|

IT was in the Spring of the eighth year following the

founding of our settlement that certain events took place, each of which

was to have an influence on my life. I was nineteen years of age at this

time, and known throughout the community as Big John Wallace. I stood

six feet three inches and weighed —according to stillards at Shooper’s

Wharf, at which a schooner, owned and captained by one of that name,

touched monthly during the Summer—two hundred and twenty pounds.

Needless to say, my great size was a source of constant mortification to

me. The lads of my own age joked me about my huge hands and feet, and

the girls at the dances looked startled if I requested them to honor me.

I think I must have been very good-natured, because neither teasing nor

jeers seemed to affect me. I was fond of music and loved dancing, and

thanks to my father’s training—in Scotland he had held the county

championship for running, jumping, wrestling and boxing—I got through it

well in spite of my size.

Let me say just here that two years previous to this

happening I am about to relate, an English sportsman of independent

means and, I understand, of blue blood, had purchased a large section of

prime forest from the government, at a point some forty miles east of

us, on the shore of the lake. His name was Hallibut. He was of

autocratic and overbearing manner, fond of his drink and a true lover of

the hunt. With him he had brought a number of dissolute companions, most

of them, like himself, scions of noble family.

Colonel Hallibut’s house, the first to be built of

lumber, he having brought a portable sawmill into the forest with him,

was a big, rambling structure, erected to stand the stress and wear of

the elements. All about it he had built a wall of oaken timbers, why, I

cannot say, unless indeed it was because he feared an attack by the

Indians, whose rights he had in a measure usurped in taking from them

their best trapping grounds. Within the stockade were huge kennels for

dogs, of which he kept a great many, some of them big, ferocious brutes.

Too, he owned horses, it was said, of thoroughbred Arabian strain, also

guns of newest pattern.

Many stories had come down to us of wild carousals held

in the big white house and certain lawless depredations committed by the

men who enjoyed the freedom of the Englishman’s home, and of one of the

latter it is my wish to speak particularly now.

This man, whom I had never seen, was known as Gypsy Dan.

Why he was so called I cannot say, unless it be on account of his

eccentricity in dress and a penchant for living in the open; certain it

is he had no Zingarioan blood in his veins. This man, we had learned,

acted as scout to Hallibut, that is to say, he and a number of wild

fellows under him roamed the forest and located the game which Hallibut

and his ilk later followed and killed.

On several occasions we had found our crops trampled and

destroyed; our fences tom down, and calves, sheep and cattle missing.

More, we had lost hams and shoulders from our smokehouses; but never had

we been able to glimpse Gypsy Dan at close range. Needless to say, then,

not one of us, hard-working, law-abiding and God-fearing as we were,

bore this man any great love. So it was, that when he came unexpectedly

and fearlessly among us—as I am about to relate—you can understand why

he was given no friendly welcome.

There had been a logging bee at Sandy Jamieson’s place,

at which the best men and the best oxen in the community had striven in

competition. Red McDonald’s span of roans, “Buck” and “Bright,” had

proved their supremacy over “Bill” and “Tom,” Neil Cameron’s span of

blacks, and McDonald was happy as a result. His voice boomed out in

laughing jibe at his vanquished neighbour, and from one end of the long

supper table to the other, men with sun-blistered faces and brown arms

laughed at his witty sallies.

Neil Cameron sat silent, eating heartily, and paying no

attention to his neighbour’s witticisms. It was a well-known fact

amongst us that he and Red McDonald were rivals in clearing, tilling and

saving. Both had done well during the eight years they had striven side

by side. Cameron’s stumpy fields were many; his crops were clean and his

harvests, bushel for bushel, as great as Red McDonald’s; as was also the

amount of money he had put by each year through disposal of his surplus

grain and roots. Like McDonald, Cameron was a fair and just man,

hospitable as all Scotchmen are, and close-fisted when it came to a

deal. They were good friends, too, in spite of the thrift-fence between

them, those two with hair now turning grey on the temples and faces more

deeply lined than when they caught first glimpse of the forest they were

subduing.

“Ho, Neil Cameron"” called little Pat O’Doone, who never

worked, but was always invited to bee or raising because he could play,

the fiddle, and possessed a pretty daughter, who was the best dancer in

the community. “Look down your long nose, man, and see if you can’t find

a smile.”

Cameron laughed then. Nobody could withstand the

Irishman’s droll humor.

“Red Mack's Buck and Bright are too big-boned and strong

for your game little yoke of Blacks, Neil,” said Sandy Jamieson.

“Bone and muscle don’t always count,” spoke up a jeering

voice, and turning I saw a stranger standing just behind O'Doone; a

tall, well-formed fellow with swarthy face and clustering dark hair

falling to his shoulders. He wore a jacket of scarlet and in his ears

were rings of yellow metal. My first impression of him was not pleasant.

All eye3 had turned upon the stranger who stood there,

his arms folded across his breast, a half amused smile on his thin lips,

returning the surprised looks of the farmers contemptuously.

“Who are you, Man?” asked Red McDonald, rising from the

table, “and what do you want here?”

The other was slow to answer. He had turned his head

slightly, and now his eyes were fixed on the face of Flora McDonald, who

was helping to wait at table, and had just come up with a platter of hot

biscuits.

I saw her start, saw her eyes lift to the stranger’s; saw

the color dye her cheeks before his stare.

Bob McDonald and Jack Cameron, who were one on either

side of me at table, half rose from their seats. I, too, stood up. There

was a queer, tightening sensation in my muscles, a quivering and

pricking of my skin, like a dog whose hackles rise at sight of a wolf.

The feeling was new to me.

Red McDonald stood now confronting Gypsy Dan, for he I

knew it surely was, from the description which had been given me.

“You’re not wanted here,” McDonald addresed him sternly,

“so begone!”

The man showed his white teeth in a sneer, and placing

his fingers in his lips, blew a shrill whistle.

Almost immediately from the trees about the cabin sprang

a number of wild-eyed men, dressed as grotesquely as their leader, and

ranged themselves beside him.

There were some ten or more of them, all armed with

flintlock muskets and carrying knives in their belts.

A tense silence had fallen. The men at the table stared

stupidly up at Red McDonald and the unwelcome strangers, paralyzed, I

suppose, at the suddenness and unexpectedness of the thing.

Gypsy Dan was smiling.

“Easy, my good fellow,” he addressed Red Mack, “and a

little more courtesy, if you please.”

McDonald stood, his face set, his hands clenched. Once he

made as though to rush in and strike that smiling face, but the men who

had ranged themselves beside their leader lifted their muskets, and he

held himself in check.

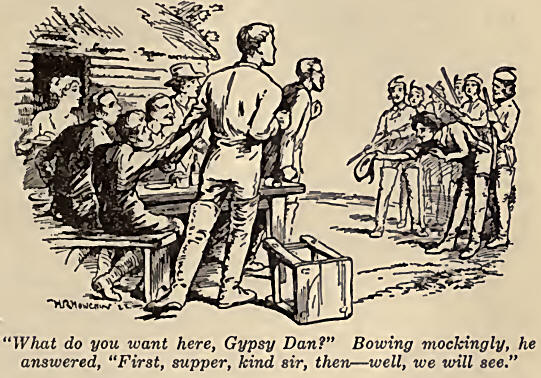

“What do you want here, Gypsy Dan?” he asked again.

The fellow swept his plumed hat from his head and bowed

mockingly.

“First, supper, kind sir,” he answered. “Then—well, we

will see. Perhaps I shall claim a kiss from ” and he motioned toward

Flora McDonald, who stood wide-eyed, watching and listening.

I went up to him then, brushing aside my friends who

attempted to stay me, and, catching hold of his arm as his hand swept

downward toward his knife, I twisted it sharply, so that he cried out in

sudden pain. Then lifting him, I hurled him among his fellows, sending

them rolling like so many nine-pins.

This was the signal for general action. There was a rush

of feet, a hoarse, jumbled cry of angry voices, and the men of the

Settlement, seizing handspike, axe or whatever weapon was handy, rushed

forward.

But Red McDonald's voice thundered out in command.

“Back, men, back! They are armed and will kill you. See,

they are moving off! Let them go, we want no bloodshed here.”

True enough, Gypsy Dan and his followers were vanishing

among the trees.

Jack Cameron had gone across to Flora McDonald. His hands

held hers as though in silent assurance that she would never need for a

protector. As for me, I thought with a pain in my heart of how perfectly

those two, promised to one another, were mated.

By and by we sat down at table again. But it was a silent

meal. Gone was the banter and chatter, gone the laughter from Red

McDonald’s voice when he turned toward Neil Cameron and spoke.

“Neil Cameron, as Satan entered Eden, so has lawlessness

come into our community. My oxen will continue to outhaul yours, if so I

can make them, my land yield greater crops, and my money box outweigh

your own. But when comes a time of common menace to our peace and

lives—as now—how about it, Neil Cameron?”

And Cameron, shaking back his grizzled locks, answered.

“I am a better farmer than you, Red McDonald; a

thriftier, too, which I shall continue to prove. But because I am Scotch

and, I hope, a man I’ll stand shoulder to shoulder with you against a

common foe, as we stood shoulder, to shoulder at Balaclava, and fought

to the urge of the pipes; and God help those who come against us.” |