|

Before entering into a

minute discussion of the timber resources and the lumber history of

Canada, it is well to review briefly the North American continent in its

relation to tree distribution, especially with reference to the United

States and Canada, which countries are one in their forest

characteristics. While there is one prominent tree species which is

almost wholly confined to Canada, and a few others whose native habitat

is largely within its area, and while about half of the tree species of

the continent, belonging to the southern United States, do not appear

north of the international boundary, that arbitrary line of demarcation

between the two countries cuts across the mountains, the treeless

plains, the forested areas and the lines of tree growth; so that in a

discussion of tree distribution the two countries should be treated as

one, the differences being determined by soil and climatic conditions

which have no relation to political divisions.

It should be noted

first that the Atlantic Coast, including its islands, is practically all

timbered from the Strait of Belle Isle, or certainly from the northern

boundary of the main body of Newfoundland, to the Strait of Florida. The

treeline follows the Gulf Coast from near the southern point of Florida

to about west of Galveston, Texas, so that the Gulf and Atlantic coasts

of the United States, with small exceptions, are timbered.

As the northern arm of

Newfoundland is practically barren, so is the Labrador Coast. Starting

from the Strait of Belle Isle, the northern forest limit runs a little

inland from the coast, following the boundary between Labrador and

Ungava to Ungava Bay; thence bending westerly and southerly it strikes

Hudson Bay at about 57 degrees north latitude. The northern limit on the

western side of Hudson Bay begins farther north, at about Fort

Churchill, and follows an approximately straight line northwestward,

passing north of Great Slave Lake, to the mouth of the Mackenzie River,

north of the Arctic Circle; thence it turns to the southwest through

Alaska, striking the coast again in the southwestern part of that

American territory.

The Pacific Coast of

North America has characteristics quite different from those of the

Atlantic Coast, owing to the mountain uplift which closely follows the

coast. Instead of a solid and wide body of timber, as is the condition

on the Atlantic Coast, there are smaller areas heavily timbered,

intersected and separated by mountain areas which are nearly or quite

treeless. The presence of the "mountains further results in a semiarid

condition farther inland. Practically all the way from Cook Inlet, in

Alaska, to the Bay of San Francisco, the coast has a continuous fringe

of heavy forest growth, widening out as local topography will permit

into the great forests which are found in British Columbia, Washington

and Oregon.

The western mountain

and plateau country of the continent is more or less timbered

throughout, barren plains being crossed or bounded by forested mountain

slopes, or the barren mountains of the North being penetrated by

tree-lined valleys. This condition obtains, with variations due

principally to latitude, all the way from the Alaskan peninsula to the

Gulf of Tehuantepec.

Between the widespread

and comparatively solid and uniform forests of the East and the broken

and varied forests of the West lies the great, almost treeless, interior

plain of the continent. The boundaries of this treeless plain may be

thus roughly outlined: Starting from Galveston, Texas, the line runs in

an approximately northern direction through the eastern part of Texas

and the western part of Indian Territory. Thence it turns eastward,

crossing the southeastern corner of Kansas, thence across Missouri,

thence bending into Illinois and reaching just beyond the Indiana line.

Thence in a curve it turns to the north and northwest, striking the

Mississippi River in northern Illinois, leaving it in southern

Minnesota, and passes north between Red Lake and the Red River of the

North. Crossing the international boundary in a northerly direction, it

sweeps around Winnipeg to the northwest and strikes about the

northwestern corner of Manitoba. Thence northwesterly and westerly it

crosses Saskatchewan and northern Alberta, and then, turning again to

the southwest and south, follows the line of the Rocky Mountains back

along the western border of Alberta, across Montana, Wyoming, Colorado

and New Mexico, to and across the Mexican border. West of the latter

part of this line is the broken mountain flora previously described.

Within this great

interior plain are trees, but few forests, so that in a general way the

line described surrounds the great agricultural and grazing section of

the continent, the rich agricultural regions east of the prairies having

been won from the forest through more than a century of settlement and

development.

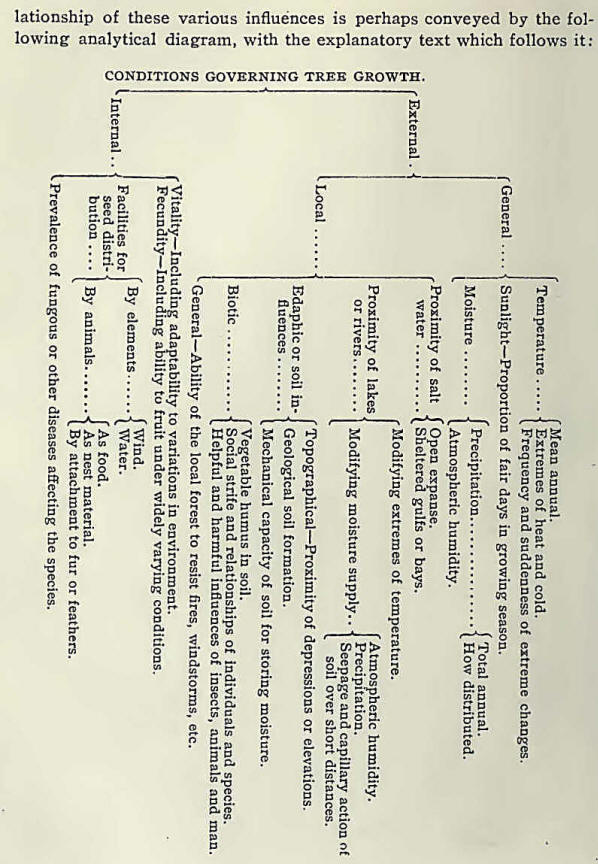

|