|

Perhaps Lucien would have carried his account of the

marmots still farther—for he had not told half what he knew of their

habits—but he was at that moment interrupted by the marmots themselves.

Several of them appeared at the mouths of their holes; and, after

looking out and reconnoitring for some moments, became bolder, and ran

up to the tops of their mounds, and began to scatter along the little

beaten paths that led from one to the other. In a short while as many as

a dozen could be seen moving about, jerking their tails, and at

intervals uttering their “seek-seek.”

Our voyageurs saw that there were two kinds of them,

entirely different in colour, size, and other respects. The larger ones

were of a greyish yellow above, with an orange tint upon the throat and

belly. These were the “tawny marmots,” called sometimes

“ground-squirrels,” and by the voyageurs, “siffleurs,” or “whistlers.”

The other species seen were the most beautiful of all the marmots. They

were very little smaller than the tawny marmots; but their tails were

larger and more slender, which rendered their appearance more graceful.

Their chief beauty, however, lay in their colours and markings. They

were striped from the nose to the rump with bands of yellow and

chocolate colour, which alternated with each other, while the chocolate

bands were themselves variegated by rows of yellow spots regularly

placed. These markings gave the animals that peculiar appearance so

well-known as characterising the skin of the leopard, hence the name of

these little creatures was “leopard-marmots.”

It was plain from their actions that both kinds were “at

home” among the mounds, and that both had their burrows there. This was

the fact, and Norman told his companion that the two kinds are always

found together, not living in the same houses, but only as neighbours in

the same “settlement.” The burrows of the “leopard” have much smaller

entrances than those of their “tawny kin,” and run down perpendicularly

to a greater depth before branching off in a horizontal direction. A

straight stick may be thrust down one of these full five feet before

reaching an “elbow.” The holes of the tawny marmots, on the contrary,

branch off near the surface, and are not so deep under ground. This

guides us to the explanation of a singular fact—which is, that the

“tawnies” make their appearance three weeks earlier in spring than the

“leopards,” in consequence of the heat of the sun reaching them sooner,

and waking them out of their torpid sleep.

While these explanations were passing among the boys, the

marmots had come out, to the number of a score, and were carrying on

their gambols along the declivity of the hill. They were at too great a

distance to heed the movements of the travellers by the camp-fire.

Besides, a considerable valley lay between them and the camp, which, as

they believed, rendered their position secure. They were not at such a

distance but that many of their movements could be clearly made out by

the boys, who after a while noticed that several furious battles were

being fought among them. It was not the “tawnies” against the others,

but the males of each kind in single combats with one another. They

fought like little cats, exhibiting the highest degree of boldness and

fury; but it was noticed that in these conflicts the leopards were far

more active and spiteful than their kinsmen. In observing them through

his glass Lucien noticed that they frequently seized each other by the

tails, and he further noticed that several of them had their tails much

shorter than the rest. Norman said that these had been bitten off in

their battles; and, moreover, that it was a rare thing to find among the

males, or “bucks,” as he called them, one that had a perfect tail!

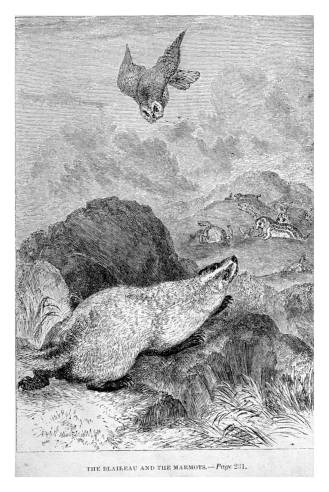

While these observations were being made, the attention

of our party was attracted to a strange animal that was seen slowly

crawling around the hill. It was a creature about as big as an ordinary

setter dog, but much thicker in the body, shorter in the legs, and

shaggier in the coat. Its head was flat, and its ears short and rounded.

Its hair was long, rough, and of a mottled hoary grey colour, but

dark-brown upon the legs and tail. The latter, though covered with long

hair, was short, and carried upright; and upon the broad feet of the

animal could be seen long and strong curving claws. Its snout was sharp

as that of a greyhound—though not so prettily formed—and a white stripe,

passing from its very tip over the crown, and bordered by two darker

bands, gave a singular expression to the animal’s countenance. It was

altogether, both in form and feature, a strange and vicious-looking

creature. Norman recognised it at once as the “blaireau,” or American

badger. The others had never seen such a creature before—as it is not an

inhabitant of the South, nor of any part of the settled portion of the

United States, for the animal there sometimes called a badger is the

ground-hog, or Maryland marmot (Arctomys monax). Indeed, it was for a

long time believed that no true badger inhabited the Continent of

America. Now, however, it is known that such exists, although it is of a

species distinct from the badger of Europe. It is less in size than the

latter, and its fur is longer, finer, and lighter in colour; but it is

also more voracious in its habits, preying constantly upon mice,

marmots, and other small animals, and feeding upon carcasses, whenever

it chances to meet with such. It is an inhabitant of the sandy and

barren districts, where it burrows the earth in such a manner that

horses frequently sink and snap their legs in the hollow ground made by

it. These are not always the holes scraped out for its own residence,

but the burrows of the marmots, which the blaireau has enlarged, so that

it may enter and prey upon them. In this way the creature obtains most

of its food, but as the marmots lie torpid during the winter months, and

the ground above them is frozen as hard as a rock, it is then impossible

for the blaireau to effect an entrance. At this season it would

undoubtedly starve had not Nature provided against such a result, by

giving it the power of sleeping throughout the winter months as well as

the marmots themselves, which it does. As soon as it wakes up and comes

abroad, it begins its campaign against these little creatures; and it

prefers, above all others, the “tawnies,” and the beautiful “leopards,”

both of which it persecutes incessantly.

The

badger when first seen was creeping along with its belly almost dragging

the ground, and its long snout projected horizontally in the direction

of the marmot “village.” It was evidently meditating a surprise of the

inhabitants. Now and then it would stop, like a pointer dog when close

to a partridge, reconnoitre a moment, and then go on again. Its design

appeared to be to get between the marmots and their burrows, intercept

some of them, and get a hold of them without the trouble of digging them

up—although that would be no great affair to it, for so strong are its

fore-arms and claws that in loose soil it can make its way under the

ground as fast as a mole. The

badger when first seen was creeping along with its belly almost dragging

the ground, and its long snout projected horizontally in the direction

of the marmot “village.” It was evidently meditating a surprise of the

inhabitants. Now and then it would stop, like a pointer dog when close

to a partridge, reconnoitre a moment, and then go on again. Its design

appeared to be to get between the marmots and their burrows, intercept

some of them, and get a hold of them without the trouble of digging them

up—although that would be no great affair to it, for so strong are its

fore-arms and claws that in loose soil it can make its way under the

ground as fast as a mole.

Slowly and cautiously it stole along, its hind-feet

resting all their length upon the ground, its hideous snout thrown

forward, and its eyes glaring with a voracious and hungry expression. It

had got within fifty paces of the marmots, and would, no doubt, have

succeeded in cutting off the retreat of some of them, but at that moment

a burrowing owl (Strix cunicularia), that had been perched upon one of

the mounds, rose up, and commenced hovering in circles above the

intruder. This drew the attention of the marmot sentries to their

well-known enemy, and their warning cry was followed by a general

scamper of both tawnies and leopards towards their respective burrows.

The blaireau, seeing that further concealment was no

longer of any use, raised himself higher upon his limbs, and sprang

forward in pursuit. He was too late, however, as the marmots had all got

into their holes, and their angry “seek-seek,” was heard proceeding from

various quarters out of the bowels of the earth. The blaireau only

hesitated long enough to select one of the burrows into which he was

sure a marmot had entered; and then, setting himself to his work, he

commenced throwing out the mould like a terrier. In a few seconds he was

half buried, and his hindquarters and tail alone remained above ground.

He would soon have disappeared entirely, but at that moment the boys,

directed and headed by Norman, ran up the hill, and seizing him by the

tail, endeavoured to jerk him back. That, however, was a task which they

could not accomplish, for first one and then another, and then Basil and

Norman—who were both strong boys—pulled with all their might, and could

not move him. Norman cautioned them against letting him go, as in a

moment’s time he would burrow beyond their reach. So they held on until

François had got his gun ready. This the latter soon did, and a load of

small shot was fired into the blaireau’s hips, which, although it did

not quite kill him, caused him to back out of the hole, and brought him

into the clutches of Marengo. A desperate struggle ensued, which ended

by the bloodhound doubling his vast black muzzle upon the throat of the

blaireau, and choking him to death in less than a dozen seconds; and

then his hide—the only part which was deemed of any value—was taken off

and carried to the camp. The carcass was left upon the face of the hill,

and the red shining object was soon espied by the buzzards and turkey

vultures, so that in a few minutes’ time several of these filthy birds

were seen hovering around, and alighting upon the hill.

But this was no new sight to our young voyageurs, and

soon ceased to be noticed by them. Another bird, of a different kind,

for a short time engaged their attention. It was a large hawk, which

Lucien, as soon as he saw it, pronounced to be one of the kind known as

buzzards (Buteo). Of these there are several species in North America,

but it is not to be supposed that there is any resemblance between them

and the buzzards just mentioned as having alighted by the carcass of the

blaireau. The latter, commonly called “turkey buzzards,” are true

vultures, and feed mostly, though not exclusively, on carrion; while the

“hawk buzzards” have all the appearance and general habits of the rest

of the falcon tribe.

The one in question, Lucien said, was the “marsh-hawk,”

sometimes also called the “hen-harrier” (Falco uliginosus). Norman

stated that it was known among the Indians of these parts as the

“snake-bird,” because it preys upon a species of small green snake that

is common on the plains of the Saskatchewan, and of which it is fonder

than of any other food.

The voyageurs were not long in having evidence of the

appropriateness of the Indian appellation; for these people, like other

savages, have the good habit of giving names that express some quality

or characteristic of the thing itself. The bird in question was on the

wing, and from its movements evidently searching for game. It sailed in

easy circlings near the surface, quartering the ground like a pointer

dog. It flew so lightly that its wings were not seen to move, and

throughout all its wheelings and turnings it appeared to be carried

onwards or upwards by the power of mere volition. Once or twice its

course brought it directly over the camp, and François had got hold of

his gun, with the intention of bringing it down, but on each occasion it

perceived his motions; and, soaring up like a paper-kite until out of

reach, it passed over the camp, and then sank down again upon the other

side, and continued its “quarterings” as before. For nearly half-an-hour

it went on manoeuvring in this way, when all at once it was seen to make

a sudden turning in the air as it fixed its eyes upon some object in the

grass. The next moment it glided diagonally towards the earth, and

poising itself for a moment above the surface, rose again with a small

green-coloured snake struggling in its talons. After ascending to some

height, it directed its flight towards a clump of trees, and was soon

lost to the view of our travellers.

Lucien now pointed out to his companions a characteristic

of the hawk and buzzard tribe, by which these birds can always be

distinguished from the true falcon. That peculiarity lay in the manner

of seizing their prey. The former skim forward upon it sideways—that is,

in a horizontal or diagonal direction, and pick it up in passing; while

the true falcons—as the merlin, the peregrine, the gerfalcon, and the

great eagle-falcons—shoot down upon their prey perpendicularly like an

arrow, or a piece of falling lead.

He pointed out, moreover, how the structure of the

different kinds of preying birds, such as the size and form of the wings

and tail, as well as other parts, were in each kind adapted to its

peculiar mode of pursuing its prey; and then there arose a discussion as

to whether this adaptation should be considered a cause or an effect.

Lucien succeeded in convincing his companions that the structure was the

effect and not the cause of the habit, for the young naturalist was a

firm believer in the changing and progressive system of nature. |