|

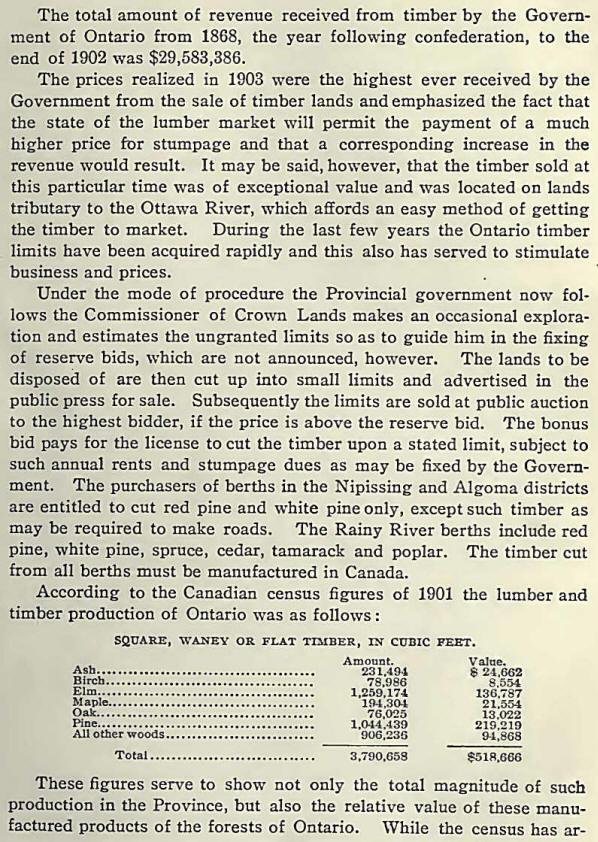

In 1871 there was

an extensive sale of limits in Muskoka and Parry Sound districts,

fronting on Georgian Bay. The dues at this sale were double those of

the previous one, white pine and red pine being two and one-half

cents a foot, or thirty cents a standard. The area disposed of was

487 miles, and the price was $117,672. A still more extensive sale

was the one which took place in 1872, when 5,301 miles on the north

shore pf Lake Huron was disposed of for $602,665. More than

three-fifths of this area had previously been under license, but,

with the exception of thirty square miles, all had been allowed to

lapse.

Legislation was

enacted gradually settling the settlers’ rights and then came the

great river and stream bill suit. This occurred in 1881, when the

Ontario government passed an act permitting lumbermen on the upper

reaches of streams to use slides and other improvements lower down

upon the payment of reasonable dues. Peter MacLaren, the great

Ottawa lumberman, who had made improvements on the Mississippi River

in Lanark County, claimed the right to prohibit the lumber of the

limit holders above him passing through his improvements. The

Dominion government took the side of Mr. MacLaren and disallowed the

Ontario act, but the case was finally determined in favor of

Ontario, and since then lumbermen have had full right to use

improvements upon paying tolls fixed by law.

In 1887 standing

timber had so increased in value that the dues on sawlogs were

increased to $1 a thousand and upon square timber to two cents a

foot. The ground rent was increased from $2 to $3 a mile. Under

these regulations extensive sales were made on the Muskoka and

Petawawa rivers. A new principle was introduced in 1892 when the

lumbermen were restricted to the cutting of red pine and white pine,

leaving spruce, cedar, hemlock, basswood and other woods to be

disposed of otherwise by the Government. It was under these

regulations that extensive sales were made in the districts of

Nipissing, Algoma, Thunder Bay and Rainy River. The dues were

increased to $1.25 a thousand feet on sawlogs and $25 a thousand

cubic feet on square timbers. Notwithstanding this, higher prices

were realized than ever before. The mileage sold was 633, for which

$2,315,000 was realized, an average of $3,657.18 a square mile.

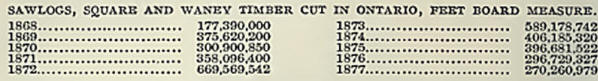

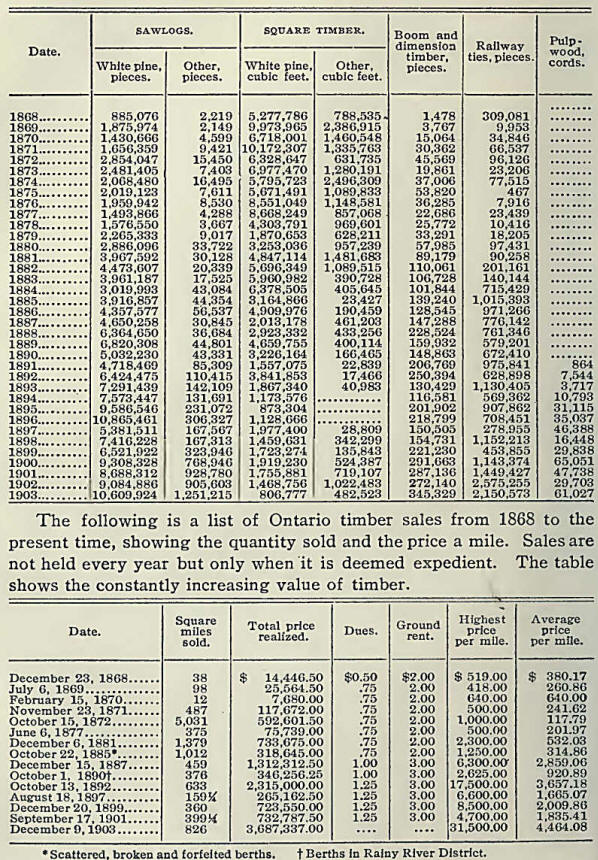

The fluctuating

state of the trade was shown in a return made to the Ontario

Legislature in 1878 of the sawlogs, square and waney timber cut each

year from 1868 to 1877:

The Commissioner of

Crown Lands figured that the waste of material in the shipping of

square timber instead of sawlogs in the above meant a loss of

revenue of. $3,577,500, or $357,750 a year, and he urged changing

over from square timber to sawlogs.

While for many

years the cry has been heard that Ontario is at the end of her

timber resources, this is not the view taken by certain well

informed men. The late John Bertram, of Toronto, who was one of the

best informed practical lumbermen and foresters in Canada, stated in

an article published shortly before his death that, while there was

a much increased demand for home consumption both in Ontario and in

the prairie country in western Canada, he did not look for an

increase in the quantity sawed in Ontario or Quebec because, “ while

there is a large quantity of pine and spruce still available, the

forests are beginning to show signs of exhaustion, and it is a

fortunate circumstance that many lumbermen are showing interest in

the question of reafforestation. The Ontario government has shown

wisdom in its system of fire ranging and in setting apart forest

reserves in the territory not fit for cultivation. This will prolong

the business indefinitely.” The most noteworthy feature of the

lumber industry of recent years has been its rapid development in

the northwestern portion of the Province. This has been stimulated

by the growing demand for the output in Winnipeg and other parts of

Manitoba, which look to the mills of Rat Portage, Rainy River, Fort

Frances and other centers in the Rainy River district as their

nearest source of supply. The continued migration to the West and

the growth of Winnipeg have given a remarkable stimulus to the

production of lumber in . this portion of Ontario.

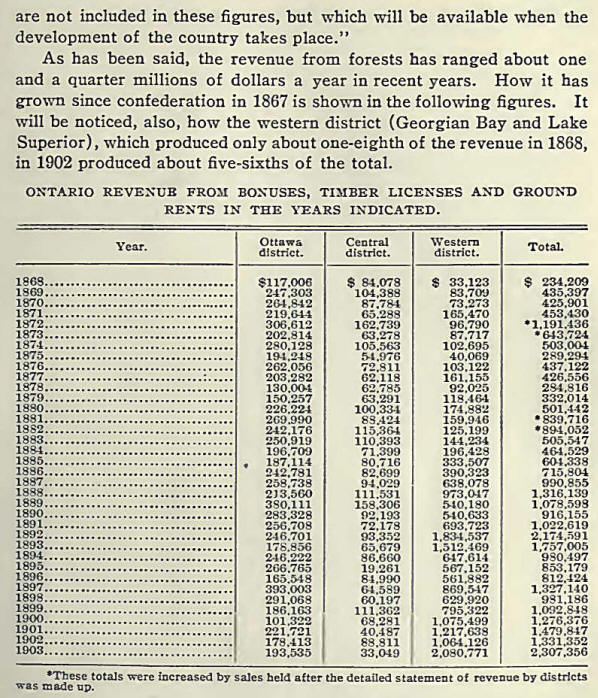

The income derived

from timber forms a considerable portion of the revenue of the

Province which, owing mainly to the large receipts from this source,

is in the fortunate position of being entirely free from debt and

able to meet all the expenses of administration, in addition to

spending a great deal of money in public services, such as elsewhere

are sustained wholly by the municipalities, without resorting to

direct taxation. In 1903 the total revenue collected from timber was

$2,307,356, the amount being exceptionally large, however, owing to

the holding of an extensive timber sale, at which high prices were

realized.

The increase in the

value of this source of national wealth of late years was indicated

by the result of this sale, at which about eight hundred and

twenty-six square miles was disposed of. Notwithstanding that the

timber dues were raised to $2 a thousand feet board measure on logs,

and to $50 a thousand cubic feet on square timber, and the ground

rent increased from $3 to $5 a square mile, the amount realized as

bonuses was $3,687,337, or an average of $4,464 a mile. The highest

price paid per mile was $31,500. The new record this sale

established as to the great and increasing value of the pine-bearing

lands of Ontario has contributed much to educate public opinion as

to the need of forest preservation and to strengthen the hands of

the Government in its policy in that regard.

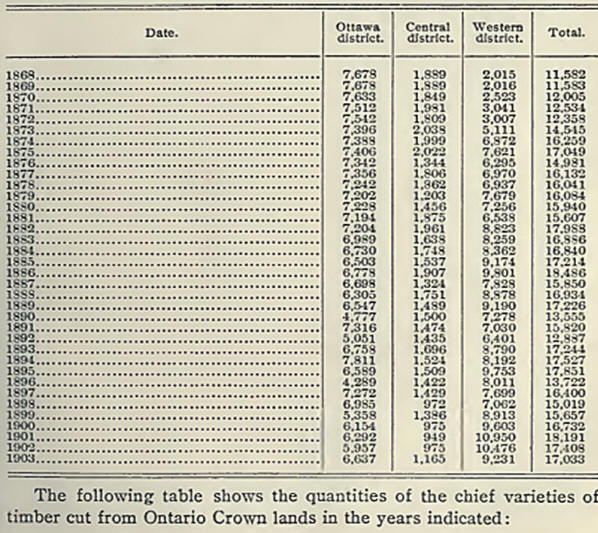

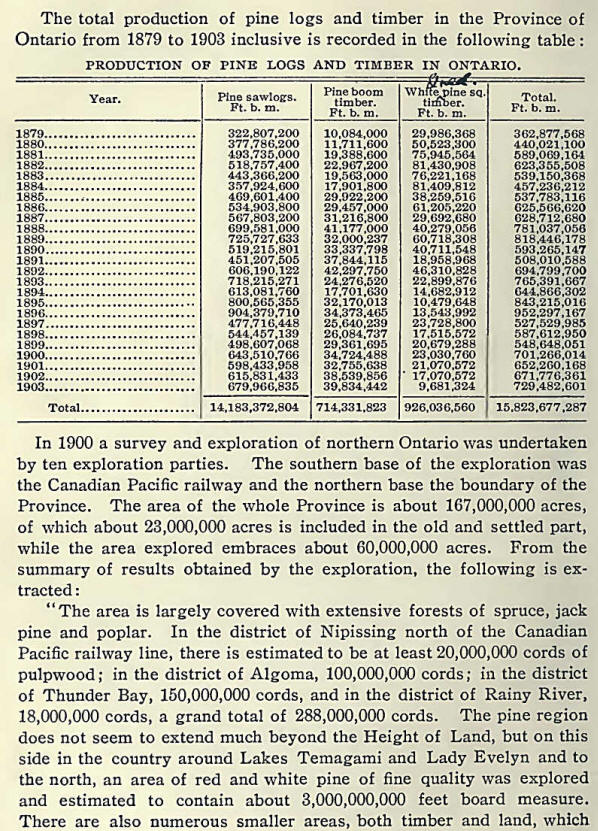

The total area now

covered by timber licenses in Ontario is 17,033 square miles, of

which 9,231 are in the western timber district and 6,637 in the

Ottawa district. The total production of sawlogs in 1903 was

679,966,835 feet board measure, of which 549,488,617 came from the

western district as against 104,576,242 from the Ottawa district. In

pine boom and dimension timber the total output was 39,834,442 feet,

the West leading in about the same proportion.

As the entire

forest area of the Province is estimated at 102,000 square miles,1

it will be seen that the territory now under license forms but a

comparatively small proportion of the timber resources yet

available.

It is customary in

taking stock of the available assets in the way of pine timber, to

ignore the territory already disposed of and under license, but some

of this territory has been under license for over forty years, is

still being operated and is contributing yearly to the provincial

treasury, and, so long as this territory escapes the havoc of forest

fires and is free from the settler’s plow, so long will it continue

a source of public revenue.

As to the available

white pine supply in the Province outside the present licensed area,

no attempt at a careful estimate has yet been made. E. J. Davis,

Commissioner of Crown Lands for Ontario, speaking in the legislature

February 18, 1904, gave an estimate prepared by his department. In

this he estimated the amount of white pine still standing in Ontario

at 10,000,000,000 feet, which would suffice for twenty sales such as

that of December 9, 1903, when limits were sold for about $3,500,000

in bonuses. This 10,000,000,000 feet should realize, he said, in

bonuses $75,000,000. The dues had been increased previous to the

last sale from $1.25 to $2 a thousand feet, and the dues on this

pine would produce at least $20,000,000. The surveys of the north

country had shown that there were at least 300,000,000 cords of

pulpwood standing, which, with dues of twenty-five cents a cord (the

present dues are forty cents) would produce $75,000,000 for the

provincial treasury. There was in sight at least $200,000,000 of

revenue, which at $2,000,000 a year would last the Province for one

hundred years. The average revenue in recent years from the forests,

he pointed out, was between $1,250,000 and $1,500,000 a year, of

which $800,000 was dues. This was assuming that the forest was all

used up as time went along; but he then explained what the Province

was doing to keep up a perpetual supply. Passing over the small

timber preserves where the Government, to allow the timber to grow

again, has taken back into possession lands cut over or partly cut

over under licenses, he described the reserves made in the virgin

forest which had been rendered accessible by the building of the new

government railway from North Bay to Lake Temagami and northward.

The original Temagami Reserve around the lake of that name consisted

of 2,200 square miles. This had been increased to 5,900 square miles

and, when he spoke, it had just been decided to set apart 3,000

square miles in Algoma district to be known as the Mississaga

Reserve. The old plan of license by which the lumbermen handed back

the land to the Government when they had cut off the timber was

probably the best that could be devised where the land was arable,

for the Government could then grant it or sell it to the settlers;

but in these reserves where the land is unsuited to agriculture

another plan would have to be devised, which would probably take the

form of a government forester marking the trees to be cut, which

would then be sold by auction, the lumbermen agreeing to cut and

carry away the timber in such a way as to reduce fire risk and give

undeveloped trees a chance to grow. From the cutting of continually

recurring crops of ripe timber on these reserves he anticipated a

revenue of several million dollars a year to the treasury, and

further reserves are to be made from time to time.

In a speech

delivered March 12, 1901, in the Ontario Legislature, Hon. William

A. Charlton (who has since assumed office as commissioner of public

works) stated that the average yearly cut, including logs, boom and

square timber, from 1867 until that date amounted to 549,141,408

feet. The largest cut of any one year was that of 1896, amounting to

952,000,000 feet. He estimated the total quantity of pine timber on

lands then under license at 8,000,000,000 feet, and the quantity not

under license at that time at 26,000,000,000, making in all

34,000,000,000 feet of pine timber then standing. He considered

that, without reference to regrowth or reforestry, the supply was

sufficient to last one hundred and fifty years.

The story of the

westward movement of the trade is told in the report of square miles

under license, although it is to be remarked that an immense area in

the Ottawa district remains under license, showing that much of this

district will permanently remain under timber.

|