|

Almost since the

beginning of timber and lumber exportations from Canada the

manufacture of cooperage stock or material therefor has been one of

the leading of the minor forest industries. Easily accessible to

waterways, all the way from Quebec to Lake Huron were originally

immense quantities of # timber suitable for this purpose. The oaks,

and other woods used in the manufacture of cooperage stock, which

grew in Canada compared very favorably with those of the United

States, and, as intimated above, they were for the most part more

accessible, though for scores of years the industry in the United

States has been growing to magnificent proportions, feeding upon the

resources reached not only by river, but by railroads. The Canadian

cooperage stock industry, however, antedated that of the United

States and was maintained in large proportions until the cutting

away of timber compelled a reduction in its magnitude.

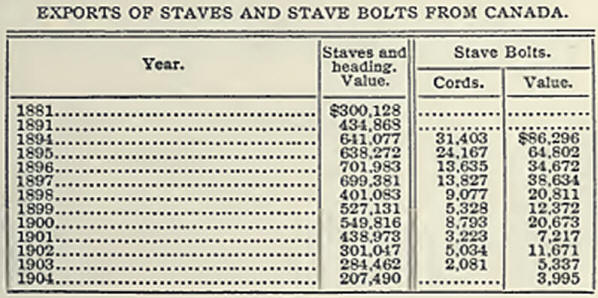

The more recent

history of the Canadian industry is indicated to some extent in the

figures of production contained in the preceding chapter, but a more

reliable measure of its importance and fluctuations is found in the

export statistics, out of which the following brief table has been

compiled. The maximum of exportations, and presumably of manufacture

likewise, was reached about the middle of the last decade, since

when there has been an almost uniform decline, until, in 1904, the

total exports of staves, heading and stave bolts were valued at only

$211,485.

The cooperage stock

industry of Canada is not of sufficient importance to demand much

space in this work, but a few pages may well be devoted to a review

of the industry from historical and technical standpoints, prepared

by a man who is one of the leading exporters of this class of

material either in Canada or in the United States. His review of

this subject1 occupies the remainder of

this chapter:

A great many years

ago, when the principal exports from Canada to the old country

consisted of furs and timber, some enterprising Frenchman (or

possibly Scotchman), who had come from the motherland, being

employed in the manufacture of barrels and casks, conceived the idea

of getting out staves and heading in Canada for export to Great

Britain. In those days the forests contained a great deal of fine

white oak all the way from Quebec to Windsor, but more especially in

the western peninsula, and those trees were cut down, squared up

with a broad-ax and shipped to England, the consequence being that

only the finest trees were used and only part of them, namely, the

part that could be put into square timber.

This square timber

was floated down to Montreal, loaded on vessels there for the old

country, where it was used for the manufacture of lumber, and, I

presume, staves also. This enterprising Frenchman or Scotchman no

doubt saw the terrible waste which occurred by only using certain

parts of the trees, and also saw the trees which were passed as not

fit for square timber, but which would make excellent staves and

undoubtedly this was the commencement of the cooperage industry in

Canada.

Staves were taken

out for the wine casks of France and Spain, and the whisky casks of

Great Britain and Ireland, and before long “ Canada butts ” and “

Quebec pipe staves ” became standard grades in Great Britain and on

the Continent.

At that time all of

the sugar used in England came from the West Indies and was shipped

in hogsheads, and the West Indies hogshead staves were also

manufactured in Canada, shipped to England, where they were made

into shooks and sent over to the West Indies to be filled with

sugar, molasses and rum.

As the oak got

scarcer in the east, the hewers and stave makers drifted west, until

Chatham, Ontario, became one of the great centers of the stave

industry.

The old residents

here have told the writer that years ago McGregor Creek and Thames

River, which converge at Chatham, would have its waters covered for

miles every spring with square oak, walnut timber, Canada butts,

Quebec pipe staves and West India hogshead staves, and the smaller

and shorter pieces of oak, utilized for barrel keg staves and

heading. These were loaded on vessels in the Thames River, sent down

to Montreal, and in some cases sent direct to England from Chatham.

This, of course, was entirely tight barrel stock, as in those days

no slack barrel stock was exported from Canada, as being all made by

hand it was too expensive to send over to the old country, which at

that time was almost entirely supplied with norway fir staves and

beech staves made from the timber growing in England, Ireland and

Scotland.

Mr. Neil Watson, of

Mull, Ontario, now a manufacturer of slack barrel stock, hauled

staves from Harwick township to Buckhom Beach for years and sold his

pipe staves, 60x5x2, at $25 per thousand, and West India staves,

44x4^xl, at $5 to $8 per 1,200 for shipment to England.

Tight barrel stock

in Canada is now almost a thing of the past, the oak having been

almost exhausted, and what staves are made here now are used

entirely for local consumption, either being made in the old way,

which I will describe, or being sawed on a drum saw.

The method of

manufacture in the early days, in fact it is still in use, was to

cut the trees up into bolt lengths, according to the quality of the

tree, whether suitable for long or short staves or heading, then to

split these bolts with afrowknife, and in some cases, such as “

Canada butts,” dress them with a draw knife and ship them in the

rough, sometimes taking the sap off, but other times shipping them

with the sap on. Now most of the oak staves are sawn on a drum saw,

which does away with a great deal of waste, on account of the slips

on the part of the workman with the frow, and also enables the

manufacturers to use tougher oak and timber which would not split

freely with a frow, in fact, work up everything very close. The

bucker, for bucking staves, never got much of a foothold in Canada,

as the timber was practically exhausted here before buck staves were

salable on foreign markets.

Oak heading,

instead of being split now, is sawed, and while in the old days the

head used to be split, finished off with a draw knife, marked off

with a compass and sawed out by hand, the bevel also being put on

with a draw knife, the heading is now sawed on a swing saw, piled in

the yard to dry, put through a kiln when partially seasoned, run

through a planer and turned up with a rounding machine, which puts

on the bevel and turns the head at the same time. As already stated,

the manufacture of tight barrel stock in Canada from oak is now

almost a thing of the past, and does not figure very much in the

export trade of Canada.

We will now turn to

the manufacture of slack barrel stock. Years ago when the

manufacturing industries in Canada were in their infancy and the

consumption of barrels was a very minor matter, coopers made their

staves and heading for flour and other slack barrels in the same

manner as they used to make their tight barrel stock, in fact the

same as a great many tight barrel staves and heading are still made

in the United States.

The cooper would

get his bolts in the winter, haul them to his cooper shop, split out

his staves with his frow, and in the winter make the staves with a

draw knife, jointing them on a planer jointer, in some cases even

putting on the joint with his draw knife. At that time slack barrel

staves were made almost entirely from red oak and basswood, the

cooper making his staves during the winter months in his shop,

seasoning them inside his barn or cooper shop, and making up his

barrels as required, and after the staves were seasoned selling them

from seventy-five cents to $1 each. Coopering at that time was

simply a side issue, the cooper being also a farmer, carpenter, or

some other tradesman, and making all kinds of barrels and casks from

a flour barrel to a water tank.

Years rolled on,

the red oak forests of Canada became a thing of the past—what oak

was left would bring very much higher prices for lumber or bending

purposes, sawn timbers, etc., than it would bring for staves, and

the same applied to the States of New York, Ohio and Indiana, which

at that time were large stave producers. Some Yankee genius (sad to

say, unknown), possibly a man who thought there was a great waste of

energy in making staves by hand, got his brains to work and invented

the modern stave knife for cutting slack barrel staves from steamed

bolts. The machine as at first invented is practically the same as

is in use at the present time, the only improvements that have been

made being that the machine is made twice as heavy as formerly, so

as to be rigid and do away with the cutting of thin staves, and a

balance wheel was put on so as to make the strokes more regular, and

the speed increased from fifty revolutions per minute, which was the

original cut of the machine, to 150 or 160 revolutions per minute,

which is the speed at which the modern stave knives are run.

When this machine

was first in use the staves were made entirely from red oak and

basswood, the bolts being split out with a frow or ax, brought to

the mill in this way and cut into staves. Immense elm forests then

attracted the attention of some of the stave manufacturers and they

experimented with making elm staves. It is not a great many years

ago, only since I came to this country, that red oak staves were the

principal kind used on the Minneapolis market, now elm is almost

entirely used, in fact red oak staves are not liked on account of

being so hard to work.

For a great many

years nothing but split bolts were used, until some manufacturer,

with a sawmill attached, conceived the idea of sawing his bolts, but

until fifteen years ago staves made from sawn bolts commanded a

lower price than staves from split bolts, as the coopers were of the

opinion that staves could not be made straight grained unless the

bolts were split, and it took a great many years to remove this

erroneous idea. Now there is hardly a mill in the country making

staves from anything but sawed bolts, and elm is the principal

timber used, in fact is considered always desirable to any timber at

the present time, although birch, beech, maple and southern woods

are now crowding elm by degrees off the market, on account of the

high price of elm stumpage.

We will now turn to

the hoop industry. Until about twenty years ago all of the barrels

were hooped with what is known as half-round hoops. The cooper cut

these hoops in the winter, hauled them to his cooper shop, and spent

the long winter months when not making staves in making hoops for

his summer trade. Then the racked hoop made from black ash came into

vogue, this being the precursor of the modem patent cut elm hoop.

For a great many years the hoops were made either racked or split

from elm, and finished with a draw knife, until the idea was

conceived of cutting the hoops the same as staves from elm plank,

and this hoop was found, when it was perfected, to be superior in

every way to the racked or bark hoop. It is still the principal hoop

on the market, although on account of the scarcity of elm a great

many wire hoops are being used to supplement the elm hoops on the

barrels. The iron hoop alone does not give sufficient rigidity to a

barrel, and if not supplemented with the patent hoop, the barrels

when stored on the bulges would collapse without the assistance of

the elm hoop.

Heading, which

formerly used to be made in the same way as staves, split from

bolts, dressed off with a draw knife, in fact the same as tight

barrel heading, are now sawed on a swing saw, kiln dried and turned

on a turning machine, at the rate of 3,000 sets per day to one

machine, whereas formerly it was a very good cooper who would turn

out twenty-five heads in a day.

While the tight

barrel cooperage industry of Canada has declined, the slack barrel

industry has leaped up until it is one of the most important

industries in Canada, millions of dollars being invested in stave,

hoop and heading mills all over the country from Nova Scotia to

Ontario, and barrels being used for almost every conceivable

purpose, as they are the handiest, strongest and best package that

has yet been invented by man.

There is no doubt

but there is timber in parts of Canada which are yet undeveloped to

continue this industry for a number of years, and no doubt before

the supply is exhausted methods of reforestry will be inaugurated by

the Canadian government the same as are in vogue in Norway and

Sweden. It is one of the greatest industries we have in Canada and

should be fostered so as to continue in perpetuity. |