|

Though the lumber

industry in the Provinces of Quebec and Ontario in the Dominion of

Canada is, so to speak, a double tree, growing from one root, it may

be well to consider them separately, passing lightly over that part

in each which more fully describes the other. The history of the

industry could not be otherwise than interwoven in these two

Provinces because from the beginning of things1

until 1791, whether under French or British rule, they constituted

one colony, and from 1841 to 1867 they were again united in the

Union of Upper and Lower Canada. In the latter year these two

Provinces, so different in language, religion, thought and habits,

were the basis of that confederation which bound all the scattered

colonies of Great Britain in North America (excepting Newfoundland)

into an independent auxiliary nation, with complete self-government,

with national responsibilities, and national aspirations; as Kipling

sings

Daughter am I in my

mother’s house,

But mistress am I in my own.

That confederation

would have been impossible but for the mutual forbearance—the

give-and-take—between these two great Provinces which now, after a

generation of expansion in greater Canada, still contain about

seven-tenths of the total population of the country, a forbearance

whereby the solid, Protestant, English-speaking Ontarian and the

dashing, Catholic, French-speaking Quebecer have, as in a marriage

contract, agreed to take each other for better or for worse, for all

time; and, having made up their minds to it, find each other not

such bad partners after all—in fact, preferable to any other of whom

they know.

Moving across the

stage of Canada’s history, crowded with commarrying figures, there

is none more picturesque than that of the lumberman beginning with

the cavalier seigniors of New France, continuing with the admiralty

officers of old England, with their retainers singing

French-Canadian boat songs, or fighting and praying as became good

Glengarry covenanters, on through the stirring times of the

rebellion of 1837 to the present time when, in the midst of a world

of timber dues and percentages, the successful lumberman still

builds his palace in the wilderness and becomes known as the King of

the Gatineau or the Prince of Petawawa.

Nothing comes out

more clearly in the early history of colonization in Canada than

that the tree was considered man’s enemy, and only valuable as a

barricade against other enemies, climatic or human.

The idea of those

who colonized New France was to reproduce the conditions of lord and

vassal, which they thought to be eternal but were only accidental

and were passing away in the old France even while they were vainly

striving to reproduce them in the new. By this system the land was

divided into large blocks, as large as a modem township, or small

county, and each block given to a scion of a noble house who

colonized his tract with tenants or retainers. These, in return for

occupancy of the land, not only paid rents but performed many

personal services, while the seignior on his part was invested with

many privileges ; among others, that of hunting over the retainer’s

land and of administering justice.

The place which

timber occupied in this system may be best seen by examining one of

the old seigniorial grants made in 1683 by the governor and

indendant of Quebec, which embodies the usual conditions. No excuse

is made in presenting it because it is a land grant, for from the

beginning to the present time land and timber regulations have gone

hand in hand:

We, in virtue of

the power intrusted to us by His Majesty [the King of France] and in

consideration of the different settlements which the said Sieur de

la Valliere and the Sieur de la Poterie, his father, have long since

made in this country, and in order to afford him the means of

augmenting them, have to the said Sieur de la Valliere given,

granted, and conceded the above described tract of land, to have and

to hold, the same himself, his heirs and assigns forever, under the

title of fief, seignory, high, middle and low justice and also the

right of hunting and fishing throughout the extent of the said tract

of land; subject to the condition of fealty and homage which the

said Sieur de la Valliere, his heirs and assigns shall be held to

perform at the Castle of St. Louis in Quebec, of which he shall hold

under the customary rights and dues agreeably to the Custom of

Paris; and also that he shall keep house and home and cause the same

to be kept by his tenants on the concessions which he may grant

them; that the said Sieur de la Valliere shall preserve and cause to

be preserved by his tenants, within the said tract of land the oak

timber fit for the building of vessels; and that he shall give

immediate notice to the King or to Us of the mines, ores and

minerals, if any be found therein; that he shall leave and cause to

be left all necessary roadways and passages; that he shall cause the

said land to be cleared and inhabited, and furnished with buildings

and cattle, within two years from this date, in default whereof the

present concession shall be null and void.

This extract shows

that the only interest the Crown took in the matter was the securing

of an ample supply of oak for building ships for the royal navy.

Later grants reserved timber for spars and masts, doubtless pine

timber. From time to time, as war vessels were built or repaired at

Quebec, permits were issued to parties to cut the oak timber

reserved as above and regulations were made for rafting it to

Quebec. Again, when new districts were opened in which oak timber

was reported to be abundant, regulations were issued forbidding

anyone cutting it until it had been examined and suitable trees had

been marked for the navy. The penalty for violation of this

regulation was confiscation of the timber and a fine of ten livres

for each tree.

These first

reservations caused trouble between the cultivator and his over-lord

or the Government, as similar arrangements have done ever since in

every part of the continent. If oak trees were numerous the tenant

had either to destroy them or fail to fulfill his obligations to

clear the land in a given time. The usual way of cutting the Gordian

knot appears to have been to bum the timber; but after suits by

seigniors against settlers who made the trees into boards for their

own use, it was ordained by the governor that the tenant should be

unmolested where the timber was cut .in the actual extension of his

clearing; but where the trees were cut for timber without the

intention of clearing the land the party should be fined.

When the land

became a little more cleared, trespass by settlers upon adjoining

lands to cut suitable sticks or easily reached timber became more

common and was punished by confiscation of the trucks and horses

used to transport the wood and by a fine of fifty livres. In the

district about Quebec City, one-half the fine and confiscation went

to the proprietor of the land and the other half to the Hotel Dieu

(hospital) of Quebec City.

At first the Crown

reservation of timber was solely for naval purposes, and timber

taken for military purposes, such as the building of casemates, was

paid for by the Crown; but later the reservation was extended to

include all timber the King might require. While the right of the

King was thus defined, the rights of the seignior were undetermined

and continued to be exercised conformably to Old World custom, with

more or less exactness, according to the strength of mind of the

seignior and the power of resistance of his retainers. These

seigniorial rights lasted long after British occupation and were

extinguished only by compensation, by the Seigniorial Tenures Act,

of 1854. The court which heard the claims decided that the seignior

had no right to timber for firewood for his own use, or to

merchantable timber or timber for churches; as to whether he had the

right to timber for manor house and mills, the court was divided. So

that in the closing years of the French regime the Crown reserved

the timber it required for its own use, and prohibited trespass,

while the seignior reserved what timber he could for himself by the

exercise of his will power over the tenant.

With the beginning

of British occupation, in 1763, the policy of reserving timber for

naval and military purposes inaugurated by the King of France was

continued by the King of England, and somewhat extended. The first

governor under the new regime, John Murray, was instructed to make

townships containing about 20,000 acres, and in each township he was

to reserve land for the erection of fortifications and barracks,

where necessary, and more particularly for the growth and production

of naval timber. He was further instructed to make reserves about

Lake Champlain and between that lake and the St. Lawrence, because

it had been represented to the King that the timber there was

suitable for masting and other purposes of the royal navy and

because it was conveniently situated for water carriage. He was to

prevent waste and punish any persons cutting the timber and to

report whether it would be advisable to prevent any sawmills being

erected in the colony without license from the governor or the

commander-in-chief. The modern school of forestry experts is

inclined to regret that these instructions as to reservations in

each township and permanent pine reserves on lands suited to pine

were not carried out, the reason being that other urgent matters

occupied the governor’s attention and subsequent exploration showed

the so-called illimitable extent of the pine forests.

In 1775 Guy

Carleton, captain general and governor in chief, received like

instructions, and in 1789 fuller regulations for the conduct of the

land office were made, preserving the timber to the Crown, confining

grants to individuals to lands suited to agriculture, and preventing

individuals from monopolizing such spots as contained mines,

minerals, fossils and water powers, or spots fit and useful for

ports and harbors and works of defense. These were to be reserved to

the Crown.

If these

regulations had only been carried out, how much would posterity have

been saved! The seignior, with his plumed hat, his ruffles, his

sword and turned-down top boots, as the sculptor represents him on

the public squares of Montreal, had disappeared and his place was

taken by a less artistic but more active individual, the royal

admiralty contractor. Licenses to cut timber were granted by the

British government to contractors for the royal dockyards, and

these, in addition to getting out timber to complete their own

contracts, took advantage of the opportunity to do a general

business in supplying the British markets. The timber was still

considered of such small value, above the cost of transport, that

these were apparently not felt to be serious abuses by the colonists

of that day.

EFFECT OF BRITISH

IMPORT DUTIES.

A new era dawned

for the Canadian timber industry with the close of the Napoleonic

wars. In 1787, by a consolidation of the duties on timber coming

into Britain, the rate was fixed at six shillings and eight pence

per “load” of fifty cubic feet upon foreign timber imported in

British ships, with an addition of two pence in case the shipment

was made in a foreign ship. With the increased taxation necessary to

carry on the wars to checkmate Napoleon’s ambitious schemes, the

duties rose steadily until, in 1813, they were £3 4s 6d a load, with

3s 2d additional when imported in a ship flying a foreign flag. The

decline in the duties began again in 1821 when they were fixed at £2

15s a load, with 2s 9d additional for importation in a foreign

vessel. Then for the first time a duty of 10s a load was imposed

upon colonial timber, which had been theretofore free. However, as

the colonies still enjoyed a preference of 45s a load, that did not

stop the progress the colonial timber trade was making. This was

shown by a report presented to a British parliamentary committee in

1833, to which was submitted the whole question of timber duties.

This report shows that the earlier duties levied were not

sufficiently large to overcome the prejudice which existed in favor

of Baltic timber. .

The first

noticeable change was in 1803, when the imports from British North

America reached 12,133 loads, compared with 5,143 loads the previous

year. How small was the colonial trade is shown by the fact that the

importations of European timber amounted to 280,550 loads. In 1807

the colonies supplied 26,651 loads as against 213,636 from Europe,

and in 1809, for the first time, the colonial product exceeded that

from Europe, the figures being 90,829, and 54,260 loads

respectively.

The War of 1812 had

a depressing effect upon colonial trade and Baltic timber again took

the lead until 1816, when the colonies supplied twice the quantity

sent by Europe. This was a period of expansion in Britain, so that

the total trade as well as that with Canada shows great growth. In

the five years from 1819 to 1823 the average annual import into

Great Britain was 452,158 loads, of which 166,600 came from Europe

and 335,556 from the colonies. The succeeding five years showed

still further growth to a total yearly average of 602,793 loads, of

which 410,903 came from the colonies, although in 1821 the duties on

foreign timber were reduced and a duty of ten shillings a load

imposed on colonial timber.

This is the first

place where we hear of the United States. In 1819 duties were

imposed by Canada upon goods coming from the United States, but

flour, oak, pine and fir timber for export were allowed to come in

free. The meaning of this was that a good deal of timber was brought

in from the United States and reshipped from Quebec to the British

market in order to obtain advantage of the preferential tariff in

favor of the colonies. The extent of this trade attracted the

attention of the British authorities, who had no intention that

United States producers should avail themselves of a preference

intended to help the colonies.

In 1820 an official

inquiry was instituted by the British House of Commons which showed

that the timber imported into Lower Canada from Lake Champlain from

1800 to 1820 included 10,997,580 feet of red and white pine,

3,935,443 feet of oak timber, 34,573,853 feet of pine plank and

9,213,827 feet of pine boards. As a result of this condition, by an

imperial act duties were imposed upon lumber brought in from the

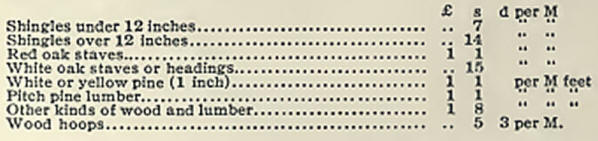

United States as follows:

This growth in the

use of the colonial product was made in the face of a very strong

prejudice in favor of the Baltic product. The select

committee of the

House of Lords which heard evidence on the subject in 1820 was

furnished with evidence on the part of timber experts as to the

inferiority of timber from British America which today not only

excites wonder and ridicule, but which demonstrates what an

important bearing sentiment has upon trade. One timber merchant and

builder examined by the committee said the timber of the Baltic in

general was of quality very superior to that imported from America,

which latter was inferior in quality, softer, not so durable, and

very liable to dry rot. Its use was not allowed by any professional

man under the Government, nor in the best buildings in London.

Speculators alone used it and that because the price was lower. Two

planks of American timber laid upon one another would show evidence

of dry rot in twelve months, while Christiania deals in like

situation for ten years would not show the like appearance. There

was something in American timber, he thought,, which favored dry rot

unless there was air on all sides.

In spite of this

prejudice2 the lower duty caused colonial

timber to be extensively used and once given a fair trial the

prejudice gradually disappeared. Fifteen years after the

investigation just recorded another was held by a House of Commons

committee, in 1835, which showed the change in opinion. One of the

witnesses here gave as a rea-'. son for the former prejudice against

colonial timber that while low-grades were brought in by “seeking”

ships, the high duty on Baltic timber kept all but the best grades

of that timber out, so that the British builder was acquainted with

the better grades only. A Liverpool ship owner and timber merchant

said that, if duties were equal, he could get from three pence to

four pence a foot more for a particular description of colonial

timber than he could for any Baltic. With this change of opinion

there had gone another, by which red pine, formerly preferred to

white, was dropped to second place, where it has ever since

remained. A Manchester builder declared that white pine in bricks

and mortar was less liable to decay than red pine or Baltic.

Canadian timber,

which thus got a foothold through a preferential tariff, continued

to hold its own in the years when the preference was gradually

reduced and finally abolished altogether in the adoption of free

trade. Nevertheless, while the trade grew, there is no doubt that

Canada felt the withdrawal of the preference not only upon lumber

but upon all her products severely, and it was this, more than

anything else, that caused the feeling of despondency and doubt

which preceded confederation, a depression from which it required

all the genius of Sir John Macdonald and the cooperation of his

associates to arouse the people with the vision of a self-contained

country stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific.

In 1850 the timber

exports from Canada (Quebec and Ontario) amounted to £971,375 and in

1857 the value had grown to £2,044,178. This had been accompanied by

a growth in exports to the United States. In 1867, the year when

confederation went into force, exports to Britain were $6,889,783

and to the United States $6,831,252.

CANADIAN

LEGISLATION AND LATER HISTORY.

In the preceding

pages has been recounted the effect of the laws of parliaments

outside of Canada upon the timber trade. Now it will be advisable to

consider the effect of the laws and regulations made in the country

itself.

The first enactment

of a Canadian legislature was passed in Lower Canada in 1805 to

prevent accidents in navigating the rapids of the St. Lawrence,

which, owing to the increasing shipments by that river to Montreal,

had become frequent. The act provided for the appointment of an

inspector and measurers of scows and rafts between Chateauguay and

Montreal and for the regulation of pilots. These officials, who were

to reside in the parish of Chateauguay, were from time to time to

take the depth of water of the rapids and determine what water scows

and rafts might draw in order to pass the rapids in safety. They

were, upon application, to measure the draft of each scow and raft

and to cause the former to be lightened to the draft determined as

the limit of safety. Pilots were to be licensed yearly by the

justices of the peace for Montreal, upon recommendation of the

inspector, for which license a fee of two shillings and sixpence was

charged. The pilots’ fees for taking rafts and scows through the

rapids were: Scows, 30 shillings; rafts consisting of two cribs, 12

shillings and 6 pence. Aftet October 1 to the end of navigation

these were increased by one-fifth.

Fines up to forty

shillings were imposed upon measurers or pilots neglecting their

duty and upon unlicensed persons acting as pilots. A pilot who,

without the consent of the owner, left a raft or scow stranded in

the rapids was fined the loss of his fees and 20 shillings. The

pilot was allowed 5 shillings a day while he remained with the wreck

and assisted in saving the property and in clearing the rapids of

the obstruction. The fees for measurements were : Scows, 6 shillings

; crib and rafts 2 shillings and 6 pence, and rafts of firewood 1

shilling 6 pence. These fees, by an act of 1808, were applied to the

improvement of the rapids.

In the same year an

even more important measure affecting the industry was passed. This

provided that no lumber should be exported until it had been culled,

measured and certified as to quality. The governor was authorized to

appoint master cullers at Quebec and Montreal who were to ascertain

the quality and dimensions of the articles submitted to them and to

give a true and faithful account of those found merchantable, which

was to be final and conclusive between buyer and seller. The act

laid down the standards for square oak and pine, planks, board, etc.

It was reenacted in 1811 and 1819 and made more stringent in its

provisions. At the same time in all these acts there were most

contradictory clauses. In some the shipment of unstamped timber (as

having passed the culler) was prohibited, while in others it was

stated that second or inferior grade lumber might be exported. The

cullers were apparently governed by the contract between the buyer

and seller, and the rigid definitions of what constituted

merchantable timber were only to apply where no specific agreement

between the parties existed. After being put beyond question upon a

voluntary basis in 1829, it was finally allowed to expire by lapse

of time, in 1834.

There was no

further legislation on this point until after Quebec and Ontario

were united in 1841 (Ontario having been created a separate

province, called Upper Canada, in 1791). In 1842 an act was passed,

further amended by an act of 1845, which got over the previous

difficulties by creating three grades for timber and deals.

As in Ontario, the

Crown first began to collect timber dues in 1826, and the

regulations in this respect followed those of Ontario until the

union of the two Provinces. As a rule, however, Ontario, by reason

of greater facility in getting lumber to market, has charged dues a

little higher than her sister province. As in Ontario, from the

first the Crown adopted the plan of not selling timber lands but of

granting a license to cut timber upon Crown lands within a certain

specified time, at the end of which the land returned to the Crown

either to be granted to the settler for agricultural purposes or to

be held until the timber grew again. The way in which these wise

provisions were evaded for many years was this:

Since the timber

cost money and the land was free or sold at a very low price on easy

terms to the settler, men who never intended to farm the land, or to

settle farmers upon it, got areas large or small granted to them

and, having stripped them of their timber, allowed them to go back

into the hands of the Government. Where they had made a small first

payment they either let that go as a fine or endeavored to sell out

to a bona fide settler.

Quebec, or Lower

Canada, passed through the same period of wasteful granting away of

Crown lands as did Upper Canada, and this period culminated in a

like rebellion in 1837 and the granting of responsible government,

when the two Provinces were united in 1841. The two Provinces then

for over a quarter of a century, until 1867, enjoyed laws common in

nearly every respect. The timber question was one of the first taken

up and the regulations made at the first session of the united

parliament laid the foundation of all subsequent progress in

forestry.

The orders in

council of 1842 limited the period for which the license was

granted, and introduced the plan of putting the berths up at auction

where there was more than one applicant. The rule had been that the

applicant simply paid the dues; and there had been much Crown land

covered with timber in regard to which lumbermen did not clash or

compete. Now, however, the easily reached limits began to grow

scarcer and the applicant who offered the highest “bonus” or lump

sum for the limit, in addition to the dues, was awarded it. In all

these cases the timber only was sold, the land being reserved on the

general principle that it would be taken up by the settler after the

timber was taken off. The ignoring of the fact that much of the land

was not fit for settlement was the chief fault in these regulations,

because the idea of the time limit seems to have been handled

chiefly in such a way as to insure that the operator would at once

proceed to work his limit. The consequence has been that where the

land is not fit for settlement some firms that got their licenses in

the early days have continued holding and cutting over limits for

many years, whereas, had the lease terminated absolutely on a

certain date, the berths would have gone back into the hands of the

Government, which, after allowing them to rest for a few years,

might have resold them for a greatly increased bonus. As it is the

Government secures only the ground rent of about $3 a mile per annum

and the dues on the timber cut. Later regulations have been more

definite and the worked limits are now year by year falling back

into the possession of the Crown.

Further regulations

made in 1846 restricted the size of the limits to five miles

frontage along the stream and five miles inland, or half way to the

next river. The licensee bound himself to cut 1,000 feet a mile

yearly on his limit.

The season of 1845

was a prosperous one in the trade, and 27,702,000 feet were brought

to Quebec and 24,223,000 feet exported. This good trade caused an

over-production in the next year, and as the British trade fell off

there was a serious depression. This was accentuated by the

provision that the operators must cut 1,000 feet a mile each season

on their limits regardless of the conditions of the trade.

The inevitable

parliamentary committee of inquiry appeared in 1848, before which W.

W. Dawson, a leading By town (Ottawa City) lumberman, stated that in

1847, including the quantity in stock and that brought to market,

there was a total supply of 44,927,000 feet to meet a demand for

19,060,000 feet. The next year the supply was 39,447,000 feet and

the demand 17,402,000 feet. He attributed the decreased demand to

the commercial depression in Europe and the unprecedentedly large

supply thrown upon the European market from the Province of New

Brunswick. As to the over-supply he gave three reasons: The

regulations requiring the manufacturing of a large quantity per

mile; the threatened subdivision of limits, and the difficulties

regarding boundaries.

The threatened

reduction or subdivision of limits in three years to the size of

five by five miles caused operators to endeavor to clear off their

big limits before being compelled to hand them back to the

Government. The lumbermen accused the Government of inaction in

regard to their boundaries, and in consequence, in order to defend

their limits, they had resort to physical force. This meant that the

operator trebled or quadrupled his men to be superior in numbers to

his opponent, and, as the men were on the ground, this meant the

trebling or quadrupling of the output.

The chief remedy

suggested by the lumbermen to the committee was that, instead of

endeavoring to prevent the holding of limits for speculation by

compelling the cutting of a certain amount of timber a year, an

annual ground rent of two shillings six pence a square mile should

be levied, which should be doubled in case of nonoccupation, and the

doubling continued every year the limit remained unoccupied. They

also suggested that the dues be collected upon actual measurement

instead of upon a count of sticks. For instance, red pine was

figured on an arbitrary average of thirty-eight feet a stick,

whereas the sticks ran from twenty-six to sixty feet, and a spar or

mast worth £10 paid only the same duty as a small stick available

for building.

The committee

reported recommending such action, and as a result the"first Crown

timber act was passed in 1849. This cleared up many points in

dispute. Under the regulations accompanying the act the size of

berths permitted was doubled; that is, ten miles along the river by

five miles deep, or fifty square miles, but only half that size was

permitted in surveyed townships. The dues imposed were : White pine,

square timber, }4d a foot; red pine, square timber, Id; basswood and

cedar, J4d; oak, l%d; elm, birch and ash, Id; cordwood, hard, 8d a

cord; soft, 4d; red pine logs, twelve feet long, 7d a log; white

pine logs twelve feet long, 5d; spruce, 2}4d. Each stick was to be

computed as containing cubic feet as follows: White pine, 70 cubic

feet; red pine, 38; oak, elm, ash, birch, cedar and basswood, 34.

Statements under oath were to be made of the kinds and quantities of

timber cut. The ground rent plan was not adopted, but the minimum

quantity to be cut on each mile was reduced to 500 feet a year.

There was one

clause which gave rise to a great deal of trouble in after years.

This provided that squatters were liable to the penalties for

cutting timber without license, but the dues on timber cut on land

purchased but not all paid for were to be collected by the

Government as part payment for the land. The arbitrary regulation as

to the quantity in each stick was made elastic by providing that the

operator could have the timber counted or measured as he chose. The

regulations also gave the limit holder a preferential claim above

all others to a renewal of his license, and thus gave greater

permanence to the lumbering business. .

In the regulations

of 1851 a ground rent of two shillings six pence a mile was

introduced, which rent doubled and increased annually in that

proportion, when the limit was not worked. It was provided also

that, where expenses of surveys made it advisable, licenses might be

disposed of at an upset price fixed by the Commissioner of Crown

Lands; and, in case of competition, awarded to the highest bidder.

Owing to the representations of mill owners and municipalities in

western Ontario, chiefly about London, the dues were doubled when

the logs were destined for export. This was to protect manufacturers

against the practice by American citizens of procuring lands at a

low rate for the purpose of cutting timber to be manufactured in the

United States.

The good effect of

these new regulations was at once seen. The revenue had been £22,270

in 1848; £24,198 in 1849; £24,728 in 1850 and £30,318 in 1851. In

1852, the first year the new regulations went into force, the

receipts rose to £53,013, of which £7,656 was for ground rent, and

this in spite of the fact that dues on red pine had been cut in two.

Up to this time red pine bore a penny a foot, while white pine bore

only a half-penny; but, owing to the decline in the British

preference for red pine, it had gone down in price and white pine

had gone up. This seems to have been a case where prejudice backed

by higher import duty gave red pine a fictitious value for years. A

memorial of manufacturers showed that the price of red pine

decreased from one shilling in 1844 to eight pence in 1851. The duty

was accordingly reduced to one-half pence a foot. The ups and downs

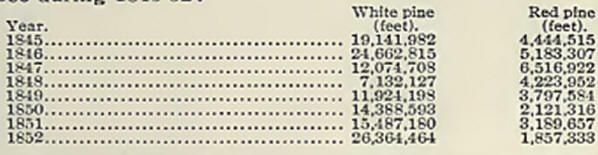

of the trade are shown in the returns of timber measured by the

supervisor of cullers at Quebec during 1845-52:

From 1841 to 1867

Quebec and Ontario constituted one province, and the regulations,

with some exceptions to meet local needs, were the same in both

sections. These are set out at considerable length in the chapters

on Ontario and need not be repeated here. In general it may be said

that the plan of selling the rights to cut timber under license,

allowing the land to remain in the possession of the Crown was

developed, the bonuses paid at the auctions held growing larger and

the dues and ground rent heavier as the timber increased in value.

The original export

trade of Canada in timber looked wholly to Europe as its market, and

of this trade Quebec City was the center. This trade appears to have

reached its zenith about 1864 when 1,350 square rigged ships entered

the St. Lawrence to load lumber, and when 20,032,520 cubic feet of

white pine timber was shipped. The wastefulness of the square timber

trade, the decline of wooden ship building and the rise of the new

export trade with the United States all operated against Quebec’s

preeminence, and the trade declined, much of it going to Montreal.

Of late years, however, new railways, the bringing in of spruce as a

valuable wood, and above all the ambition and energy of the citizens

of the old capital of Canada, have set it on the up grade again.

Since 1867, when Quebec became a province in the Dominion and

separated from Ontario, the provincial revenue derived from the

forests has steadily increased, with slight fluctuations showing the

effects of world-wide depression or prosperity.

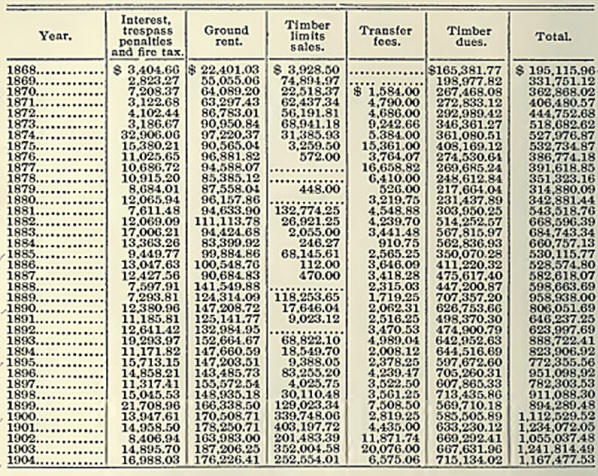

The following

table, by fiscal years ending June 30 of each year named, shows the

amounts collected from Crown lands, as timber dues,, ground rent,

timber limits sales, etc.:

As to the

quantities of timber cut in Quebec, this is not easy to ascertain,

since different methods have been adopted at different times and the

products of private lands are not included, except in the decennial

census. This is particularly the case with pulpwood, which has

become an article of great importance in the last few years. The

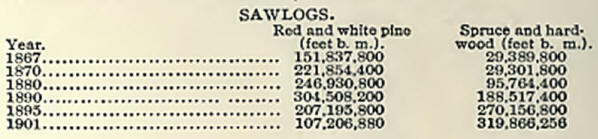

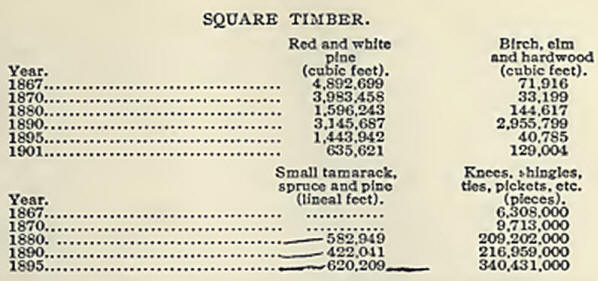

following tables are of timber cut on Crown lands:

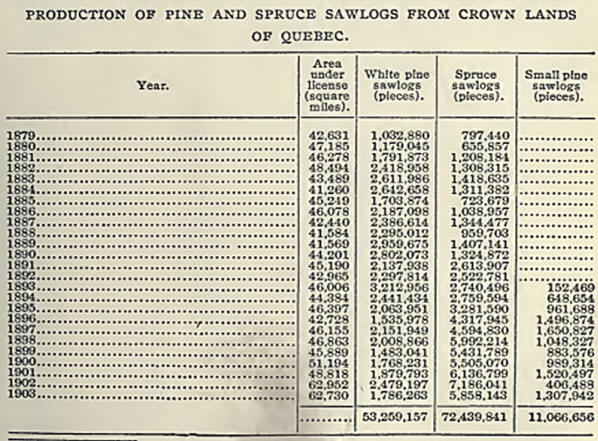

A review of the

area of Crown lands in Quebec under license to cut timber and the

quantity of sawlogs produced from such lands is interesting as

showing the changes in areas so held, the gradual decline in the

pine trade, due to the diminishing supply of pine timber, and the

rapid growth in recent years of the spruce industry. Such a table,

covering the twenty-five years ended with 1903, has been compiled3

from the reports of the Commissioner of Crown Lands. It is as

follows:

It is only within

the last few years that pulpwood has become of consequence, but in

1903 the Government reported a total of 259,231 cords cut on Crown

lands. There were also in that year 94,079 lineal feet of poles,

780,960 railway ties, 9,174 pickets, 2,424,500 shingles, 426 rails,

23 T/t cords of hemlock bark and 11,710 cords of white birch spool

wood.

The most important

point at the present time is the outlook for the future. It may be

said that, whereas ten years ago very pessimistic views were

entertained as to the quantity of timber left standing in Quebec,

today the views are much more hopeful. There are two reasons for

this: First, the development of the use of other woods, particularly

of spruce; and, second, the realization that if fjre is kept out and

the fake settlers stopped, the forests will reproduce themselves

much more rapidly than formerly supposed. Besides, people are realiz-,

ing that much of Quebec is unsuited for agriculture, whereas these

districts are eminently suited for the perpetual growth of timber.

The Government and the lumbermen are cooperating in the preservation

of the forests by a system of fire ranging and by leaving the young

timber to attain its full growth. Senator Edwards, of Ottawa and

Rockland, one of the largest limit holders in Quebec, in speaking

recently on this subject said that his candid opinion was that

Quebec possesses today the best asset in America. Ontario has timber

larger and of better quality, but Quebec has the young and growing

timber. The pine in sight, Mr. Edwards was inclined to think, might

last, with care, fifty years, but if fires (which have destroyed ten

times as much as the ax) are kept out and settlement prohibited on

the small areas of go6d land occurring in the forest regions, the

trade might be continued indefinitely.

As Quebec is the

largest eastern province and also the greatest forested province in

the Dominion, with a land area of 341,756 square miles, and reaches

back into the unexplored north, it is likely that it will continue

to be the great source of timber production in Canada.

During the spring

of 1904 a commission reported to the Quebec government against

indiscriminate settlement, with the result that the Government and

the lumbermen are nearer together and working more in harmony than

ever before. The commission favored an increase in the numbers and

joint control of the fire rangers; and, seeing that a million

dollars a year of the provincial revenue comes out of forests, the

legislators can be relied upon to be anxious to preserve the goose

which lays this golden egg.

Both Quebec and

Ontario have been fortunate in the supply of right kind of labor for

this trade. The cheerful, fun-loving, hardy French-Canadian takes to

lumbering like a duck to water. His skill in handling the ax, in

driving, in walking on floating logs and in jam-breaking, have a

world wide celebrity; while the songs with which he lightens his

labors with the oar or on snowshoes are a national inheritance and

pride. Curiously enough from the other side of the great river, from

the Ontario shore, have gone with him the men of a supposedly

antithetical race, the canny, dour Scots of Glengarry County, men

who knew no language but Gallic and no law but the strong hand.

Although they have fought for their masters over disputed lines and

fought for themselves out of sheer prowess so as to make “ The Man

from Glengarry ” one of the most picturesque of modem novels, yet

these deeds of daring have served only to unite the two sides of the

Ottawa in firmer bonds of respect and admiration. |