit of the sons and

daughters of old, but impoverished, families, that they can subdue their

proud and rebellious feelings, and submit to make the trial.

This was our case, and

our motive for emigrating to one of the British colonies can be summed

up in a few words.

The emigrant’s hope of

bettering his condition, and securing a sufficient competence to support

his family, to free himself from the slighting remarks, too often hurled

at the poor gentleman by the practical people of the world, which is

always galling to a proud man, but doubly scf, when he knows that the

want of wealth constitutes the sole difference between him and the more

favored offspring of the same parent stock.

In 1830 the tide of

emigration flowed westward, and Canada became the great land-mark for

the rich in hope and poor in purse. Public newspapers and private

letters teemed with the almost fabulous advantages to be derived from a

settlement in this highly favored region. Men, who had been doubtful of

supporting their families in comfort at home, thought that they had only

to land in Canada to realize a fortune. The infection became general.

Thousands and tens of thousands from the middle ranks of British

society, for the space of three or four years, landed upon these shores.

A large majority of these emigrants were officers of the army and navy,

with their families; a class perfectly unfitted, by their previous

habits and standing in society, for contending with the stern realities

of emigrant life in the baek-woods. A class formed mainly from the

younger scions of great families, naturally proud, and not only

accustomed to command, but to receive implicit obedience from the people

unuer them, are not men adapted to the hard toil of the woodman’s life.

Nor will such persons submit cheerfully to the saucy familiarity of

servants, who, republicans at heart, think themselves quite as good as

their employers.

Too many of these brave

and honest men took up their grants of wild land in remote and

unfavorable localities, far from churches, schools, and markets, and

fell an easy prey to the land speculators, that swarmed in every rising

village on the borders of civilization.

It was to warn such

settlers as these last mentioned, not to take up grants and pitch their

tents in the wilderness, and by so doing, reduce themselves and their

families to hopeless poverty, that my work “ Roughing it in the Bush”

was written.

I gave the experience

of the first seven years we passed in the woods, attempting to clear a

bush farm, as warning to others, and the number of persons who have

since told me, that my book “told the history” of their own life in the

woods, ought to be the best proof to every candid mind that I spoke the

truth. It is not by such feeble instuments as the above that Providence

works, when it seeks to reclaim the waste places of the earth, and make

them subservient to the wants and happiness of its creatures. The great

Father of the souls and bodie3 of men knows the arm which wholesome

labour from infancy has made strong, the nerve3 that have become iron by

patient endurance, and he chooses such to send forth into the forest to

hew out the rough paths for the advance of civilization.

These men become

wealthy and prosperous, and are the bones and sinews of a great and

rising country. Their labour is wealth, not exhaustion; it produce^

content, not home sickness and despair.

What the backwoods

of Canada are to the industrious and ever-to-be-honored sons of

honest poverty, and what they are to the refined and polished

gentleman, these sketches have endeavored to show.

The poor man is in

his native element; the poor gentleman totally unfitted, by his

previous habits and education, to be a hewer of the forest, and a

tiller of the soil. What money he brought out with him is lavishly

expended during the first two years, in paying for labour to clear

and fence lands, which, from his ignorance of agricultural pursuits,

will never make him the least profitable return, and barely find

coarse food for his family. Of clothing we say nothing. Bare feet

and rags are too common in the bush.

Now, had the same

means and the same labour been employed in the cultivation of a

leased farm, or one purchased for a few hundred dollars, near a

village, how different would have been the results, not only to the

settler, but it would have added greatly to the wealth and social

improvement of the country.

I am well aware that a

great, and, I must think, a most unjust prejudice has been felt against

my book in Canada, because I dared to give my opinion freely on a

subject which had engrossed a great deal of my attention; nor do I

believe that the account of our failure in the bush ever deterred a

single emigrant from coming to the country, as the only circulation it

over had in the colony, was chiefly through the volumes that often

formed a portion of their baggage. The many, who have condemned the work

without reading it, will be surprised to find that not one word has been

said to prejudice intending emigrants from making Canada their home.

Unless, indeed, they ascribe the regret expressed at having to leave my

native land, so natural in the painful home-sickness which, for several

months, preys upon the health and spirits of the dejected exile, to a

deep-rooted dislike to the country.

So far from this being

the case, my love for the country has steadily increased, from year to

year, and my attachment to Canada is now so strong, that I cannot

imagine any inducement, short of absolute necessity, which could induce

me to leave the colony, where, as a wife and mother, some of the

happiest years of my life have been spent.

Contrasting the first

years of my life in the bush, with Canada as she now is, my mind is

filled with wonder and gratitude at the rapid strides she has made

towards the fulfilment of a great and glorious destiny.

What important, events

have been brought to pass within the narrow circle of less than forty

years! What a difference since now and then. The country is the same

only in name. Its aspect is wholly changed. The rough has become smooth,

the crooked has been made straight, the forests have been converted into

fruitful fields, the rude log cabin of the woodsman has been replaced by

the handsome, well appointed homestead, and large populous cities have

pushed the small clap-boarded village into the shade.

The solitary stroke of

the axe, that once broke the uniform silence of the vast woods, is only

heard in remote districts, and is superseded by the thundering tread of

the iron horse, and the ceaseless panting of the steam engine in our saw

mills and factories.

Canada is no longer a

child, sleeping in the arms of nature, dependent for her very existence

on the fostering care of her illustrious mother. She has outstepped

infancy, and is in the full enjoyment of a strong and vigorous youth.

What may not we hope for her maturity ere another forty summers have

glided down the stream of time. Already she holds in her hand the crown

of one of the mightiest empires that the world has seen, or is yet to

see.

Look at her vast

resources—her fine healthy climate— her fruitful soil—the inexhaustible

wealth of her pine forests—the untold treasures hidden in her unexplored

mines. What other country possesses such an internal navigation for

transporting its products from distant Manitoba to the sea, and from

thence to every port in the world!

If an excellent

Government, defended by wise laws, a loyal people, and a free Church can

make people happy and proud of their country, surely we have every

reason to rejoice in our new Dominion.

When we first came to

the country it was a mere struggle for bread to the many, while all the

offices of emolument and power were held by a favored few. The

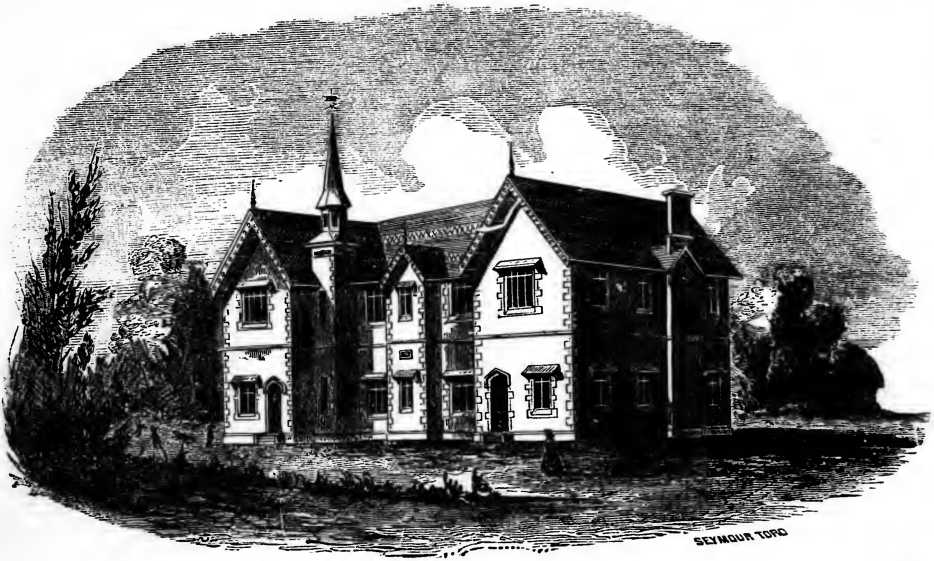

PUBLIC SCHOOL

country was rent to

pieces by political factions, and a fierce hostility existed between the

native born Canadians —the first pioneers of the forest—and the British

emigrants, who looked upon each other as mutual enemies who were seeking

to appropriate the larger share of the new country.

Those who had settled

down in the woods, were happily unconscious that these quarrels

threatened to destroy the peace of the colony.

The insurrection of

1837 came upon them like a thunder clap; they could hardly believe such

an incredible tale. Intensely loyal, the emigrant officers rose to a man

to defend the British flag, and chastise the rebels and their rash

leader.

In their zeal to uphold

British authority, they made no excuse for the wrongs that the dominant

party had heaped upon a clever and high-spirited man. To them he was a

traitor; and as such, a public enemy. Yet the blow struck by that

injured man, weak as it was, without money, arms, or the necessary

munitions of war, and defeated and broken in its first effort, gave

freedom to Canada, and laid the foundation of the excellent constitution

that we now enjoy. It drew the attention of the Home Government to the

many abuses then practised in the colony; and made them aware of its

vast importance in a political point of view; and ultimately led to all

our great national improvements.

The settlement of the

long vexed clergy reserves question, and the establishment of common

schools, was a great boon to the colony. The opening up of new

townships, the making of roads, the establishment of municipal councils

in all the old districts, leaving to the citizens the free choice of

their own members in the council for the management of their affairs,

followed in rapid succession.

These changes of course

took some years to accomplish, and led to others equally important. The

Provincial Exhibitions have done much to improve the agricultural

interests, and have led to better and more productive methods of

cultivation, than were formerly practised in the Province. The farmer

gradually became a wealthy and intelligent land owner, proud of his

improved flocks and herds, of his fine horses, and handsome homestead.

He was able to send his sons to college and his daughters to boarding

school, and not uncommonly became an honorable member of the Legislative

Council.

While the sons of poor

gentlemen have generally lost caste, and sunk into useless sots, the

children of these honest tillers of the soil have steadily risen to the

highest class; and have given to Canada some of her best and wisest

legislators.

Men who rest satisfied

with the mere accident of birth for their claims to distinction, without

energy and industry to maintain their position in society, are sadly at

discount in a country, which amply rewards the worker, but leaves the

indolent loafer to die in indigence and obscurity.

Honest poverty is

encouraged, not despised, in Canada.

Few of her prosperous

men have risen from obscurity to affluence without going through the

mill, and therefore have a fellow-feeling for those who are struggling

to gain the first rung on the ladder.

Men are allowed in this

country a freedom enjoyed by few of the more polished countries in

Europe; freedom in religion, politics, and speech; freedom to select

their own friends and to visit with whom they please, without consulting

the Mrs. Grundys of society; and they can lead a more independent social

life than in the mother country, because less restricted by the

conventional prejudices that govern older communities.

Few people who have

lived many years in Canada, and return to England to spend the remainder

of their days, accomplish the fact. They almost invariably come back,

and why? They feel more independent and happier here; they have no idea

what a blessed country it is to live in until they go back and realize

the want of social freedom. I have heard this from so many educated

people, persons of taste and refinement, that I cannot doubt the truth

of their statements.

Forty years has

accomplished as great a change in the habits and tastes of the Canadian

people, as it has in the architecture of their fine cities, and the

appearance of the country. A young Canadian gentleman is as well

educated as any of his compeers across the big water, and contrasts very

favourably with them. Social and unaffected, he puts on no airs of

offensive superiority, but meets a stranger with the courtesy and

frankness best calculated to shorten the distance between them, and to

make Ins guest feel perfectly at homo.

Few countries possess a

more beautiful female population. The women are elegant in their tastes,

graceful in their manners, and naturally kind and affectionate in their

dispositions. ’Good housekeepers, sociable neighbours, and lively and

active in speech and movement; they are capital companions, and make

excellent wives and mothers. Of course there must be exceptions to every

rule; but cases of divorce, or desertion of their homes, are so rare an

occurrence, that it speaks volumes for their domestic worth. Numbers of

British officers have chosen their wives in Canada, and I never heard

that they had cause to repent of their choice.

In common with our

American neighbours, we find that the worst members of our community are

not Canadian born, but importations from other countries.

The Dominion and Local

Governments are now doing much to open up the resources of Canada, by

the Intercolonial and projected Pacific Railways, and other Public

Works, which, in time, will make a vast tract of land available for

cultivation, and furnish homes for multitudes of the starving

populations of Europe.

And age in, the

Government of the flourishing Province of Ontario,—of which the Hon. J.

Sandfield Macdonald is premier—has done wonders during the last four

years by means of its Immigration policy, which has been most

successfully carried out by the Hon. John Carling, the Commissioner, and

greatly tended to the development of the country. By this policy liberal

provision is made for free grants of land to actual settlers, for

general education, and for the encouragement of the industrial Arts and

Agriculture; by the construction of public roads, and the improvement of

tho internal navigable waters of the Province; and by the assistance now

given to an economical system of railways connecting these interior

waters with the leading railroads and ports on the frontier ; and not

only are free grants of land given in the districts extending from the

eastern to the western extremity of the Province, but one of the best of

the new townships has been selected in which the Government is now

making roads, and upon each lot is clearing five acres and erecting

thereon a small house, which will be granted to heads of families, who,

by six annual instalments, will be required to pay back to the

Government the cost of these improvements—not exceeding $200, or £40

sterling—when a free patent (or deed) of the land will be given, without

any charge whatever, under a protective Homestead Act. This wise and

liberal policy would have astonished the Colonial Legislature of 1832;

but will, no doubt, speedily give to the Province a noble and

progressive back country, and add much to its strength and prosperity.

Our busy factories and

foundries—our copper, silver and plumbago mines—our salt and

petroleum—the increasing exports of native produce—speak volumes for the

prosperity of the Dominion, and for the government of those who are at

the head of affairs. It only requires the loyal co-operation of an

intelligent and enlightened people, to render this beautiful and free

country the greatest and the happiest upon the face of the earth.

When we contrast forest

life in Canada forty years ago, with the present state of the country,

my book will not be without interest and significance. 'We may truly

say, old things have passed away, all things have become new.

What an advance in the

arts and sciences, and in the literature of the country has been made

during the last few years. Canada can boast of many good and even

distinguished authors, and the love of books and book-lore is daily

increasing.

Institutes and literary

associations for the encouragement of learning are now to be found in

all the cities and large towns in the Dominion. We are no longer

dependent upon the States for the reproduction of the works of

celebrated authors; our own publishers, both in Toronto and Montreal,

are furnishing our handsome book stores with volumes that rival, in

cheapness and typographical excellence, the best issues from the large

printing establishments in America. We have no lack of native talent or

books, or of intelligent readers to appreciate them.

Our print shops are

full of the well-executed designs of native artists. And the grand

scenery of our lakes and forests, transferred to canvas, adorns the

homes of our wealthy citizens.

We must not omit in

this slight sketch to refer to the number of fine public buildings,

which meet us at every turn, most of which have been designed and

executed by native architects. Montreal can point to her Victoria

Bridge, and challenge the world to produce its equal. This prodigy of

mechanical skill should be a sufficient inducement to strangers from

other lands to visit our shores, and though designed by the son of the

immortal George Stephenson, it was Canadian hands that helped him to

execute his great project—to raise that glorious monument to his fame,

which, we hope, will outlast a thousand years.

Our new Houses of

Parliament, our churches, banks public halls, asylums for the insane,

the blind, and the deaf and dumb, are buildings which must attract the

attention of every intelligent traveller; and when we consider the few

brief years that have elapsed since the Upper Province was reclaimed

from the wilderness, our progress in mechanical arts, and all the

comforts which pertain to modern civilization, is unprecedented in the

history of older nations.

If the Canadian people

will honestly unite in carrying out measures proposed by the Government,

for the good of the country, irrespective of self-interest and party

prejudices, they must, before the close of the present century, become a

great and prosperous people, bearing their own flag, and enjoying their

own nationality. May the blessing of God rest upon Canada and the

Canadian people!

Susanna Moodie.

Belleville, 1871 |