|

I ARRIVED at Regina about

midnight, and put up at the Windsor Hotel. The following morning, who

should call on me but the ubiquitous "George" whom I had last seen in

Maine. Holt, he told me, had gone north on an inspection trip to

Saskatoon, but before leaving, had instructed him to take me to Neilson's

camp; he had, he said, a team of mules and a buckboard waiting outside,

all ready to take me there. So I set out with him at once.

The camp was in the

Qu'Appelle Valley, about twenty-five miles north of Regina. There I

learned that I was to be transitman, under Neilson, on the location of the

railway which was to connect Regina with Prince Albert, by way of

Saskatoon.

For the information of

those to whom the word "Transitman" means nothing, I may say that on the

location of a railway across a wide expanse of open prairie, the duty of

the transitman was much the same as that of a navigator of a ship; for in

order to reach his objective with any degree of certainty, he had to keep

a log of the course run each day; and plot these in camp at night.

A company with the

comprehensive name of "Qu'Appelle, Long Lake, and Saskatchewan, Railway,

and Steamboat Company" had, some years before, built the part of this

railway from Regina to the Qu'Appelle valley. This part, however, was not

being utilized; and the roadbed was a tangle of weeds.

As its name would indicate,

this company had planned to put steamboats on Long Lake, to be run in

conjunction with the railway. With this object in view, a wharf had been

built on Long Lake, at the end of the completed portion of the railway.

But by the time the wharf

was built, a period of dry seasons had commenced; and the shore of the

lake kept receding until the wharf was entirely on dry land.

That the drying up of the

lake was not an extraordinary occurrence was shown by the fact that at the

site of the wharf, and well past the end of it, there were old buffalo

trails, and well-worn Indian travois ruts, plainly to be seen. This was

good evidence that that part of the lake had been dry in the past, long

before the wharf was built.

So the plan to navigate

Long Lake was naturally abandoned; and an all-rail route was the project

on which I was to be employed.

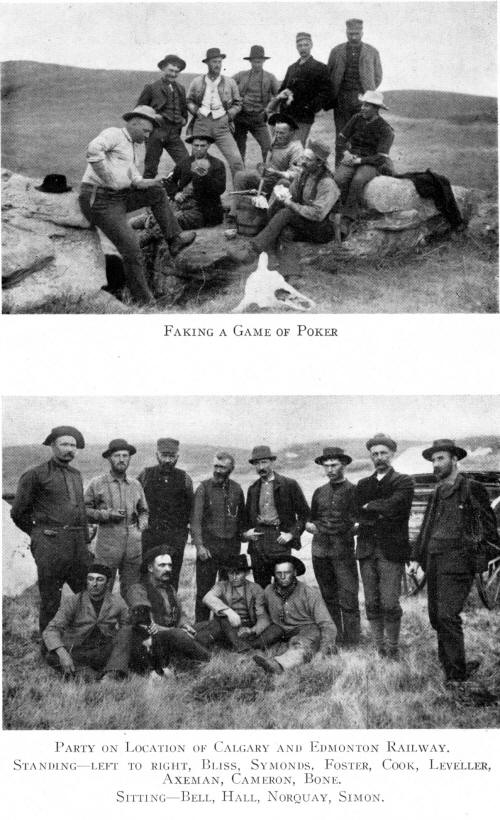

James Ross had undertaken

the engineering and construction of this railway; and associated with him

in this were Holt, Mackenzie, and Mann. H. D. Lumsden was the inspecting

engineer for the government.

I started work under

Neilson who, at first, was the engineer in charge of location. He,

however, was shortly afterwards put in charge of construction; and

Alexander Stewart took his place on location.

The starting point of our

location was in the Qu'Appelle valley, at a siding on the built portion of

the railway, called Craven; and Saskatoon was our first objective.

A few days after I had been

at work, Holt called at our camp on his way back from Saskatoon, and had

lunch with us. In the conversation I had with him, he referred to my new

position. He said that seeing my experience had all along been on

construction, it would be well that I now got some experience on location;

and that was why he had placed me on location. I expressed my thanks for

his consideration, and assured him that I was well pleased with my new

job.

Some two weeks later, when

we had moved camp from the valley, and were camped on the uplands, we had

quite an alarming experience. This was on a Sunday when we were resting

quietly in camp.

Stewart had gone for the

day to Regina, and I was left in charge of the camp. One of our teamsters,

too, had gone with his team to get them shod at Craven.

We were suddenly roused by

the rumble of a wagon, tearing along with the team at full gallop, and a

voice yelling "Prairie fire!" This was our teamster who had gone to get

his team shod. He had seen that a prairie fire, fanned by a strong wind,

was approaching in our direction; and he had turned back to warn us. And

he was not a minute too soon.

We started immediately to

create a safety zone by setting fire to the prairie on the lee side of our

camp; and just had time to take down the tents and drag them, together

with the rest of the camp outfit, on to the safety zone. We could feel the

heat of the flaming billow, as it approached. But it snuffed itself out

the instant it reached the border of our safety zone. There was nothing

there to keep it alive. So our camp was saved in the nick of time; and

perhaps ourselves too.

Not long after this

encounter with the prairie fire, we had a visit from Ross and Mann, who

stayed at our camp over night. Mann entertained us with stories of his

experiences in South America. He had gone there after having finished his

contract in Maine, to look into the prospects for railway construction,

and had but recently returned. Some of his stories were pretty

far-fetched; and they elicited the remark from Ross: "As true as you can,

now, Mann."

I cannot recall who the

leveller on our party was when we started. Noel Brooks, from Sherbrooke,

was with us for a short time before being transferred to a construction

camp. But whether it was he who had been our leveller, I cannot now say.

Pyne, however, joined our party in this capacity about the end of August.

Between Craven and

Saskatoon there was a great scarcity of good drinking water. Such water as

there was, was strongly alkaline. Little wonder then, that we all longed

to reach Saskatoon, and get a good drink from the Saskatchewan. But such

was the irony of fate, that when we did get there — about the middle of

September — it was a cold chilly day; and no one had any desire for a

drink.

When we reached Saskatoon,

Pyne was transferred to construction; and Kirkland joined the party as

leveller in his stead. I had spent the winter of 1886-87 with Kirkland in

the Magog House at Sherbrooke, and knew him well.

Saskatoon at that time

consisted of a few houses on the south side of the Saskatchewan. The

principal of these — as far as we had any dealings with them — was a

general store; and close to it, a blacksmith's shop.

We spent some two or three

weeks there running trial lines for a crossing of the river. When we had

finally established the site of this crossing, we moved camp to the north

side of the river; and continued the location of the line on that side, on

to Prince Albert.

We made good progress until

we got to Duck Lake; but there we entered a bush country, and this slowed

down our progress considerably.

This was a district of much

historical interest. It was here, and in the neighbourhood, that the

battles in the Riel Rebellion had been fought in 1885. We camped at one

time close to where General Middleton had had his headquarters' camp.

Empty tin cans, and other camp debris, were still there in evidence.

Toward the middle of

November winter set in, with sub-zero temperatures and heavy snowfalls.

But being in the bush, we were well sheltered, and did not feel the

severity of the weather as much as we would have felt it had we been on

the open prairie.

We finished the location to

Prince Albert about the end of November. The length of this location —

starting from Craven — was approximately 230 miles.

As soon as we had finished,

our camp outfit started back, in charge of Kirkland, on its way to End of

Track, which by this time was about half way between Saskatoon and Craven.

Stewart and I, however,

stayed for a night at Prince Albert, at the Queen's Hotel; and on an

invitation from Charles Mair — well-known Old Timer of Prince Albert, and

poet and writer — we spent the evening at his home. He had two attractive

young daughters, whose presence added much to our enjoyment of the

evening.

The following day, we were

busy getting together our own outfit for the journey back. This consisted

of a small sleigh, or jumper as it was called, and a pair of ponies. We

loaded the jumper with a small tent, our blankets, and some provisions.

We set out on our journey

about five o'clock in the afternoon and made for the home of a settler

named McInnes, who, we had been told, would put us up for the night. We

had supper with him; and spent a comfortable night.

Our next stop was at Duck

Lake. We put up at a hotel for the night; and I had a pleasant surprise in

meeting there, two old acquaintances — Madigan, who had been a contractor

on the construction of the C.P.R. in the mountains; and Watson, whom

I had met at Sherbrooke. They had a winter's job there, cutting ties for

the railway.

We crossed the Saskatchewan

the following day on the ice, near Batoche — the scene of one of the

battles in the Rebellion. There was still evidence of that battle, in the

shattered trees which bordered the river.

We had our mid-day meal

almost opposite Batoche, on the south side of the river, at the home of a

French Canadian. We then continued our way, hoping to reach Saskatoon by

night. But we were now on the open prairie; and a strong wind was blowing,

sweeping the snow before it, and obliterating the travelled trail. The air

was so filled with snow that we could scarcely see ahead of us. We

therefore had to plough our way through the snow without having any

definite idea where we were going; and to make matters worse, darkness

overtook us.

After thus wandering for

some time, we saw a light and headed for it. As we got near it, we saw

that it came from a log house which loomed up through the darkness. So we

drove on to this house and there made our plight known.

The occupant, who was

keeping bachelor's quarters, kindly invited us in to stay with him for the

night. And he cared for our ponies too. He turned his own team out of the

stables, and let them fend for themselves in the yard, in order to let our

ponies in and be sheltered for the night. He then set to work and cooked a

good supper for us. His hospitality knew no bounds; and we certainly

appreciated it to the full.

After supper we had an

interesting talk with him; exchanging stories of our experiences. His

name, he told us, was Clark.

When it was time to go to

bed, we spread our blankets on the kitchen floor, beside the well-filled

stove, and passed the night in perfect comfort.

By morning the storm had

blown itself out; and we continued on our way. We caught up with the rest

of our party about noon, at Saskatoon, where they had camped the previous

night. The storm had played havoc with the cook's tent. It blew it over,

and in doing so, it upset the cook's alarm clock into a pail of water,

where it was found in the morning encased in a solid mass of ice.

We had our mid-day meal

there, and then set out for Blackstrap Coulee, which we reached about 10

o'clock at night. There we found Brooks and his party in bed in a hayrack,

among a load of hay. They were on their way to a job for the winter in the

bush country around Duck Lake, to superintend the cutting of ties.

Our next stop was at a

place called Springs, which we reached in the evening after a long cold

drive, in a temperature well below zero. Here we found the bridge

carpenters' camp; and two of my old associates in the bridge-building days

in the Mountains. The first one I ran across was Weller. He had been one

of the foremen carpenters then. Now he was in charge of the bridge

building on this railway.

His first greeting to me

was the exclamation: "Where have you come from; the North Pole?" With the

buckskin coat, and the tuque I was wearing — and very likely some icicles

hanging from my beard — I may well have appeared to him as having come

from some frozen region in the Far North.

Whom should I meet next but

my old Chief, George Ellison; and his greeting was most cordial.

We had supper at that camp;

and stayed for the night. Next day we got to the End of Track; and from

there by train to headquarters, in the Qu'Appelle valley, close to Craven.

There, Stewart and I stayed

a few days finishing our plans of the location; and, incidentally, getting

the latest word regarding future developments. We learned that work on the

Calgary and Edmonton Railway would, in all likelihood, be under way the

following year; and that — in that event — we would both be employed on

it.

Construction work was now

being closed down for the winter; and many were leaving for their own

winter quarters. So as soon as I was free to leave, I made my way to Ailsa

Ranch, which I reached a few days before the end of the year; and settled

down there, quite contentedly, for the winter. |