|

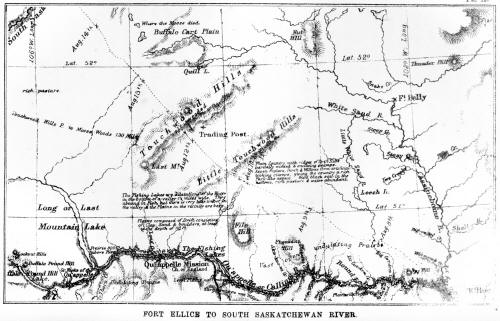

Fine fertile country.—The

water question.—Duck shooting.—Salt Lakes.—Camping on the plains.—Fort

Ellice.—Qu'appelle Valley.—"Souzie."—The River Assiniboine.—The

Buffalo.—Cold nights.—Rich soil.—Lovely Country.—Little Touchwood

Hills.—Cause of prairie fires.—A day of rest.—Prairie uplands.—Indian

family.—Buffalo skulls.— Desolate tract.—Quill Lake.—Salt water.—Broken

prairie.—Round hill.—Prairie fire.—Rich black soil.—Magnificent

Panorama.—Break-neck speed.—The South Saskatchewan. — Sweethearts and

wives.— Fort Carlton. —Free traders.— The Indians.—Crop raising.

August 5th.—This morning it

rained heavily, and delayed us a little; but, by the time we had our

morning cup or pannikin of tea, the carts packed, and everything in its

place, the weather cleared up. We got away at 5 A.M., and rode sixteen

miles before breakfast; reaching "Pine Creek," a favorite camping ground;

still following up the course of the Assiniboine, though never coming near

enough to get a sight of it, after leaving our first camp from Fort Garry.

The next stage was fourteen miles to 'Bog Creek,' and, after dinner,

eleven miles more, making forty-one for the day. Instead of the level

prairie of the two preceding days, and the black peaty loam, we had an

undulating and more wooded country, with soil of sandy loam of varying

degrees of richness. Here and there ridges of sand dunes, covered,

however, with vegetation, sloped to the south, having originally drifted

from the north, probably from the Riding Mountains of which they may be

considered the outlying spurs. From the top of any one of these, a

magnificent view can be had. At our feet a park-like country stretched far

out, studded with young oaks ; vast expanses beyond, extending on the

north to the Riding Mountains, and on the south to the Tortoise Mountain

on the boundary line; a beautiful country extending hundreds of square

miles without a settler, though there is less bad land in the whole of it

than there is in the little peninsula of Halifax, or within five or ten

miles of any of our eastern cities. This almost entire absence of

unproductive land is to us very wonderful. If we except the narrow range

of sandhills, there is actually none ; for the soil, even at their base,

is a light sandy loam which would yield a good return to the farmer. The

soil about these hills is not what is usually termed prairie, and is not

equal to prairie. Its flora is not that of the prairie. Both soil and

flora are like those of the Rice Lake plains, and the County of Simcoe in

Ontario, where excellent wheat crops are raised. The only question,

suggestive of a doubt, that came up was the old one of "Is there plenty of

water?" The rivers are few; the creeks small. Along their banks there is

no difficulty, but what of the intervening ground? We had heard of wells

sunk in different places, and good water found from four to fifty feet

down. But, yesterday, Grant informed us that a beautiful stretch of

prairie, immediately to the west of his location, which had been taken up

by a friend of his, had been abandoned because no water could be got. They

had sunk wells in three places, one of them to the depth of seventy-five

feet, but pierced only hard white clay. Grant believed that this stratum

of clay extended over a limited area, and that, under it, water would be

tapped if they went deep enough. But the matter is of too great importance

to be left to conjecture. Test-wells should be sunk by the Government in

different places; and even where there are saline or brackish lakes, or

even should the first water tapped prove saline, artesian wells might be

tried, so as to get to the fresh water beneath. Till it is certain that

good water can be easily had all over the prairie, successful colonization

on a large scale cannot be expected. The general belief is that there is

water enough everywhere. There is an abundant rain fall, and the water

does not form little brooks and run off, but is absorbed by the rich,

deep, porous ground. Still the claims of our North-west on the attention

of emigrants would be rendered all the stronger, were they assured that

the water supply was unfailing everywhere. Up to this time the question

has not been started, because much of the land on the river-banks has not

yet been taken up. But it would be well to be prepared with an answer.

Nothing could be more exhilarating than our

rides across the prairie, especially the morning ones. The weather, since

our arrival at Fort Garry, had been delightful, and we knew that we had

escaped the sultry heat of July, and were just at the commencement of the

two pleasantest months of the year. The nights were so cool that the

blanket was welcome, and in the evenings and mornings we could enjoy the

hot tea. The air throughout the day was delicious, fresh, flower-scented,

healthful, and generally breezy, so that neither horse nor rider was warm

after a fifteen or twenty miles' ride. We ceased to wonder that we had not

heard of a case of sickness in one of the settlers' families. Each day was

like a new pic-nic. Even the short, terrific, thunder storm of the day

before yesterday had been enjoyed because of its grandeur. Grant told us

that it was the heaviest he had ever seen in the country, and that we had

felt its full force. Three miles away there had been no hail.

August 6th.—Up before four A.M., but were

delayed some time by the difficulty of lassoing the horses that were

wanted. The Doctor had, meanwhile, some shooting round the little lake by

which we had camped ; and getting some more on the way, Terry, the cook,

was enabled to serve up plover, duck and pigeons, with rice curry for

breakfast. Our morning's ride was sixteen miles, and brought us to the

Little Saskatchewan,—a swift-flowing pebbly-bottomed stream, running south

into the Assiniboine. Its valley was about two miles wide and two hundred

and fifty feet deep. All the rivers of the North-west have this

peculiarity of wide valleys, and it constitutes a serious difficulty in

the way of railroad making; they must be crossed, but regular bridging on

so gigantic a scale is out of the question. The hill sides sloping down

into the valley or intervale of the river are green and rounded, with

clumps of trees, most of them fire-scorched, in the depressions.

We hailed the sight of this flowing stream

with peculiar delight; for it was the first thing that looked, to our

eyes, like a river in all the hundred and twenty miles since leaving the

Assiniboine. The creeks crossed on the way were sluggish and had little

water in them, and most of the swamps and lakelets were dried up, and

their bottom covered with rank coarse grass, instead of the water that

fills them in the spring. This morning, however, we passed by several

pretty-well-filled lakes,— plover and snipe about most of them—on the

"height of land," from which the ground slopes toward the Little

Saskatchewan. Our

second stage for the day was only eleven miles; but the next was fourteen,

and we drove or rode along the winding road at a rattling pace, reaching

our camping ground, at Salt Lake, an hour before sunset. This lake is

bitter or brackish, but, on the opposite side of the road, there is good

water; and, although the mosquitoes gave us a little trouble, here we

fared well—as at all our camps. This was the first saline lake we had

seen, but farther north on the way to Edmonton, there are many such; and

grievous has been the disappointment of weary travellers, on drawing near

to one of them and preparing to camp. The causes are probably local, for

good water is found near, and, all around, the grass is as luxuriant as

elsewhere. A white crust forms on the dried up part of the bottom and the

shores are covered with marine plants, chiefly reddish-colored, thick,

succulent samphire and sea-blite growing together and extending over

several acres of ground. The salt in these lakes is sulphate of soda.

A bathe in the little Saskatchewan before

breakfast was our first good wash for two or three days, and we enjoyed it

proportionately. Our horses did their forty-one miles to-day, seemingly

with greater ease than they had any previous day's work. Most of them are

of pure native breed; some of them—the largest— have been crossed with

Canadian, and the swiftest with Yankee breeds. In all our pack there are

only two or three bad horses; none of them looked well at first, but,

though small and common looking, they are so patient, hardy and

companionable, that it is impossible for their riders to avoid becoming

attached to them. Hardly two of the saddles provided for our party were

alike. There was choice of English, American, and Mexican military,—the

first kind being the general favorite.

August 7th.—Made a good day's journey of

forty-five miles, from the Salt Lake to the junction of the Qu'Appelle and

Assiniboine rivers. The first stage was ten miles, to the "Shoal Lake"—a

large and beautiful sheet of water with a pebbly or sandy beach—a capital

place for a halt or for camping. The great requirements of such spots are

wood, water, and feed for the horses ; the traveller has to make his

stages square with the absence or presence of those essentials. If he can

get a hilly spot where there are few mosquitoes, and a sheet of water

large enough to bathe in, and a resort of game, so much the better.

Arrived at the ground, the grassiest and most level spots, gently sloping,

if possible, that the head may be higher than the feet, are selected. The

tents are pitched over these, one tent being allotted to two persons, when

comfort is desirable, though sometimes a dozen crowd inside of one. A

waterproof is spread on the ground, and, over that, a blanket. Each man

has another blanket to pull over him, and he may be sound asleep ten

minutes after arriving at the ground, if he has not to cook or wait for

his supper. The horses need very little attention; the harness is taken

off and they are turned loose—the leaders or most turbulent ones being

hobbled, i. e., their fore feet are fettered with intertwined folds of

shaganappi or raw buffalo hide, so that they can only move about by a

succession of short jumps. Hobbling is the western substitute for

tethering. They find out, or are driven to, the water, and, immediately

after, begin grazing around ; next morning they are ready for the road. A

morning's swim and wash in Shoal Lake was a great luxury, and the Doctor

had some good shooting at ducks, loons, yellowlegs, and snipe.

Our second stage was twenty-one miles to

"Bird's Tail Creek," a pretty little running stream, with valley nearly as

wide, and banks as high, as the Little Saskatchewan. It is wonderful to

see the immense breadth of valley that insignificant creeks, in land where

they have not to cut their way through rocks, have eroded in the course of

ages. At this creek,

we were only twelve miles distant from Fort Ellice. The true distance from

Fort Garry, as measured by our odometer being two hundred and fifteen

miles, and not two hundred and thirty-one, as stated on Palliser's map and

by Captain Butler in his book. As our course lay to the north of Fort

Ellice, the Chief and two of the party went on ahead to get provisions and

half a dozen Government horses that had been left to winter there, and to

attend to some business, while the rest followed the direct trail and

struck the edge of the plateau overlooking the Assiniboine,—which was

running south —just where the Qu'Appelle joined it from the west. The view

from this point is magnificent; between two and three hundred feet below,

extending far south and then winding to the east, was the valley of the

Assiniboine,—at least two miles wide.

Opposite us, the Qu'Appelle joined it, and

both ran so slowly, that the united river meandered through the intervale,

as circuitously as the links of the Forth, cutting necks and promontories

of land that seemed, and were, almost islands, some of them soft and

grassy, and others covered with willows or timber. The broad open valley

of the Qu'Appelle stretched along to the west, making a grand break in

what would otherwise have been an unbroken plateau of prairie. Three miles

to the south of this valley, and therefore opposite us but farther down,

two or three small white buildings on the edge of the plateau were pointed

out as Fort Ellice. To the north of the Qu'Appelle, the sun was dipping

behind woods far away on the edge of the horizon, and throwing a mellow

light on the vast expanse which spread around in every direction.

We descended to the intervale by a

much-winding path, and moved on north a little to the "crossing" three

miles above the Fort, and immediately above where the Qu'Appelle flows

into the main river. Scarcely had the tents been pitched and the fires

lighted, when the Chief appeared bringing supplies of flour, pemmican,

dried meat, salt, etc., from Fort Ellice. He reported that there were

several parties of Indians about the Fort, who had emigrated two or three

years ago from the United States, anxious to settle in British territory.

One of them, from Ohio, spoke good English, and from him he gained the

information about them.

The first portion of the journey from Fort

Garry is considered to extend to Fort Ellice, and we had accomplished it

in less than six days. The last stage had been over the worst road—a road

winding between broad hill-sides strewn with granite boulders, and lacking

only brawling streams and foaming fells to make it like Moffatdale, and

many another similar dale in the south of Scotland. But here there never

had been bold moss troopers, and there were no "Tales of the Borders."

Crees, and Sioux and Ojibbeways may have gone in the war path against each

other, and have hunted the buffalo over the plains to the west, but there

has been no Walter Scott or even Wilson to gather up and record their

legends, and hand down the fame of their braves. And there are no sheep

grazing on those rich hill-sides, and there was neither wigwam, steading,

nor shieling on the last hundred and sixty miles of road. Silence reigned

everywhere, broken only by the harsh cry of wild fowl rising from lakelets,

[or the grouse-like whirr of the prairie hen on its short flight. We had

seen but a small part, and that by no means the best of the land. The

trail follows along the ridges, where there is a probability of its being

dry for most of the year, as it was not part of its object to shew the

fertility of the country or its suitableness for settlers. But we had seen

enough to show that, even east of Fort Ellice, there is room for a large

population. Those great breadths of unoccupied land are calling 'come,

plough, sow, and reap us.' The rich grass is destroyed by the autumn

fires, which a spark kindles, and which destroy also the wood, which

formerly was of larger size and much more abundant than now. This

destruction of wood seriously affects the water supply. Lakes that once

had water all the year round are now dry, except in the spring time. But,

when settlers come in, all this shall be changed. The grass will be cut at

the proper time, and stacked for the cattle, and then there shall not be

the wide spreading dried fuel to feed the fires, and give them ever

increasing force. Fields of ploughed land, interspersed here and there,

shall set bounds to the flames, and tourists and travellers will be less

likely to leave their camp-fires burning, when they know that there are

settlers near, whose property would be endangered, and who therefore would

not tolerate criminal carelessness on the part of strangers.

8th August.—Being in the neighbourhood of a

fort, and having to re-arrange luggage and look after the new horses, we

did not get away till nine o'clock. An hour before, greatly to the

surprise of Emilien,—for he had calculated on keeping in advance the

twenty-two miles he had gained on Sunday,—and greatly to our delight, Mr.

McDougal drove up and rejoined us with his man "Souzie." Souzie had never

been east before, and the glories of Winnepeg had fairly dazzled him. He

was going home heavy-laden with wonderful stories of all he had seen ;—

the crowd hearing Mr. Punshon preach and the collection taken up at the

close, the review of the battalion of militia, the splendour of the

village stores, the Red River steamboat, the quantities of rum, were all

amazing. When the plate came round at the church Souzie rejoiced, and was

going to help himself, but, noticing his neighbors put money in, he was so

puzzled that he let it pass. He chuckled for many a day at the simplicity

of the Winnepeggers:—"Who ever before saw a plate handed round except to

take something from it?" The review excited his highest admiration:—"Wah,

wah! wonderful! I have seen a hundred men turned into one!"

Our first work this morning was to cross the

Assiniboine. The ford was only three feet deep, but the bottom was of

shifting sand, so that it did not do to let the horses stand still while

crossing. The bank on the west side is bold, and the sand so deep, that it

is a heavy pull up to the top. After ascending, we moved west for the

first few miles along the north bank of the Qu'Appelle. The Botanist went

down to the intervale and sand-hills near the stream, to inspect the

flora, and was rewarded by finding half-a-dozen new species. We soon

turned in a more northerly direction, though, had there been a fortnight

to spare, some of us would have liked to have gone a hundred miles up the

Qu'Appelle, where, we had been told yesterday by a Scotch half-breed,

called Mackay, that the buffalo were in swarms. Mackay was on his way back

to Fort Garry with the spoils of his hunt. He had left home with his wife

and seven children and six carts, late in May, joined a party at Fort

Ellice and gone up to the high plains, where the source of the Qu'Appelle

is, near the elbow of the South Saskatchewan, and obtained his food for

the year in the way most pleasing to a half-breed. They had all lived

sumptuously while near the buffalo, and when they had dried enough meat to

fill their carts, at the rate of ten buffalos to a cart, they parted

company; and he and his wife, with the meat and skins, turned homewards,

to do little for the rest of the year, but enjoy themselves. This is all

very well when the buffalo are plenty ; but as they get scarcer or move

farther away, what is to be done? A man cannot be both a hunter and a

farmer; and, therefore, as the buffalo go west, so will the half-breeds.

But, fascinating as a buffalo-hunt seemed,

described in all the glowing language and gesticulations of a successful

hunter, the time could not be spared, and so we jogged along our road,

hoping that we might fall in with the lord of the prairies as far north as

Carlton or Fort Pitt.

The first part of the day's ride, like the

last part of the previous day's, was over the poorest ground we had

seen—light and sandy—and yet the grass nowhere presented the dried up,

crisp, brownish look that is so often seen in the eastern provinces at

this time of the year. Still the land about Fort Ellice is not to be

recommended, especially when there is so much of the very best waiting to

be cultivated. Nine

miles from the Assiniboine, we breakfasted beside a spring in the marsh

where the water is good, but where a barrel or some such thing, sunk in

the ground, would be desirable. This is every traveller's business, and,

therefore, is not done. We are now in "No man's Land;"—where the Governor

of Manitoba has a nominal jurisdiction, but where there are no taxes and

no laws ; where every man does what is right in his own eyes, and prays

that the great Manitou would prosper him in his horse, stealing or

scalping expeditions.

Our next stage was twenty-two miles to "Broken

Arm River" —a pretty little stream with the usual deep and broad valley.

The soil improved as we travelled west. The grass was richer, and much of

the flora that had disappeared for the previous twenty miles began to show

again. On the banks of the river there was time before tea to indulge in a

great feast of raspberries, as we camped early in the evening, after

having travelled only thirty-one miles. The Botanist had found exactly

that number of new species,—the largest number by far on any one day since

leaving Fort Garry. The explanation is, that he had the valleys of two

rivers and several varieties of soil to botanize over.

August 9th.—Last night the thermometer fell to

34°, and we all suffered from the cold, not being prepared for such a

sudden change. There was heavy dew, as there always is on prairies, and at

four o'clock, when we came out of the tents, shivering a little, the cold

wet grass was comfortless enough; but a warm cup of tea around the camp

fire put all right. We were on horseback before sunrise, and a trot of

thirteen miles, over a beautiful and somewhat broken country, fitted us

for breakfast. Mr. McDougal told us that in the elevated part of the

country in which we were, extending north-west from Fort Ellice, light

frosts were not unusual in July or August. They are not so heavy as

seriously to injure grain crops; but still they must be regarded as an

unpleasant feature in this section of the country. The general destruction

of the trees by fires makes a recurrence of these frosts only too likely,

till some action is taken to stop the real fountain of all the evils. If

there were forests, there would be a greater rainfall, less heavy dews,

and probably no frosts. But it will be little use for the government to

issue proclamations in reference to the extinguishing of camp-fires, until

there are settlers here and there, who will see to their observance for

their own interest. Settlers will plant trees, or give a chance of growing

to those that sow themselves, cut the grass, and prevent the spread of

fires. But settlers will not come, till there is a railroad to bring them

in. Our second stage

for the day was sixteen miles over an excellent road and through a country

that evoked spontaneous bursts of admiration from every one. The prairie

was more than rolling, it was undulating; broken into natural fields by

the rounded hillocks and ridges crowned with clumps of aspens —too often,

alas ! fire-scathed. In the hollows grew tall, rich, grass which would

never be mowed; everywhere else, even on the sandy ridges, was excellent

pasture. We met a

half-breed travelling, with dried meat and buffalo, skins, to Fort Garry,

in his wooden cart covered with a cotton roof, and he informed us that men

were hunting, two days' journey ahead, about the Touchwood Hills. This

excited our men to the highest pitch, for the buffalo have not come on

this route for many years, and eager hopes were exchanged that we might

see and get a shot at them. Wonderful stories were told of the

buffalo-hunts in former days, and men, hitherto taciturn, perhaps because

they knew little English (more, however, than we knew of French or Indian,

which they all spoke fluently) began explaining volubly—eking out their

meaning with expressive gesticulation,—the nature of a buffalo hunt. Fine

fellows all our half-breeds were as far as riding, hunting, camping,

dancing and such like were concerned; though they would have made but poor

farm-servants. Two of them had belonged to Riel's body-guard in the days

of his little rebellion. The youngest was Willie, a boy of sixteen, who

rode and lassoed, and raged, and stormed, and swore on the slightest

provocation, better than any of them. He looked part of the horse when on

his back, and never shirked the roughest work. We were horrified at his

ready profanity however, and the Doctor rowed him up about it; but, though

they all liked the Doctor, for he had physicked two or three of them

successfully, and had even bound up the sore leg of one of the horses

better than they could, the jawing had no effect. The Secretary then tried

his hand. Finding that Willie believed in his father, an adventurous

daring Scot, who had married a squaw, he accosted him one day when none of

the others were near, with, "Willie, would you like to hear me yelling out

your father's name, with shameful words among strangers?" He looked up

with a half-puzzled, half-defiant air, and shook his head. "Well, how can

I like to hear you shouting out bad language about my best friend?" A few

more words "on that line" and Willie was 'converted.' We heard no more

oaths from him except the mild ones, "By George,"by jing," or "by Golly,"

and in many an ingenious way thereafter he showed a sneaking fondness for

the Secretary. We

rested to-day for dinner on a hillock beside two deep pools of water, and

the Doctor made us some capital soup from preserved tomatoes and mutton.

Ten or eleven miles from our dining table brought us to the end of this

section of wooded country, where we had intended to camp for the night,

but the ponds were empty and no halt could be made. We therefore pushed on

across a vast treeless plain, twenty miles wide, with the knowledge that

if there was no water in a marsh beside a solitary tree four miles ahead,

we would have to go off the road for five miles to get some, and, as the

sun was setting, the prospect for the first time looked a little gloomy.

Making rapidly for the lonely tree, enough water for ourselves and horses

was found, and with hurrahs from the united party, the tents were pitched.

Forty-two and a half miles, the odometer shewed to be our day's travel.

August 10th.—The night of the 8th having been

so cold, we divided out more blankets the following evening by dispensing

with one tent, and sleeping three, instead of two, in each. The precaution

turned out to be unnecessary, though we kept it up afterwards for the

nights were always cool. This feature of cool nights after hot days is an

agreeable surprise to those who know how different it is in inland

countries, or wherever there is no sea breeze. It is one of the causes of

the healthy appearance of the new settlers even in the summer months. In

the hottest season of the year the nights are cool on these prairies and

the dews abundant, except when the sky is covered with clouds, and then

there is usually rain. No wonder that the grass keeps green when elsewhere

it is dry and grey.

Our morning's ride was across sixteen miles of the great plain, four miles

from the easterly edge of which we had camped. The Secretary walked the

distance, and got into the breakfast-place ten minutes after the mounted

party. A morning's walk or ride across such an open has a wonderfully

exhilarating effect. The air is so pure that it acts as a perpetual gentle

stimulant, and so bracing that little fatigue is felt, even after unusual

exertion; seldom is a hair turned on either horse or man.

The plain was not an unbroken expanse but a

succession of very shallow basins, enclosed in one large basin, itself

shallow, from the run of which you could look across the whole, whereas,

at the bottom of one of the smaller basins, the horizon was exceedingly

limited. No sound broke the stillness except the chirp of the gopher, or

prairie squirrel, running to his hole in the ground. The character of the

soil every few yards could be seen from the fresh earth, that the moles

had scarcely finished throwing up. It varied from the richest of black

peaty loam, crumbled as if it had been worked by a gardener's hand for his

pots, to a very light sandy soil. The ridges of the basins were often

gravelly. Everywhere the pasturage was excellent, though it was tall

enough for hay only in the depressions or marshy spots.

Our two next stages carried us over

twenty-five miles of a lovely country, known as the Little Touchwood

Hills; aspens were grouped on gentle slopes, or so thrown in at the right

points of valley and plain, as to convey the idea of distance and every

other effect that a landscape gardener could desire. Lakelets and pools,

fringed with willows, glistened out at almost every turn of the

road—though many of them were saline. Only the manorhouses and some

gently-flowing streams were wanting, to make out a resemblance to the most

beautiful parts of England. For generations, all this boundless extent of

beauty and wealth had been here, owned by England ; and yet statesmen had

been puzzling their heads over the "Condition of England's Poor, the Irish

Famine, the Land and Labor Questions," without once turning their eyes to

a land that offered a practical solution to them all. And the beauty in

former years had been still greater, for, though the fires have somehow

been kept oft this district for a few years, it is not very long since

both hardwood and evergreens as well as willows and aspens, grew all over

it; and then, at every season of the year, it must have been beautiful. It

is only of late years that fires have been frequent; and they are so

disastrous to the whole of our North-west that energetic action should be

taken to prevent them. Formerly, when the Hudson's Bay Company was the

only power in this "Great Lone Land," it was alive to the necessity of

this, and very successful in impressing its views on the Indians as well

as on its own servants. Each of its travelling parties carried a spade

with which the piece of ground on which the fire was to be made was dug

up, and as the party moved off, earth thrown on the embers extinguished

them. But since miners, traders, tourists and others have entered the

country, there has been a very different state of affairs. Some of the

spring traders set fire to the grass round their camps, that it may grow

up the better and be fresh on their return in autumn. The destruction of

forests, the drying up of pools, and the extermination of game by roasting

the spring eggs, are all nothing compared to a little selfish advantage.

And the Indians and the Hudson's Bay parties seeing this, have become

nearly as reckless.

This afternoon we had some idea of the lovely aspect that this country

would soon assume, if protected from the fire-demon. The trees grow up

with great rapidity; in five or six years the aspens are thick enough for

fencing purposes. There was good sport near the lake, and clumps of trees,

and Frank shot prairie-hen, partridge and teal, for dinner and next day's

breakfast. As he was confined to the roadside, and had no dog, he had but

indifferent chances for a good bag. We had to push on to do our forty-one

miles, and could not wait for sportsmen. At sunset the camp was selected,

by a pond in the middle of a plain, away from the bush so as to avoid

mosquitoes; and as Emilien was tired enough by this time, he agreed

readily to the proposal to rest on the following day.

August 11th.—Breakfast at 9 a. m., having

allowed ourselves the luxury of a long sleep on the "Day of Rest." The

water beside our camp was hard and brackish, scarcely drinkable in fact,

and not good even to wash with. It gave an unpleasant taste to the tea,

and even a dash of spirits did not neutralize its brackishness. Here again

the necessity of finding out the real state of the water-supply to this

country, was forced on our attention. Even if the pools do not all dry up,

the water in them at this time of the year is only what is left of melted

snow and the spring and summer rains, tainted with decayed vegetable

matter, and filled with animalculae. The question must be satisfactorily

settled; for men must have pure water and plenty of it.

This was a grand day for horses and men. Most

of the latter rose early and had their breakfasts and then went to sleep

again; others did not rise from under the carts and shake themselves out

of their buffalo blankets, till after ten o'clock. At 11.15 all assembled

for service—Roman Catholics, Methodists, Episcopalians and Presbyterians.

The Secretary sat on a box in front of the tents, with Frank by his side

holding an umbrella over both heads, as the sun shone fiercely. The

congregation, thirteen in number, sat in the doors, or shade of the tents.

Mr. McDougal led the responses, and all joined in devoutly. After the

service had been read and hymns sung, a short sermon was preached.

The advantages of resting

on the Lord's Day, on such expeditions as this, and also of uniting in

some common form of worship, are very manifest. The physical rest is

needed by man and beast. All through the week there has been a rush; the

camp begins to be astir at three in the morning, and from that hour till

nine or ten at night, there is constant high pressure. At the halting

places, meals have to be cooked, baggage arranged and re-arranged, horses

looked to, harness mended, clothes washed or dried, and everything kept

clean and trim; rest is therefore impossible. From four to six hours of

sleep are all that can be snatched. The excitement keeps a mere tourist

up, so that on Saturday night he feels quite able to go ahead, but if he

insists on pushing on, the strain soon becomes too much, and he loses all

the benefit to his health that he had gained: and to the men there is none

of the excitement of novelty, and they therefore need the periodic rest

all the more. But the

great advantages of the day, to such a party, are lost if each man is left

the whole time to look after himself,—as if there was no common bond of

union,—to sleep, to gamble, to ramble, to shoot, to snare gophers, to read

or write, and eat. Let the head of the party ask them to meet for

common-prayer or some simple service, let it be ever so short; all will

come if they believe that they are welcome. The singing of a hymn will

bring them round the tent or hillock where the service is held ; and the

kneeling together, the alternate reading, a few earnest kindly words, will

do more than anything else to awaken old remembrances, to stir the better

nature of all, to heal up little bitternesses, and give each that

sentiment or common brotherhood that cements into one the whole party.

The large body of Canadians that preceded

Milton and Cheadle in their journey across these same plains ten years

ago, would hardly have held together, had it not been for their observance

of the Sunday rest. In an account of their arduous expedition by this

route to the Cariboo gold mines, one of themselves gives the following

earnestly-worded testimony:— "The fatigues of the journey were now

beginning to have an injurious effect upon our animals, as well as upon

the tempers and dispositions of the men, and especially towards the end of

the week were these effects more apparent, when frequent disagreements and

petty disputes or quarrels of a more serious kind would take place, when

each was ready to contradict the other, and, at the slightest occasion or

without any occasion, to take offence. But to-morrow would be the Sabbath;

and no wonder that its approach should be regarded with pleasurable

anticipations, as furnishing an opportunity for restoring the exhausted

energies of both man and beast, for smoothing down the asperities of our

natures, and by allowing us time for reflection, for regaining a just

opinion of our duties towards one another ; and the vigor with which our

journey would be prosecuted, and the cordiality and good feeling that

characterized our intercourse after our accustomed rest on the first day

of the week, are sufficient evidence to us that the law of the Sabbath is

of physical as well as moral obligation, and that its precepts cannot be

violated with impunity. We certainly have had much reason gratefully to

adore that infinite wisdom and goodness that provided for us such a

rest."—All which we endorse as the utterances of sound common sense.

Our Sunday dinner was a good one. Terry had

time and did his best. Soup made from canned tomatoes and canned meat

gladdened our hearts. The Chief gave a little whiskey to the men, to take

the bad taste from the water and kill the animalculae; and Emilien took as

kindly to resting as if he had never travelled on Sundays in his life.

The afternoon was sultry and thundery. Heavy

showers, we could see, were falling ahead and all around, but, although

the clouds threatened serious things, we got only a sprinkling, and the

evening cleared up with a glorious sunset.

After tea, Mr. McDougal led our "family

worship." We did not ask the men to come, but the sound of the hymn

brought them round, and they joined in the short service with devoutness,

Willie, who had done a good day's work in snaring fat gophers, being

particularly attentive. They were all thankful for the rest of the day.

August 12th.—"The 12th" found us up early, as

if near a highland moor, and away from camp a few minutes after sunrise.

Another delightful day; sunny and breezy. First stage, thirteen miles; the

second, sixteen, and the third, fourteen miles, or forty-three for the

day; every mile across a country of unequalled beauty and fertility ; of

swelling uplands enclosing in their hollows lakelets, the homes of snipe,

plover and duck, fringed with tall reeds, and surrounded with a belt of

soft woods; long reaches of rich lowlands, with hillsides spreading gently

away from them, on which we were always imagining the houses of the

owners; avenues of whispering trees through which we rode on, without ever

coming to lodge or gate.

Our first "spell" [The term "spell" is

commonly used, all over the plains, to indicate the length of journey

between meals or stopping-places; the latter are sometimes called

spelling-places, by half-breeds and others.] was through the most

beautiful country, beautiful simply because longest spared by fire. Many

of the aspens were from one to two feet in diameter. Most of the water was

fresh, but probably not very healthy, for the lakes or ponds were shallow,

and the water tainted by the annual deposition of an enormous quantity of

decomposed organic matter. In summer when the water is low, it is

difficult to get at it, because of the depth of the mire. When the buffalo

ranged through this country and came to ponds to drink, they often sank so

deep in the mud that they were unable to extricate themselves, especially

if the foremost were driven on by those behind, or the hunters were

pressing them. The harder the poor beasts struggled, the deeper they sank;

till, resigning themselves to the inevitable, they have been known to

disappear from sight and be trampled over by others of the herd. The old

deeply indented trails of the herd, in the direction of the saline lakes,

are still visible. They used to lick greedily the saline incrustations

round the border, as they do still when near such lakes, Like domestic

cattle, they instinctively understand the medicinal value of salt. From

this point of view, it is doubtful if the saline lakes will prove a

serious disadvantage to the stock-raising farmer. In British Columbia and

on the Pacific Coast generally, such lakes are found, and the cattle that

are accustomed to the water. receive no injury from drinking it.

On our way to dinner, two large white cranes

rose swan-like from a wet marsh near the road. Frank with his gun and

Willie with a stone made after them. The larger of the two flew high, but

Willie's stone brought down the other. As he was seizing it, the big one,

evidently the mother, attacked him, but, seeing the gun coming, flew up in

time to save herself. The young one was a beautiful bird, the extended

wings measuring over six feet from tip to tip. As soon as Willie had

killed his game, he rode off in triumph with it slung across his

shoulders. In twenty minutes after his arrival at camp, he and his mates

had plucked, cooked, and disposed of it, all uniting in pronouncing the

meat delicate and 'first-class.'

After dinner a good chance of killing a brown"

bear was lost. At a turn of the road he was surprised on a hillock, not

twenty yards distant from the buckboard that led our cavalcade. Had the

horsemen and guns been in front as usual, he could have been shot at once;

but, before they came up, he was off, at a shambling but rapid gait among

the thickets, and there was not time to give chase. This was a

disappointment, for all of us would have relished a bear-steak.

The low line of the

Touchwood Hills had been visible in the forenoon; and, for the rest of the

day's journey, we first skirted them in a north-westerly direction, and

then, turning directly west, we gained their height by a road so winding

and an ascent so easy, that there was no point at which we could look back

and get an extended view of the ground travelled in the course of the

afternoon. It is almost inaccurate to call this section of country by the

name of "Hills," little or big. It is simply a series of prairie uplands,

from fifty to eighty miles wide, that swell up in beautiful undulations

from the level prairies on each side. They have no decided summits from

which the ascent and the plain beyond can be seen; but everywhere are

grassy or wooded, rounded knolls, enclosing natural fields or farms, with

small ponds in the windings and larger ones in the lowest hollows. The

land everywhere is of the richest loam. Every acre that we saw might be

ploughed. Though not as well suited for steam ploughs as the open prairie,

in many respects this section is better adapted for farming purposes,

being well wooded, well watered, and with excellent and natural drainage,

not to speak of its wonderful beauty. All that it lacks is a murmuring

brook or brawling burn; but there is not one, partly because the trail is

along the watershed. On a parallel road farther north that passes by Quill

Lake, Mr. McDougal says that there are running streams, and that the

country is, of course, all the more beautiful.

Our camp for the night was beside two lakelets

near forks where the road divides, one going northerly from our course to

the old Touchwood trading-post, fifteen miles distant.

So passed 'the 12th' with us. If we had not

sweet-scented heather and Scotch grouse, we had duck and plover and

prairie hen ; and, beside the cheery camp-fires under a cloudless

star-lit-sky, we enjoyed our feast as heartily as any band of gypsies or

sportsmen on the moors.

August 13th.—Heavy rain this morning which

ceased at sunrise. Got off an hour after, and descended, in our first

stage of fourteen and a half miles, the western side of the Touchwood

Hills. This side is very much like the other; the descent to us was so

imperceptible that nowhere could we see far ahead or feel certain that we

were descending, until the most western upland was reached, and then,

beneath and far before us, stretched a seemingly endless sea of level

prairie, a mist on the horizon giving it still more the look of a sea.

Early in the morning we came upon two buffalo-tents by the roadside. In

these were the first Indians we had fallen in with since meeting the Sioux

at Rat Creek, with the exception of two or three tents at "the crossing"

of the Assiniboine. They were two families of Bungys, (a section of the

Salteaux or Ojibbeway tribe) who had been hunting buffalo on the prairie

to the south-west of us.. They had a good many skins on their carts, and

the women were engaged at the door of a tent chopping up the fat and meat

to make pemmican. Marchaud, our guide, at once struck "a trade" with them,

a few handfuls of tea for several pieces of dried buffalo meat. The men

seemed willing that he should take as much as he liked, but the oldest

squaw haggled pertinaciously over each piece, and chuckled and grinned

horribly when she succeeded in snatching away from him the last piece he

was carrying off. She was the only ugly being in their camp. The men had

straight delicate features, with little appearance of manly strength in

their limbs; hair nicely trimmed and plaited. Two or three young girls

were decidedly pretty, and so were the little pappooses. The whole party

would have been taken for good looking gypsies in England.

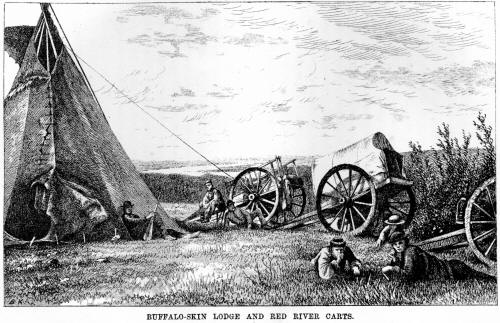

The road on this stage was the worst we had

travelled over; so full of ruts and boulders that the axle of one of the

carts snapped, and as there was not time to make another, the cart had to

be abandoned by the road-side till Emilien's return from Carlton. It was a

marvel how well those Red River carts stood out all the jolting they got.

When any part broke before, a thong of Shaganappi had united the pieces.

Shaganappi in this part of the world does all that leather, cloth, rope,

nails, glue, straps, cord, tape, and a number of other articles are used

for elsewhere. Without it the Red River cart, which is simply a clumsy

looking, but really light, box cart with wheels six or seven feet in

diameter, and not a bit of iron about the whole concern, would be an

impossibility. These high wheeled carts cross the miry creeks, borne up by

the grass roots, when ordinary waggons would sink to the hubs.

After breakfast we entered on a vast plain

that stretched out on every side, but the one we had left, to the horizon.

This had once been a favourite resort of the buffalo, and we passed in the

course of the day more than a score of skulls that were bleaching on the

prairie. All the other bones had been of course chopped and boiled by the

Indian women for the oil in them. The Chief picked up two or three of the

best skulls to send as specimens to Ottawa. Great was "Souzie's" amazement

at such an act He had been amused at the Botanist gathering flowers and

grasses; but the idea of a great O-ghe-ma coming hundreds of miles, to

carry home bones without any marrow in them, was inexplicable. He went up

to Frank and explained by gestures that they were quite useless, and urged

him to throw them out of the buckboard, and when Frank shook his head he

appealed to Mr. McDougal to argue with us. All his efforts failing, he

gave it up; but whenever his eyes caught sight of the skulls it was too

much for even Indian gravity, and off he would go into fits of laughing at

the folly of the white men.

Our second "spell" was nineteen, and the

third, nine miles across this treeless desolate-looking prairie. Towards

evening the country became slightly broken and wooded, but we had to camp

on a spot where there was not enough wood to make the fires for the night.

Knowing this, Marchaud passed the word to the men on horseback, two or

three miles before arriving at the camp. They dashed into a thicket,

pitched some small dead dry wood into the carts, and then each throwing an

uprooted tree from fifteen to twenty-five feet long, and four to six

inches in diameter across his shoulders or on the pommel of his saddle,

cantered off with it, Sancho Panza like, as easily as if it was only a

long whip. They had done this several times before, Willie generally

picking out the biggest tree to carry, and, no matter how unwieldy the

load, they rode their horses firmly and gracefully as ever.

The prairie crossed to-day extends

north-easterly to Quill Lake, the largest of the salt lakes. Just on that

account, and because all the ponds on it are saline, clearly shown, even

where dried up, by the reddish samphire or white incrustations about the

edges, one or two test wells should be sunk here; for if good water is

found on this plain, it will likely be found everywhere.

To-day we had two opportunities of sending to

Red River letters or telegrams for home, and—lest one should fail—availed

ourselves of both. Tying our packets with red tape, to give them an

official look and thus impress Posty with due care, and sealing the

commission with a plug of tobacco, we trusted our venture with the

comfortable feeling that we had re-established our communications with the

outer world. [It is

only fair to mention that both messengers, one of them a French, the other

a Scotch half-breed and parishioner of Mr. McDougal's, proved trusty.

Every letter or telegram we sent from the plains reached home sooner than

we had counted on.]

All day our men had been on the outlook for

buffalo but without result. Marchaud rode in advance, gun slung across his

shoulders, but although he scanned every corner of the horizon eagerly,

and galloped ahead or on either side to any overhanging lip of the

plateau, no herd or solitary bull came within his view. They were not far

off, for fresh tracks were seen, few in comparison to the tracks of former

times, indented in the ground like old furrows and running in parallel

lines to the salt lakes, as if in those days the whole prairie had been

covered with wood, and the beasts had made their way through in long files

of thousands. August

14th.—The thermometer fell below freezing point last night, but the

additional allowance of blankets kept us warm enough. At sunrise there was

a slight skiff of ice on some water in a bucket; and, in the course of the

morning's ride, we noticed some of the leaves of the more tender plants

withered, but whether from the frost, or blight, or natural decay—they

having reached maturity,—we could not determine.

The sun rose clear, and the day like its

predecessors was warm and bracing, the perfection of weather for

travelling. We had hitherto been on "the height of land" that divides the

streams running into the Assiniboine from those that run into the Qu'

Appelle, and this, in part, accounts for the absence of creeks near our

road. To-day we got to a still higher elevation, the watershed of the

South Saskatchewan, and found, in consequence, that the grass and flowers

were in an advanced stage as compared with those farther east. The grass

was grey and ripe, and flowers, that were in bloom not far away, were

seeding here. The general upward slope of the plains between Red River and

Lake Winnepeg, and the Rocky Mountains, is towards the west. The elevation

at Fort Garry is 700 feet, at Fort Edmonton 2088 feet, and at the base of

the Mountain Chain 3000 feet above the sea. This rise of 2,300 feet is

spread over a thousand miles, but Captain Palliser marked three distinct

steppes in this great plain. The first springs from the southern shore of

the Lake of the Woods, and, trending to the south-west, crosses the Red

River well south of the boundary line; thence it runs irregularly, in a

north-westerly direction, by the Riding Mountains toward Swan River, and

thence to the Saskatchewan—where the north and south branches unite. The

average altitude of the easterly steppe is from 800 to 900 feet above the

sea level. The second or middle steppe, on which we now are, extends west

to the elbow of the South Saskatchewan, and thence northwards to the Eagle

Hills, west of Fort Carlton. Its mean altitude is 1600 feet. The third

prairie steppe extends to the mountains. Each of these steppes, says

Palliser, is marked by important changes in the composition of the soil,

and consequently in the character of the vegetation.

Our first "spell" to-day was fifteen, and our

second, twenty miles, to "the Round Hill," over rolling or slightly broken

prairie; the loam was not so rich as usual and had a sandy subsoil. Ridges

and hillocks of gravel intersected or broke the general level, so that,

should the railway come in this direction, abundant material for

ballasting can be promised.

The prairie to-day had an upward slope till

about one o'clock, when it terminated in a range of grassy round hills.

For the next hour's travelling the road wound through these; a succession

of knolls enclosing cup-like basins, which in the heart of the range

contained water, either fresh or saline. Wood also began to re-appear;

and, when we halted for dinner, at the height of the range, the beauty

that wood, water, and bold hill-sides give were blended in one spot. We

were certainly three or four hundred feet above the prairie ; the scenery

round us was bolder than is to be found in any part of Ontario, and

resembled that of the Pentlands, near Edinburgh. It is well to mention

this, because of the exaggerated ideas that some people have when a

country is spoken of. The hill at the foot of which we camped rose

abruptly from the rest, like the site of an ancient fortalice. Horetski

described it as a New Zealand pah; one hill, like a wall, enclosing

another in its centre, and a deep precipitous valley, that would have

served admirably as a moat, filled with thick wood and underbrush, between

the two. Climbing to the summit of the central hill, we found ourselves in

the middle of a circle, thirty to forty miles in diameter, enclosing about

a thousand square miles of beautiful country. North and east it was

undulating, studded with aspen groves and shining with lakes. To the south

and west was a level prairie, with a sky line of hills to the south-west.

To the north-west—our direction—a prairie fire, kindled probably by embers

that had been left carelessly behind at a camp, partly hid the view.

Masses of fiery smoke rose from the burning grass and willows, and if

there had been a strong wind, or the grass less green and damp, the beauty

of much of the fair scene we were gazing on would soon have vanished, and

a vast blackened surface alone been left.

It was nearly 4 P.M. before we left "the Round

Hill:" and then we passed between the remaining hills of the range, and

gradually descended to the more level prairie beyond, through a beautiful,

boldly irregular country, with more open expanses than the Touchwood Hills

showed, and more beautiful pools, though the wood was not so artistically

grouped. Passing near the fire, which was blazing fiercely along a line of

a quarter of a mile, we saw that it had commenced from a camping ground

near the roadside. Heavy clouds were gathering that would soon extinguish

the flames. As there was the appearance of a terrific thunder storm, we

hurried to a sheltered spot seven or eight miles from Round Hill, and

camped before sunset, just as heavy drops commenced to fall. The speed

with which our arrangements for the night were made astonished ourselves.

Every one did what he could ; and in five minutes the horses were

unharnessed, the tents pitched, the saddles and all perishable articles

covered with waterproofs; but, while exchanging congratulations, the dense

black clouds drove on to the south, and, though the sky was a-flame with

lightning, the rain scarcely touched us.

August 15th.—Early in the morning rain

pattered on our tents, but before day-light it had all passed off, and we

started comfortably at our usual hour, a little after sunrise. Our aim was

to reach the south branch of the Saskatchewan, forty-six miles away,

before night; the distance was divided into three 'spells' of thirteen,

seventeen, and sixteen miles.

The scenery in the morning's ride was a

continuation of that of last night ; through a lovely country, well

wooded, abounding in lakelets, swelling into softly-rounded knolls, and

occasionally opening out into a wide and fair landscape. The soil was of

the richest loam and the vegetation correspondingly luxuriant; the flora

the same, and almost at the same stage, as that we had first seen on the

prairie, a fortnight before, near Red River;—the roses just going out of

bloom; the yellow marigolds and golden-rods, the lilac bergamot, the white

tansey, blue-bells and harebells, and asters, of many colours and sizes,

in all their splendour. We were quite beyond the high and dry region ; and

again in a country that could easily be converted into an earthly

paradise. We met or

passed a great many teams and "brigades" to-day; traders going west, and

half-breeds returning east with carts well-laden with buffalo skins and

dried meat. A number of Red River people club together in the spring, and

go west to hunt the buffalo. Their united caravan is popularly called "a

brigade," and very picturesque is its appearance on the road or round the

camp-fire. The old men, the women and little children are all engaged on

the expedition, and all help. The men ride and the women drive the carts.

The children make the fires and do 'chores' for the women. The men shoot

buffalo ; the women dry the meat and make it into pemmican.

Our breakfast place was a neck of land between

two lakes, one of them sweet, the other bitter. The elevation of the two

seemed to be the same, but, on a closer look, the fresh lake was seen to

be the higher of the two, so that when full it would overflow into the

other. This was invariably the case, as* far as we saw, when two or more

of such lakes were near each other. The salt lakes had no outlet, the

natural drainage passing off only by absorption and evaporation.

The country between this first halt and the

Saskatchewan consisted of three successive basins; each bounded by a low

ridge, less or more broken. Everywhere the ground was uneven, not so well

suited as the level for steam agricultural implements, but the very

country for stock-raising or dairy farms. The road was bad, and no wonder,

according to the axiom that good soil makes bad roads. The ruts were deep

in black loam, and rough with willow roots. Even when the wheels sank to

the axles, they never brought up any clay; moist, dripping, black muck,

that would gladden the eyes of a farmer, was all that they found.

Soon after dinner, we came to the last ridge,

and before us spread out a magnificent panorama. Fifteen miles farther

west rolled the South Saskatchewan. We could not see the river, but the

blue plateau that formed our sky line was on the other side of it. And

those fifteen miles at our feet, stretching to an indefinite horizon on

the south, and bounded five miles away to the north by Minitchenass or

'the lumping hill of the woods,' showed every variety of rolling plain,

gentle upland, wooded knoll, and gleaming lake. Where hundreds of

homesteads shall yet be, there is not one. Perhaps it is not to be

regretted that there is so much good land in the world still unoccupied.

The intense saltness of many of the lakes was to us the only doubtful

feature in the landscape. One at our feet several miles long had a shore

of brightest red, sure sign of how it would taste. All at the foot of the

ridge with one exception are saline; after going on a few miles and

mounting a slope, they are fresh.

The sun set when we were still five miles from

the river. Another axle had broken and heavy clouds threatened instant

rain. Some advised halting; but the desire to see the Saskatchewan was too

strong to be resisted, and we pushed on at a rattling rate over the rutty

and uneven road. Never were buckboards tested more severely, and no carts

but those of Red River could have stood for ten minutes the bumps from

hillock to hillock, over boulders, roots, and holes, at a break-neck rate.

The last mile was down hill. The Doctor and the Chief dashed on at a

gallop, and only drew rein when, right beneath, they saw the shining

waters of the river. The rest of us were scarcely a minute behind, and

three rousing cheers sent back the news to the carts. In twelve working

days, we had travelled five hundred and six miles, doing on this last

forty-six; and the horses looked as fresh as at the beginning of the

journey; a fact that establishes the nutritious properties of the grasses

that were their only food on the way, as well as the strength and the

hardihood of the breed.

The first thing the Chief saw to, after

pitching the tents, was the preparation of a kettle of whiskey-toddy, of

which all who were not teetotallers received an equal share. The allowance

was not excessive after nearly a fortnight's work; about three half-pints

to thirteen men, six of them old voyageurs; but they had been so

abstemious on the road that it was quite enough, and great was the

hilarity with which each one drank his mug-full, pledging the Queen,

sweethearts and wives, the Dominion, and the Chief. It shakes a company

together to share something in common occasionally; and by this time we

felt a personal interest in every member of the party, and looked forward

with regret to the farewells that would be exchanged to-morrow.

While at supper rain began to fall, and it

continued with intermissions all night, but we slept soundly in our

tents,—caring nothing, for were we not faring on in good style? A month

from Toronto and we were on the Saskatchewan.

August 16th.—The morning was grey and chilly,

and there was some delay in getting the scow, that is now kept on the

river by the Hudson's Bay Company, up from a point where it had been left,

so that we did not move from camp till 8 o'clock. This delay gave the

Botanist an hour or two to hunt for new species, which he did with all

diligence, and the rest of us had time for a swim or a ramble up and down

the river. Our Botanist had been slightly cast down of late by finding few

new varieties. The flora of the five hundred and thirty miles between the

eastern verge of the prairie at Oak Point, and the Saskatchewan, is

wonderfully uniform. The characteristic flowers and grasses are everywhere

the same. We expect, however, to meet with many strange varieties after

crossing the two Saskatchewans.

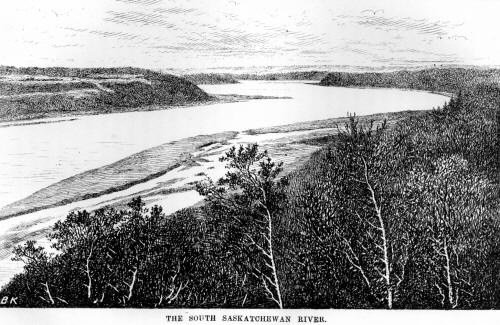

At this point of the river, where the scow is

usually kept and where a regular ferry is to be established next year,

crossing is an easy matter. When there was no scow, every party that came

along had to make a raft for their baggage, and a whole day was lost. Our

buckboards, carts, and Mr. McDougal's waggons made two scow-loads ; and

the horses swam across. Some were very reluctant to go into the water, but

they were forced on by the men, who waded after them—shouting and throwing

stones,—to the very brink of the channel. Once in there, they had to swim.

Some,—ignorant of "how to do it"— struggled violently against the full

force of the current or to get back, when of course they were stoned in

again. Others went quietly and cunningly with the current and got across

at the very point the scow made. The river for a few minutes looked alive

with horses' heads, for that was all that was seen of them from the shore.

As the water was lower and the force of the stream less than usual, all

got across with comparative ease. The river at this point is from two

hundred to two hundred and fifty yards wide. A hand-level showed the west

bank to be about a hundred and seventy feet high, and the east somewhat

higher. Groves of aspens, balsams, poplars, and small white birch are on

both banks. The valley is about a mile wide, narrower therefore than the

valley of the Assiniboine or the Qu'Appelle, though the Saskatchewan is

larger than the two put together. The water now is of a milky grey colour,

but very sweet to the taste, especially to those who had not drunk of

'living water' for some days. A month hence it will be clear as crystal.

In the spring it is discoloured by the turbid torrents along its banks,

composed of the melting snows and an admixture of soil and sand ; and this

colour is continued through the summer, by the melted snow and ice and the

debris borne along with them from the Rocky Mountains. In August it begins

to get clear, and remains so till frozen, which usually happens about the

end of November. Near

the ferry an extensive reserve of land has been secured for a French

half-breed settlement. A number of families have already come up from Fort

Garry. We did not see them as the buffalo-magnet had drawn them away to

the plains. The scantling for a house was on the ground near our camp.

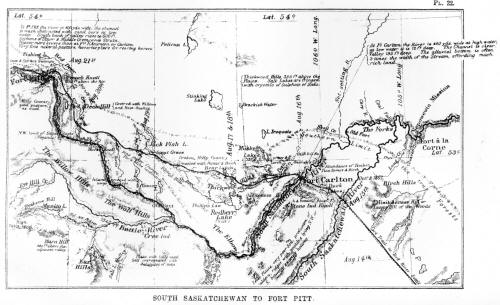

After crossing, most of us drove rapidly to

Fort Carlton,— eighteen miles distant, on the North Saskatchewan,—being

anxious to see a house, store, and civilized ways and people again. Mr.

Clark, the agent, received us with customary Hudson's Bay hospitality. The

eighteen miles between the two rivers is a plateau, not more at its

highest than three hundred feet above either stream. The soil looked

rather light and sandy, but sufficiently rich for profitable farming.

There is capital duck-shooting on lakes near the road. From the ancient

bank of the river, above the Fort, is a good view of the course of the

north stream. It is a noble river, rather broader, with higher banks and a

wider valley, than the south branch. The usual square of four or five

wooden buildings, surrounded by a high plank fence, constitutes "the

Fort," and, having been intended for defence against Indians only, it is

of little consequence that it is built on the low ground, so immediately

under the ancient bank of the river that you can look down into the

inclosure, and almost throw a stone into it from a point on the bank.

Fifty miles down stream is the Prince Albert Presbyterian Mission to the

Crees, where there is also the nucleus of a thriving Scotch settlement.

Fifty miles farther down, in the same north-easterly direction, the two

Saskatchewans unite, and then pursue their way with a magnificent volume

of water—broken only by one rapid of any consequence—to Lake Winnipeg.

We dined with Mr. Clark on pemmican, a strong

but savoury dish, not at all like 'the dried chips and tallow' some

Sybarites have called it. There is pemmican and pemmican however, and we

were warned that what is made for ordinary fare needs all the sauce that

hunger supplies to make it palatable.

A few hours before our arrival, Mr. Clark had

received intelligence from Edmonton, that Yankee free-traders from Belly

River had entered the country, and were selling rum to the Indians in

exchange for their horses. The worst consequences were feared, as when the

Indians have no horses they cannot hunt. When they cannot hunt, they are

not ashamed to steal, and stealing leads to wars. The Crees and Blackfeet

had been at peace for the last two or three years, but, if the peace was

once broken, the old thirst for scalps would revive and the country be

rendered insecure. Mr. Clark spoke bitterly of the helplessness of the

authorities, in consequence of having had no force from the outset to back

up the proclamations that had been issued. Both traders and Indians were

learning the dangerous lesson that the Queen's orders could be disregarded

with impunity; and it would cost more before the lesson was unlearned,

than would have taught the opposite at the beginning of the new regime. We

comforted our good host with the assurance that the Adjutant-General was

coming up with thirty men, to repress all disorders and to see what was

necessary to be done for the future peace of the country.

Making all allowances for the fears of those

who see no protection for life or property within five hundred or a

thousand miles of them, and for the exaggerated size to which rumours

swell in a country of such magnificent distances, where there are no

newspapers and no means of communication except 'expresses,' it is clear

that if the government wishes to avoid worrying, expensive, murderous

difficulties with the Indians, 'something must be done.' There must be law

and order all over our North-west from the first. Three or four companies

of fifty men each, like those now in Manitoba, would be sufficient for the

purpose, if judiciously stationed. Ten times the number may be required if

there is long delay. The country cannot afford repetitions of the Manitoba

rebellion, on account of the neglect of either half-breeds or Indians. The

Crees are anxious for a treaty. The Blackfeet should be dealt with firmly

and generously; treaties made with both on the basis of those agreed upon

in the east; a few simple laws for the protection of life and property

explained to them, and their observance enforced; small annuities allowed;

the spirit-traffic prohibited, and schools and missionaries encouraged.

On asking Mr. Clark why there was no farm at

Carlton, he explained that the neighbourhood of a fort was the worst

possible place for farm or garden ; that the Indians who come about a fort

from all quarters, to trade and to see what they can get, would, without

the slightest intention of stealing, use the fences for firewood, dig up

the potatoes and turnips, and let their horses get into the grain-fields.

He had therefore established a farm at the Prince Albert Mission, fifty

miles down the river.

With regards to crops, barley and potatoes

were always sure, wheat generally a success, though threatened by frosts

or early drought, and never a total failure. This year, he expected two

thousand bushels of wheat from a sowing of a hundred. The land at Carlton,

and everywhere round, is the same as at Prince Albert. Its only fault is

that it is rather too rich.

After dinner, three or four hours were allowed

for writing letters home, and making arrangements for the journey farther

west. We got some fresh horses and provisions from Mr. Clark; said

good-bye to Emilien, Marchand, Willie, Frederick, and Jerome ; and taking

two of our old crew, Terry and Maxime, along with two half-breeds and a

hunch-backed Indian from Carlton, crossed the North Saskatchewan before

sunset. In addition to Mr. McDougal, two Hudson's Bay officers joined

us—one of whom, Mr. Macaulay, had been long stationed at Jasper House and

Edmonton, and the other, Mr. King, far north on the McKenzie River. The

scow took everything across in two loads, and the horses swam the river;

but it was after dark before the tents were pitched on the top of the

hill, and nearly midnight when we got to bed.

|