|

On April 1, 1999 the

map of Canada was re-drawn: the Northwest Territories divided into two

territories to allow for the creation of Nunavut, a homeland for

Canada’s Inuit.

On April 1, 1999, the map of Canada was redrawn: the Northwest

Territories divides into two territories to allow for the creation of

Nunavut, a homeland for Canada’s Inuit. The creation of Nunavut is

testament to the strength of Inuit political leaders and to the

flexibility of Canadian political institutions.

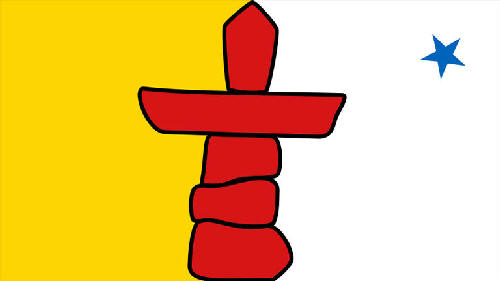

Over the past six years, Inuit leaders have been busy preparing for this

event. Everything from new symbols on flags and licence plates to new

buildings to house a legislative assembly to new electoral districts and

election of a new governing territorial assembly has been prepared in

anticipation of this moment. And now, the real work begins.

The new territory of Nunavut is geographically large, with a unique

variety of landscapes and ecosystems. The whole territory, from the

glacial mountain fiords of the east coast of Baffin Island to the

rolling rock hills of the west coast of Hudson Bay, is arctic terrain,

which means that it is all to the north of the treeline.

What remains of the N.W.T. is frequently called the western Arctic but

more appropriately should be called subarctic, since the vastest portion

of that territory lies within the treeline. Nunavut can best be

described with reference to the distinctive culture, history, and

politics of the majority of its inhabitants, who are Inuit.

Inuit is an Inuktitut language word for people. Inuk for person. For

much of recent history they were known as Eskimos, but obviously

preferred the substitution of their own term for themselves. While the

striking aspects of their material culture are well known — iglu (snowhouse)

and kayak (small boat) perhaps better than ulu (woman’s knife) and umiak

(large boat) — their intellectual culture and values have served Inuit

as well in the modern world as their unique technology did in earlier

ages.

For the most part, Inuit prize flexibility and ingenuity — a good idea

is not something to hold back in the interest of maintaining the way

things were always done. At the same time, elders and ancient traditions

are highly respected. Balancing these two — an appreciation for newness

and respect for the wisdom of the ages — will be one of the challenges

of Nunavut.

Archaeologists maintain that modern Inuit, who certainly have a language

and culture distinct from that of other indigenous Americans, are the

descendants of Thule peoples who were late (and last) to cross the

Bering Strait, coming as recently as a millennium ago. Inuit have a rich

legacy of creation stories, some of which affirm their belief that they

were placed in their homeland by their own creator.

Traditional Inuit culture remains strong in Arctic communities because

Inuit continue to depend to a great extent on hunting to get enough food

to survive (and food sharing remains a critical aspect of community

economies).

Inuit visual arts have provided strong expressive mechanisms for the

transmission of Inuit culture, and the Inuit language, Inuktitut, has

remained resilient, due in part to a deliberate policy of Inuit leaders.

In the playgrounds of the many Arctic communities I have visited, the

language of play has been Inuktitut — surely as good an indicator as any

of a language’s vitality.

The history of the Arctic is rich and complex. Though most historians

have focused attention on explorers and expeditions, cultural contact in

the Arctic and Inuit responses to colonialism are compelling themes that

will continue to gain increasing scholarly and public attention.

Although nineteenth-century whaling had some local impact, for the most

part Inuit economic life remained in its indigenous pattern until the

fox and seal fur trades of our own century.

Hence there were Inuit Canadians who as late as the 1950s had little or

no exposure to outsiders. Permanent settlement into communities was for

many Inuit a phenomenon of the fifties and sixties. One of the biggest

challenges facing the leaders of Nunavut will be to find a way out of

the economic dependence that has become the most debilitating legacy of

colonial relations. Many of those leaders were born “on the land” in

what amounts to another world.

Politically the Arctic islands became part of Canada in 1880, though

virtually nothing was done about them until 1897 when William Wakeham,

co-chairman of an international boundary commission, ceremonially

hoisted a flag at Kekerten Island in Cumberland Sound, now a historic

Territorial park.

It was not until 1921 that an appointed council composed of Ottawa-based

civil-servants, began to actively govern the Arctic and instituted the

series of annual eastern Arctic ship patrols that brought supplies and

services to coastal communities.

The status of Inuit, legally uncertain, was settled in 1939 in the

Supreme Court of Canada decision Re: Eskimos, which determined Inuit

were a federal responsibility and in effect, aboriginal citizens;

however, Inuit were not directly consulted about the governance of their

lands and communities until the late fifties. In 1965 Abraham Okpik

became the first Inuk appointed to the territorial council. In 1966 the

council expanded to include seven elected members, with Simonie Michael

the first Inuk elected.

Slowly the territorial council evolved into an elected, representative

body, with Inuit actively involved in its workings. By the early

seventies, Inuit in N.W.T. also organized themselves into the Inuit

Tapirisat of Canada, an association with a broad mandate to preserve

Inuit culture and promote Inuit interests. By the eighties, the ITC

represented Inuit across the nation.

Nunavut was a long-standing goal from the ITC, which presented the

notion formally as early as its first land claim in 1976. A lengthy

treatise would be needed to detail the twists and turns around the

question of division that occupied Inuit politicians in the late

seventies through the eighties. Suffice to say, however, that a

generation of astute political leaders emerged among Inuit, many of them

women, who with patience, determination, creativity, and will achieved a

vision: Nunavut.

Nunavut is an Inuktitut word for “our land.” Unlike other First Nations

in Canada, Inuit have not been interested in separate governing

institutions. Rather, their particular situation as majority occupants

of the Arctic has led them to promote the notion of increased power for

their public governments (as opposed to aboriginal governments) as a

vehicle for their political aspirations. They will be able to use their

substantial majority to elect enough Inuit politicians that the

government of Nunavut will be theirs. At least, they are able to do so

for the foreseeable future.

Nunavut is in part the creation of a land claim, the 1993 Nunavut Land

Settlement Agreement, which stipulated in one section the division of

the N.W.T. The land claim is now administered by a body called the

Nunavut Tungavik Incorporated, which, as a large capital and landholder,

will be a major player representing the Inuit interests in Nunavut.

Recommendations setting up the Nunavut government were made by a body

called the Nunavut Implementation Commission. It was chaired by John

Amagoalik, widely acknowledged as a founder of the territory. Its work

ended in 1997 when an interim commissioner, former member of parliament

Jack Anawak, was appointed to carry out its recommendations.

Over the past six years, the Inuit community has been engaged in

frenetic activity to have in place by the April 1, 1999, deadline, the

human and material infrastructure demanded by the new government. Over

the next eight years increased responsibilities will be devolved to the

Government of Nunavut. By the end of that time it will be a

province-like jurisdiction as the N.W.T. is today. Inuktitut is an

official language in the new territory.

The capital of Nunavut is Iqaluit (formerly Frobisher Bay), but every

attempt has been made to decentralize and develop regional centres.

There are three main regions in Nunavut: the communities on and near

Baffin Island, the Kitikmeot communities on the coast and islands of the

central Arctic, and the Kivilik communities in the region of the

northwest coast of Hudson Bay.

Every one of the twenty-six Nunavut communities (the total population

amounts to a mere seventeen thousand) is its own unique microcosm, and

each has developed its own strategy for dealing with the traumas of the

past and the challenges of the future. The difference, for example,

between Rankin Inlet, which on the surface has the rough-and-ready feel

of a northern resource town, and nearby Whale Cove, where an older

rhythm of life still prevails, is striking.

While many would assess Nunavut’s ultimate chances based on its oil,

gas, and mineral resource base, it should be noted that there is another

resource with which Nunavut remains strikingly endowed — the continued

presence of elders who hold a treasure-trove of invaluable knowledge,

stories, skills, and values. Culture itself is one of the truly great

assets of Inuit.

For better or worse, so-called “authentic” aboriginal culture — and the

commodities it can produce — will only increase in value over the next

century. The degree that Nunavut, in its very forms of operation and

decision making, reflects, embodies, and conveys the Inuit culture from

which it has emerged, may ultimately determine its chances of success.

This article originally appeared in the April-May 1999 issue of The

Beaver. |