|

SURVEYS for the location of

the Short Line through Maine had been made by Alexander Middleton in the

fall of 1886; but there was considerable delay in starting construction.

This delay was due to

opposition raised by the Maine Central Railway, to the granting of a

charter to the International Railway of Maine — the charter under which

the C.P.R. purposed constructing this line.

In support of the

application for this charter, Middleton, at a sitting of the Maine

Legislature, gave evidence regarding the location of the line; and the

Legislature finally granted the charter. But by this time winter had set

in; and construction was consequently still longer delayed.

There was, however, a small

part of the Short Line in the province of Quebec, on which construction

had been started in the fall; and it was carried on during the winter.

This was the part between Sherbrooke and Lennoxville. Sykes and Hodgins

were both employed on this work; Sykes as division engineer, and Hodgins

as his assistant. But the rest of us at Sherbrooke remained unemployed all

winter.

As the saying goes, it's a

long lane that has no turning. And the turn came as a pleasant surprise,

early in spring, when we received from Ross the welcome order to go to

Greenville in Maine, and report to A. L. Hogg, the engineer in charge of

the work in Maine.

We lost no time in getting

there, and on our arrival, promptly reported to Hogg, now our new Chief.

I have already mentioned

him as having been in charge of location in the Mountains in 1883. I had

often heard about him; but this was the first time I met him. And I found

him very congenial and considerate to those under him.

There were a number of

engineers already at Greenville when we arrived; and among them was Foster

whom I had not seen for over a year. I was delighted to meet him again,

and we had a happy reunion in his room at the hotel, with some others, the

night of our arrival. He was, as usual, the life of the party.

Percy Girouard, a young

French Canadian whom I had not met before, also entertained us by his

stories and by his lusty singing of Alouette. He was a graduate of Royal

Military College; and was then employed as a draughtsman in Hogg's office.

He later joined the Royal Engineers, and served with distinction under

Kitchener at the relief of Khartoum. He was afterwards made Director of

Railways in South Africa; and was knighted for his services in this

connection during the Boer War.

On the following morning,

Hogg joined us at breakfast. As he smilingly looked us over, there was an

understanding twinkle in his eye; from which it was easy to see that he

knew all about our little diversion of the night before.

To facilitate construction,

the line in Maine was divided into divisions of about thirty miles, each

in charge of a division engineer. These divisions were subdivided into

three sections, each in charge of an assistant engineer.

Middleton was in charge of

the farthest east division, which connected with the Maine Central Railway

at Mattawamkeag. I was to be his assistant on the central ten mile section

of this division. His other assistants were Schreiber on the western

section, and Simpson on the eastern.

H. B. Wright was assigned

to me as rodman. He had been on the Lake Superior division of the C.P.R.

during construction; and he was one of those who had spent the winter with

me at Sherbrooke. So I knew him well.

After spending a day or two

at Greenville getting our camp outfit together, Wright and I set out for

Lincoln, a small town on the Maine Central, and the nearest one to my

section. There was, however, no direct railway connection between

Greenville and Lincoln. So we had to go by a roundabout way, involving

some tedious waiting in changing from one railway line to another.

Eventually, we got to Lincoln all right.

Middleton had not yet

arrived; but Sinclair, the contractor for the work on my section, was

there ahead of me. He had already established his camp and was busy

clearing the right of way. So I got him to move my camp outfit to a site

close to his own camp. This was situated about ten miles north of Lincoln,

on the other side of the Penobscot River; and about the middle of my

section.

A day or two after I had

got settled in camp, Schreiber appeared on the scene. He had been sent by

Hogg to stay at my camp until Middleton came; and to assist me in the

meantime.

Schreiber's arrival was

most opportune; for I was about to make a slight change in the location of

the line to lighten the work on a large cutting near the camp. So I could

well make use of his valuable help.

There was still some two to

three feet of wet slushy snow in the woods, and snowshoes were a

necessity. We had none of our own, but we managed to get some pairs at

Sinclair's camp. They were pretty well worn out, but we made good use of

them while they lasted.

One day, however, Schreiber

got badly entangled with his pair. They had got so rotten with the wet

slushy snow that his feet went right through them down to solid ground;

while the snowshoes clung around his legs above the knees, like spurs on a

fighting cock. It was a comical sight to watch his contortions in trying

to free himself.

Middleton arrived just as I

had finished making this change of location. He gave it his approval; and

stayed at my camp for a few days. When he left, he took Schreiber with

him, and established a camp for him on the western section.

Middleton opened an office

for himself in Lincoln. But he was much more in his element out on the

work, than in his office. He was a man of even disposition, quiet and

unobtrusive; but with a keen sense of humour. My relationship with him on

that work was of the happiest, and developed into a lifelong friendship.

For the first few months I

was kept busy laying out the work. There was much variety in this, for the

railway did not follow a natural valley route. It cut through a series of

ridges; and across intervening valleys, and rivers which were tributaries

of the Penobscot.

There were many large

granite boulders strewn over the ridges, and from these boulders — by the

use of plug and feathers — large slabs for the building of culverts, and

abutments of bridges, were readily obtained.

The bush was all second

growth; so there was no large timber. But there was a ready market for

such timber as there was, at the spool factories, and toothpick factories,

which were established along the banks of the Penobscot River.

In the valleys between the

ridges, there was some swampy land through which we sometimes had to

flounder. On one occasion when we were thus engaged, Wright burst into

song with these lines:

"Beautiful bush, with

beautiful trees,

Beautiful swamps, with mud up to your knees,

Beautiful lakes, and rivers as well,

Beautiful, beautiful, beautiful sell."

This poetic effusion he

ascribed to Secretan. But whether or not it was Secretan's, it was

particularly applicable to our own situation at the moment.

About this time, H. D.

Lumsden — my old Chief on the Ontario and Quebec Railway — was appointed

Chief Engineer of the Short Line; and Hogg became Assistant Chief on the

part in Maine.

When I had got the work on

my section all laid out, I had time to spend an occasional week-end in

Lincoln and enjoy some social life. Wright generally accompanied me.

Schreiber too, although his camp was much farther than ours from Lincoln,

would at times join us in these week-end visits. Simpson, however, but

rarely took part in them. He was married; and quite naturally spent his

leisure time in camp with Mrs. Simpson. Moreover, Winn, a small town some

twelve miles east of Lincoln, was quite close to his camp; so when he had

need to go to town, it was to Winn that he went.

Chan Woods, the

hotel-keeper with whom we stayed when in Lincoln, busied himself on our

behalf, and introduced us to a number of families in the town. And by

these we were received most hospitably. We were always made welcome at any

time we chose to call.

Middleton used to tell a

story about Schreiber, apropos of one of these visits. They were visiting

a family in which there was a new baby; and they found a number of ladies

there too, all in ecstasies over this wonderful baby. One of these ladies

turned to Schreiber and said:

"Don't you want to kiss it,

Mr. Schreiber?"

"I don't want to, but I

will," was his rather surprising reply — a reply which, however, reflected

perfectly his genial good nature.

We would sometimes visit

also our neighbouring engineers at Brownville, which was the headquarters

of Matthew Neilson, the engineer in charge of the division adjoining

Middleton's on the western end.

William Mackenzie and D. D.

Mann, who each had had separate contracts in the mountains on the

construction of the main line, had now joined forces; and had taken a

contract on Neilson's division, under the firm name of Mackenzie & Mann.

Brownville was their headquarters too.

Although the construction

of the railway was being pushed ahead, no settlement had yet been made on

my section for the land required for right of way, and toward the end of

1887, arbitration proceedings were about to be taken for its acquirement,

before a judge of the court in Bangor.

Sinclair, the contractor,

was also a party in this arbitration, as the owners of the land to be

acquired had included in their claim against the railway company the value

of the timber destroyed by him in connection with the building of his

camps.

At the time set by the

court for the hearing of evidence, Middleton, unfortunately had to go to

New York to be with his elder brother George, who was about to undergo a

serious operation. But, before he left, he asked me to go to Bangor in his

stead; and give what evidence I could if required. It thus devolved on me

to go to Bangor, instead of Middleton; and Sinclair went with me.

The court proceedings were

quite informal. The owners of the land were there with their witnesses.

The chief of these was a land surveyor who gave evidence as to the value

of the timber destroyed. He was afterwards cross-questioned at length by

the solicitor for the railway company, who brought out various

inconsistencies in his methods of valuation.

At this point, Sinclair

suggested that the judge, being himself an old lumberman with a good

knowledge of timber-land values, might like to visit the lands in

question, before coming to a decision. To this suggestion the judge and

both parties were agreeable; and a day was fixed for his visit, on a date

when Middleton would have returned from New York.

Although I well remember

the appearance of the judge and also the appearance of the solicitor, and

the surveyor, their names have completely gone from my memory. So I can

only designate them by their professions.

On the morning of the day

fixed for the judge's visit — it was in the winter — Middleton, Sinclair

and I were at Lincoln to meet him. He arrived accompanied by the surveyor,

who had travelled with him from Bangor; and both had breakfast together at

the hotel. In the meantime, Middleton and Sinclair were devising a way to

separate the surveyor from the judge, on the inspection trip.

The way this was to be done

became very soon apparent. For, when the judge and the surveyor, having

finished breakfast, were standing outside on the hotel porch, waiting for

the conveyance which was to take them to the land to be inspected,

Sinclair drove up to the hotel in a single-seated cutter; and suggested to

the judge that he would find the cutter much more comfortable than the

double-seated sleigh which Middleton was bringing up behind.

With this suggestion the

judge readily concurred, and took his seat beside Sinclair. The cutter

then started off at a brisk pace; and the surveyor, now separated from the

judge, had to take his place beside me in Middleton's sleigh, which came

along a few minutes later.

Middleton held back his

team, in order to let Sinclair For such material, the contract price was

quite inadequate. So the contractors were having no easy time in meeting

expenses.

They finally came to the

conclusion that they had either to get a considerably higher price for

earth, or let the railway company take over the work.

They had several meetings

with the head officials of the company in Montreal, regarding their

position; and the company at length decided to get R. G. Reid — a noted

contractor with large experience — to go over the work and make a report

on the probable cost of completing it.

Reid undertook this work;

and one day Hogg, Middle-ton and I, met him at Sinclair's camp. There was

a cutting being made through a high ridge close by; and the greater part

of the material was quite evidently "hardpan". Reid examined it carefully;

and questioned me as to the classification I had been making of this

material. My answers evidently satisfied him, for as soon as he had

finished, he gave the word to pass on to the rest of the work.

We all then got mounted on

horseback and set out on our way, with Reid leading, at a gallop. I was

next in the lead, but Middleton after a time managed to catch up to me,

and suggested I should keep alongside of Mr. Reid and give him all the

information I could. This was easier said than done; for it was a wild

ride over stumps and boulders, which littered our path. Reid proved to be

the best horseman of us all, or it may be that he just had the best horse;

for he still kept the lead; with Hogg trailing far behind.

Reid stopped for a few

minutes now and then, to examine the material in certain cuttings; but in

the main, he kept going. So he was not long in passing over Middleton's

division, and into Neilson's. There, Middle-ton's part in the inspection

ended; so we turned about and headed for our own camp. Hogg, however, went

on with Reid.

Middleton and I came back

at a much slower pace; we had had enough of hard riding. But with this

slower pace, it was getting dark before we reached camp; and it was

anything but pleasant riding, picking our way in the dark through stumps

and other obstacles.

So, when we came to a part

on my section that I knew well, I thought of a way to make the going

easier. There was quite a long borrow-pit by the side of the trail along

which my horse was stumbling; and I considered this pit would make easier

travelling, even although it contained about two feet of water. So I quite

confidently made my horse step down into it.

But I had overlooked one

thing. The bottom of this pit, I knew, was firm clay; but it did not occur

to me that it would be slippery. It was left for my horse to find that

out; for the moment his feet touched the clay bottom, they slid with a

swish through the water, and over he went on his side.

Just then, I heard

Middleton's voice calling out: "Where are you going, Bone?" By that time I

was under water, all but my head. But I still had hold of the reins; and

was free from the saddle. So I managed to get on my feet; and get my horse

on his too. I then led him through the water to the end of the borrow-pit

on to dry land; and there I mounted again, dripping wet.

We got to Sinclair's camp

shortly afterwards, and turned over our horses to the stable men. I heard,

as we were leaving, the man who took my horse remark to the other: "They

must have been riding fast; this horse is wet all over." I did not think

it necessary to correct that impression.

Middleton afterwards took

delight in telling that story on me; with just sufficient exaggeration to

make it the more amusing. In relating the incident, he would say that I

was completely under the water, and that he could see nothing but bubbles

coming up.

Following Reid's

inspection, and report, the railway company granted the contractors an

increase of 50% on their contract price of 25 cents per cubic yard for

earth; thus raising the price to 37½ cents. This was satisfactory to the

contractors, and they carried on, and finished their work.

Later in the summer,

Middleton got the offer from a New York group of financiers of a position

in Brazil. This was to make an exploration by boat of the Tocantins River,

a tributary of the Amazon, and report on the feasibility of its being

economically navigated.

He accepted the offer; and

resigned from his position with the railway company. We, who had worked

with him, were all sorry to have him go. And so were the people of

Lincoln. I would not venture to say how many of his lady friends were at

the station in a body the day he left, to bid him good-bye, and wish him

Godspeed.

The work was by this time,

so well advanced, that there was hardly any need for a division engineer.

So I became acting division engineer instead. This entailed but little

extra work on my part; for Simpson's section was practically finished; and

my own too. The work still to be done lay, for the most part, in

Schreiber's section.

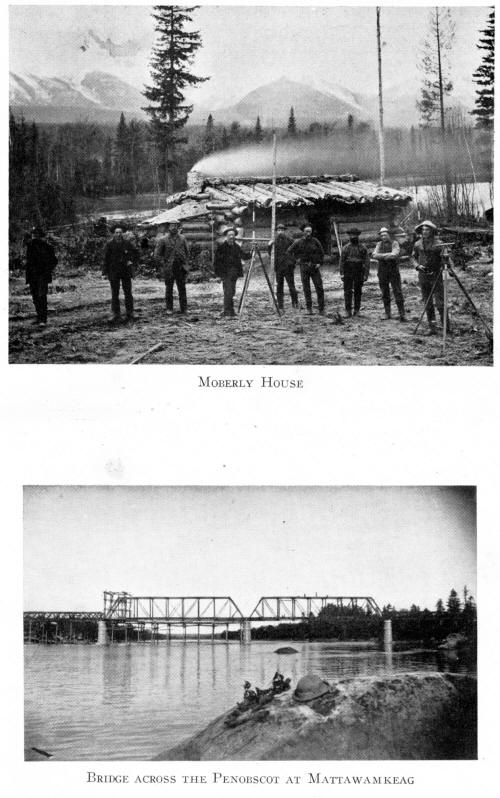

So I gave up my own camp,

and took up my abode with him. I spent my time partly at his camp and

partly at Lincoln. But I also spent some time at Mattawamkeag, while the

steel bridge over the Penobscot was being erected.

In the latter half of the

year 1888, political questions were being hotly discussed, as this was the

year of a presidential election in the U.S.A. In this election, Benjamin

Harrison, Republican candidate, won against his opponent, Grover

Cleveland, the candidate of the Democrats. I heard much wailing in Lincoln

over this result, by some Democrats who had been holding government

positions.

Towards the close of the

work, Lumsden came to Lincoln to see me. He informed me that track-laying

would be starting immediately at Mattawamkeag; and he wanted me to look

after this work temporarily, pending the arrival of Ramsay — an engineer

experienced in track-laying — who would then take charge. Lumsden told me,

too, that he had made arrangements with a man named Burns to board the

track-layers in a boarding-car; and I would not therefore be troubled by

that.

A day or two afterwards, I

got word that the cars with the track-laying crew were on the way to

Mattawamkeag; so I went there to meet them. But when the cars arrived they

were without provisions; there was nothing at all for the men to eat. The

man Burns, mentioned by Lumsden, had apparently fallen down on his job, to

the intense indignation of the men. And I had to bear the brunt of this.

I was early on the look-out

for Burns the following morning. I met him in the middle of the main

street; and there we had a hot wordy battle. But it did not take him long

to remedy the slip he had made. I can see him yet, rushing around from one

store to another getting provisions for his boarding-car.

This was the same Burns who

in after years was known in Calgary as Pat Burns; and later as Senator

Burns.

That same day, a slim young

man who was Burns' clerk approached me, and introduced himself by saying:

"I'm George." Although I did not recognize him from his appearance, the

name "George" at once recalled to mind the small office boy I had first

met at Medicine Hat in 1883 — George Webster, who many years later became

Mayor of Calgary; and afterwards a Member of the Alberta Legislature.

The erection of the bridge

across the Penobscot was now sufficiently advanced to permit the

track-laying cars to cross; so track-laying was commenced at once; and by

the time Ramsay arrived and took charge, about twelve miles had been laid.

I stayed a few days with

him; but as there was nothing more there for me to do, I left for

Sherbrooke where I made my final report in person. There I spent a few

days; and met many old friends, among whom were Mather, Hodgins, Stoess,

and Holt. Holt had then a contract for part of the work on that division.

Schreiber and I had

arranged some time before, to take a trip together to the old country,

after the work was finished. And this we did. We sailed, later in the

year, from New York to Glasgow, on the steamship State of Nebraska.

It was a few days after

Christmas that I arrived at my old home. There was not, however, the joy

attending this home-coming that there was in the previous one. For

although I was glad to find my father hale and well, and my brother Robert

too, there was a sad change at Dow-hill. No warm welcome there from my

Aunt Wright this time. Both she and Uncle Wright, and also my cousin

William, their eldest son, had passed away; and James, the youngest son,

was carrying on the farm alone. |