|

The Land and the People

FROM the most southern

point of Onttario on Lake Erie, near the 42nd parallel of latitude, to

Moose Factory on James Bay, the distance is about 750 miles. From the

eastern boundary on the Ottawa and St Laurence Rivers to Kenora at the

Manitoba boundary, the distance is about 1000 miles. The area lying

within these extremes is about 220,000 square miles. In Iyi2 a northern

addition of over 100,000 square miles was made to the surface area of

the province, but it is doubtful whether the agricultural lands will

thereby be increased. Of this large area about 25,000,000 acres are

occupied and assessed, including farm lands and town and city sites. It

will be seen, therefore, that only a small fraction of the province has,

as yet, been occupied. Practically all the occupied area is south of a

line drawn through Montreal, Ottawa, and Sault Ste Marie, and forms part

of the great productive zone of the continent.

The next point to be

noted is the irregularity of the boundary the greater portion of

which is water—Lakes Superior, Huron, Erie, Ontario, the St Lawrence

River, the Ottawa River, James Bay, and Hudson Bay. The modifying effect

of great bodies of water must be considered in studying the agricultural

possibilities of Ontario.

Across this great area

of irregular outline there passes a branch of the Archaean rocks running

in a north-western direction and forming a watershed, which turns some

of the streams to Hudson Bay and the others to the St Lawrence system.

An undulating surface has resulted, more or less filled with lakes, and

almost lavishly supplied with streams, which are of prime importance for

agricultural life and of incalculable value for commercial purpose. To

these old rocks which form the backbone of the province may be traced

the origin of the large stretches of rich soil with which the province

abounds.

An examination of the

map, and even a limited knowledge of the geological history of the

province, will lead to the conclusion that in Ontario there must be a

wide range in the nature and composition of the soils and a great

variety in the climatic conditions. These conditions exist, and they

result a varied natural production. In the extreme southwestern

section plants of a semi-tropical nature were to be found in the early

days in luxurious growth; while in the extreme north, spruce, somewhat

stunted in size and toughened in fibre, are still to be found in vast

forests.

It is with the southern

section, that lying south of the Laurentian rocks, that our story is

mainly concerned, for the occupation and exploitation of the northland

is a matter only of recent date. Nature provided conditions for a

diversified agriculture. It is to such a land that for over a hundred

years people of different nationalities, with their varied trainings and

inclinations, have been coming to make their homes. We may expect,

therefore, to find a great diversity in the agricultural growth of

various sections, due partly to the variety of natural conditions and

partly to the varied agricultural training of the settlers in their

homelands.

Early Settlement,

1783-1816

Originally this

province was covered with forest, varied and extensive, and was valued

only for its game. The hunter and trapper was the pioneer. To protect

and assist him, fortified posts were constructed at commanding points

along the great waterways. In the immediate vicinity of these posts

agriculture, crude in its nature' and restricted in its area, had its

beginning.

It was into this wooded

wilderness that the United Empire Loyalists, numbering in all

approximately ten thousand people, came in the latter part of the

eighteenth century.

They were a people of

varied origins—Highland Scottish, German, Dutch, Irish Palatine, French

Huguenot, English. A lot of them had lived on farms in New York State,

and therefore brought with them some knowledge and experience that stood

them in good stead in their arduous work of making new homes in a land

that was heavily wooded. In the year 1783 prospectors were sent into

Western Quebec, the region lying west of the Ottawa River, and

selections were made for them in four districts—along the St Lawrence,

opposite Fort Oswegatchie; around the Bay of Quinte, above Fort

Cataraqui; in the Niagara peninsula, opposite Fort Niagara ; and in the

south-western section, within reach of Fort Detroit. Two reasons

determined these locations; first, the necessity of being located on

the water-front, as lake and river were the only highways available;

and, secondly, the advisability of being within the protection of a

fortified post. The dependence of the settlers upon the military would be

realized when we remember that they had neither implements nor seed

grain. In fact, they were dependent at first upon the government stores

for their food. It is difficult at the present time to realize the

hardships and appreciate the conditions under which these United Empire

Loyalist settlers began life in the forest of 1784.

Having been assigned

their lots and supplied with a few implements, they began their work of

making small clearings and the erection of rude log-houses and barns.

Among the stumps they sowed the small quantities of wheat, oats, and

potatoes that were furnished from the government stores. Cattle were for

many years few in number, and the settler, to supply his family with

food and clothing, was compelled to add hunting and trapping to his

occupation of felling the trees.

Gradually the clearings

became larger and the area sown increased in size. The trails were

improved and took on the semblance of roads, but the waterways continued

to be the principal avenues of communication. In each of the four

districts the government created mills to grind the grain for the

settlers. These were known as the King’s Mills. Waterpower mills were

located near Kingston, at Gananoque, at Napanee, and on the Niagara

River. The mill on the Detroit was run by wind power. An important event

in the early years was when the head of the family set out for the mill

with his bag of wheat on his back or in his canoe, and returned in two

or three days, perhaps in a week, with a small supply of flour. In the

early days there was no wheat for export. The question then may be

asked, was there anything to market? Yes; as the development went on,

the settlers found a market for two surplus products, timber and potash.

The larger pine trees were hewn into timber and floated down the streams

to some convenient point where they were collected into rafts, which

were taken down the St Lawrence to Montreal and Quebec. Black salt or

crude potash was obtained by concentrating the ashes that resulted from

burning the brush and trees that were not suitable for timber.

For the first thirty

years of the new settlements the chief concern of the people was the

clearing of their land, the increasing of their field crops, and the

improving of their homes and furnishings. It was slow going, and had it

not been for government assistance, progress, and even maintenance of

life, would have been impossible. That was the heroic age of Upper

Canada, the period of foundation-laying in the province. Farming was the

main occupation, and men, women, and children shared the burdens in the

forest, in the field, and in the home. Roads were few and poorly built,

except the three great military roads planned by Lieutenant-Governor

Simcoe running east, west, and north from the town of York. Social

intercourse was of a limited nature. Here and there a school was formed

when a competent teacher could be secured. Church services were held

once a month, on which occasions the missionary preacher rode into the

district on horseback. Perhaps once or twice in the summer the weary

postman, with his pack on his buck, arrived at the isolated farmhouse to

leave a letter, on which heavy toll had to be collected.

Progress was slow in

those days, but after thirty years fair hope of an agricultural country

was beginning to dawn upon the people when the War of 1812 broke out. By

this time the population of the province had increased to about eighty

thousand. During this first thirty years very little had been done in

the way of stimulating public interest in agricultural work. Conditions

were not favourable to organization. The ‘town meeting’ was concerned

mainly with the question of the height of fences and regulations as to

stock running at large. One attempt, however, was made which should be

noted. Lieutenant-Governor Simcoe took charge of affairs early in 1792,

and, immediately after the close of the first session of the legislature

at Newark (Niagara) in the autumn of that year, organized an

agricultural society at the headquarters which met occasionally to

discuss agricultural questions. There are no records to show whether

social intercourse or practical agricultural matters formed the main

business. The struggle for existence was too exacting and the conditions

were not yet favourable for organization to advance general agricultural

matters.

When the War of 1812

broke out the clearings of the original settlers had been extended, and

some of the loyalists still lived, grown grey with time and hardened by

the rough life of the backwoods. Their sons, many of whom had faint

recollection of their early home's across the line, had grown up in an

atmosphere of strictest loyalty to the British crown, and had put in

long years in clearing the farms on which they lived and adding such

comforts to their houses, that to them, perhaps as to no other

generation, their homes meant everything in life. The summons came to

help to defend those homes and their province. For three years the

agricultural growth received a severe check. Fathers and sons took their

turn in going to the front. The cultivation of the fields, the sowing

and the harvesting of the crops, fell largely to the lot of the mothers and the daughters left at home. But they were equal to it. In those days

the women were trained to help in the work of the fields. They did men’s

work willingly and well. In many cases they had to continue their

heroic, work after the close of the war, until their surviving boys were

grow in to years of manhood, for many husbands and sons went to the front

never to return.

A Period of Expansion,

1816-46

The close of the war

saw a province that had been checked at a time of vigorous growth now

more or less impoverished, and, in some sections, devastated. This was,

however, but the gloomy outlook before a period of rapid expansion. In

1816, on the close of the Napoleonic wars in Europe, large numbers of

troops were disbanded, and for these new homes and new occupations had

to be found. Then began the first emigration from Britain overseas to

Upper Canada. All over the British Isles little groups were forming of

old soldiers reunited to their families. A few household furnishings

were packed, a supply of provisions laid in, a sailing vessel chartered,

and the trek began across the Atlantic. The emigrants sailed from many

ports of England, Scotland, and Ireland. Sometimes the trip was made in

three or four weeks; but often, through contrary winds or rough

weather, three or four months passed before the vessel sailed up the St

Lawrence and landed the newcomers at Montreal. Hardly half of their

difficulties were then overcome or half of their dangers passed. If they

were to find their new locations by land, they must walk or travel by

slow ox-cart; if they journeyed by water, they must make their way up

the St Lawrence by open boat, surmounting the many rapids in succession,

poling the boats, pulling against the stream, at times helping to carry

heavy loads over the portages. Their new homes in the backwoods were in

townships in the rear of those settled by the loyalists, or in

unoccupied areas lying on the lake-fronts between the four districts

referred to as having been taken up by the loyalists. Then began the

settlements along the north shore of Lake Ontario and of Lake Erie, and

the population moved forward steadily. In 1816 the total population of

the province was approximately 100,000; by 1826, according to returns

made to the government, it had increased to 166,000; in 1836 it was

374,000, and in 1841 it was 456,000. The great majority of these people,

of course, lived upon the land, the towns being comparatively small, and

the villages were composed largely of people engaged in agricultural

work.

This peaceful British

invasion contributed a new element to the province and added still

further to the variety of the people. In one township could be found a

group of English settlers, most of whom came from a southern county of

England, near by a township peopled by Scottish Lowlanders, and not far

away a colony of north of Ireland farmers, or perhaps a settlement

composed entirely of people from the vicinity of Cork or Limerick.

These British settlers

brought new lines of life, new plans for houses and barns, new methods

of cultivation, new varieties of seed, and, what was perhaps of most

influence upon the agricultural life of the province, new kinds of live

stock. Even to this day can be seen traces of the differences in

construction of buildings introduced by the different nationalities that

came as pioneers into the various sections of the province—the French

Canadian constructed his buildings with long, steep roofs; the

Englishman followed his home plan of many small, low outbuildings with

doors somewhat rounded at the top; the German and Dutch settler built

big barns with their capacious mows. These latter have become the type

now generally followed, the main improvement in later years being the

raising of the frames upon stone foundations so as to provide

accommodation for live stock in the basement. It would be interesting

and profitable to study carefully the different localities to determine

what elements have contributed to the peculiar agricultural

characteristics of the present day. In this connection the language also

might be investigated. For instance, to the early Dutch farmers of Upper

Canada we owe such common words as ‘stoop,' ‘bush,’ ‘boss,’ 'span.’

To the early British settler these were foreign words. When the oversea

settlers came up the St Lawrence they were transported from Montreal

either by ‘bateau ’ or by ‘Durham boat.’

Special reference must

be made to the live stock introduced by the British settlers. This was one

of the most important elements in the expansion and permanent

development of the agriculture of the province. The British Isles have

long been noted for their pure-bred stock. In no other part of the world

have so many varieties been originated and improved. In horses, there

are the Clydesdale, the Shire, the Thoroughbred, and the Hackney; in

cattle, Shorthorns, Herefords, Ayrshires, Devon, and the dairy breeds

of Jersey and Guernsey; in sheep, Southdowns, Shropshires, Leicesters;

in swine, Berkshires and Yorkshires. Many other breeds might be added to

these. Poultry and dogs also might be referred to. The Britisher has

been noted for his love of live stock. He has been trained to their

care, his agricultural methods have been ordered to provide food

suitable for their wants, and he has been careful to observe the lines

of breeding so as to improve their quality. In the earliest period of

the settlement of the province live stock was not numerous and the

quality was not of the best. Whatever was to be found on the farms came

mainly from the United States and was of inferior type. The means of

bringing in horses, cattle, and sheep were limited. The result was that

field work at that time was largely done by hand labour. Hunting and

fishing helped to supply the table with the food that to-day we obtain

from the butcher. When the Britisher came across the Atlantic he brought

to Upper Canada his love for live stock and his knowledge how to breed

and care for the same. The result was seen in the rapid increase in the

number of horses, cattle, sheep, and swine, and the placing of the

agriculture of the province on a firm basis for future growth.

By 1830 the population

had grown to about 213.000, practically all located on the land. In that

year there were only five towns of 1000 or over: namely, Kingston, 3587;

York (Toronto), 2860; London, (including the township), 2415; Hamilton

(including the township), 2013; and Brockville, 1130. The returns to the

government show that of the 4.,018,385 acres occupied 773,727 were under

cultivation. On the farms were to be found 30,776 horses, 33,517 oxen,

80,892 milch cows, and 32,537 young cattle. It is interesting to note

that oxen, so useful in clearing land and in doing heavy work, were more

numerous than horses. Oxen were hardier than horses; they could forage

for themselves and live on rough food, and when disabled could be

converted into food. They thus played a very important part in the

pioneer 1ife. There were no improved farm implements in those days: the

plough, the spade, the hoe, the fork, the sickle, the hook, the cradle,

and the rake— implements that had been the husbandman’s equipment for

centuries—completed the list. With these the farmer cultivated his lands

and gathered his crops. With two stout hickory poles, joined together at

the end with tough leather thongs, a flail was made with which he

threshed out his grain on the floor of his barn.

The earliest pioneers

raised some flax, and from the fibre made coarse linen fabrics,

supplementing these by skins of wild animals and the backs of cattle.

With the introduction of sheep by the British settlers wool became an

important product, and homespun garments provided additional clothing

for all the members of the family. Seeds of various fruit trees were

planted, and by 1830 the products of these seedlings supplemented the

wild plums and cherries of the woods and the wild raspberries that

sprang up in abundance in the clearings and slashes. By this time every

farm had one or more milch cows and the farmer’s table: was supplied

with fresh milk, butter, and home-made cheese. As the first half century

of the province was drawing to its close, some of the comforts of home

life began to be realized by the farming community. The isolation of the

former period disappeared as roads of communication were opened up and

extended.

Here and there

societies were formed for the exhibition of the products of the farm and

for friendly competitions. So important were these societies becoming in

the life of the whole community that in 1830 the government gave them

recognition and provided an annual grant to assist them in their work.

This is an important event in agricultural history, for it marks the

beginning of government assistance to the agricultural industry. Between

1820 and 1830 probably not more than half a dozen agricultural societies

were organized. Some records of such were preserved at York, Kingston,

and in the Newcastle district. From the record of the County of

Northumberland Agricultural Society it is learned that its first show

was held in the public square of the village of Colborne on October 19,

1828, when premiums were awarded amounting in all to seventy-seven

dollars. There were fourteen prizes for live stock, two prizes for

cheese, two for field rollers, and two for essays on the culture of

wheat. The first prize essay, for which the winner received five

dollars, was printed for distribution. The prize list was limited in

range, but it shows how this new settlement, formed largely by British

settlers since 1816, was giving particular attention to the

encouragement of live stock. A short quotation from the prize essay as

to the best method of clearing the land for wheat should be found of

interest.

As a great part of our

County is yet in a wilderness state and quite a share of the wheat

brought to our markets is reared on new land, I deem it important that

our enterprising young men who are clearing away the forest should know

how to profit by their hard labor. Let the underwood be cut in the

autumn before the leaves fall, and the large timber in the winter or

early in the spring. This will .sure a good burn, which is the first

thing requisite for a good crop. Do your logging in the month of June,

and if you wish to make money, do it before you bum your brush and save

the ashes; these will more than half pay you for clearing the land: and

by burning at this season you will attract a drove of cattle about you

that will destroy all sprouts which may be growing; do not leave more

than four trees on an acre and girdle these in the full moon of March

and they will never leaf again; thus you may have your land prepared for

the seed before harvest.

The act of 1830

provided a grant of £100 for a society in each district, upon condition

that the members subscribed and paid in at least £50, and in the case of

a society being organized in each county the amount was to be equally

divided among the societies. The condition of making the grant was set

forth in the act as follows: 'When any Agricultural Society, for the

purpose of importing valuable live stork, grain, grass seeds, useful

implements or whatever else might conduce to the improvement of

agriculture in this Province,’ etc.

As a result of this

substantial assistance by the government, agricultural societies

increased in number, and their influence, in assisting in the

improvement of the live stock and the bringing of new implements to the

attention of farmers, was most marked.

Horses, sheep, and

milch cows increased rapidly. Purebred cattle now began to receive some

attention. The first record of importation is the bringing of a

Shorthorn bull and a cow from New York State in 1831 by Robert Arnold of

St Catharines. In 1833 Rowland Wingfield, an Englishman farming near

Guelph, brought a small herd of choice animals across the ocean, landed

them at Montreal, took them to Hamilton by way of the Ottawa River, the

Rideau Canal, and Lake Ontario, and then drove them on foot to

Wellington County. The Hon. Adam Fergusson of Woodhill followed two or

three years later with a similar importation.

The first Ayrshire

cattle can be traced back to the Scottish settlers who arrived during

this period. These emigrants had provided their own food for the voyage

to Canada, and in some cases brought a good milch cow to provide fresh

milk on the voyage. She would be disposed of on landing, at Montreal or

in the eastern part of Upper Canada. This accounts for the early

predominance of Ayrshires in Eastern Ontario. Thus to the period 1830-45

belongs the first foundation of the pure-bred stock industry.

It was in this period

also that the first signs appear of improved farm implements and labour-saving

machinery. Ploughs of improved pattern, lighter and more effective, were

being made. Land rollers and harrows made in the factory began to take

the place of the home-made articles. Crude threshing machines,

clover-seed cleaners, root-cutters, and a simple but heavy form of

hay-rake came into use. The mowing machine and the reaper were making

their appearance in Great Britain and the United States, but they had

not yet reached Upper Canada.

The organization of

agricultural societies in the various districts, and the great impetus

given to the keeping of good stock, led in 1843 to the suggestion that a

provincial organization would be of benefit to the farming industry. In

the neighbouring State of New York a similar organization had been in

existence since 1832 and successful State fairs had been held, which

some of the more prominent farmers of Upper Canada had visited. An

agricultural paper called the British American Cultivator had been

established in York, and through this paper, in letters and editorials,

the idea of a provincial association was advocated. For three years the

discussion proceeded, until finally, in 1846, there was organized the

Provincial Agricultural Association and Board of Agriculture for Canada

West, composed of delegates from the various district societies. The

result was that the first provincial exhibition was held in Toronto on

October 21 and 22 of that year. The old Government House at the

south-western corner of King Street and Simcoe Street, then empty, was

used for the exhibits, and the stock and implements were displayed in

the adjoining grounds. The Canada Company gave a contribution of $200,

eight local societies made donations, about $280 was secured as gate

money, and 297 members paid subscriptions. Premiums were paid to the

amount of $880, the bulk of which went to live stock; books, which cost

about $270, were given as prizes; and there was left a cash balance on

hand of $400. A ploughing match was held, and on the evening of the

first day a grand banquet was given, attended by the officers and

directors and by some of the leading citizens of Toronto. Among the

speakers at the banquet were Chief Justice Robinson and Egerton Ryerson,

superintendent of education.

Organized Agriculture,

1846-67

The organization of

this provincial association fittingly introduces another era in

agricultural growth. It is to be noted that this provincial organization

was a self-created body; it drew at first no government funds direct. It

commended itself to the people, for on July 28, 1847, the provincial

parliament in session at Montreal passed an act incorporating it under

the name of the Agricultural Association of Upper Canada, and in the

charter named as members a number of the leading citizens of the

province.

It was governed by a

board of directors, two of whom were chosen annually by each district

agricultural society. The objects set forth were the improvement of farm

stock and produce, the improvement of agricultural implements, and the

encouragement of domestic manufactures, of useful inventions applicable

to agricultural or domestic purposes, and of every branch of rural and

domestic economy. Out of this provincial association came all the

further agricultural organizations of a provincial nature, and

ultimately, some forty years later, the Ontario department of

Agriculture.

The second provincial

exhibition was held at Hamilton in 1847, and Lord Elgin, the

governor-general, was in attendance. He was also a generous patron, for

his name appears as a donor of $100. The address which he delivered at

the banquet has been preserved in the published records and is copiously

marked with cheers and loud applause.

The third exhibition

was held at Cobourg in 1848. The official report of the exhibits

indicates that pure-bred stock was rapidly increasing and improving in

quality; but the most significant paragraph is that dealing with

implements, and this is well worth quoting in full.

Of implements of Canada

make, the Show was deficient; and we were much indebted to our American

neighbours for their valuable aid on this occasion. A large number of

ploughs, straw-cutters, drills, corn-shellers, chums, etc., etc., were

brought over by Messrs Briggs & Co. of Rochester, Mr Emery of Albany,

and a large manufacturing firm near Boston. Mr Bell of Toronto exhibited

his excellent plough, straw-cutter, and reaping machine, the first

prize for the latter article was awarded to Mr Helm of Cobourg for the

recent improvements which he has effected. Mr Clark of Paris exhibited

his one-horse thrashing-mill, which attracted much attention.

At the fourth

exhibition, held at Kingston in 1849, the show of implements was much

more extensive, and comment was made on the improvement of articles of

home manufacture. At this meeting Professor J. F. W. Johnson, of

Edinburgh, who was making a tour of North America, was present.

The address of the

president, Henry Ruttan of Cobourg, is a most valuable reference article

descriptive of the agricultural progress of the province from the first

settlements in 1783 to the time of the exhibition. Ruttan was a

loyalist’s son, and, from his own personal knowledge, he described the

old plough that was given by the government to each of the first

settlers.

It consisted of a small

iron socket, whose point entered by means of a dove-tailed aperture into

the heel of the coulter, which formed the principal part of the plough,

and was in shape similar to the letter L, the shank of which went

through the wooden beam, and the foot formed the point which was

sharpened for operation. One handle and a plank split from the side of a

winding block of timber, which did duty for the mould-board, completed

the implement. Besides provisions for a year, I think each family had

issued to them a plough-share and coulter, a set of dragg-teeth, a log

chain, an axe, a saw, a hammer, a bill hook and a grubbing hoe, a pair

of hand-irons and a cross-cut saw amongst several families, and a few

other articles.

He then refers to the

large number of implements then being pressed upon the farmers, until

‘they have almost become a nuisance to the farmer who desires to

purchase a really useful article.’ All of which indicates that a

distinctive feature of the period beginning with 1846 was the

introduction and rapid extension of improved farm machinery.

A few words as to the

reaping machine, which contributed more than any other modern implement

to the development of agriculture in the past century, may not be out of

place. Various attempts had been made at producing a machine to

supersede the sickle, the scythe, and the cradle before the Rev. Patrick

Bell, in 1826, presented his machine to the Highland Agricultural

Society of Scotland for its examination. Bell’s machine was fairly

successful, and one was then in operation on the farm of his brother,

Inch-Michael, in the Carse of Gowrie. One set of knives was fixed,

another set worked above and across these like the blades of a pair of

scissors. The grain fell on an endless cloth which carried and deposited

the heads at the side of the machine. A horse pushed it forward and kept

all parts in motion. It was simple, and, we are told, harvested twelve

acres in a day. This was in 1826. In the New York Farmer and American

Gardener's Magazine for 1834 may be found the descriptions and

illustrations of Obed Hussey’s grain-cutter and Cyrus H. McCormick’s ‘improved reaping-machine.’ The question has been raised as to whether

either of these United States inventions owed anything to the earlier

production of Patrick Bell. It was, of course, the improved United

States reaping machines that found their way into Upper Canada shortly

after the organization of the Provincial Agricultural Association. Our

interest in this matter is quickened by the fact that the Rev. Patrick

Bell, when a young man, was for some time a tutor in the family of a

well-to-do farmer in the county of Wellington, and there is a tradition

that while there he carried on some experiments in the origination of

his machine. The suggestion of a ‘mysterious visitor’ from the United

States to the place where he was experimenting is probably mere conjecture.

This period, 1846 to

1867, was one of rapid growth in population. The free-grant land policy

of the government was a great attraction for tens of thousands of people

in the British Isles, who were impelled by social unrest, failure of

crops, and general stagnation in the manufacturing industries to seek

new homes across the sea. In the twenty years referred to the popular in

more than doubled, and the improved lands of the province increased

fourfold. The numbers of cattle and sheep about doubled, and the wheat

production increased about threefold.

Towards the latter part

of the period a new agricultural industry came into existence—the

manufacture of cheese in factories. It was in New York State that the

idea of cooperation in the manufacture of cheese was first attempted.

There, as in Canada West, it had been the practice to make at home from

time to time a quantity of soft cheese, which, of course, would be of

variable quality. To save labour, a proposition was made to collect the

milk from several farms and have the cheese made at one central farm.

The success of this method soon became known and small factories were

established. In 1863 Harvey Farrington came from New York State to

Canada West and established a factory in the county of Oxford, about the

same time that a similar factory was established in the county of

Missisquoi, Quebec. Shortly afterwards factories were built in Hastings

County, and near Brockville, in Leeds County. Thus began an industry

that had a slow advance for some fifteen years, but from 1880 spread

rapidly, until the manufacture of cheese in factories became one of the

leading provincial industries. The system followed is a slight

modification of the Cheddar system, which takes its name from one of the

most beautiful places in the west of England. Its rapid progress has

been due to the following circumstances: Ontario, with her rich grasses,

clear skies, and clean springs and streams, is well adapted to dairying;

large numbers of her farmers came from dairy districts in the mother

country; the co-operative method of manufacture tends to produce a

marketable article that can be shipped and that improves with proper

storage; Great Britain has proved a fine market for such an article; and

the industry has for over thirty years received the special help and

careful supervision and direction of the provincial and Dominion

governments.

During this period we

note the voluntary organization of the Ontario Fruit-Growers’

Association, a fact which alone would suggest that the production of

fruit must have been making progress. The early French settlers along

the Detroit River had planted pear trees or grown them from seed, and a

few of these sturdy, stalwart trees, over a century old, still stand and

bear some fruit. Mrs Simcoe, in her Journal, July 2, 1793, states: ‘We

have thirty large May Duke cherry trees behind the house and three

standard peach trees which supplied us last Autumn for tarts and

desserts during six weeks, besides the numbers the young men eat.’ This

was at Niagara. The records of the agricultural exhibitions indicate

that there was a gradual extension of fruit growing. Importations of new

varieties were made, Rochester, in New York State, apparently being the

chief place from which nursery stock was obtained. Here and there

through the province gentlemen having some leisure and the skill to

experiment were beginning to take an interest in their gardens and to

produce new varieties. On January 19, 1859, a few persons met in the

board-room of the Mechanics’ Hall at Hamilton and organized a

fruit-growers’ association for Upper Canada. Judge Campbell was elected

president; Dr Hurlbert, first vice-president; George Leslie, second

vice-president; Arthur Harvey, secretary. The members of this

association introduced new varieties and reported on their success. They

were particularly active in producing such new varieties as were

peculiarly suitable to the climate. For nine years they maintained their

organization and carried on their work unaided and unrecognized

officially.

To this period belongs

also the first attempts at special instruction in agriculture and the

beginning of an agricultural press. Both are intimately connected with

the association, already referred to, that had been organized in 1846 by

some of the most progressive citizens.

For four years the

Provincial Association carried on its work and established itself as a

part of the agricultural life of Canada West. In 1850 the government

stepped in and established a board of agriculture as the executive of

the association. Its objects were set out by statute and funds were to

be provided for its maintenance. The new lines of work allotted to it

were to collect agricultural statistics, prepare crop reports, gather

information of general value and to present the same to the legislature

for publication, and to co-operate with the provincial university in the

teaching of agriculture and the carrying on of an experimental or

illustrative farm. Professor George Buckland was appointed to the chair

of agriculture in the university in January 1851 and an experimental

farm on a small scale was laid out on the university grounds. Professor

Buckland acted also as secretary to the board until 1858, when he

resigned and was succeeded by Hugh C. Thomson. He continued his work for

some years at the university, and was an active participant in all

agricultural matters up to the time of his death in 1885.

Provision having been

made for agricultural instruction at the university, the board in 1859

decided to establish a course in veterinary science, and at once got

into communication with Professor Dick of the Veterinary College at

Edinburgh, Scotland. In 1862 a school was opened in Toronto under the

direction of Professor Andrew Smith, recently arrived from Edinburgh.

The British American

Cultivator was established in 1841 by Eastwood and Co. and W. G.

Edmundson, with the latter as editor. It gave place in 1849 to the

Canadian Agriculturist, a monthly journal edited and owned by George

Buckland and William McDougall. This was the official organ of the board

till the year 1864., when George Brown began the publication of the

Canada Farmer with the Rev. W. F. Clark as editor-in-chief and D. W.

Beadle as horticultural editor. The board at once recognized it,

accepted it as their representative, and the Canadian Agriculturist

ceased publication in December 1863.

The half-century of

British immigration, 1816 to 1867, had wrought a wonderful change. From

a little over a hundred thousand the population had grown to a million

and a half; towns and cities had sprung into existence; commercial

enterprises had taken shape; the construction of railways had been

undertaken; trade had developed along new lines; the standards of living

had materially changed; and great questions, national and international,

had stirred the people and aroused at times the bitterest political

strife. The changed standards of living can best be illustrated by an

extract from an address delivered in 1849 by Sheriff Ruttan. Referring

to the earlier period, he said :

Our food was coarse but

wholesome. With the exception of three or four pounds of green tea a

year for a family, which cost us three bushels of wheat per pound, we

raised everything we ate. We manufactured our own clothes and purchased

nothing except now and then a black silk handkerchief or some trifling

article of foreign manufacture of the kind. We lived simply, yet

comfortably—envied no one, for no one was better off than his neighbour.

Until within the last thirty years, one hundred bushels of wheat, at 2s.

6d. per bushel, was quite sufficient to give in exchange for all the

articles of foreign manufacture consumed by a large family. . . . The

old-fashioned home-made cloth has given way to the fine broadcloth coat;

the linsey-woolsey dresses of females have disappeared and English and

French silks been substituted; the nice clean-scoured floors of the

farmers’ houses have been covered by Brussels carpets; the spinning

wheel and loom have been superseded by the piano; and in short, a

complete revolution in all our domestic habits and manners has taken

place—the consequences of which are the accumulation of an enormous debt

upon our shoulders and its natural concomitant, political strife.

Students of Canadian

history will at once recall the story of the Rebellion of 1837. the

struggle for constitutional government, the investigation by Lord

Durham, the repeal of the preferential wheat duties in England, the

agitation for Canadian independence, and other great questions that so

seriously disturbed the peace of the Canadian people. They were the

‘growing pains’ of a progressive people. The Crimean War, in 1854-56,

gave an important though temporary boom to Canadian farm products.

Reciprocity with the United States from 1855 to 1866 offered a

profitable market that had been closed for many years. Then came the

close of the great civil war in the United States and the opening up of

the cheap, fertile prairie lands of the Middle West to the hundreds of

thousands of farmers set free from military service. This westward

movement was joined by many farmers from Ontario; there was a

disastrous competition in products, and an era of agricultural

depression set in just before Confederation. It was because of these

difficulties that Confederation became a possibility and a necessity.

The new political era introduced a new agricultural period, which began

under conditions that were perhaps as unfavourable and as unpromising as

had been experienced for over half a century.

The Growth of Scientific

Farming, 1867-88

The period that we

shall now deal with begins with Confederation in 1867 and extends to

1888, when a provincial minister of Agriculture was appointed for the

first time and an independent department organized.

From 1792 to 1841 what

is now Ontario was known as Upper Canada; from 1841 to 1867 it was part

of the United Province of Canada, being known as Canada West to

distinguish it from Quebec or Canada East. In 1867, however, it resumed

its former status as a separate province, but with the new name of

Ontario. In the formation of the government of the province agriculture

was placed under the care of a commissioner, who, however, held another

portfolio in the cabinet. John Carling was appointed commissioner of

Public Works and also commissioner of Agriculture. On taking office

Carling found the following agricultural organizations of the province

ready to co-operate with the government: sixty-three district

agricultural societies, each having one or more branch township

societies under its care, and all receiving annual government grants of

slightly over $50,000; a provincial board of agriculture, with its

educational and exhibition work; and a fruit-growers’ association, now

for the first time taken under government direction ami given financial

assistance.

One extract from the

commissioner’s first report wlll serve to show the condition of

agriculture in Ontario when the Dominion was born. ‘It is an encouraging

fact that during the last year in particular mowers and reapers and labour-saving improvements have not only increased in the older

districts, but have found their way into new ones, and into places where

they were before practically unknown. This beneficial result has, no

doubt, mainly arisen from the difficulty, or rather in some cases

impossibility, of getting labour at any price.’ It would appear,

therefore, that the question of shortage of farm labour, so much

complained of in recent years, has been a live one for forty years and

more.

In the second report of

the commissioner (1869) special attention was directed to the question

of agricultural education, and the suggestion was made that the

agricultural department of the university and the veterinary college

might give some instruction to the teachers at the normal school. In the

following year, however, an advanced step was taken.

It was noted that Dr

Ryerson was in sympathy with special agricultural teaching and had

himself prepared and published a text-book on agriculture. The

suggestion was made that the time had arrived for a school of practical

science. At the same time Ryerson had appointed the Rev. W. F. Clark,

the editor of the Canada Farmer, to visit the Agricultural department at

Washington and a few of the agricultural colleges of the United States,

and to collect such practical information as would aid in commencing

something of an analogous character in Ontario. It will thus be seen

that the two branches of technical training—the School of Practical

Science and the Agricultural College—were really twin institutions,

originating, in the year 1870, in the dual department of Public Works

and Agriculture. These institutions were the outcome of the correlation

of city and country industries, which were under the fostering care of

the Agriculture and Arts Association, as the old provincial organization

was now known. The School of Practical Science, it may be noted, is now

incorporated with the provincial university, and the Agricultural

College is affiliated with it.

There were at that time

two outstanding agricultural colleges in the United States, that of

Massachusetts and that of Michigan. These were visited, and, based upon

the work done at these institutions, a comprehensive and suggestive

report was compiled. Immediate action was taken upon the recommendations

of this report, and a tract of land, six hundred acres in extent, was

purchased at Mimiro, seven miles west of Toronto. Before work could be

commenced, however, the life of the legislature closed and a new

government came into office in 1871 with Archibald McKellar as

commissioner of Agriculture and Arts. New governments feel called upon

to promote new measures. There were rumours and suggestions that the

soil of the Mimico farm was productive of thistles and better adapted to

brick-making than to the raising of crops. Also the location was so

close to Toronto that it was feared that the attractions of the city

would tend to make the students discontented with country life. For

various reasons a change of location was deemed desirable, and a

committee of farmer members of the legislature was appointed. Professor

Miles, of the Michigan Agricultural College, was engaged to give expert

advice; other locations were examined, and finally Moreton Lodge Farm,

near Guelph, was purchased. After some preliminary difficulties,

involving the assistance of a sheriff or bailiff, possession was

obtained, and the first class for instruction in agricultural science

and practice, consisting of thirty-one pupils in all, was opened on June

I, 1874, with William Johnston as rector or principal. Thus was

established the Ontario School of Agriculture, now known as the Ontario

Agricultural College. Its annual enrolment has grown to over fifteen

hundred, and it is now recognized as the best-equipped and most

successful institution of its kind in the British Empire. Its

development along practical lines and its recognition as a potent factor

in provincial growth were largely due to Dr James Mills, who was

appointed president of the college in 1879, and filled that position

until January 1904, when he was appointed to the Dominion Board of

Railway Commissioners. Under his direction farmers’ institutes were

established in Ontario in 1884. Dr Mills was succeeded by Dr G. C. Creelman as president.

The next important step

in agricultural advancement was the appointment in 1880 of the Ontario

Agricultural Commission ‘to inquire into the agricultural resources of

the Province of Ontario, the progress and condition of agriculture

therein and matters connected therewith.’ The commission consisted of S.

C. Wood, then commissioner of Agriculture (chairman), Alfred II. Dymond

(secretary), and sixteen other persons representative of the various

agricultural interests, including the president and ex-president of the

Agricultural and Arts Association, Professor William Brown of the

Agricultural College, the master of the Dominion Grange, the president

of the Entomological Society, and two members of the legislature, Thomas

Ballantyne and John Dryden. In 1913 there were but two survivors of this

important commission, J. B. Aylesworth of Newburg, Ont., and Dr William

Saunders, who, after over twenty years’ service as director of the

Dominion Experimental Farms, had resigned office in 1911.

All parts of the

province were visited and information was gathered from the leading

farmers along the lines laid down in the royal commission. In 1881 the

report was issued in five volumes. It was without doubt the most

valuable commission report ever issued in Ontario, if not in all Canada.

Part of it was reissued a second and a third time, and for years it

formed the Ontario farmer’s library. Even to this day it is a valuable

work of reference, containing as it does a vast amount of practical

information and forming an invaluable source of agricultural history.

Volume 1 |

Volume 2 |

Volume 3 |

Volume 4 |

Volume 5

The first outcome of

this report was the establishment, in 1882, by the government of the

Ontario bureau of Industries, an organization for the collection and

publication of statistics in connection with agriculture and allied

industries. Archibald Blue, who now occupies the position of chief

officer of the census and statistics branch of the Dominion service, was

appointed the first secretary of the bureau.

Agriculture continued

to expand, and associations for the protection and encouragement of

special lines increased in number and in importance. Thus there were no

fewer than three vigorous associations interested in dairying: the

Dairymen’s Association of Eastern Ontario, and the Dairymen’s

Association of Western Ontario, which were particularly interested in

the cheese industry, and the Ontario Creameries Association, which was

interested in butter manufacture. There were poultry associations, a

beekeepers’ association, and several live stock associations. From time

to time the suggestion was made that the work of these associations, and

that of the Agriculture and Arts Association and of the bureau of

Industries, should be co-ordinated, and a strong department of

Agriculture organized under a minister of Agriculture holding a distinct

portfolio in the Ontario cabinet. Provision for this was made by the

legislature in 1888, and in that year Charles Drury was appointed the

first minister of Agriculture. The bureau of Industries was taken as the

nucleus of the department, and Archibald Blue, the secretary, was

appointed deputy minister.

We have referred to the

reaction that took place in Ontario agriculture after the close of the

American Civil War and the abrogation of the reciprocity treaty. The

high prices of the Crimean War period had long since disappeared, the

market to the south had been narrowed, and the Western States were

pouring into the East the cheap grain products of a rich virgin soil.

Agricultural depression hung over the province for years. Gradually,

however, through the early eighties the farmers began to recover their

former prosperous condition, sending increasing shipments of barley,

sheep, horses, eggs, and other commodities to the cities of the Eastern

States, so that at the close of the period to which we are referring

agricultural conditions were of a favourable and prosperous nature.

The Modern Period,

1888-1912

In 1888 a new period in

Ontario’s agricultural history begins. The working forces of agriculture

were being linked together in the new department of Agriculture. Charles

Drury, the first minister of Agriculture, held office until 1890, being

succeeded by John Dryden, who continued in charge of the department

until 1905, when a conservative government took the place of the liberal

government that had been in power since 1871.

Two factors immediately

began to play a most important part in the agricultural situation: the

opening up of the north-western lands by the completion of the Canadian

Pacific Railway in 1886, and the enactment, on October 6, 1890, of the

McKinley high tariff by the United States. The former attracted

Ontario’s surplus population, and made it no longer profitable or

desirable to grow wheat in the province for export; the latter closed

the doors to the export of barley, live stock, butter, and eggs. The

situation was desperate; agriculture was passing through a period of

most trying experience. Any other industry than that of agriculture

would have been bankrupted. The only hope of the Ontario farmer now was

in the British market. The sales of one Ontario product, factory cheese,

had been steadily increasing in the great consuming districts of England

and Scotland, and there was reason to believe that other products might

be sold to equal advantage. Dairying was the one line of agricultural

work that helped to tide over the situation in the early nineties. The

methods that had succeeded in building up the cheese industry must be

applied to other lines, and all the organized forces must be co-ordinated

in carrying this out. This was work for a department of Agriculture, and

the minister of Agriculture, John Dryden, who guided and directed this

co-operation of forces and made plans for the future growth and

expansion of agricultural work, was an imperialist indeed who, in days

of depression and difficulty, directed forces and devised plans that not

only helped the agricultural classes to recover their prosperity, but

also made for the strengthening of imperial ties and the working out of

national greatness.

The British market

presented new conditions, new demands. The North-West could send her raw

products in the shape of wheat; Ontario must send finished products—

beef, bacon, cheese, butter, fruit, eggs, and poultry—these and similar

products could be marketed n large quantities if only they could be

supplied of right quality. Transportation of the right kind was a prime

necessity. Lumber, wheat, and other rough products could be handled

without difficulty, but perishable goods demanded special accommodation.

This was a matter belonging to the government of Canada, and to it the

Dominion department of Agriculture at once began to give attention. The

production of the goods for shipment was a matter for provincial

direction. Gradually the farmers of the province adapted themselves to

the new conditions and after a time recovered their lost ground. General

prosperity came in sight again about 1895. For several years after this

the output of beef, bacon, and cheese increased steadily, and the gains

made in the British market more than offset the loss of the United

States market. It was during the five years after I890 that the farmers

suffered so severely while adjusting their work to the new conditions.

With these expanding lines of British trade products, the values of

stock, implements, and buildings made steady advance, and in 1901 the

total value of all farm property in the province crossed the billion

dollar mark. Since that year the annual increase in total farm values

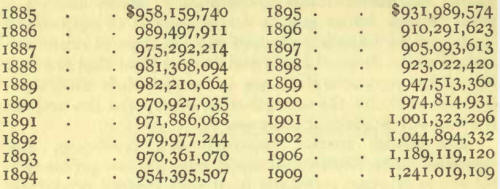

has been approximately forty million dollars. The following statement of

total farm values in Ontario, as compiled by the Ontario bureau of

Industries, the statistical branch of the department of Agriculture, is

very suggestive:

Total Farm Values

From the above table it

will be seen that the closing of the United States markets in 1890 was

followed by a depreciation in general farm values which lasted until

1898, when the upward movement that has continued ever since set in.

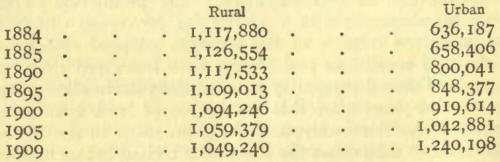

And now let us see how

the population was changing, as to its distribution between rural and

urban, during these years. First, we shall give the assessed population.

The Canadian Pacific

Railway opened up the wheat lands of the West in 1886. At that time the

rural population was nearly double the urban; in 1905 they were about

equal; and six years later the urban population of Ontario exceeded the

rural.

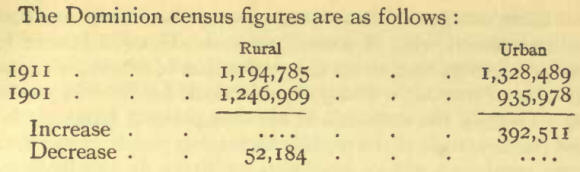

THE MODERN PERIOD

It will thus be seen

that during the past twenty-five years there has been a steady increase

in the consumers of food products in Ontario and a slight decrease in

the producers of the same. The surplus population of the farms has gone

to the towns and cities of Ontario and to the western provinces. Now

for a moment let us follow these people to the West. Many of them have

gone on the land to produce wheat. Wheat for the European market has

been their principal product, therefore they in turn have become

consumers of large quantities of food that they do not themselves

produce but must obtain from farmers elsewhere. But not all who have

gone West have become farmers. The Dominion census of 1911 gives the

following statement of population for the provinces and districts west

of Lake Superior:

The western provinces

are generally considered to be almost purely agricultural, and yet the

percentage increase of urban population has been nearly double the

percentage increase of rural population. And this rapidly growing urban

population also has demanded food products. Their own farmers grow wheat

and oats and barley. British Columbia produces fruit; for her own people

and some surplus for the prairie provinces. There is some stock-raising,

but the rapid extension of wheat areas has interfered with the great

stock ranches. From out of the Great West, therefore, there has come an

increasing demand for many food products. Add to this the growing home

market in Ontario, and, keeping in mind that the West can grow wheat

more cheaply than Ontario, it will be understood why of recent years the

Ontario farmer has been compelled to give up the production of wheat for

export. His line of successful and profitable work has been in producing

to supply the demands of his own growing home marker, and the demands of

the rapidly increasing people of the West, both rural and urban, and

also to share in the insatiable market of Great Britain. Another element

of more recent origin has been the small but very profitable market of

Northern Ontario, where lumbering, mining, and railroad construction

have been so active in the past five or six years.

The result of all this

has been a great increase in fruit production. Old orchards have been

revived and new orchards have been set out. The extension of the canning

industry also is most noticeable, and has occasioned the production of

fruits and vegetables in enormous quantities. Special crops such as

tobacco, beans, and sugar beets are being grown in counties where soil

and climatic conditions are favourable. The production of poultry and

eggs is also receiving more attention each succeeding year. The growth

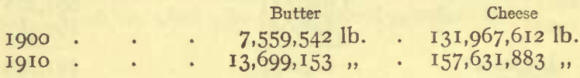

of cities is creating an increasing demand for milk, and the production

of factory-made butter and cheese is also increasing, as the following

figures for Ontario from the Dominion census prove:

For the past ten or

twelve years the farmers of Ontario have been slowly adjusting their

work to the new situation, and the transition is continuing. While in

some sections farms are being enlarged so as to permit the more

extensive use of labour-saving machinery and the more economical

handling of live stock, in other sections, particularly in counties

adjacent to the Great Lakes, large farms are being cut up into smaller

holdings and intensive production of fruits and vegetables is now the

practice. This, of course, results in a steady increase in land values

and is followed by an increase in rural population. The farmers of

Ontario are putting forth every effort to meet the demands for food

products. The one great difficulty that they have encountered has been

the scarcity of farm labour. Men have come from Europe by the tens of

thousands, but they have been drawn largely to the growing towns and

cities by the high wages offered in industrial lines; and the West, the

‘Golden West’ as it is sometimes called, has proved an even stronger

attraction. It seems rarely to occur to the new arrival that the average

farm in Ontario could produce more than a quarter section of prairie

land. Signs, however, point to an increase in rural population, through

the spread of intensive agriculture.

Before referring to the

methods of instruction and assistance provided for the developing of

this new agriculture in Ontario, reference should be made to one thing

that is generally overlooked by those who periodically discover this

rapid urban increase, and who moralize most gloomily upon a movement

that is to be found in nearly every progressive country of the civilized

world. In the days of early settlement the farmer and his family

supplied nearly all their own wants. The farmer produced all his own

food; he killed his own stock, salted his pork, and smoked his hams. His

wife was expert in spinning and weaving, and plaited the straw hats for

the family. The journeyman shoemaker dropped in and fitted out the

family with boots. The great city industries were then unknown. The

farmer’s wife in those days was perhaps the most expert master of trades

ever known. She could spin and weave, make a carpet or a rug, dye yarns

and clothes, and make a straw hat or a birch broom. Butter, cheese, and

maple sugar were products of her skill, as well as bread, soap, canned

fruits, and homemade wine. In those days the farm was a miniature

factory or combination of factories. Many, in fact most, of these

industries have gradually moved out of the farm home and have been

concentrated in great factories; and the pedlar with his pack has

disappeared under a shower of catalogues from the departmental city

store. In other words, a large portion of work once done upon the farm

and at the country cross-roads has been transferred to the town and

city, and this, in some part, explains the modern movement city wards

— there has been a transference from country to city not only of people

but also of industries. Whether this has been in the interests of the

people s another question, but the process is still going on, and what

further changes may take place it is difficult to determine and unwise

to forecast.

And now let us see what

agencies and organizations have been used in the development of the

special lines of agriculture since the creation of the department in

1888. We have stated that the Agriculture and Arts Association had been

for many years the directing force in provincial agricultural

organization. It held an annual provincial exhibition it issued

the diplomas to the graduates of the Ontario Veterinary College; and it

controlled the various live stock associations that were interested in

the registration of stock. Shortly after 1888 legislation was enacted

transferring the work to the department of Agriculture. The place for

holding the provincial exhibition was changed from year to year. In 1879

a charter was obtained by special act for the Toronto Industrial

Exhibition, the basis of which was the Toronto Electoral Agricultural

Society. Out of this came the annual Toronto Exhibition, now known as

'he Canadian National Exhibition, and the governmental exhibition was

discontinued.

The Ontario Veterinary

College was a privately owned institution, though the diplomas were

issued by the Agriculture and Arts Association. The royal commission

appointed in 1905 to investigate the University of Toronto recommended

the taking over of this association by the government, and as a result

it passed under the control of the department of Agriculture in 1908,

and was affiliated with the University of Toronto. Since that time the

diploma of Veterinary Surgeon (V.S.) has been issued by the minister of

Agriculture, and a supplementary degree of Bachelor of Veterinary

Science (B.V.Sc.) has been granted by the university. The taking over of

this institution by the government, the resuming by the province of its

original prerogative, was accompanied by an enlargement of the course,

an extension from two years to three years in the period of instruction,

and a strengthening of the faculty. The herd-books or pedigree record

books were, in most cases, Canadian, and it was felt that they should be

located at the capital of the Dominion.

These have therefore

been transferred to Ottawa and are now conducted under Dominion

regulations.

The Ontario bureau of

Industries was the basis of organization of the department. As other

work was added the department grew in size and importance, and the

various branches were instituted until there developed a well-organized

department having the following subdivisions:

The Agricultural

College,

The Veterinary College,

The Agricultural and Horticultural Societies Branch,

The Live Stock Branch,

The Farmers’ and Women’s Institutes Branch,

The Dairy Branch,

The Fruit Branch,

The Statistical Branch,

The Immigration and Colonization Branch.

Each branch is in

charge of a special officer. In addition to the above there is a lot of

miscellaneous work, which as it develops will probably be organized into

separate branches, such as farm forestry, district representatives, etc.

John Dryden was in 1905

succeeded as minister of Agriculture by Nelson Monteith, who in 1908 was

succeeded by J. S. Duff. Under their care the department has grown and

expanded, and through their recommendations, year by year, increasing

amounts of money have been obtained for the extension of agricultural

instruction and the more thorough working out of plans inaugurated in

the earlier years of departmental organization.

The history of

agricultural work in Ontario in recent years may be put under two

heads—expansion of the various organizations and extension of their

operations, and the development of what may be called ‘field work.’

Farmers’ institutes and women’s institutes have multiplied; agricultural

societies now cover the entire province; local horse associations,

poultry associations, and beekeepers’ associations have been encouraged;

winter fairs for live stock have been established at Guelph and Ottawa;

dairy instructors have been increased in number and efficiency; short

courses in live stock, seed improvement, fruit work, and dairying have

been held; and farm drainage has received practical encouragement.

Perhaps the most important advance of late years has resulted through

the appointment of what are known as district representatives. In

co-operation with the department of Education, graduates of the

Agricultural College have been permanently located in the various

counties to study the agricultural conditions and to initiate and direct

any movement that would assist in developing the agricultural work.

These graduates organize short courses at various centres, conduct

classes in high schools, assist the farmers in procuring the best advise

as to new lines of work, assist in drainage, supervise the care of

orchards—in short, they carry the work of the Agricultural College and

of the various branches of the department right to the farmer, and give

that impetus to better farming which can come only from personal

contact. The growth of the district representative system has been

remarkable: it was begun in seven counties in 1907, by 1910 fifteen

counties had representatives, and in 1914 no fewer than thirty-eight

counties were so equipped. At first the farmers distrusted and even

somewhat opposed the movement, but the district representative soon

proved himself so helpful that the government has found it difficult to

comply with the numerous requests for these apostles of scientific

farming. Approximately $125,000 is spent each year on the work by the

provincial government, in addition to the $500 granted annually by the

county to each district office. The result of all this is that new and

more profitable lines of farming are being undertaken, specializing in

production is being encouraged, and Ontario agriculture is advancing

rapidly along the lines to which the soils, the climate, and the people

are adapted. A study of the history of Ontario agriculture shows many

changes in the past hundred years, but at no time has there been so

important and so interesting a development as that which took place in

the opening decade of the twentieth century.

The O.A.C. Review

(Ontario Agricultural College)

For 72 years, from

1889-1961, this magazine was published annually by and for students of

the Ontario Agricultural College. It provides a rich source of

historical information about the department and its alumni as well as

the social and agricultural history of Ontario. Regular columns from the

Ontario Agricultural College and the MacDonald Institute for Women

provide ongoing commentary on student life, detailing the academic,

athletic and social events of each year. Feature articles address the

scientific, social and political issues of the day, through the Great

Depression and two World Wars. Photographs, special reports and

advertisements enhance the historical richness of this publication.

Material for this collection is provided by the University of Guelph

Library.

I selected a random

copy for you to read here...

Volume 20 Issue 7 December April 1908

The highlight of this special number are articles on agricultural

education in the rural schools of Ontario and the need for qualified

instructors. Other articles address the obligations of Canadian

citizenship, the co-operative movement in Ontario, the need to improve

school grounds in Ontario, and current research on farm crops and

vegetables. An article regarding the Women's Art Association of Canada

is in the Macdonald Institute column. Alumni news and wedding

announcements are available in the Our Old Boys column.

I also looked for the

earliest issues and found that volume 17 was the earliest they had

available in the archive so selected the issues available under that

volume to give you some additional reading...

Volume 17 Issue 2, November 1904

This autumn issue's articles are regarding the scarcity of farm labour,

mosquitoes, the best feed for pigs; housing for poultry, the cultivation

of carnations, and Canadian literature. A Japanese student at the O. A.

C. contributed an article on the Russo-Japanese War. Campus articles

pertain to the activities of the Y. M. C. A., Literary Society, and the

Field Day results. The Macdonald Institute section highlights the

Halloween dance and activities of its alumnae. Alumni news is available

in the Our Old Boys column.

Volume 17 Issue 3, December 1904

This Christmas issue continues the article on the Russo-Japanese War.

Student articles pertain to a student's travels through England, the

study of agricultural economics, and Canadian poetry. Professor Zavitz

contributes an article on European and North American agricultural

colleges. Professor Reynolds writes of his experimental shipment of

fruit to Winnipeg using cold storage. Other agricultural articles are

regarding beneficial winter birds and Christmas markets for beef,

poultry, and swine. Horticultural articles address the beauty of farms,

cultivation of chrysanthemums, and a review of the Provincial Fruit,

Flower and Honey Show. The Macdonald Institute column reports on the

completion of the Macdonald Institute and students who attended the

World's Fair in St. Louis. Campus articles report the activities of the

Ontario Agricultural and Experimental Union, the Literary Society's mock

parliament, students who won prizes at the Winter Fair, and athletic

activities. Alumni news is available in the Our Old Boys column and

features the tenth anniversary of the freshman class of 1894.

Volume 17 Issue 4, January 1905

This issue continues the Japanese student's article on the

Russo-Japanese War. Professor Reed contributes an article on the future

of horse breeding. A guest article suggests an alternative educational

curriculum for boys. The agricultural articles pertain to International

week at the Union Stockyards, the use of artificial fertilizers, and

cover crops for orchards. Campus articles include reports on the Ontario

Agricultural and Experimental Union and athletic activities. The

Macdonald Notes report on the re-opening of Macdonald Hall and the

Macdonald Literary Society. Alumni news is available in the Somewhat

Personal column and mentions the formation of the Maritime O. A. C. Boys

Association.

Volume 17 Issue 5, February 1905

This issue contains articles on agricultural education, progress in

forestry, and markets for agricultural exports. An article on the farm

labor problem suggests that the solution is the elimination of fencing.

The Ontario Agricultural and Experimental Union reports on its 1904

dairy experiments. Agricultural articles pertain to starting a poultry

business, Canadian grown bananas, refrigerated transport of fruit crops,

and tree grafting methods. Campus news reports are included in the

College Life and Athletics columns. The Macdonald Notes column speaks to

the advancement of the study of domestic science. Alumni news is

available in the Somewhat Personal column.

Volume 17 Issue 6, March 1905

This issue has guest articles regarding agricultural transportation,

Canadian literature, and agricultural education in the public schools.

Agricultural articles pertain to foreign markets for Canadian produce,

the quality of grain seed, and the food science of the quality of

western wheat. Horticultural articles address the cultivation of

Primulas and the farm garden. The Ontario Agricultural and Experimental

Union article reports the 1905 co-operative experiments in agriculture.

Campus articles report the activities of the Literary Society, Y. M. C.

A., and athletics department. The Macdonald Notes provides an update on

the practical training of housekeepers and the Macdonald Literary

Society. Alumni news is available in the Our Alumni column.

Volume 17 Issue 7, April 1905

This issue received guest articles on agricultural societies in Ontario,

and modern seed testing. Professor Lochhead wrote an article on how