|

Civilized man lives in

houses, and as the house that does not contain wood in some form is

practically unknown the lumber industry accompanies civilized man in all

his migrations and progress. It was, in fact, a condition of his

migration and advancement until the railroad brought forest and prairie

together and made habitable the barren places of the earth. A treeless

world might not be uninhabitable, but it is a historical fact that

migration, racial progress and growth of population have been guided by

the forest distribution of the world—modified, of course, by other

conditions, but having that as one of their chief controlling

influences.

The early history of

civilization proves that countries which are now treeless and,

therefore, thinly populated were once blessed with forests. The history

of ancient Persia, Assyria and Canaan would be vastly different from

what it is if those countries had been in their early days in the

forestal condition they are now; or it might be more correct to say that

they would have had no history. The disappearance of the forests led to

the disappearance of the people; and, as today they are barren and

almost depopulated because of the absence of the forests, if the forests

had never existed their prominence in the history of civilization would

have been withheld from them.

Wherever the cradle of

the Aryan peoples may have been, their migrations led them by forest

routes to forest countries, and it was not until recent times that the

plains attracted them. This is true because shelter and fuel were

necessities, which only the forest could furnish. As history goes, the

discovery of coal is but of yesterday. Coal was undoubtedly known to the

ancients, but it became an article of commerce not more than eight

hundred years ago, and it was not until the discovery of the steam

engine in 1705 that coal mining assumed important proportions. Until the

Nineteenth Century coal in most countries was either a luxury or was

used for industrial purposes, while the fuel of the people was wood.

Therefore there was an immediate dependence upon the forests which

relaxed only when transportation—ample enough and cheap enough—linked

the forests and the plains together. It was the railway that finally

made habitable the treeless portions of the earth.

Dreamers have wondered

what would have been the history of North America if the location of the

forests and treeless plains had been reversed—if the discoverers and

explorers sighting the shores of the Atlantic and the Pacific had found

nothing but prairies, no matter how rich the soil—whether settlement

would have awaited the invasion of the railroad. Happily such was not

the case, but however inhospitable the climate and severe the aspect of

the rockbound shores of New England in other respects the trees waved a

welcome and promised shelter and warmth. So, whether the early

discoverers were English, French, Spanish or Dutch, they found habitable

shores and were able to establish their colonies in Florida and

Virginia, on the Hudson, on Massachusetts Bay, on the St. Lawrence, on

the coast of Nova Scotia, at the mouth of the Mississippi, in Central

and South America and later on the Pacific shores.

From the coast,

migration and settlement drifted inland, following the course of the

rivers or striking boldly across the country, but always protected and

supported by the forests. Whether we consider the individual pioneer

with his family or the congeries of population, the villages and cities,

all were in earlier days absolutely dependent upon the forests and

endured separation from them only by the aid of commerce.

The first colonies in

North America were, for the most part, made up of men of every trade and

profession, but their development and the extension of their boundaries

must be credited to the pioneers who struck off into the forest, a

little removed from their fellows, and there hewed out their homes.

These men combined in themselves all of the practical trades. They were

hunters and fishermen as well as farmers; they were their own

carpenters, blacksmiths, millers, tanners, shoemakers and weavers, and

all of them were emphatically, at the beginning of the settlement,

directly dependent upon the forest which gave them their material for

building and for the simple implements of the time, their fuel and even

their food. Yet, in a sense, the forest was their enemy, for they had to

clear it away to make room for wheat and corn. The settler on American

shores was the first American lumberman. He was a lumberman by

necessity, as he was a carpenter, shoemaker and weaver. So the history

of the lumber industry—for the lumber trade as a branch of commerce was

a later development—is the history of progress, of settlement and of

civilization.

As population increased

and as the centers of population enlarged in importance, there came

about a sharp differentiation and a natural apportionment of work; and

so the lumber industry, which at the beginning merely supplied the needs

of the individual settler in the forest, came to supply the requirements

of the young towns and the cities of the continent. This was, however, a

small matter, for all along the Atlantic coast, the shores of the Gulf

of Mexico and on the banks of every tidal river the trees grew in

profusion. Every village could be supplied from its own immediate

resources. It was only when the increase in population made the

requirements so great that local supplies were exhausted that a lumber

industry that looked beyond the immediate neighborhood of its mills for

the disposal of its product was either needful or possible. As the first

settlers were the first lumbermen, so the first settlement was the first

site of the lumber industry in America.

From the date of

Columbus’ first voyage in 1492, for more than a hundred years the

process was discovery and exploration and conquest rather than genuine

settlement. By the end of the Fifteenth Century the eastern coast of the

three Americas had been roughly outlined. Columbus, the Cabots, Pinzon,

Cabral, Cortereal, Vespucci, Balboa and others had cursorily examined

the coast all the way from Hudson Strait to the vicinity of Bahia, on

the eastern coast of Brazil. The lands discovered were usually claimed

for the crowns which the voyagers represented and some of these claims

were made good by colonization.

The next century was

one of combined discovery, exploration, conquest and occupation. By its

conclusion the coasts of both oceans had been well outlined and the

general character of the countries determined. However, as late as 1600

there had been little genuine colonization, the only successful attempts

at occupation being by the Spaniards and Portuguese, and these

accomplishments were confined chiefly to the West Indies, Central

America, the Isthmus of Panama and isolated portions of South America.

Until the Seventeenth

Century, North America, which was destined to exceed all the others in

population and wealth, remained practically virgin soil. For example,

the Gulf of St. Lawrence was entered by Gaspar Cortereal in 1500, and

Cartier voyaged up the St. Lawrence as far as Montreal in 1535, but it

was not until the middle of the century that any attempt at colonization

within the present limits of Canada was made and not until 1608 that

Quebec was founded.

A brief summary of some

of the leading dates and names during the period of exploration may be

pardoned. Columbus’ first voyage, in 1492, resulted merely in the

discovery of some of the West Indies, including Cuba, which he thought

to be mainland. In 1493, seven weeks after the return of Columbus to

Spain, Pope Alexander VI. assigned the lands discovered and to be

discovered west of a certain line to Spain, and east of the same line to

Portugal. This line was a great circle passing through the poles, and

the following year was defined as passing 370 leagues west of the Cape

Verde Islands. This edict was the basis of the Portuguese claims in the

eastern part of South America and led to the Portuguese sovereignty over

Brazil and its colonization by that power. It also led to a division of

authority in the antipodes. The second voyage of Columbus, in 1493,

resulted in further discoveries in the West Indies, including Jamaica.

In 1498, on his third expedition, Columbus discovered Trinidad and

coasted along the delta of the Orinoco and thence to the west. He set

out on his fourth voyage in May, 1502, and during the following year he

studied the coasts between the gulfs of Honduras and Darien.

In the meantime other

navigators had been at work and other governments than that of Spain

became interested. The English were early engaged in western

explorations, and in 1497 Henry VII. sent out John Cabot, an Italian

navigator, accompanied by Sebastian Cabot, his son, who planted the

English flag on an unknown coast supposed to have been that of Labrador.

The following year the two sailed as far south as Cape Florida and are

supposed to have been the first to see the mainland of America. Nearly

thirty years thereafter, in 1526, Sebastian Cabot, in the employ of

Spain, began a voyage during which he discovered La Plata River and

erected a fort at San Salvador, now Bahia.

In the same year that

the Cabots began their work of exploration, 1497, Pinzon, Vespucci and

others sailed from Cadiz. They are supposed to have first touched the

coast of Honduras, whence they followed the coasts of Mexico and the

United States, rounding Florida, and are believed to have sailed as far

as Chesapeake Bay. In 1499 Vespucci with others followed the northern

coast of South America for a long distance, including the coasts of

Venezuela, the Guianas and part of the coast of Brazil. In 1500 Pinzon

struck the Brazilian coast near the site of Pernambuco and discovered

the Amazon. During a period of about three years, beginning with 1500,

Gaspar and Miguel Cortereal made voyages in the interest of Portugal to

the north coast of North America, but mainly within the region

previously explored by the Cabots.

Thus early in the

beginning of the Sixteenth Century not much more had been done than to

arouse the interest of the western countries of Europe in those unknown

lands to the west, which were still supposed to be parts of Asia, for it

was not until 1513 that Balboa discovered the Pacific and not until 1519

that Magellan passed through the straits that bear his name and thus

discovered the long sought western passage to the Indies, a passage

which had been sought on the north by the Cabots and by numerous

explorers at every gulf along the entire eastern coast.

Exploration proceeded

rapidly thereafter. Ponce de Leon discovered Florida in 1512. In 1524

Verrazani explored the coasts of Carolina and New Jersey and entered the

present harbors of Wilmington, New York and Newport. During 1539,1540

and 1541 De Soto explored Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi, and

discovered the Mississippi River in the last year. In 1542 and the

following year Cabrillo sailed along the Pacific Coast. In 1562 Ribault

attempted to plant a Huguenot colony at Port Royal, Carolina, but it was

abortive. Another Huguenot colony was attempted on St. Johns River,

Florida, in 1564, by Laudonniere. It was destroyed by the Spaniards, but

the following year, 1565, Menendez established St. Augustine, Florida.

During the three years beginning with 1578 Drake made his famous

explorations along the Pacific Coast, reaching as far north as Oregon,

though he had been preceded by the Spanish (Cabrillo, 1542). The Spanish

had been busy on the southern borders and in 1582 Espejo founded Santa

Fe, New Mexico. In 1584 and 1587 Raleigh attempted to plant colonies in

Virginia, but it will be seen that until the beginning of the

Seventeenth Century there were but two settlements within the present

boundaries of the United States, both made by the Spanish.

The exploration of

Central America and the Isthmus of Panama proceeded rapidly during the

early part of the Sixteenth Century and settlement followed closely on

exploration. It should, however, be stated that colonization in its

proper meaning was seldom attempted. Military and trading posts were

established and maintained and these posts gradually grew into colonies

with entities of their own. Closely following the taking possession of

the Isthmus and Central America occurred the conquest of Mexico, in

which Spanish authority was established by Cortez in 1521, and Mexico

became a vice-royalty in 1535. It is, perhaps, worth mentioning that the

city of Belize, British Honduras, was a settlement by Wallace, a Scotch

buccaneer, and the chief occupation of its people was wood-cutting, or

the lumber business, and this business was early in the Eighteenth

Century a subject of dispute.

Taking up in outline a

review of the discovery and settlement of South America: The coast of

Colombia was one of the earliest portions of America to be visited by

the Spanish, but the first settlement was at Nombre de Dios, on the

Isthmus, in 1508, and by the middle of the century Spanish power was

fairly established and flourishing communities had arisen.

Venezuela was made a

captain-generalcy in 1550. The coast of Brazil was a favorite field of

early exploration by the Portuguese and by 1508 the coast had been

outlined, for in that year Vincent Pinzon entered the Rio de la Plata.

Amerigo Vespucci explored the coast under royal authority and enormous

grants were made to persons who were willing to undertake settlement.

Each captaincy, as these divisions of the territory were called,

extended along fifty leagues of coast. But settlement was not attempted

until about 1531.

The Argentine Republic

was first visited by De Solis, in 1516, and in 1535 Mendozo attempted

the establishment of Buenos Ayres, but it was not until 1580 that it was

successfully accomplished.

The history of Uruguay

dates from 1512 with the exploration and landing of De Solis, but no

settlement was made until the Seventeenth Century. The coast of Peru was

first visited in 1527. The conquest of Peru was accomplished in 1533,

and the city of Lima was founded in 1535 by Pizarro.

The first Spanish

invasion of Chili was in 1535 and 1536, at which time the city of

Santiago was founded.

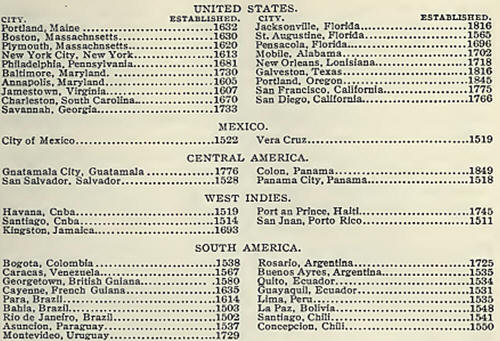

This brief review of

early settlement may well be concluded by a list of some of the leading

cities of the Americas and some of the earliest settlements, with the

accepted dates of their establishment or occupation by Europeans.

What did the original

explorers of the coasts of America discover in respect to the forests?

They found a wooded coast from the Strait of Belle Isle, 52 degrees

north latitude, to the mouth of the Rio de la Plata, 35 degrees south

latitude, practically without a break. The forest fringed the shores for

that enormous distance, spanning nearly one-fourth of the earth’s

circumference and much augmented by the many and great indentations of

the shore line. But what lay back of the wooded shores? For the most

part a solid forest extended inland, in some places for two thousand

miles. Notwithstanding the great areas of arctic muskeg in the north,

the barren plains and mountains of the extreme south and the great

treeless areas between—the prairies, the pampas, the llanos—and

notwithstanding the areas lifted high above the treeline by the Rockies,

the Sierras and the Cordilleras, the western continent was one of

forests. It is difficult to define the treeless areas and to say exactly

what percentage of the area of any one country or state was wooded or

treeless, but in an approximate way some general facts may be stated.

Canada was and is a

forested, or rather a wooded, country. Botanists, geographers and

students of economics note a difference between forested and wooded

areas. The forests yield timber of commercial value, but the wooded

areas offer a welcome and means of livelihood to the settler. The total

area of Canada, excluding Newfoundland and Labrador, is estimated at

3,745,574 square miles. Of this great area 1,351,505 square miles is

estimated to be still wooded. It is probable that the original wooded

area of Canada was about 1,690,000 square miles. All of the arctic

territory of Franklin, estimated at 500,000 square miles, and parts of

Yukon and Mackenzie and more than half of Keewatin are and were

treeless, owing to the influence of their arctic climate. The Labrador

Coast and the northern part of Ungava are also largely or wholly

treeless. There are also the great prairies of Assiniboia, Saskatchewan

and Alberta. Not considering the areas which are treeless because of

their northern latitude, fully ninety percent of Canada was wooded.

Newfoundland’s coast was forbidding, but its interior was heavily

wooded.

What is now the United

States presented an almost solid and continuous forest from the Atlantic

to the Mississippi River and in places still farther west; and then,

after an interval of treeless plains, came the mountains with their

forest groups and beyond them the wonderful arboreal wealth of the

Pacific Coast. The total land surface of the continental United States,

excluding Alaska, is 2,972,594 square miles. It is estimated that the

present forest area is about 1,000,000 square miles; but, combining the

fragmentary records that are to be found and estimating areas from the

history of settlement and of agricultural development, as well as by the

effect produced by the lumbering industry, it can be asserted with

confidence that the original forested area of the present United States

was at least 1,400,000 square miles, or nearly one-half of the entire

land area.

Alaska has an area of

about 591,000 square miles. Its wooded area, some of which is densely

covered with large timber, can be safely estimated at about 100,000

square miles, while a much greater area is covered with brush.

The total area of

Mexico is 767,000 square miles, of which about 150.000 square miles are

of woodland. The area of Central America is 163,465 square miles, of

which about 100.000 square miles is estimated to have been forested.

South America has for

the most part a climate favorable to tree growth mainly of the tropical

sort, due to its peculiar formation. The important mountain system of

the continent lies close to the Pacific Coast, and in it many rivers

which empty into the Atlantic Ocean or the

Caribbean Sea have

their rise. The eastern trade winds sweep over the continent, depositing

moisture as they go, but are finally exhausted by the Andes and the

other great mountain systems of the western coast. Thus the abundantly

watered interior of the continent north of the Paraguay River is largely

forested. There are exceptions in the llanos of the Orinoco and in some

of the tablelands of the west, and Argentina is largely open grass land

or barren plains. The total area of South America is estimated at about

7,685,000 square miles. A careful review of the conditions in each

country leads to the conclusion that of this total area at least

6,000,000 square miles are naturally wooded. The great western ranges

lift themselves above the treeline, the extreme southern part of the

continent is almost antarctic in its characteristics and there are some

naturally treeless plains, but, as noted above, approximately seventy

percent of the area is wooded and the vast stretches of forest are of

the most luxuriant kind. The growth of vegetation in South America is

the most varied and the heaviest to be found in the world. Even in

Africa only comparatively small and isolated portions compare with it.

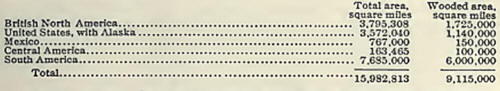

Summing up the Americas

we find the following results in total area and wooded area:

Consequently, of the

total area of the New World, more than fifty-five percent was covered

with forests, which were most dense on the eastern coast, the one first

approached by discoverers and explorers. The forests ranged from the

light and easily worked woods of general utility of North America, such

as the white and yellow pine, to the heavy and hard woods of the tropics

and semitropics, adapted to multitudes of uses according to their

qualities of beauty in color and grain and their adaptability to

ornamental use, or as dye stuffs. Hence, the lumber industry was

practically the first to be established and to form the basis of

eastbound commerce across the Atlantic. Before grain, cotton, furs or

even tobacco were exported from the Americas, lumber and timber had

already established themselves in the favor of the Old World, and many

of the explorers who were searching for gold returned with wood.

These subjects, both

from historical and present statistical standpoints, will be treated

under the heads of the countries, states or provinces concerned. In

taking up the more detailed account of the origin and development of the

lumber industry it has been deemed best to treat the subject not

entirely chronologically but to a certain extent geographically and with

regard to its present magnitude and highest development. Thus, beginning

with North America, and in that continent governed somewhat by

geographical relations, first place is given to the British possessions.

If a chronological arrangement had been determined upon, undoubtedly

preference would have been given to Central America and the northern

part of South America. Again, in North America proper the industry might

be supposed to have witnessed its first development in connection with

the oldest settlements. Such undoubtedly was the fact, but St.

Augustine, and Florida as a whole, for hundreds of years played but a

minor part in the forestal development of the continent and little or no

part in international commerce. The early English settlers in Virginia

were comparatively little concerned about wood. It was on the

northeastern coast of the United States and in the Maritime and

Laurentian provinces of Canada that the lumber industry early reached a

high development and first became an important element in international

trade. Geographical considerations and the further fact that within

Canada lie the northern boundaries of the tree growths of the continent

constrain us to take up first Canada rather than the United States, and

the Maritime provinces rather than Maine. |