|

After remaining for some time on the nest along with the

others, the old male again resolved to “go a-fishing,” and with this

intent he shot out from the tree, and commenced wheeling above the

water. The boys, having nothing better to engage them, sat watching his

motions, while they freely conversed about his habits and other points

in his natural history. Lucien informed them that the osprey is a bird

common to both Continents, and that it is often seen upon the shores of

the Mediterranean, pursuing the finny tribes there, just as it does in

America. In some parts of Italy it is called the “leaden eagle,” because

its sudden heavy plunge upon the water is fancied to resemble the

falling of a piece of lead.

While they were discoursing, the osprey was seen to dip

once or twice towards the surface of the water, and then suddenly check

himself, and mount upward again. These manoeuvres were no doubt caused

by the fish which he intended to “hook” having suddenly shifted their

quarters. Most probably experience had taught them wisdom, and they knew

the osprey as their most terrible enemy. But they were not to escape him

at all times. As the boys watched the bird, he was seen to poise himself

for an instant in the air, then suddenly closing his wings, he shot

vertically downward. So rapid was his descent, that the eye could only

trace it like a bolt of lightning. There was a sharp whizzing sound in

the air—a plash was heard—then the smooth bosom of the water was seen to

break, and the white spray rose several feet above the surface. For an

instant the bird was no longer seen. He was underneath, and the place of

his descent was marked by a patch of foam. Only a single moment was he

out of sight. The next he emerged, and a few strokes of his broad wing

carried him into the air, while a large fish was seen griped in his

claws. As the voyageurs had before noticed, the fish was carried

head-foremost, and this led them to the conclusion that in striking his

prey beneath the water the osprey follows it and aims his blow from

behind.

After mounting a short distance the bird paused for a

moment in the air, and gave himself a shake, precisely as a dog would do

after coming out of water. He then directed his flight, now somewhat

slow and heavy, toward the nest. On reaching the tree, however, there

appeared to be some mismanagement. The fish caught among the branches as

he flew inward. Perhaps the presence of the camp had distracted his

attention, and rendered him less careful. At all events, the prey was

seen to drop from his talons; and bounding from branch to branch, went

tumbling down to the bottom of the tree.

Nothing could be more opportune than this, for François

had not been able to get a “nibble” during the whole day, and a fresh

fish for dinner was very desirable to all. François and Basil had both

started to their feet, in order to secure the fish before the osprey

should pounce down and pick it up; but Lucien assured them that they,

need be in no hurry about that, as the bird would not touch it again

after he had once let it fall. Hearing this, they took their time about

it, and walked leisurely up to the tree, where they found the fish

lying. After taking it up they were fain to escape from the spot, for

the effluvium arising from a mass of other fish that lay in a decomposed

state around the tree was more than any delicate pair of nostrils could

endure. The one they had secured proved to be a very fine salmon of not

less than six pounds weight, and therefore much heavier than the bird

itself! The track of the osprey’s talons was deeply marked; and by the

direction in which the creature was scored, it was evident the bird had

seized it from behind. The old hawks made a considerable noise while the

fish was being carried away; but they soon gave up their squealing, and,

once more hovering out over the river, sailed about with their eyes bent

upon the water below.

“What a number of fish they must kill!” said François.

“They don’t appear to have much difficulty about it. I should think they

get as much as they can eat. See! there again! Another, I declare!”

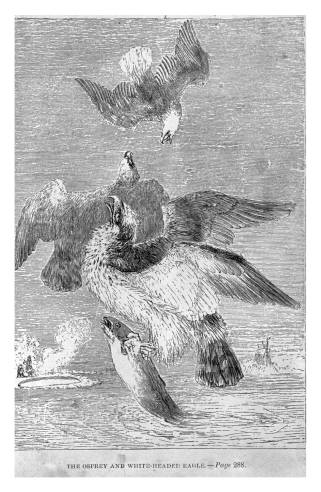

As François spake the male osprey was seen to shoot down

as before, and this time, although he appeared scarcely to dip his foot

in the water, rose up with a fish in his talons.

“They have sometimes others to provide for besides

themselves,” remarked Lucien. “For instance, the bald eagle—”

Lucien

was interrupted by a cackling scream, which was at once recognised as

that of the very bird whose name had just escaped his lips. All eyes

were instantly turned in the direction whence it came—which was from the

opposite side of the river—and there, just in the act of launching

itself from the top of a tall tree, was the great enemy of the

osprey—the white-headed eagle himself! Lucien

was interrupted by a cackling scream, which was at once recognised as

that of the very bird whose name had just escaped his lips. All eyes

were instantly turned in the direction whence it came—which was from the

opposite side of the river—and there, just in the act of launching

itself from the top of a tall tree, was the great enemy of the

osprey—the white-headed eagle himself!

“Now a chase!” cried François, “yonder comes the big

robber!”

With some excitement of feeling, the whole party watched

the movements of the birds. A few strokes of the eagle’s wing brought

him near; but the osprey had already heard his scream, and knowing it

was no use carrying the fish to his nest, turned away from it, and rose

spirally upward, in the hope of escaping in that direction. The eagle

followed, beating the air with his broad pinions, as he soared after.

Close behind him went the female osprey, uttering wild screams, flapping

her wings against his very beak, and endeavouring to distract his

attention from the chase. It was to no purpose, however, as the eagle

full well knew her object, and disregarding her impotent attempts, kept

on in steady flight after her mate. This continued until the birds had

reached a high elevation, and the ospreys, from their less bulk, were

nearly out of sight. But the voyageurs could see that the eagle was on

the point of overtaking the one that carried the fish. Presently, a

glittering object dropped down from the heavens, and fell with a plunge

upon the water. It was the fish, and almost at the same instant was

heard the “whish!” of the eagle, as the great bird shot after it. Before

reaching the surface, however, his white tail and wings were seen to

spread suddenly, checking his downward course; and then, with a scream

of disappointment, he flew off in a horizontal direction, and alit upon

the same tree from which he had taken his departure. In a minute after

the ospreys came shooting down, in a diagonal line, to their nest; and,

having arrived there, a loud and apparently angry consultation was

carried on for some time, in which the young birds bore as noisy a part

as either of their parents.

“It’s a wonder,” said Lucien, “the eagle missed the

fish—he rarely does. The impetus which he can give his body enables him

to overtake a falling object before it can reach the earth. Perhaps the

female osprey was in his way, and hindered him.”

“But why did he not pick it up in the water?” demanded

François.

“Because it went to the bottom, and he could not reach

it—that’s clear.”

It was Basil who made answer, and the reason he assigned

was the true one.

“It’s too bad,” said François, “that the osprey, not half

so big a bird, must support this great robber-tyrant by his industry.”

“It’s no worse than among our own kind,” interposed

Basil. “See how the white man makes the black one work for him here in

America. That, however, is the few toiling for the million. In Europe

the case is reversed. There, in every country, you see the million

toiling for the few—toiling to support an oligarchy in luxurious ease,

or a monarch in barbaric splendour.”

“But why do they do so? the fools!” asked François,

somewhat angrily.

“Because they know no better. That oligarchy, and those

monarchs, have taken precious care to educate and train them to the

belief that such is thenatural state of man. They furnish them with

school-books, which are filled with beautiful sophisms—all tending to

inculcate principles of endurance of wrong, and reverence for their

wrongers. They fill their rude throats with hurrah songs that paint

false patriotism in glowing colours, making loyalty—no matter to

whatsoever despot—the greatest of virtues, and revolution the greatest

of crimes; they studiously divide their subjects into several creeds,

and then, playing upon the worst of all passions—the passion of

religious bigotry—easily prevent their misguided helots from uniting

upon any point which would give them a real reform. Ah! it is a terrible

game which the present rulers of Europe are playing!”

It was Basil who gave utterance to these sentiments, for

the young republican of Louisiana had already begun to think strongly on

political subjects. No doubt Basil would one day be an M.C.

“The bald eagles have been much blamed for their

treatment of the ospreys, but,” said Lucien, “perhaps they have more

reason for levying their tax than at first appears. It has been asked:

Why they do not capture the fish themselves? Now, I apprehend, that

there is a natural reason why they do not. As you have seen, the fish

are not always caught upon the surface. The osprey has often to plunge

beneath the water in the pursuit, and Nature has gifted him with power

to do so, which, if I am not mistaken, she has denied to the eagles. The

latter are therefore compelled, in some measure, to depend upon the

former for a supply. But the eagles sometimes do catch the fish

themselves, when the water is sufficiently shallow, or when their prey

comes near enough to the surface to enable them to seize it.”

“Do they ever kill the ospreys?” inquired François.

“I think not,” replied Lucien; “that would be ‘killing

the goose,’ etcetera. They know the value of their tax-payers too well

to get rid of them in that way. A band of ospreys, in a place where

there happens to be many of them together, have been known to unite and

drive the eagles off. That, I suppose, must be looked upon in the light

of a successful revolution.”

The conversation was here interrupted by another

incident. The ospreys had again gone out fishing, and, at this moment,

one of them was seen to pounce down and take a fish from the water. It

was a large fish, and, as the bird flew heavily upward, the eagle again

left its perch, and gave chase. This time the osprey was overtaken

before it had got two hundred yards into the air, and seeing it was no

use attempting to carry off the prey, it opened its claws and let it

drop. The eagle turned suddenly, poised himself a moment, and then shot

after the falling fish. Before the latter had got near the ground, he

overtook and secured it in his talons. Then, arresting his own flight by

the sudden spread of his tail, he winged his way silently across the

river, and disappeared among the trees upon the opposite side. The

osprey, taking the thing as a matter of course, again descended to the

proper elevation, and betook himself to his work. Perhaps he grinned a

little like many another royal tax-payer, but he knew the tax had to be

paid all the same, and he said nothing.

An incident soon after occurred that astonished and

puzzled our party not a little. The female osprey, that all this time

seemed to have had but poor success in her fishing, was now seen to

descend with a rush, and plunge deeply into the wave. The spray rose in

a little cloud over the spot, and all sat watching with eager eyes to

witness the result. What was their astonishment when, after waiting many

seconds, the bird still remained under water! Minutes passed, and still

she did not come up. She came up no more! The foam she had made in her

descent floated away—the bosom of the water was smooth as glass—not a

ripple disturbed its surface. They could have seen the smallest object

for a hundred yards or more around the spot where she had disappeared.

It was impossible she could have emerged without them seeing her. Where,

then, had she gone? This, as I have said, puzzled the whole party; and

formed a subject of conjecture and conversation for the rest of that

day, and also upon the next. Even Lucien was unable to solve the

mystery. It was a point in the natural history of the osprey unknown to

him. Could she have drowned herself? Had some great fish, the “gar

pike,” or some such creature, got hold of and swallowed her? Had she

dashed her head against a rock, or become entangled in weeds at the

bottom of the river?

All these questions were put, and various solutions of

the problem were offered. The true one was not thought of, until

accident revealed it. It was Saturday when the incident occurred. The

party, of course, remained all next day at the place. They heard almost

continually the cry of the bereaved bird, who most likely knew no more

than they what had become of his mate. On Monday our travellers

re-embarked and continued down-stream. About a mile below, as they were

paddling along, their attention was drawn to a singular object floating

upon the water. They brought the canoe alongside it. It was a large

fish, a sturgeon, floating dead, with a bird beside it, also dead! On

turning both over, what was their astonishment to see that the talons of

the bird were firmly fixed in the back of the fish! It was the female

osprey! This explained all. She had struck a fish too heavy for her

strength, and being unable to clear her claws again, had been drawn

under the water and had perished along with her victim! |