|

I WAS spared the sin of lying to save the man into whose

keeping sweet Flora had given her heart; and it was in this way;

After parting with Flora I had gone directly home, not

feeling equal to mixing with the neighbours and fearing lest in my

clumsy way I might let fall some word which might incriminate Gypsy Dan.

I was sitting in the darkness of my cabin when Jack

Cameron stumbled into the room. I spoke to him, but he gave me no

answer. I heard him draw out a stool and sit down. I got up then and lit

a candle.

Jack sat by the table, his arms thrown across it, and his

face upon them. I placed my hand on his shoulder, and I felt him shudder

at my touch. x “Jack,” I asked, “what is it?”

He raised his head then, and I shall never forget the

stricken look on his white face. “God! John,” he shivered, “what am I to

do? Tell me, what am I to do ?”

I shook him roughly. “Come,” I said, “do not speak in

riddles. What do you mean?”

He got up from his stool, slowly, and stood looking into

space. I lost patience then.

“Jack Cameron,” I cried, “tell me, what is wrong with

you?” A hand went gropingly into his pocket. When he withdrew it, he

held out an object to my view. It was Neil Cameron’s pipe, one which

Sturgeon, the Indian Chief, had carved and given him. I recognized it at

once. ’

“I found this beside the burnt stacks, John,” he said

miserably.

At once my mind flashed to the quarrel between Red

McDonald and Neil Cameron, when Cameron had uttered a threat against his

neighbour. I took the pipe from Jack’s hand.

“Does Red McDonald know?” I questioned.

He nodded miserably. “He was with me when I found the

pipe. He went straight to father. I went with him. He accused father,

and ” His voice broke. “Father didn’t deny it!”

At his words I felt a faintnes assail me. In the face of

what I now knew, I could not but believe that Cameron had fired the

stacks; and yet, the heart within refused to accept the fact.

So there I stood like a big, slow-witted yokel I was,

while common-sense and that strange loyalty one Highlander holds for

another fought it out between them.

As I turned toward Jack, he gave a long, gasping sigh,

almost a sob, and for the second time I experienced that icy clutch at

my heart. It angered me.

I grasped him roughly by the shoulders and swung him

about. “Stop that sniffling,” I cried, “and, for God’s sake, try to pull

yourself together. What does Red McDonald intend to do?”

“Nothing,” he answered, dully; “that is, no more than he

has already done.”

“And what is that?” I asked.

He made a gesture of hopelessness. Knowing the fiery

temper of Red McDonald, I could guess what he had done. He had cursed

Neil Cameron and all his kin. Jack Cameron’s hope of ever marrying sweet

Flora McDonald was as broken as a sapless reed in the gale.

Jack was groping his way toward the door. I placed my

hand on his arm, but he jerked himself free and stamped out into the

night.

I closed the door, and lighting the fire, prepared my

supper. After I had eaten, I blew out the candle and sat in the

darkness, trying to ponder it all out.

Snarl, the wolf-dog, lay at my feet. Through the darkness

his coal-eyes gleamed up unblinkingly into mine, sensing, as he did, the

unrest which had come to me, and with his dog’s love accepting the

burden as part of his own. And the hours passed and the fire burned to

grey ash on the hearth, and as I sat there motionless, reviewing the

strange happenings which had crowded themselves into the past day, he

did not stir; nor did the watching understanding eye of him leave my

face.

* * *

I have always been given to understand that the wits of

men of unusual size are not so bright as those of their smaller fellows.

Whether or not this be true, I do not know. All I know is that my own

wits must have been dull indeed, otherwise, I would have been in a

measure prepared for some of the events which occurred during the

coldest and fiercest winter that I have ever in my long life

experienced,

I had not seen Jack Cameron since that night he had

walked out of my cabin, and I missed his bright companionship sorely.

From Pat O’Doone, who acted as Settlement news-carrier, I learned that

he was living with Trapper Jake Hood, on the Point.

“Poor bye,” said Pat, “it’s dhrinkin’ like a fish he is,

and creepin’ like a blind mole into the trap av that cunnin’ devil.

Shure he’s under the spell av that witch Nance’s smoile. Some day the

money Neil Cameron has worked so hard to git ’ll be goin’ to Jack; and

marrak me wurrids, it’ll be Hood who’ll be spindin’ it.”

I tried to make light of the Irishman’s prophecy; but I

must confess his words troubled me. I made up my mind to go and fetch

Jack Cameron home. If he didn’t come willing, I would drag him, and

heaven help Hood if he interfered.

But owing to the arrival of the threshing outfit and the

repairing_of the shelter sheds for the cattle and sheep, after my grain

was safe away in the granary, the fierce winter was upon us before I

found myself free to act.

Then came a blizzard which lasted for four days, and when

the skies cleared, the snow lay level with my cabin windows.

Fortunately, my stock had not suffered, for acting on old

Injun Noaha’s advice—he having foretold the coming of the great storm—I

had left both cattle and sheep loose in their sheds, with corn fodder

and straw aplenty for their needs. Nevertheless, I found the cattle

badly in need of water. Neil Cameron, I learned, had lost six head of

steers and two milk cows through exposure, and many other of the

neighbours had suffered even more.

The weather, following the clearing of the skies, had

grown so cold that the hearts of great trees split with the frost, and

the ice on the bay cracked like the report of a cannon. However, cold

could not daunt me, and .as I donned my warmest coat and examined my

snow-shoes, the while Snarl eyed me intently, wagging his bushy tail in

appreciation, I found myself whistling blithely. I was glad I was going

to have action, too much of it for my comfort, perhaps, but I wasn’t

caring. Jack Cameron was coming home with me.

As I lifted .down my musket from its rack, a knock fell

on the door.

“Come,” I invited.

The door opened and Tom Bandy, the inn-keeper, and a

stranger, both wearing fur coats, entered.

“I put my horse in your stable, John,” accosted Bandy.

“Must be fifteen below zero this morning; the sled shoes fairly freeze

to the snow. This here gent with me,” he added, “is Mr. Stilwell, a

fur-buyer from Montreal. He heard you had some pelts for sale, so I

drove him over.”

“Well,” I replied, “I guess you’ve had your drive for

nothing. I haven’t any furs for sale. I had a few, but they were stolen

a couple of weeks ago.

“Now, that’s too bad,” spoke up Stilwell. He unbuttoned

his coat and produced his pipe. “Any idea who took ’em?”

I shook my head.

He puffed at his pipe and, having gotten it going to his

satisfaction, unbuttoned his inner coat and vest.

“I’m going to show you a skin that is a skin,” he

declared. “I bought this pelt from trapper Hood the day the blizzard

struck this place.”

I stood there staring. He was holding a silver-grey fox

skin up to view.

“Isn’t it a beauty?” he exulted. “Look at those

guard-hairs; they’ll fairly drop of their own weight.”

I took the pelt from him and carried it to the window. In

the broader light I examined it. Just behind the ears were two tiny

perforations where buckshot had entered. There was no mistaking the fact

that I held in my hand the priceless fox skin which had been stolen from

me.

“You say you bought this pelt from Hood?” I asked.

He nodded. “Three hundred I paid that rogue for it, my

boy,” he laughed.

“It’s worth a thousand,” grumbled Bandy, sourly.

Stilwell winked at me.

“Bandy knows Hood will spend what he got for this pelt at

his bar,” he chuckled, “and he’s sore it isn’t more.”

He took the skin from my hand and replaced it within his

vest.

“Too valuable to leave carelessly about,” he explained,

“that’s why I carry it with me.”

I nodded, scarcely hearing. My own thoughts were keeping

me occupied. It was clear to me that Hood had stolen my pelts and money.

Hood would settle in full with me.

* Tom Bandy was standing watching me, a queer smile on

his weasel face.

“Heard about your friend Jack Cameron’s latest doin’s?”

he asked, as he pulled on his mittens.

"Well, he’s up and married old Hood’s wench, Nance,” he

grinned. "Reckon Neil Cameron’ll wish he’d not been so hard on the boy

now.”

I stood there too stupefied to answer, while he and

Stilwell passed out into the crisp, cold day. Jack Cameron married to

trapper Hood’s Nance! I could not believe it.

* * *

Two hours later I left the frozen bay and entered the

pine forest of the Point. Straight up through the spicy gloom I raced

until I reached a slashing in which rested a long low cabin of logs.

Smoke ascended from its squat chimney, a grey unwavering

line against the cold sky. As I kicked off my snow-shoes and strode to

the door, a pair of fierce curs bounded to meet me with neck heckles

raised and jaws adrool.

With a kick I sent the larger of the two howling among

the underbrush. Snarl had promptly closed with the other. As I reached

for the wooden latch, the door opened and trapper Tom Hood stood before

me.

I pushed him back into the cabin and followed him. Jack

Cameron lay on a bunk, a bottle of whiskey beside him, and Nance stood

beside the fireplace stirring something in a pot.

I could see that Jack was half drunk. He raised himself

on his elbow as he caught sight of me, then promptly fell back and

turned his face away. Nance stood staring insolently. It was Hood who

broke the tense silence of the moment.

"Why,” he cried, making a poor attempt at friendliness,

"it’s Big John! Wants to ask some more questions about trappin’, I’ll

wager!”

"Some questions, yes,” I returned, " but not about

trapping.”

"Why then, be seated,” cried Hood, ill at ease, as I

could see.

"Hood,” I said, coming straight to the point, "you stole

my furs and fifty dollars of my money. You sold the pelts to Stilwell.

Now, I want the money he paid you for them and the fifty you took from

my cabin.”

He fell back from me, his face working and his lips drawn

back from his uneven teeth in the snarl of a baited bulldog.

One hand swept the cluttered table and closed over the

handle of a thin carving-knife.

Jack Cameron sat up in his bunk, his blood-shot eyes

taking in the situation.

"Here, Tom, none of that!” he cried, and sprang straight

out at Hood.

The trapper’s arm rose and fell and Jack sank to the

floor with a groan.

Before Hood could move again I had him. My arm about his

throat; I tightened my clutch, bending him backward across my knee. At

the same time I twisted the wrist holding the knife until I heard the

bones grate. Then I flung him against the wall, where he hung for a

moment before sprawling senseless.

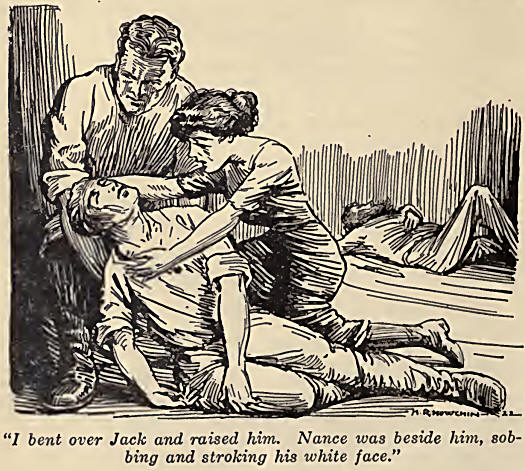

I bent over Jack and raised him. Nance was beside him,

sobbing and stroking his white face. Quickly I sought for the wound and

was relieved to find it no more than a deep cut in the fleshy part of

his shoulder. I lifted him to the bunk and ordered Nance to heat water

and bathe the wound. Then I gave my attention to Hood.

He opened his eyes as I bent over him, and if ever I saw

fear in a man’s face, it was in his. I picked him up and placed him on a

chair. He lifted his maimed wrist, and in his eyes was the look of a

trapped wild thing. Pain had bleached his tanned skin and beads of sweat

glinted on his chin and forehead.

“You devil!” he gritted, “you’ve broken my arm; damn you

to hell, you’ve broken it.”

“Listen, Hood,” I said, “it isn’t half what I intend

doing to you unless you do as I say. I want the money you stole and what

was paid you for my pelts.”

His head sagged. “Give it him, Nance,” he said, weakly.

Nance lifted a skin curtain and drew out a canvas shot

sack, which she tossed to me.

“Take what is due you from that,” said Hood. “I got

$400.00 for the pelts.”

I took this amount, plus fifty dollars, from the sack and

threw the sack on the table.

Then I gripped the swollen wrist, which Hood was nursing

tenderly. He uttered a sharp cry of agony as by a quick wrench I drew

the displaced bones into their sockets.

“You’ll be all right soon,” I told him. I pointed to

Jack, who was now conscious. “What if you had killed him?” I asked.

He shuddered and sank deeper in his chair.

“Hood,” I said, “I’m going to have a look in your

root-house, and you’re coming with me. I’ve an idea that you’re the

thief who has been robbing the Settlement smoke-houses.”

“It’s a lie!” he cried, springing to his feet.

Nance, who was kneeling beside Jack Cameron, sprang up

and confronted him. Pointing an accusing finger at him, she

cried: “It’s not a lie, Dad, and you know it! And

there’s

another thing he did,” she cried, turning to me. “He

fired McDonald’s grain stacks, hoping to place the blame on Gypsy Dan.

He hates Gypsy Dan for driving him out of old Hallibut’s

trap-ping-grounds.”

“You—you-” commenced Hood, but passion choked his

utterance.

“You would have killed my husband,” the girl addressed

her father. “I have stood a lot from you, Dad, but this was too much.

Not content with making him the drunkard he is now, and doing your

utmost to destroy his manhood and his trust in his friends, you tried to

murder him. I am through with you. I have to choose between you, and

Dad—I love him best.” Hood’s head sagged on his breast. It was a hard

blow, this mandate his daughter had delivered.

“Hood,” I asked, lifting the chin of the grovelling creature

before me with no gentle hand, “is what your daughter says, true?”

He nodded.

“Then,” I said, “you’re worse than a thief and a would-be

murderer; for by your lawless act of firing McDonald’s stacks, you have

made two life-long friends enemies, and Jack Cameron, there, the wreck

you see him now.”

I lifted down his coat and cap from a peg. “Put those on,

and come with me,” I commanded.

“Where?” he gasped.

“To Red McDonald and Neil Cameron,” I cried sternly, “so

they may hear with their own ears that you have confessed to me.”

“I’ll not go,” he snarled. “They’ll put the law on me.

I’ll be jailed.”

“You’ll come,” I told him, “if I have to drag you!”

Nance laid her hand on my arm. “John,” she pleaded,

“won’t you for Jack’s sake and mine, let him go? He will slip away and

never come again to this place. I will go with you to Neil Cameron and

Red McDonald and tell them all.”

Jack Cameron, now conscious and sobered by what had taken

place, sat weakly up on the bunk.

“Nance’s plan is best, John,” he urged. “Hood’s flight

will be construed as proof of his guilt. Accustomed as he has been to

the out-of-doors, imprisonment would surely kill him.”

“And he deserves it!” I cried; but in my heart, because I

knew the power of the tangled, spicy sweeps, I knew I would never hand

this guilty man over to the law.

“Give me another chance,” pleaded Hood. “I’ll leave at

once, and I swear never to return.”

“Then listen to me,” I cried. “You will have your chance,

Hood. But as true as God is above you, if ever you come back to this

place, you’ll be punished for your crimes, and that I promise you.”

I took the money I had extracted from the shot-bag from

my pocket and put it in his hand.

He stared at me dumbly and attempted to speak, but I

motioned to his coat lying across a chair.

“Go now,” I said. “If by to-night you are not far on your

way, I would give little for your chance of freedom.”

He shook himself then and pulled on his skin coat. Nance

came out of the shadows and stood before him.

“Dad/’ she whispered, “I’m sorry—but you would have

killed the man I love.”

He drew her to him and held her close. The tears stood in

his eyes. I believe the one green spot in his blackened soul was his

love for this motherless girl.

Nance went back, sobbing softly, to where Jack Cameron

sat. He put his arm about her shoulders.

I spoke to Hood.

“If in that place you now seek, you live a clean life,

she will forgive you,” I said.

He looked up miserably and shook his head.

“She has lost all faith in me,” he groaned, “and it is no

wonder.”

I turned to Nance. She had heard what I said to her

father, and now hovered near like a wild bird that has been fettered and

glimpses sunlight and freedom.

“Oh, Dad,” she cried eagerly, “what Big John says is

true! It is your chance. Take it!”

“I will,” he murmured. Then, lifting his head, he said

earnestly, “I am going now to make a new start. When I am sure of

myself, I’ll let you know, Nance.”

He strode over to Jack Cameron and held out his hand.

“Jack,” he said, “I was crazed with drink and fear. Will

you forget it?”

Cameron stood up and gripped the hand of his

father-in-law.

Then, without another word, Hood picked up his rifle and

went out into the cold, blue day. |