|

WHAT a wonderful thing is true friendship, but a still

more wonderful thing, I think, is a friendship that has been broken and

welded again.

For years the people of the Settlement spoke of the grand

reunion of the Camerons and McDonalds, the feast and the dance which

followed the gripping of hands between Red McDonald and Neil Cameron

when the true facts concerning the burning of the wheat stacks became

known.

I can see them yet, these two gaunt men, seated side by

side beside the ruddy fire, the light of true understanding in their

seamed faces and the spirit of happiness stirring their hearts to song

and mirth, the while the younger folk danced and made merry in the

great, brown-raftered room.

Flora McDonald was here and there like a fairy, chatting

with this one, laughing with that and dancing with still another.

Fiddler O’Doone, at his best, played reel and cotillion with a power

sufficient to make the staidest set of toes itch to tap the floor,

opening his eyes only at the end of the set to peer about for the squat

demijohn from which he derived his inspiration.

Kathie O’Doone and Bob McDonald danced much together that

night, and even I, stupid about such things as I was, sensed something

more than mere friendship in the manner they held together.

One event of that night stands out very clearly in my

memory. It was the dancing of the “Scotch Four” by Anne McDonald, Neil

Cameron, Flora McDonald and myself, to the sweet music of the pipes

played by Red McDonald. Always to me, who could scarcely play even three

bars on the jewsharp without discord, and was never allowed to sing in

chorus on account of my bellow drowning the voices of the other singers,

music has had the power to draw me back to those things sweetest and

most tender in life; and this night, as the pipes called and my soul

answered, the big room with its shadow-painted walls faded back—and in

its place was the sward of my native hills, soft in the moonlight; the

spice of the mountain craigs and forest was in my mouth, and the daring

of youth which trusts aljl things was in my heart, while near me hovered

the sweet Flora McDonald of yesterday, grey-eyed and tender as in those

days before the realization had come to me that she must leave me.

Never before had I seen her so beautiful. In her face was

the rapt look of one who dreams, and while the casual looker-on might

think her smile and merry quip was for me alone, I knew better. Dull as

I was, I sensed in her that intoxicating spirit of daring and adventure

which bids the lured one seek new paths for old; and I knew that soon

she would go out from my life and I must face the trail alone. God help

me, that time was closer at hand than I thought.

I say we danced the dance of our home hills that night,

and when it was done, with a dewy tenderness shining in her eyes, she

beckoned to me, and led the way out into the dark, spacious store-room.

“John,” she whispered when we were alone, “he was here

to-day.”

“Yes?” I answered, knowing too well to whom she referred.

“He talked with father, John.”

I waited to hear more. It was too dark to see her face,

but I knew from the tremor in her voice that tears stood in her eyes.

“Father sent for me after he had gone,” she faltered. “He

says I must never see Dan again.”

I sought her hand and held it close in mine. “And your

mother?” I questioned, “what did she say, Flora?”

“Mother would have me do even as she herself did,” she

answered, “marry the man I love.”

“In spite of what your father commands?” I asked.

She was silent, but I felt her form tremble.

“John,” she almost choked, “some day you will love, and

then you will understand that there can be no obstacle to that you

desire.”

Great God, if she could have but read my heart!

I could not speak to her. My veins were frozen; my heart

and voice numb with the pain her words has so unwittingly brought.

Neil Cameron’s voice was heard calling lustily.

“John, Flora, come! Supper is waiting and we are

languishing for food.”

He came striding into the store-room, laughing happily as

a boy.

“There was something more I wished to tell you, John,”

Flora whispered as we followed Neil into the dining-room.

In my soul I was glad that Neil Cameron had come when he

did. I was beginning to be afraid of myself. I was but flesh and blood

after all.

I did not see Flora alone again that night. Others

claimed her. She fluttered like a butterfly among her guests.

I went home early. Strangely, the realization of the

unutterable loss I was about to suffer—aye, was already suffering

—struck me this night more forcibly than ever before.

In the darkness of my cabin I sat down with my misery;

the dog, Snarl, beside me, his head on my knee.

It was in the chill, drab dawn of a wintery morning when

a knock on my cabin door stirred me from a half sleeping stupor. Snarl

raised his heavy head and whined. I knew then who stood without, and for

a moment, numbed by the chill that had crept into me, I was powerless to

rise; then the conflicting emotions that swept hotly through me at the

knowledge of sweet Flora's nearness, dispelled the numbness which bound

me and, springing up, I threw open the door.

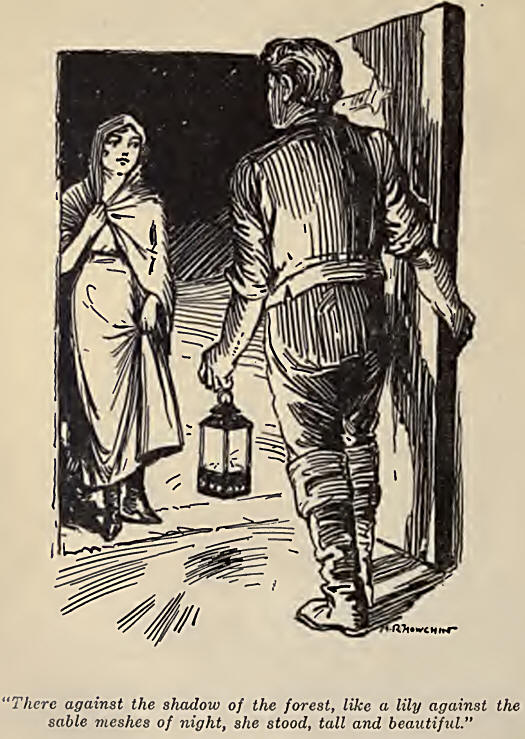

There against the shadow of the forest, like a lily

against the sable meshes of night, she stood, tall and beautiful. The

light of love and happiness was in her face, and in the clustering

ringlets that framed it was dawn’s pale sheen and sunset’s russet gold.

“John,” she faltered, “dear John.”

“Flora,” I cried, taking her wee, cold hands in mine,

“what is wrong? Why are you here and dressed as though for a journey?”

She pointed toward the dim corduroy; and then it was I

discerned waiting in the edge of the grove, a man on horseback. Another

saddled horse was beside him.

“Flora,” I said, drawing her into the room, “you are not

running away?”

She nodded, laughing happily; for love, like the warmth

of spring, knows only its own fire and power and sees naught of the

frozen banks between which it melts its way.

“With him, Flora?” I asked.

“Yes, Big John,” she answered softly. “I love him. You

would have me happy, wouldn’t you, John.”

“God knows I would,” I answered, “and that is why I fear

the consequences of this rash thing you are doing, Flora.”

“There is no other way, Big John,” she sighed. “You know

my father. He would never consent to my marrying Dan. By and by, when he

learns to know how he has misjudged him, he will forgive.”

I stood there gazing down on her dear face. There was no

conflict within me; only a doubt, grim and sharp-taloned, ripped my

soul. I loved Flora McDonald, had loved her always. But never during

those wilderness years when our paths ran parallel had I for one moment

forgotten that she was of the Clan McDonald and I but the servant of her

pe6ple. And I had told myself that some day she must go out from me as

she was going now.

“Wait you here a moment,” I said almost gruffly, and

turned to the door.

“John,” she whispered agonizingly, “you will not hurt

him?” I shook my head, unable to trust my voice, and striding out, went

down to where Gypsy Dan waited in the shadow of the elms. He saw me

coming and dismounted. He was standing there slender and graceful when I

came up to him.

For a long moment we looked into each other’s eyes. Then

he spoke. “John,” he said earnestly, “I love her. You may set your fears

at rest.”

“Gypsy Dan,” I answered him, “God help you if you harm

her in any way, for if you do, I shall seek you out and tear you limb

from limb.”

At my words a look of surprise and pity came into his

handsome face. He reached out a hand and laid it on my arm.

I shook it off angrily.

“John,” he said gently, “I didn’t know it was like this;

you’re a real man, by God!”

I turned fiercely upon him. “She must never guess" I

commenced, but his grip on my hand told me he understood.

I took a strong hold on myself and faced him. “Where do

you go?” I asked.

“To St. Tobias,” he answered. “The circuit minister is

there waiting.”

“Then,” I said, “I go with you.”

He stared at me. “Surely you trust me now, John,” he

said. “I swear ”

“It is not that I do not trust you,” I told him, “but it

is her great day, and I would be there to see it dawn for her and wish

her happiness.”

“But Red McDonald will think perhaps that you abetted

us,” he protested, “I would not have him misjudge you.”

“Let him think as he will,” I flung back, “I am going

with you.”

So it was that we three rode away down the dim trail

together toward the lifting dawn. The horse I bestrode was a powerful

roan which I had recently purchased from a dealer who was glad to let

him go on account of his vicious temper. The slender-legged mounts of

Flora and Dan—two from Hallibut’s string of thoroughbreds, I knew them

to be—minced their way through the silent-sheeted forest, paying not the

slightest heed to my stallion’s snorted threats and evil rolling of eye.

And as I watched those twain who rode before me, young, handsome, each

with the poise that is born of blue blood, my heart sunk like lead in my

breast and a mist came to my eyes.

But, like one who follows the bier of one long loved and

soon forever lost, I followed Flora and Gypsy Dan. It was my hour. She

was still mine until the law of God made her another’s.

The light of morning grew up and painted the dead forest

with glories. Their happy voices came back to me; but I rode with head

bowed and chin on my breast.

* * *

At noon I returned to the Settlement. Red McDonald was

waiting for me in my cabin. He got up from his chair as I entered, and

the look in his face smote me. He had aged greatly during the past few

weeks. I had expected a stormy time with him, and was unprepared for

what he now did.

“John,” he said brokenly, “is this thing that Anne tells

me true? Has Flora gone with with?”

“It is true,” I answered. “They were married this morning

by the preacher, Lloyd, at St. Tobias.”

He rasied his eyes, and there was a dazed, hurt look in

them. “She disobeyed me, John,” he said, and his voice quavered. “Sweet

and obedient as she has always been, she disobeyed me in this thing.”

“It broke her heart to be obliged to do it,” I answered.

“Aye,” he nodded, “I can understand that. But, John, the fact stands

that she went against the wishes of her father. She is no longer

daughter of mine, John.”

“Then, Red McDonald,” I cried, banging my first on the

table so that the cabin shook with the impact, “I am no longer your

friend and neighbour!”

“Tut, tut!” he exclaimed, “surely you would not turn

against me, Big John?”

“Flora has not turned against you,” I told him, “and you

know it. She has married the man she loves. Would you have her do

otherwise?”

“Her first duty was to me,” he said doggedly.

“Supposing,” I said, “the girl Anne whom you wooed and

won in the Highlands, had told you that her first duty was to the father

*who refused you her hand? What about it, Red McDonald?”

His big head drooped. “Then,” he said brokenly, “I must

have lost a great deal, John.”

He was silent for a long time, and I did not interrupt

his thoughts.

When he looked up his eyes were misty.

“Big John,” he said, “will you go and bring them home?”

“Gladly,” I answered.

Just here a voice raised in profanity mingled with the

growling of dogs sounded without.

I opened the door. Seated astride a beautiful black horse

was a big man whom I guessed at once to be the eccentric Englishman,

Colonel Hallibut. Half a dozen lean dogs frisked about his horse’s

heels, baying and snarling and behaving as dogs will after loosed from

confinement.

“Hullo!” exclaimed the rider, catching sight of me.

“Young man, will you oblige me by taking your gun and shooting every

damned dog in this pack?”

He leaned over and brought his heavy quirt down close

beside an angry hound. The dog whined, and leaping up, left a damp

caress on the hand that was doubled on the whip.

“Curse me!” exploded the man, “they’ll be the death of me

yet, those dogs.”

“They don’t appear to be greatly frightened at you, at

any rate, sir,” I said, coming forward.

A smile lit up his coarse, red face. '

“I’m afraid I spoil the devils,” he confessed. They know

I love ’em, and they take advantage of it.”

I ran my eye over the dogs. I was glad that Snarl was

safely shut in the stable. He would be gazing through a chink in the

logs, I knew, voiceless and tense, and eager to resent the coming of

these strangers into his realm.

“I’m Hallibut,” my visitor informed me, “and from your

looks, I take you to be this Big John Wallace I’ve been hearing about.”

I bowed.

“I was told that Red McDonald was here,” he went on. “May

I have a word or two with that gent?”

“He’s inside,” I answered.

The Colonel dismounted, puffing and rubbing his stiffened

joints; for he was no longer a young man, and high living had given his

great frame too much weight.

He went inside and I led his horse to the stable.

When I returned to the cabin, Colonel Hallibut and Red

McDonald were seated opposite each other at table. I could see at a

glance that McDonald was greatly interested in what our visitor was

telling him.

“This chap known to you as Gypsy Dan,” Hallibut was

saying, “is my nephew. His true name is Dan Whitelaw. He comes from good

English stock, and in spite of the fact that I’ve done my best to spoil

him, the young beggar’s got a lot of good in him. I’m glad he married

your daughter, McDonald. It’ll be the making of the boy.

“Now,” he rap on, “I’ll tell you what we’ll do, you and

I. I’m Dan’s uncle, but I’m more than that. Since he lost his father and

mother I’ve been his foster father. And I’ll say this: he’s always done

what I commanded him to do.

“You’ll wonder perhaps why he didn’t tell you all I’ve

just told you? Well, the reason is likely this: Dan’s got a lot of

pride, and the chances are, when he approached you, and asked you for

your daughter, you put the gaff in him and froze him up. Nevertheless,

the young cub should have enlightened you, and I told him so. But I’m

doing it now, and I hope it isn’t too late to put a different aspect on

things.

“Now, here’s what I’ve got to propose. He’s got money of

his own, a good education, and he’s an A1 judge of timber. He wants to

start in business in this section, so I’m going to build him a big

sawmill near the mouth of Indian Creek. And I want to say right here,

McDonald, with you and Flora and myself believing in him—he’s going to

make good.”

He sat back, his booted legs spread wide, a smile of huge

satisfaction on his big face.

I went into the bedroom and brought out the bottle which

my father had carried with him from Scotland. Heaven only knows how old

the amber liquor it contained was, but, judging from the way that

connoisseur Hallibut and Red McDonald smacked their lips after drinking

to the health of the newly wedded pair, and again to their prosperity,

and once more to their own better acquaintance, and again to myself—I

know it was sufficiently potent to bring those two men into closer

understanding of each other; and that was a great deal.

In the weeks that followed I was busy with the

woodcutting and the building of new racks and outbuildings. My stock of

cattle was growing. Twelve new lambs were among my sheep and others were

expected. In March I bought another horse. I did not sell my oxen.

Somehow, I couldn’t bear to see them go. Father had broken that span of

steers, and—of course, I know it was only a fancy—but somehow, when they

raised their heavy heads in the morning when I went out to feed them,

their soft eyes seemed to watch for him, their ears twitch for the sound

of his footstep.

Jack Cameron and Nance were now living in a house close

to the Cameron home. Dan Whitelaw and Flora were living with her parents

until his own house of lumber could be built near the site of this mill

in the spring. Colonel Hallibut often rode over to visit McDonald now;

the two had become great friends. |