|

I WAS ONE of a number of

engineers who joined in ushering in the New Year by a celebration at

Foster's winter quarters, on the left bank of the Beaver River. This took

the form of a midnight supper, in which — including rodmen and chainmen —

some twelve or more took part.

To provide the liquid

refreshment for this party, each engineer brought a bottle with him,

containing either whisky or rum, or some other concoction — all most

likely of questionable quality. But whatever the quality, it got well

concealed in a brew which Foster set about making, as each one on his

arrival handed him his bottle.

I can yet see his amused

smile, as he proceeded to decant the contents of the bottles which Stuart

and I brought, into a large tin basin, bottomed well with hot water and

lemon.

It was as a cocktail before

supper that we sampled this potent mixture — which might aptly be called

the "Foster Cocktail". Each one ladled his own, with a tin cup, from the

ample supply in the reservoir.

Foster and his rodman Hill

were excellent hosts. At supper, Foster as chairman and toastmaster,

proposed a toast to each of the countries represented at that gathering:

Canada, United States, England, Scotland, Wales, India, and Australia.

Some of these had more than one representative.

I was the sole Scot. Foster

was a Canadian; Hill an American. The toasts to India and Australia were

each responded to by an Englishman; India by Stuart, who was born there;

Australia by Stoess, who had been engaged in engineering there before

coming to Canada. I am uncertain about the others.

In responding to the toast

to India, Stuart emphatically expressed his objection to the implication

underlying that toast, that because he happened to have been born in

India, he must necessarily be an Indian. Stoess, on the other hand, made

no demur at being called an Australian. He was just, he admitted — to use

his own expression — an "a-bory-jine from the anti-poads". And that name

stuck to him.

Everyone in turn had a

toast to reply to. No one, however, distinguished himself by his oratory.

Speech-making was not their strong point. Moreover, each speaker, trying

his hardest to say something brilliant, had to run the gauntlet of

good-natured chaff from the others. But that gave us all the more fun.

This party may well be said

to have been unique. For, here was a gathering of young men who, but a

short time before, did not even know of each other's existence. Now, they

were just like members of one large family, co-operating loyally with each

other in the part assigned them in the building of the railway.

So, when the party broke up in the early hours of the morning, it was with

a rousing cheer, and a hearty "Hurrah for the C.P.R."

The location of the railway

in the Selkirks up Roger's Pass to the summit, presented an aspect in

striking contrast to that of the location from the Kicking Horse Flats to

Beavermouth. The railway in that section, as already shown, kept close to

the river, crossing and re-crossing it, wherever necessary to get the most

economical location; and the tote-road, in general, rose high above it —

particularly at the Golden Stairs. But in the Selkirks, it was the railway

that, after having once crossed the Beaver River, rose above both it and

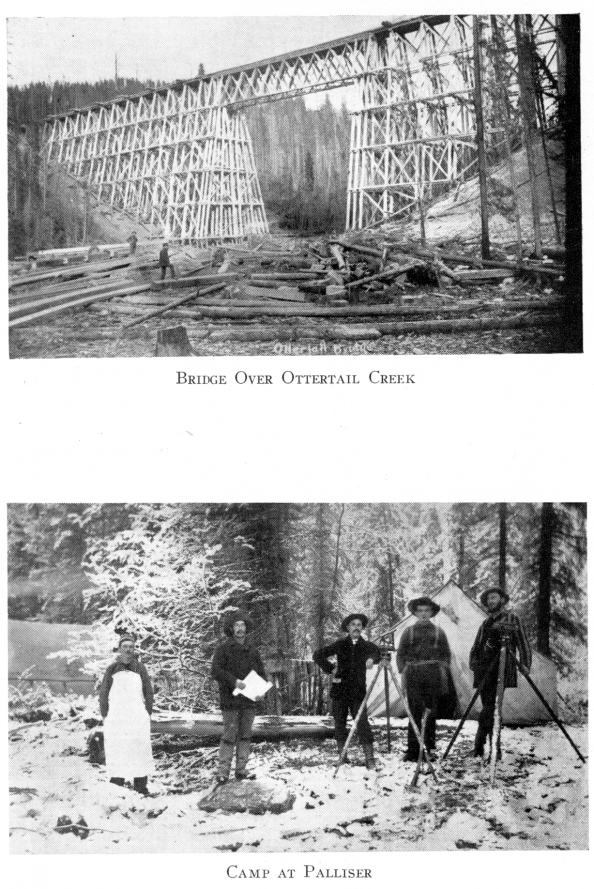

the tote-road; in some places as high as from 200 to 300 feet.

In thus climbing the

Selkirks, the railway had to cross a number of deep gulches cut in the

mountain side by tributaries of the Beaver; and it was over these gulches

that the largest and highest bridges were required. As these bridges were

situated widely apart, and were all to be built during the winter about

the same time, it was not practicable for one engineer to look after them

all. So this work was apportioned among three.

On my section, in addition

to the bridges over Mountain Creek and Cedar Creek, I had a number of

smaller ones — including the one over the Beaver. Stoess had charge of the

bridge over Surprise Creek and Swan the one over Stoney Creek, some 300

feet high — the highest of all.

Close to the railway bridge

over the Beaver, there was another bridge of an entirely different type.

It was a pack-trail bridge consisting simply of three logs pinned

together, and spanning a narrow gorge of the river. Over it the

pack-horses of the locating engineers had crossed back and forth when the

line was being located. Although no longer in use, this unique relic was

then still existing; and I made a sketch of it which I added to my

collection.

The log house which served

as my winter camp was situated between Mountain Creek and Cedar Creek, and

was close to the tote-road. It served its purpose well, for we passed the

winter in it most comfortably. Ellison, too, appreciated it for he became

a frequent visitor, and often stayed overnight.

Mountain Creek bridge was

1,200 feet long and 150 feet high. It was the largest of all the bridges

in regard to the amount of timber required to build it. It consisted of a

central span of 150 feet, flanked at each end by two smaller truss spans

of 30 feet each; and by a number of trestle and pile bents 15 feet apart.

On the approaches at each end, the ground was of gentle slope; so there

was no difficulty in laying out this work.

But it was quite a

different story at Cedar Creek. Although this was a much smaller bridge —

one span of 100 feet, and 100 feet high — the approaches were steep rocky

cliffs, and the laying out of the work involved the use of a rope in

climbing these cliffs. On one occasion Stuart and I were standing on a

ledge clinging to the rope, when a big chunk of hardened snow thundered

down on top of us. It knocked us off our perch and sent us sliding down

the rope at lightning speed to the ground below.

One bright, sunny day when

I was returning by myself to camp from Cedar Creek, I witnessed a peculiar

phenomenon. As I walked along, the leaves on the trees suddenly took on a

most unnatural hue; and there was a stillness in the air which gave me a

feeling of awe. I was at a loss to account for this phenomenon until I

looked up at the sun, and saw that it was undergoing an eclipse; a partial

one, it turned out to be.

I was quite unaware that an

eclipse was to take place that day; so I may rightly claim to have

discovered it by myself.

Two events of more than

local interest took place in the spring that year.

One was a strike of the

workmen which had far-reaching effects. Although this was called a strike,

it was not a strike in the ordinary meaning of that word. The men did not

strike for higher wages, nor for better conditions of living. They simply

struck for payment of wages they had earned, which were long overdue. This

revealed the critical financial position to which the railway company had

been reduced.

The men were unpaid because

the company did not have the money to pay the contractors; and the

contractors consequently couldn't pay the men the wages which were due to

them.

The men quit work at the

camp at the farthest outpost of the section of the railway then under

construction; and set out on a march to the End of Track, then near

Beavermouth. On the way, they gathered to their cause the men in the

camps, of the other contractors. So, by the time they reached Mountain

Creek, they formed an imposing body.

Track-laying, which had

been suspended for the winter, was about to be started again, and the

carpenters were busy at work on the top of the bridge, in an effort to get

it completed by the time the track reached that point. The strikers were

massed on the ground below; and they called on the carpenters to stop work

and come down off the bridge. But this the carpenters refused to do. They

were in no way minded to join in the strike.

One of the strikers,

however, hit on a way to compel them to stop work. I saw him take an axe

and cut the rope in the block-and-tackle arrangement by which material was

being hoisted. Down dropped the load with a crash. So, for lack of

material the carpenters could do no work. They still, however, remained on

the bridge.

R. Balfour, manager for

Mackenzie, the bridge contractor, was standing beside me at the time, and

he asked me to come with him to his office and talk over what should be

done. I went with him; but we had no time to discuss the situation before

the strikers came milling around. Their spokesman evidently didn't

particularly like his job, for the crowd kept pushing him toward us.

Finally, he faced us as we were standing outside the office. There was a

moment of tense silence which he broke by stating in no uncertain terms,

that he wanted it understood that there was to be no work done on the

bridge until the men got paid. Balfour replied that that might be all very

well for them; but the contractor, he said, was liable to a heavy penalty

if he delayed the track-laying. "You stop work on the bridge," the

spokesman shot back, "and we'll look after the track." There was nothing

more to be said, so Balfour yielded and called the carpenters off the

bridge.

The strikers continued

their march to Beavermouth where, according to all accounts, they had a

wild time. It required the utmost efforts of the Mounted Police under

Major Steele — ably supported by Sergeant Fury — to restore order. George

Hope Johnston, then a British Columbia Police Magistrate, read the Riot

Act. He was afterwards a well-known citizen of Calgary.

But the strike, after all,

was to the advantage of the railway company. It brought to the attention

of the Dominion Government, beyond any doubt, the serious plight of the

company. Without assistance from the government the railway could not be

completed. And assistance to an extent which assured its completion was

promptly given. We learned shortly afterwards that a pay-car was on its

way with sufficient money to pay the legitimate claims of the men. But

this news did not make them return to work immediately. They wanted their

pay first, and refused to work until they did get it.

I remember hearing one of

the contractors, Donald D. Mann — usually spoken of as Dan Mann — address

the men in an endeavour to get them to go back to work. He stressed the

fact that a pay-car was on its way, and that they would be paid as soon as

it arrived, but they stood by their guns. They were through with promises

It was their pay they wanted.

However, the pay-car did

turn up, and the men got paid, and they returned to work. Thus happily

ended the strike.

Then came the Riel

Rebellion. It did not affect, to any great extent, the work of

construction in the mountains. It did, however, much reduce the police

force; for the greater part of the men in this force — among whom was

Ralph Bell — left with Steele to take part in quelling the rebellion.

These men formed the

nucleus of what was afterwards known as Steele's Scouts, a body which won

recognition for its highly efficient and effective work.

After the defeat of Riel,

Steele and his men returned to the mountains, and resumed their police

duties as before.

When Mountain Creek bridge

was practically completed, Ross came along, and I accompanied him on the

bridge on his usual thorough inspection of the work. There were some

planks of the staging underneath the deck, still in place. Seeing these,

he wanted to get down to them to make some inspection there. To do this he

squeezed his body through the deck between the ties. But he could get no

further. He looked up to me and laughed; and said he couldn't get his head

through. It may seem odd that he could get his body through a space that

was too narrow for his head. But that was how he was built; a slim body,

but a large head.

There were no great

difficulties encountered in the location of the railway to the summit, in

the Selkirks. But getting down on the western slope was a problem which

Sykes, with a party in the field, had for some time been endeavouring to

solve. And he succeeded. He located a line which came to be known as the

Loop.

I do not know what Sykes'

full initials were, but I have a recollection of having heard him called

"Sammy Sykes".

This line consisted of a

series of loops winding back and forth across a number of streams, until

it had got down to, practically, the level of the Illicilliwaet River.

It was to the Loop that I

made my next move. This move meant abandoning our comfortable log house,

and getting back into tents. But that didn't trouble us in the least. It

was all in our job.

There were five bridges —

mostly fairly high trestles — comprised in this series of loops. One was

near to Glacier over Glacier Creek, a tributary of the Illicilliwaet. Two

were over another tributary, Ross Creek; and two were over the

Illicilliwaet. Most of these bridges were on curves.

The scenery as viewed from

our camp, at the lower end of the Loop, appealed to me to make some

sketches. The mountains too, towering above, called on us to climb them.

So, one Sunday, Stuart and

I set out to climb the one which was closest to our camp. It was a hard

climb, as a great part of the way was through burned fallen timber. But we

got to the top, and were glad to sit down there and rest, and eat our

lunches consisting of some sandwiches which we had carried in our pockets.

When so engaged, I started to read the piece of newspaper in which my

lunch had been wrapped. The first sentence which caught my eye was to this

effect: "If you want a real good glass of beer, go to So-and-So's bar". I

could well have enjoyed a good glass of beer; but the bar, alas, was far

away.

Descending was even harder

than the climb had been; for we took a short cut which led us through a

more entangled part of the fallen timber. Thus we arrived at camp with

torn clothes and blackened legs, much in need of a bath.

Bears were often seen on

the mountain slopes which had been swept clear of timber by snowslides.

These were cinnamon bears. Stuart and I frequently went out on these

slopes in the hope of being lucky enough to shoot one. But we never got

near enough to a bear to do this. I took a shot at one at long range on a

venture. The bullet must have hit him; for he fell back on his haunches.

But after a few moments, he picked himself up and went off into the bush;

and nothing more was seen of him.

The building of the bridges

comprised in the Loop went ahead at a rapid pace; and so did the laying of

the track. It kept close on the heels of the bridge carpenters. At one of

these bridges, I remember seeing the tracklayers commence laying the track

at one end, just as the carpenters were finishing their work at the other.

G. H. Duggan was with me at

this camp for a short time. There was also another Duggan whom I met

frequently on this work. This was Con. Duggan. He was then timber

inspector for the railway company; so I was closely associated with him.

Some years later, he became well known in Calgary where he played a

prominent part as one of the leading men in the P. Burns Company.

From the Loop I moved camp

to a point near one of the company's Stores, generally spoken of as

Neilson's Store. W. G. Neilson, a younger brother of Matthew Neilson, had

charge of it. I had met him at Medicine Hat, but since then, he was always

so much farther to the front than I was, that I did not see him again

until I made this move. Now, I had at last caught up with him, and I was

delighted to renew my acquaintance with him.

There was a bridge across

the Illicilliwaet to be built there; and a few smaller ones. But none of

these took long to build. So I very soon had to move again.

My move this time was to

Albert Canyon, so named, it was said, after Albert Rogers, a nephew of

Major Rogers. He had been assistant to the Major in his exploratory

surveys.

The railway, at a point

near the Canyon, had to cross the Illicilliwaet again, on a fairly high

truss bridge. It was decided, however, to first build a temporary pile

bridge to be replaced by the truss later.

When we were starting to

build this temporary bridge, T. K. Thomson — whom I have already

frequently mentioned — appeared on the scene, immaculately dressed, white

shirt and all. He was on his way to a picnic, or other outing, which it

seems those on the staffs at Headquarters were from time to time

privileged to indulge in, with their wives and female relatives.

The pile-driving crew had

just got their staging for the pile-driver finished. This consisted of

logs stretched across the river. These logs were newly peeled, and

consequently were very slippery. But Thomson didn't stop to consider this.

He had to cross the river and no doubt considered himself in luck at

finding a means of doing this, conveniently placed there at his disposal.

So he confidently strode on to one of these logs. The result was no

surprise to me, but it certainly was to Thomson. He flopped into the

river, with one leg dangling over the log and both hands holding on to it;

and his body completely immersed. He gave quite a gymnastic exhibition in

his efforts to free himself from his predicament. Finally he succeeded;

and stood on the bank dripping wet. Then he stripped himself and wrung his

clothes. When wringing his shirt, he held it up and remarked to me, with a

grin: "Look at the boiled shirt, will you?" Whether he got to his picnic

or not I never heard.

The river bed at this

crossing was full of large boulders, which made the driving of piles

almost impossible. To add to this difficulty, wet weather had set in, and

the Illicilliwaet became a raging torrent. Just as the bridge was about to

be completed, it was swept away. So the work had to be done all over

again. This time, fortunately, it withstood the torrent; and the train

passed over.

After this, I moved camp to

a site a few miles from Twin Butte; close to Skenk's camp. Skenk was an

American, and was the engineer in charge of the grading on that section.

Apart from his special

engineering qualifications, Skenk was noted for his neat penmanship. His

figures and letters were very small, but perfectly distinct.

He had had as his assistant

an engineer named McKay, a highly capable mathematician; but more at home

in an office figuring out intricate calculations, than in practical work

in the field. He had some difference with Skenk, and Skenk discharged him.

I knew McKay well, having

frequently met him, and found him a most interesting man to talk with. So,

when leaving, he called at my camp and told me that Skenk had discharged

him. He also told me that he had written to Skenk telling him what he

thought of him. In this letter, he said, he told him that "his soul was

like his figures, small; but readable".

There was quite a large

trestle bridge to be built at Twin Butte. As it happened to be on Skenk's

section, it was he who had made the bill of timber required for its

construction, according to a standard plan for trestles with which he had

been furnished.

I found out, however, on my

first visit to the site of this bridge that, in making this bill of timber

Skenk had followed the standard plan too closely. It needed some

modification to make it fit with the conditions on the ground.

But in order to let the

carpenter foreman Bucknam get a start and carry on for a few days while I

amended the bill of timber, I laid out sufficient work that would not be

affected by any change I might make in Skenk's bill.

The following day I was in

my tent figuring out what changes it would be necessary to make in the

plan and in the bill of timber. It happened to be a pouring wet day, and I

had the entrance to the tent closed and drawn tight. I heard someone

outside trying to open it. So I got up and opened it myself; and was

confronted by Ross. "This is no doubt a comfortable tent to be in, Bone,

and carpenters waiting at Twin Butte for a plan of the bridge," was the

astounding greeting he gave me.

Having delivered this

thrust, he was about to leave. But, like Jacob in his wrestle with the

Angel, I was in no mind to let him go until he was in a better humour with

me. So I got him to come in and see for himself the tangle I was

endeavouring to straighten out. I told him the carpenters were not waiting

for a plan of the bridge; and that I had been there the day before, and

had laid out work enough to keep them going for some time. I showed him

both the standard plan and the bill of timber. He examined them carefully

and then abruptly demanded:

"Who made out this bill of

timber?"

"Skenk."

"Damn!"

This expletive was

evidently comprehensive enough to express all he had to say; for he left

immediately, apparently quite satisfied to leave the matter with me.

The following day I went to

Twin Butte, on the warpath myself. I had hitherto found Bucknam to be

capable and reliable, and I was at a loss to know why he had told Ross

that he was waiting for a plan of the bridge. When I put this question to

him, his reply was: "I didn't tell him I was waiting for a plan of the

bridge; he asked to see the plan, and I told him I hadn't got one."

This is a striking example

of how misunderstandings arise. The mere fact that Bucknam hadn't a plan

of the bridge, evidently led Ross to conclude that I was at fault in not

having furnished him with one; and that until I did so, the work would be

at a standstill.

However, all

misunderstandings were now over, and the bridge was built without delay;

and as nearly as practicable to the standard plan.

At this camp there was an

interesting meeting of East and West. An engineer who had finished his

work on the Onderdonk contract, and was making his way east, called at my

camp and had a meal with us. The conversation turned to the subject of

scenery; and our guest — whose name I cannot now recall — remarked that he

had been told that the farther east one went in the mountains, the more

beautiful became the scenery. I answered by saying that we had been told

quite the contrary; that the finest scenery was to be found the farther

one went west. The old proverb: Far-off fields look green.

The scenery at this point,

however, was equal to any in the Rockies; not so grand perhaps, but

softer. At any rate, it appealed to me so much that I made some sketches

of it. Bell-Irving happened to call at the camp about this time, and he

accompanied me and sketched the same scenes.

East met West at this camp

on another occasion. A packer with provisions from the coast — which he

was endeavouring to sell — called at the camp and displayed his wares.

Among them were some large Spanish onions which appealed to my.

gastronomic taste. I had not the ready cash to pay for them, but he was

willing to accept canned peaches in exchange. So I traded a case of these

for a sack of his onions. The onions at that time were a much greater

treat to us all in camp than the peaches.

About this time, Lord

Landsdowne, then Governor-General of Canada, paid a visit to the

Mountains, and I saw him riding along the tote-road with his retinue,

escorted by a guard of Mounted Police.

The embryo town of Farwell

(now known as Revel-stoke) gave him a great reception. Each side of the

street — there was only the one — was lined with fairly large-sized tops

of spruce trees stuck in the ground. This gave the appearance of trees

actually growing.

That was how Farwell looked

as I first saw it, when I camped in the neighbourhood after moving from

Twin Butte. It was the headquarters of the North West Mounted Police,

under Major Steele — better known in after years as Colonel Steele. It was

the headquarters also of Police Magistrate George Hope Johnston. I had met

Steele before, at Medicine Hat; but it was at Farwell that I first met

Johnston.

From Farwell, I moved to a

point on the other side of the Columbia near the camp of Ross and McDermid,

contractors for a portion of the grading.

There were a few fairly

large trestle bridges on this section, but no great difficulty was met

with in building them.

I next moved to a neck of

land between Victor Lake and Three Valley Lake, on which G. H. Duggan was

also camped. He was in charge of a section of the grading along the shore

of Three Valley Lake. But his work by that time was practically completed.

Tye had charge of the

adjoining section, and his camp was quite close to ours too. His work also

was almost completed. He was convalescing from an attack of mountain

fever, and was not very fit to do much work, as yet. He, however, had

Lewis as his assistant to take over the burden of the work.

Parenthetically, I may here

note that there were two engineers of the name of Lewis. But I cannot

distinguish between them by their initials; for these have quite escaped

my memory — if I ever knew them at all. But that is not to be wondered at,

seeing that, in general, everyone was called by his surname, without any

qualifying Christian name, or initials.

The Lewis who was with Tye

was the one whom I have already mentioned for his good water colour

sketches.

With these three camps

close together, we had an interesting reunion; and many stories to tell of

our experiences.

I was now on my last lap;

and I could already see the end. The bridges I had to look after were for

the most part small. The last of these was over the Eagle River, the

outlet of Three Valley Lake. On its completion the way was clear for the

final act, in linking by rail, on Canadian soil, the Atlantic with the

Pacific; generally spoken of as "Driving the last spike".

I was not present at that

ceremony. I was too busily engaged, as were the other engineers, in

packing up and getting ready to leave.

We carefully looked over

the clothing in our dunnage bags, and picked out what we thought was the

most respectable to travel in; and discarded the rest.

A coat which Duggan had

discarded caught my eye. It was made of bottle-green corduroy, and looked

to me much better than the coat that I had. So I picked it up and put it

on. It was thus in Duggan's cast-off coat that I travelled east.

We packed up the tents and

camp outfit, and placed them at a point beside the track, where it had

been arranged that a work train would stop and pick us up, with all our

baggage. We were waiting there all ready to help to load. But the train,

to our amazement, passed without stopping. We were left stranded.

We, however, made the best

we could of the situation. Tye's camp was still there. It was a wooden

building, and we spent the night in it. How we finally got to Farwell with

our dunnage bags and field instruments, still puzzles me. But we got there

somehow. The tents and camp outfit, however, were left behind.

For some time past I had

made up my mind to visit my old home in Scotland, on completion of my work

with the C.P.R. I had heard from Mather that he too purposed spending the

winter in Scotland. So we arranged to meet in Toronto; and then cross the

ocean together.

On my arrival at Farwell, I

learned from Ellison that a few engineers were to be retained in the

mountains during the winter to observe the effects of snowslides, to get

data that would be of value in the construction of snowsheds — work which

the company would in all likelihood start in the spring. He told me that I

could be one of these engineers if I wished. The offer was tempting; but I

decided to forego it, and trust to my getting a position on this work on

my return from overseas in the spring.

I called on Ross in his car

to say good-bye. He was beaming all over, happy at having successfully

accomplished a great work.

On my journey east, I

stopped a day at Calgary; and was greatly struck with the growth it had

made since I last saw it in the spring of 1884. W. T. Ramsay asked me to

stay the night with him in his bachelor quarters; and it was there that I

first met that grand Old Timer, Tom Christie, with whom Ramsay was then

sharing his quarters. We had a great evening.

From Calgary I continued my

journey; and when the train stopped for a few minutes at Regina, I learned

that Riel — the leader in the recent Rebellion — had been hanged there

that day. This would be about the middle of November.

I spent a day at Winnipeg,

and from there continued my way without any further stops, to Toronto. On

my arrival there, I went to my friends, the Erskines, with whom I had left

my trunk, containing some fairly decent clothes. I certainly needed a

change of clothing, for, according to Mrs. Erskine, I was a tough-looking

sight. But with the change of clothes, followed by a visit to a barber, I

became fairly presentable.

Mather arrived a few days

later, and we had a rare old time together. He had lots of stories of his

experience in New Mexico to tell me; and I had lots to say about mine in

the Mountains too.

We spent a week or ten days

in Toronto, and then took the train to New York, where we made the round

of a number of shipping offices, and finally took our passages on the

State of Nevada, sailing for Glasgow.

The voyage was uneventful,

but very pleasant. There were not many cabin passengers; just enough to

fill the smoking-room comfortably, and get well acquainted with each

other. They were mostly men from the West; and there was quite a

competition as to who could tell the tallest story. Mather and I took a

hand in this game too.

In my letters to my father

I had said nothing about my coming visit to him. I was keeping that as a

surprise until I got to Glasgow. On landing there I wrote telling him of

my arrival, and that I would be in Girvan, at a specified train time, the

following day. I spent the night in Glasgow with Mather, at his mother's

home.

On my arrival at Girvan the

next day, Father was at the railway station to meet me, and drive me home.

Needless to say, this was a very happy moment for both of us.

It was then but a few days

before Christmas; and Father and Robert had been invited by Aunt Wright to

Christmas dinner at Dowhill. It had long been her usual custom — which I

well remember — to have us all together as a family party, at Christmas.

Father had evidently been

quite pleased at the surprise I gave him; for he tried to pass the same

surprise on to Aunt Wright. The day I arrived home with him, he wrote her

saying that a visitor had just arrived to stay with him for some time; and

that he was taking the liberty of bringing him to this Christmas party.

But Aunt was alive to the

situation. She felt quite sure who this visitor must be. So she wrote back

that had she known that the young man who was the visitor was now in this

country, she would surely have included him in the invitation. But she

told none of the other members of the family except my cousin Bryce. This

was to be her surprise for the others.

I went to Dowhill by

myself, ahead of Father and Robert, so as to have a good talk with Uncle

and Aunt, and my cousins, before dinner. Bryce was the one I met first,

outside playing with a dog. Having got the tip from his mother, he knew me

all right. Then he took me in to see her. I shall never forget the

motherly hug she gave me.

One by one the others

appeared, and Bryce introduced me to them under some fictitious name. At

first they were quite taken in. But gradually it seeped through their

minds who I was. Then the laughter and fun which followed made a fitting

overture to the dinner. Father and Robert arrived in due course. At dinner

we were a merry party. I looked on it as an appropriate welcome home to

me; and a fitting close to my experiences in 1885. |