|

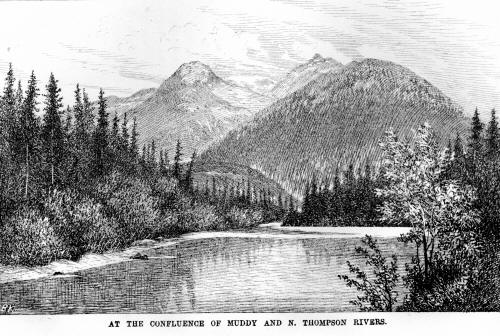

Breakfast by Moonlight.—The

Bell-horse.—Mount Cheadle.—Blue River and Mountains. —Goose Creek—The

Headless Indian.—Porcupine Breakfast.—The Canyon.—Mule Train.—AtHell Gate,

meet friends.—Gathering at Camps U. and V.—Good cheer-— Still water.—Round

Prairie.—Exciting news two months old.—Change in the Flora. —Bunch

Grass.—Raft River.—Clearwater.—Boat to Kamloops—Assineboine Bluff. —Last

night under canvass.—Siwash Houses.—Signs of Civilization.—Stock

Raising-—Wages in British Columbia.—Arid aspect of country.—Darkness on

the river.— Arrival at Kamloops.

September 23rd.—Jack rose

this morning at 3 A.M., and made up the fire by kicking the embers

together and piling on more wood. In a quarter of an hour after, all hands

were up— folding blankets, and packing. We breakfasted by moonlight, and

would have been off by five, but two of the horses had wandered and it was

some time before they were found. Jack tracked them to an island in the

river and had to wade across for them. Notwithstanding the delay we left

camp at 5.45 A.M.

This was the first occasion

on which any of the horses had strayed even a short distance away from the

bell. They had always kept within sound of it on the journey and during

the night. The bell is hung round the neck of the most willing horse of

the pack, and from that moment he takes the lead. Till he moves on, it is

almost impossible to force any of the others forward. If you keep back

your horse for a mile or two when on the march, and then give him the

rein, he dashes on in frantic eagerness to catch up to the rest. Get hold

of the bell-horse when you want to start in the morning, and ring the bell

and soon all the others in the pack gather round.

We had never seen the

gregariousness of horses so strongly exhibited as in the case of those

Pacific pack-trains. And the mule shows the sentiment or instinct still

more strongly. A bell-horse is put at the head of the mule train, and the

mules follow him and pay him the most devoted loyalty. If a strange dog

comes up barking, or any other hostile looking brute, the mules often rush

furiously at the enemy, and trample him under foot, to shield their

sovereign from danger or even from insult. Altogether the bell-horse was a

novelty to us, though his uses are so thoroughly understood here, that

Jack and Joe were astonished at our asking any questions about so well

established an institution.

The night had been frosty,

and the ground in the morning was quite hard, but after we had been on the

road for an hour, the sun rose from behind Mount Cheadle, and warmed the

air somewhat, though it continued cold enough all day to make walking

preferable to riding. For the first four miles the road was similar to

Saturday's. We then came to a mountain stream, towards the mouth of which

the view opened and showed us Mount Cheadle rising stately and beautiful

from the opposite bank of the Thompson. What had seemed yesterday a great

shoulder stretching to the south was now seen to be a distinct hill, but

in addition to the cone or pyramid with the twin heads of Mount Cheadle, a

third and lower peak to the north east now appeared. Beyond the stream is

Cranberry marsh. The trail here goes along the beach for a short distance,

and then turns into the woods and hills again, giving us a repetition of

Saturday's experiences. Eight miles from camp we crossed another and

larger stream on the other side of which the valley widened and the

country beyond opened. The landscape was softer and the wild myrtle and

the garden waxberry mixed with the ruder plants that had held entire

possession of the ground farther up. Eight miles more brought us to open

meadows along the banks of the river, overgrown in part by willows and

alders, and in part covered with marsh grass. Here a halt of two hours for

dinner was called. We had travelled about sixteen miles in five hours, and

had only ten more to travel, to reach Goose Creek, where camp was to be

pitched for the night. It was expedient to get there as early as possible,

that the horses might have a good feed, for there would be no grass along

tomorrow's road, which was also said to be the worst between Yellow Head

Pass and Kamloops.

During the last two or

three days the river had fallen very much, and at our halting place it was

eight or nine feet below its high water mark. The valley was wide enough

to enable us for the first time to see on both sides the summits of the

mountains that enclosed it. At this point they are remarkably varied. A

broad deep cleft in the heavily timbered hills on the west side of the

river, showed an undulating line of snowy peaks, rising either from or

behind the wooded range; and the opposite side was closed in nearer the

river, by a number of separate mountains, probably from four to six

thousand feet high, that folded in upon or rose behind one another.

The afternoon drive was

along a level, for the next six or seven miles to Blue River, where our

progress was slow from the stubs or short sharp stumps of the alders, that

dotted and sometimes completely filled up the trail. Blue River gets its

name from the deep soft blue of the distant hills, which are seen from its

mouth well up into the gap through which it runs. A raft is kept on this

river for the use of the survey. We made use of the Cache or shanty on the

bank, opening it for a small supply of beans and of soap. A diligent

search was made for coffee but without result.

The timber here is small

and much of it has been destroyed by fires. After crossing the river, the

trail winds round a bluff that extends boldly to the Thompson. Timber that

had fallen down the steep face across the trail delayed us several times.

Frank shot a large porcupine as it was climbing a tree, and pitched it on

the kitchen pack to be tried as food. Three miles more brought us to Goose

Creek where we camped an hour before sunset. This was the spot the Doctor

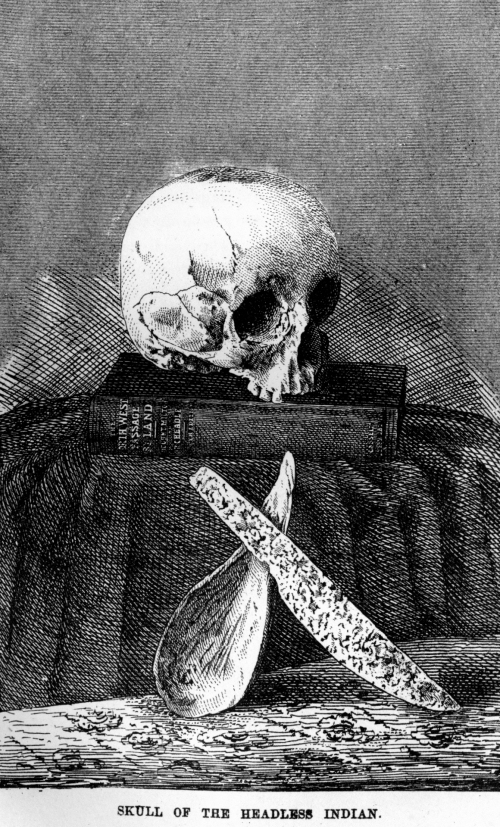

had been told to examine for the bones of " the headless Indian," and

therefore as soon as he had unsaddled his horse, he selected a shingle

shaped stick and, without saying a word, set off on his exploration with

all the mystery and deliberation of a resurrectionist In a few minutes he

came on a bit of board with the following inscription pencilled on it:—

"Here lie the remains of

the "Headless Indian," discovered by Lord

"Milton and Dr. Cheadle, A. D. 1863. At this spot we found an old

"tin kettle, a knife, a spoon, and fishing line; and 150 yards up the bank

"of the river we also found the skull, which was sought for in vain by

"the above gentlemen.

"T. Party, C. P. R. S.

"June 5th, 1872."

Scratching the ground with

his wooden spade the Dr. was soon in possession of the skull and of the

rusty scalping knife, that had been thrown in beside it, and finding the

old kettle near, he appropriated it too, and deposited all three with his

baggage, as triumphantly as if he had rifled an Egyptian tomb. Terry did

not like the proceedings at all, and could only be reconciled to them on

the plea that they might lead to the discovery of the murderers; for

nothing would persuade him that the man's head had dropped off, and been

carried to a distance by the wind or some beast. He had seen heads broken,

or cut off, but he had never heard before—and neither had we as far as

that goes—of a head rolling off; and therefore concluded that "there had

been some bad work here."

Frank and Jack skinned the

porcupine, and prepared it for cooking ; and Jack boiled some beans to be

eaten with it. A leg being spitted and broiled before the fire as a test

morsel, was pronounced superior to beaver; and the carcase was consigned

to Terry, who decided to cut it up, parboil, and then fry it for

breakfast. September

24th.—There was no need to look at the thermometer when we got up, to know

that there had been frost. Every one felt it through the capote and pair

of blankets in which he was wrapped. The Chief rose at midnight and

renewed the fire. Frank then got up and curled himself into a ball within

a few inches of the red embers. At 3 A.M., all rose growling, stamping

their cold feet, lingering about the fire, lighting pipes, and considering

whether washing the face wasn't a superstitious rule to be occasionally

honoured in the breach rather than the observance. Everything was done

slowly. It was nearly sunrise before any one even thought of looking at

the thermometer, which then indicated 17°: not so very low, but we had

been sleeping practically in the open air, and in a cold wind with rather

light covering. Three-quarters of an hour were spent in cooking the

porcupine ; and as it did not come up to our expectations, from inherent

defects or Terry's cooking, very little of the meat was eaten; and no one

proposing to carry a piece in his pocket for lunch, it was left

behind,—the only thing in the shape of food that had ever been wasted by

us on the journey. At

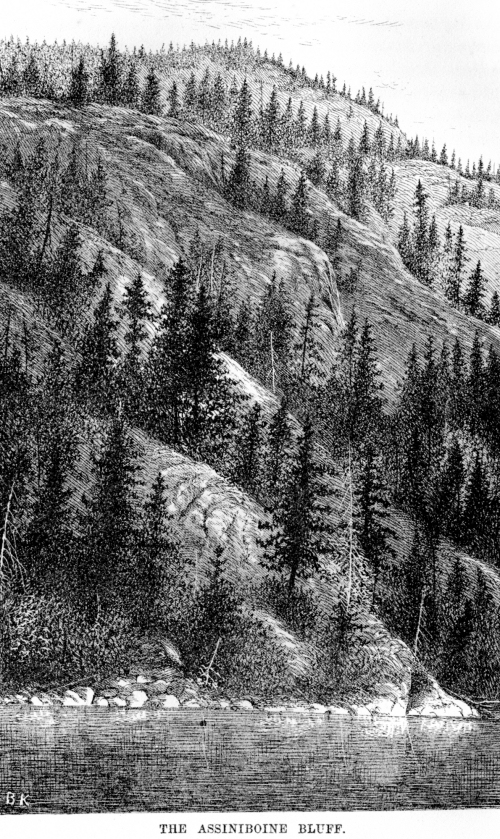

6.15 AM. we were on the march, expecting a heavy day's work, as the road

lay over the Great Canyon that had all but defeated Milton and Cheadle's

utmost efforts, and past the 'porte d' enfer' of the Assineboine. The

first three miles after crossing the Creek were partly round and partly

over a heavy bluff; and the next five along the river, which ran like a

mill-race between high hills. These hills on our side afforded space for

the road either along their bases, or on the first bench above. The next

ten or twelve miles were to be through the dreaded canyon; a pass as much

more formidable than Killiecrankie as the Thompson is greater than the

Garry. While climbing the first bluff near the entrance to the canyon, the

bell-horse of a pack-train was heard ahead. Fortunately there was space

for us to draw aside and let the train pass. It was on its way up to Tete

Jaune Cache with supplies, and consisted of fifty-two mules led by a

bell-horse, and driven by four or five men, representing as many different

nationalities. Most of the mules were, with the exception of the long

ears, wonderfully graceful creatures; and though laden with an average

weight of three hundred pounds, stepped out over rocks and roots firmly

and lightly as if their loads were nothing. This was the first train that

had ever passed through the cany6n without losing at least one animal. The

horse or mule puts its foot on a piece of innocent-looking moss;

underneath the moss there happens to be a wet stone over which he slips;

at the same moment, his broad unwieldly pack strikes against a rock,

outjutting from the bluff, and as there is no room for him to recover

himself, over he goes into the roaring Thompson, and that's the last seen

of him unless brought up by a tree halfway down the precipice. Two months

before a mule fell over in this way. The packers went down to the river

side to look for him, but as there was no trace to be seen, resumed their

march. Five days after, another train passing near the spot heard the

braying of a mule, and guided by the noise looked, and found that he had

fallen on a broad rock half way down, where he had lain for some time

stunned. Struggling to his feet, fortunately for him the apparaho got

entangled round the rock, and held him fast till he was relieved by the

men of the train from his razor bridge over the flood. This was a more

wonderful deliverance than that of Bucephalus when abandoned by Mr. O'B.

For several miles, the river here is one long

rapid, dashing over hidden and half-hidden rocks scattered over every part

of its bed. The great point of danger is reached at 'Hell Gate.' A huge

arch had once stretched across the present channel, and had been rifted

asunder, leaving a passage for the river not more than thirty feet wide.

The rock looked as if it had recently parted, a depression on the one side

exactly fitting into an overhanging rock opposite, as if it were possible

for a counter convulsion to groove and tongue the two together again.

Through this passage the river raged, and the whole force of the current

ran under the overhanging black rock, so near its roof that at high water

the river is forced back. From this point the Canyon continues for six or

seven miles down, at one point the opposing rocks being only fifteen feet

apart. The river there boils and spurts up as if ejected from beneath out

of an hydraulic pipe.

Half a mile below 'Hell Gate,' a bell was

again heard ahead. This, to our great delight belonged to a mule train

accompanying Mr. Marcus Smith—the deputy of the Engineer in chief on the

Pacific side. Our pack-horses were sent on while we halted to exchange

greetings and news. Mr. Smith was on his way to Tete Jaune Cache to try

and find a Pass across the Gold range. He had spent the greater part of

the summer on the Pacific coast, in the Cascades, and the Chilcoten

District in order to find a practicable line for the railway from Bute

Inlet through to Tete Jaune Cache. After a long consultation and a lunch

of bread and cheese—cheese produced by Smith and eaten so freely by us who

had not tasted any for two months, that Smith ruefully declared our lunch

to be "cheese—and bread," the Chief advised him to return with us to

Kamloops, as it was too late in the season to adventure into the heart of

the Gold range from the east side. It being also of importance that the

two should compare notes for a few days, the two parties became one.

Following up our pack-horses, we came in the

course of the next few miles to the bottom of the Canyon, and all at once,

to a totally different aspect of the river and road. The river ceases to

descend rapidly for the next twelve miles, and the valley opens out to a

breadth of two or three miles. The road runs through this level; but,

though a great improvement on the breakneck hills we had been going up and

down all day, the clumps of willow and alder stubs and roots kept the

horses from venturing on much beyond a walk,—except the Secretary's, a mad

brute called "the fool" which dashed on after the "bell' at such a rate

that the rest of the party in following more slowly looked round to pick

up the remains. The river here, as if exhausted with its furious racing,

subsides into a smooth broad lake-like appearance, and calmly reflects

everything on its banks-Hence the name of this district—"Stillwater." Four

miles along this brought us to our men unpacking the horses at the point

agreed on in the morning. Half a mile ahead, they said, were the tents of

the U. and V. parties who had been surveying all summer between Kamloops

and Tete Jaune Cache. They had met at this central point, the work on both

sections being just finished. Going on to their camp, we found Mr. John

Trutch, the engineer in change of both parties, and our friend V. Their

encampment seemed to us a great affair, unaccustomed as we had been for

weeks to new faces. Each party consisted in all of sixteen or eighteen

men, with two Indians,—one the cook's slavey, and the other—slavey to the

officer in charge, cabin boy, and general messenger. Besides the two

parties there was a third in charge of a pack train, so that the valley

was alive with men and mules;—all busy packing up to start for Kamloops in

the morning. Most cordial were the greetings on both sides. They at once

set to work to prepare supper for us, though they had had their own

already, and men were sent back to bring our tent down beside their

encampment. The latest news was eagerly asked and given. We heard for the

first time scraps of general election news, the item of most recent

interest being the election of Sir Francis Hincks as M.P. for the

Vancouver District; but the one that delighted us most being the victory

of the Canadian team at Wimbledon in the competition for the Rajah of

Kolapore's cup against the eight picked shots of the United Kingdom. The

names of the eight were read out, and a special cheer given for Shand of

Halifax who scored highest.

A mighty supper was soon announced, and as we

looked at the tent floor, laden with what to us were the rarest

delicacies, and knew that we had appetites to do full justice to them all,

one after the other, our hearts warmed within us. Never were men in better

condition for the table. Beefsteak, bacon, stuffed heart, loaf bread and a

bottle of claret; a second course of fried slices of the remains of a

plum-pudding with which they had entertained Mr. Smith the day before,

seasoned with blueberry jam made by themselves,—a feast for a king,—a

feast the memory of which shall long gladden us. There was so much to talk

and hear about, such a murmur of voices, the pleasant light of so many

fires, the prospect of a warm sound sleep, and of more rapid journeying

hereafter, that there was nothing wanting to make our happiness complete,

except letters from home, and those were at Kamloops, not far away.

September 25th.—Rose at 5.30 refreshed, and as

ready for a Highland breakfast as if we had not eaten an English dinner

last night. It was arranged that Mr. Trutch should accompany us to

Kamloops, V. remaining behind to bring on everything, and that at the

Clearwater River, sixty-two miles distant, we should take the survey boat,

and go down the Thompson for the remaining seventy-three miles to Kamloops.

As the Chief had letters to write to different

parties, it was nine o'clock before we got away from the pleasant

Stillwater Camp, bidding good-bye to V., not without the hope of soon

meeting him in Ottawa, for we heard that there was a probability that in

his absence, and without canvassing, he would be elected on this very day

as a member of the House of Commons. Our pack-horses had gone on two hours

before with instructions to camp at Round Prairie, twenty-five miles from

Stillwater. Soon

after starting, we caught up to the beef-cattle and the pack-train of

mules that had gone in advance with U's camp. As the trail is narrow and

mules resent being passed on the road —occasionally flinging their heels

back into the face of the too eager horse, it took some time and

engineering to get ahead; but when this was accomplished we moved at a

rapid walk, breaking now and then into a trot. From the canyon to Kamloops

the trail steadily improved. Our morning journey was for ten miles along

the grassy or willow covered meadow on the west side of the Thompson's

Stillwater. The river looked like a long lake. The sand over the trail and

the debris strewn around showed that, in some years at any rate, the river

overflowed the low meadow; but an embankment of very moderate height would

protect a railway line from all danger.

We halted for lunch at the south end of the

Stillwater, fortunately coming on U's advance party who supplied us with

some bread, while the Doctor produced two boxes of sardines he had

prudently "packed." One of the men, an old Ontarian, was diligently

perusing the Toronto Globe of August 9th; and as it contained the latest

news, he kindly presented it to the Chief. The paper, as was natural at

the season, was filled with electioneering items; but though we would have

preferred a larger infusion of European news, very little was left unread.

Another of the men gave Mr. Trutch a pair of willow grouse he had shot the

day before. British Columbia boasts of having seven or eight varieties of

the grouse kind, the most abundant being the sage hen, the blue grouse,

the ptarmigan, and the spruce partridge or fool-hen, that is oftener

knocked over with a stick than shot.

After its long repose the Thompson now begins

to brawl and prepare for another rush down hill. Its height above sea

level at the bottom of the canyon is 2,000 feet and at Kamloops 1,250. It

falls more than two-thirds of this 750 feet of difference in the

forty-five miles immediately above Clearwater. In the seventy-three miles

below Clearwater the fall is only 240 feet. The meadow now ceased, and the

valley contracted again. We could easily understand the dismay with which

Milton and Cheadle beheld such a prospect. The valley had opened before,

below Mount Cheadle, as if the long imprisonment of the river, and with it

their own, was coming to an end; but the Great Cany6n had hedged it in

again more firmly than ever. Next at Stillwater and down for twelve or

fourteen miles, everything looked as if the river wearied with its long

course between high overhanging hills, was at last about to emerge into an

open country of farms and settlements; but again the hills closed in, and

the apparently interminable narrow valley recommenced.

There was no gloom, however, in our party. No

matter what the road, the country, or the weather, everything was on our

side; fair trail, friendly faces, commissariat all right, and the prospect

of a post office before the end of the week. The day too was warm and

sunny; the climate altogether different from the rainy skies and cold

nights higher up the slope; and we were assured that an hundred miles

farther down stream, no rain ever fell except an occasional storm or a few

drops from high passing clouds,—an assurance more welcome to us than to

intending settlers.

The aspect of the hills too was changing. They were lower and more broken,

with undulating spaces between, giving promise of escape to the imprisoned

traveller, sooner or later. Distinctly defined benches extended at

different points along the banks, and on these the trail was comparatively

level. About 4 P.M. we came to a bit of open called "Round Prairie," and

found the men unpacking for the night, as there was no other good place

for the horses nearer than sixteen miles off.

This had been the easiest day's journey since

entering the mountains, for though we had travelled twenty-four miles,

there was no fatigue, so that it was really like one of the pic-nic days

of the plains. The early camping gave another chance to read the papers,

of which every one took advantage, though it seemed odd to be devouring

with avidity papers nearly two months old.

September 26th.—It rained

heavily this morning, and the start from camp was made with the delays and

discomforts that rain produces. The cotton tent weighes thrice as much as

when dry. The ends of the blankets, clothes, some of the food, the

shaganappi, etc. get wet. The packs are heavier and the horses' backs are

wet; and it is always a question whether or not water-proofs do the riders

any good. This morning one of the pack-horses could not be found.

Everything had to be packed on the three others; Jack remained behind to

look for the fourth, and soon found the poor brute sheltered from the

rain, in a thicket near where "the bell" had been.

The country to-day resembled that of

yesterday; but even where it opened out, the steady drizzle and the heavy

mists on the hills hid everything. Cedars had entirely disappeared, and

the spruce and pines were comparatively small. The aralea gave place to a

smaller leaved trailer with a red berry like the raspberry; and a dark

green prickly-leaved bush like English holly, called the Oregon grape, and

several grasses and plants new to us covered the ground.

Six miles from camp we came to Mad River, a

violent mountain affluent of the Thompson, crossed by a good bridge; and

ten miles farther on to "Pea Vine Prairie," where as the rain ceased and

enough blue sky "to make a pair of breeches" showed, the halt for dinner

was called. Here we saw for the first time the celebrated "bunch-grass,"

which has no superior as feed for horses or cattle; especially for the

latter, as the beet that has been fed on it is peculiarly juicy and

tender. The name explains its character as a grass. It consists of small

narrow blades—ten to fifty of them growing in a bunch from six to eighteen

inches high, and the bunches so close together in places that at a

distance they appear to form a sward. The blades are green in spring and

summer, but at this season they are russet grey, apparently withered and

tasteless, but the avidity with which the horses cropped them, turning

aside from green and succulent marsh grass and even vetches, showed that

the virtue of the bunch grass had not been lost.

The clouds now rolled up like curtains from

the hills, and the sun breaking out revealed the river, three or four

hundred feet below, with an intervale on each side that made the valley at

least two miles across to the high banks that enclosed it. There was a

bend in the river to the west, so that we saw not only a little up and

down, which is usually all that can be seen on the North Thompson, but

round the corner; a wide extent of landscape of varied beauty and soft

outlines. The hills were wooded, and the summits of the highest dusted

with the recent snow, that had been rain-fall in the valley. Autumn hues

of birch, cottonwood, and poplar blended with the dark fir and pine,

giving the variety and warmth of colour that we had for many days been

strangers to, and which was therefore appreciated by us all the more. The

face of the bank on which we stood presented a singular appearance. It was

of whitish clay mixed with sand, the front hard as cement by the action of

the weather; there had been successive slides of the bank behind in

different years, but the old front had remained firm, and was now standing

out along the face, away from the bank, in pyramidal or grotesque forms,

like the trap or basalt rocks, spires, and columns along the east coast of

Skye, springing from debris at the base. Similar strange forms of cemented

whitish clay are to be found in several places on the Fraser.

As Smith and Trutch now messed with us, the

different cooks contributed to the common stock and to the cooking, with

the two advantages of greater variety to the table, and greater speed in

the preparation. After a short halt at "Pea Vine" we got into the saddle

again, and made ten miles before sunset; the trail leading across sandy

benches intersected by numerous little creeks, the descent to which was

generally so direct that every one had to dismount, both for the down and

the up hill stretch. Camp for the night was pitched at one of these

creeks, twelve miles to the north of the Clearwater, and Frank who had

become quite an adept at constructing camp fires, built up a mighty one,

at which we dried wet clothes and blankets. Our camp presented a lively

scene at night. Great fires before each tent lit up the dark forest, and

threw gleams of light about, that made the surrounding darkness all the

more intense. Through the branches of the pines, the kindly stars—the only

spectators— looked down on groups flitting from tent to tent, or cumbered

about the many things that have to be cared for even in the wilderness,

cooking, mending, drying, overhauling baggage, piling wood on the fire,

planning for the morrow, or "taking notes." How like a lot of gypsies we

were in outward appearance, and how naturally every one took to the wild

life! A longing for home and for rest would steal over us if we were quiet

for a time, but a genuine love for camp life, for its freedom and

simplicity and rude happiness, for the earth as a couch and the sky for a

canopy, and the wide world for a bed-room, possessed us all; and we knew

that, in after days, memory would return, to dwell fondly over many an old

camping ground by lake or river side, on the plains, in the woods, and

among the mountains.

September 27th.—Six miles travel like yesterday's brought us this morning

to Raft River, a broad stream, whose ice cold pellucid waters, indicated

that it ran from glaciers, or through hard basalt or trap rock that

yielded it no tribute of clay to bring down; and six miles more along

gravelly benches to the Clearwater, whose name is intended to express a

similar character, and the difference between itself and the clay coloured

Thompson it empties into. The Clearwater is so large a stream that after

its junction, the Thompson becomes clearer from the admixture. At the

junction there is a depot of the Canada Pacific Railway Survey, with a man

in charge, and a three ton boat used to bring up supplies from Kamloops,

which we had arranged with V. to take down, leaving Jack and Joe to bring

along the horses, at a leisurely pace. From Clearwater to Kamloops by the

trail is between seventy and eighty miles, and by the river probably

ninety. Aided by the current we hoped to row this in a day and a half, and

so get to Kamloops on Saturday night. V. had given us four men to row the

boat, and as she lay at the river bank, the loads were taken from the

horses' backs, and thrown in without difficulty.

After dining in front of the shanty, we said

"good-bye" to Jack and Joe, and gave ourselves up to the sixth lot of men,

we had journeyed with since leaving Fort Garry, and the fourth variety of

locomotion; the faithful Terry still cleaving to the party, and really

seeming to get fond of us, from force of habit, and the contrast of his

own long tenure of service with the short periods of all the others.

At two P.M., twelve got into the boat; our

five, the crew, Smith, Trutch, and his man Johnston who was to steer and

help Terry. Up to two o'clock the day had been cloudy and cold, but the

sun now came out, and we could enjoy the luxury of sitting in comfort,

talking or reading, knowing too that no delay was occasioned by the

comfort. The oars were clumsy, but the men worked with a will, and the

current was so strong that the boat moved down at the rate of five or six

miles an hour, so that after four and a half hours, Trutch advised

camping, though there was still half an hour's twilight, for at the same

rate we would easily reach Kamloops on the morrow.

In this part of its course the river did not

seem materially larger, or different from what it was much farther up. It

still ran between high rugged hills, that closed in as canyons at

intervals. Its course was still through a gorge rather than a valley. Any

expanse was as often up on a high terrace, that had once been its bed, as

down along its present banks. Seventeen miles from the Clearwater we

passed the "Assineboine's bluff," a huge protuberance of slate that only

needs a similar rock on the other side, to make it a formidable canyon. At

some points the forms of the hills varied so much that the scene was

picturesque and striking, but these hills are merely outliers, and not

high enough to impress, or to do away with the feeling of monotony.

Besides, we had been so sated with mountains that it needed much more to

attract our admiration now than would have sufficed a month ago.

Our crew were expert in managing a boat and in

putting up a tent. Before dark everything was secured, and we were

enjoying our pork and beans, with a plate of porridge before and after the

heavier dish; and soon after supper lay down, as we expected, for the last

time in this expedition—in our "lean to"—sub Jove frigido. This—our

'Thompson River Camp'—was the 60th from Lake Superior, and as we wrapped

the blankets round us, a regretful feeling that it would probably be the

last, stole into every one's mind.

September 28th.—Raining this morning again,

but as there were no horses to pack, it was of less consequence. By 7.30

the boat was unmoored and we were rowing down the river, having fifty-two

miles by the survey line and probably sixty-five by the river to make, if

at all possible, before night. Behind and above us the clouds were heavy,

but we soon passed through the rainy region, to the clearer skies that are

generally in the neighbourhood of Kamloops. For the first half of our way

the river scenery was very similar to that of yesterday, except that the

flats along the banks were broader and more fertile, and the hills covered

more abundantly with bunch grass. A few families of "Siwashes," as Indians

on the Pacific slope are universally called; in the barbarous

Chinook,—probably from "Sauvages," are scattered here and there along the

flats. Their miserable little tents looked like salmon smoking

establishments ; for as the salmon don't get this far up the river till

August and September, the Siwashes have to catch and dry them for winter

use very late in the year.

Small pox has reduced the number of Siwashes

in this part of the country to the merest handful. A 6ight of one of their

winter residences, is a sufficient explanation of the destructiveness of

any epidemic that gets in among them. A deep and wide hole is dug in the

ground, a strong pole with cross sticks like an upright ladder stuck in

the centre, and then the house is built up with logs, in conical form,

from the ground to near the top of the pole, space enough being left for

the smoke and the inmates to get out. Robinson Crusoe like, instead of a

door, they use the ladder, and go in and out of the house during the

winter, by the chimney. As this is an inconvenient mode of egress they go

out as seldom as possible; and as the dogs live with the family, the filth

that scon accumulates can easily be estimated, and so can the consequence,

should one of them be attacked with fever or small pox. They boast that

these houses are "terrible warm," and when the smoke and heat reach

suffocation point, their simple remedy is to rush up the ladder into the

air, and roll themselves in the snow for a few minutes. In spring they

emerge from their hybernation into open or tent life; and in the autumn,

they generally find it easier to build a new house or bottle to shut

themselves up in, than to clean out the old one. This practice accounts

for the great number of cellar-like depressions along the banks of the

river; the sites of former dwellings resembling the sad mementoes of old

clans to be seen in many a glen in the Highlands of Scotland, and

suggesting at the first view that the population in former years had been

very large. But as one Siwash family may have dug out a dozen residences

in as many years, the number of houses is no criterion of what the tribe

numbered at any time.

For the first ten or fifteen miles of to-day's

course, the river ran rather sluggishly. The current then became stronger,

and as it cut for several miles through a range of high hills that had

once stretched across its bed, there was a series of rapids powerful

enough to help us on noticeably, and of course to hinder much more a boat

going upstream. The valley here became a gorge again. Emerging from the

range at mid-day, Trutch pointed out blue hills in the horizon, apparently

forty or fifty miles ahead, as beyond Kamloops. We halted for twenty

minutes to take a cold lunch, and then moved on.

An hour before sunset we came to the first

sign of settlers,—a fence run across the intervale from the river to the

mountain, to hinder the cattle from straying farther up. Between this

point and Kamloops there are now ten or eleven farms or "ranches" as they

are called on the Pacific slope, all of them taken up since Milton and

Cheadle's time. The first building was a saw-mill about fifteen miles from

Kamloops, the proprietor of which was busy sawing boards to roof in his

own mill, to begin with. Small log cabins of the new settlers, each with

an enclosure for cattle called "the corral" close to it, next gladdened

our eyes, so long unused to seeing any abodes of men. For all time, the

names and technical expressions on the Pacific coast are likely to show

that settlement proceeded from the south and not across the mountains. But

such Californian terms as 'ranch,' 'corral' and others from the lips of

Scotchmen sounded strangely in our ears at first.

Stock raising is the chief occupation of

farmers here; for though the ground produces the very best cereals and

vegetables, irrigation is required as in the fertile plains and valleys of

California; and the simplest methods of irrigating—even where a stream

runs through the farm—are expensive in a country where farm labourers and

herdmen get from $30 to $75 a month and their 'board'; and where stock

raising pays so well on account of the excellence of the natural grass.

Common labourers on the roads in British Columbia get $50 a month, about

$20 of which they pay for 'board'; and teamsters and packers from $100 to

$150. The farmers who

have settled on the North or South Thompson are making money; and beef

commands higher prices every year. As there are very few white women, most

of the settlers live with squaws, or Klootchmen as they are called on the

Pacific ; and little agricultural progress or advance of any kind can be

expected until immigration brings in women, accustomed to dairy and

regular farm-work, to be wives for white men.

The ranches taken up are near little creeks

that supply water to irrigate them. In the valley of the South Thompson

are large extents of excellent land beside, fit at once for the plough,

that will not be settled on, till it is proved that water can be

profitably raised from the river, or be had from wells in sufficient

quantity. Neither way has yet been tried, simply because all the land

along the creeks has not yet been taken up, and there has been no

necessity for experimenting.

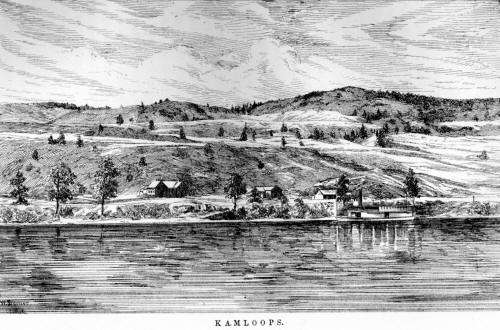

As we drew nearer Kamloops, characteristics of

a different climate could be noted with increasing distinctness. A milder

atmosphere, softer skies, easy rolling hills ; but the total absence of

underbrush and the dry grey grass everywhere covering the ground were the

most striking differences to us, accustomed so long to the broad-leaved

underbrush and dark green foliage of the humid upper country. We had

clearly left the high rainy, and entered the lower arid, region. The

clouds from the Pacific are intercepted by the Cascades, and only those

that soar like soap-bubbles over their summits pass on to the east. These

float over the intervening country till they come to the second range, a

region high enough to intercept them. Thus it is that while clouds hang

over Kamloops and its neighbourhood, little rain or snow falls. The only

timber in the district is a knotty red pine, and as the trees grow widely

apart, and the bunch-grass underneath is clean, unmixed with weeds and

shrubs, and uniform in colour, the country has a well-kept park-like

appearance, though there is too little of fresh green and too many signs

of aridity for beauty.

The North Thompson runs smoothly for ten miles

above Kamloops, after rippling over a sudden descent, and making a sharp

bend round to the north-west and back again to the south. In the afternoon

a slight breeze had sprung up, and a tent was hoisted for a sail: but the

wind shifted so frequently that more was lost than gained by it, and at

sunset we took it down and trusted to the heavy clumsy oars. We had only

four or five miles to make when it became so dark that the shoals ahead

could not be seen; and as none of the crew knew this part of the river,

the steering became mere guess-work, and the doctor as the lucky man was

put at the helm. We grounded three or four times, but as the boat was

flat-bottomed, and the bed of the river hard and gravelly, she was easily

shoved off. The delays were provoking, all the more because there might be

many of them; but about 8 o'clock, the waters of the South Thompson,

running east and west, gleamed in the darkness at right angles to our

course. The North branch, though the largest, runs into the South branch.

A quarter of a mile down stream from the junction is Fort Kamloops.

The boat was hauled in to the bank; and Trutch

went up to the Fort. Mr. Tait, the agent, at once came down, and with a

genuine H. B., which is equivalent to a Highland, welcome, invited us to

take up our quarters with him. Gladly accepting the hospitable offer, we

were soon seated in a comfortable room beside a glowing fire. We were at

Kamloops! beside a Post Office, and a waggon road ; and in the adjoining

room, the half-dozen heads of families resident in or near Kamloops were

holding a meeting with the Provincial Superintendant of Education, to

discuss the best means of establishing a school. Surely we had returned to

civilization and the ways of men!

Were we to judge from what we have seen of the

country along the Fraser and Thompson rivers, the conclusion would be

forced on us that British Columbia can never be an agricultural country.

We have not visited, however, the Okanagan and Nicola Districts, or the

Chilcoten Plains; and we have heard good accounts of the fertility of the

former, and the rich parklike scenery of extensive tracts in the latter.

But the greater part of the mainland is, "a sea of mountains"; and the

Province will have to depend mainly on its rich grazing resources, its

valuable timber, its fisheries, and minerals, for any large increase of

population. Even that part of the country lying between the second range

of "the Rockies" and "the Cascades" where we now are, is an elevated

plateau, broken by hills. The indications are that it once was submerged

under water, with the hill tops then showing as islands, and with the long

line of the Cascades separating the great elevated lake from the sea. In

process of time clefts riven in the Cascades made ways for the waters to

escape. By these clefts the Fraser, the Homathco, the Skeena, and the

Bella Coula now run in deep gorges through granite and gneissic or trap

and basalt rocks to the sea. Originally the waters emptied by a series of

falls the magnificence of which it is scarcely possible to conceive. The

successive subsidences of the water are now shown by the high benches of

gravel and silt along the river valleys, and on account of the great depth

cut down by the rivers, there are no bottom

lands or meadows worth speaking of. As a general rule, with only a few

exceptions, all the water channels are found in deep gorges, and for this

reason the great rivers of the Province cannot overflow their banks. They

must be content with rising higher up the steep hill-sides, between which,

for the greater part of their course, they are pent. |