|

THE MOUNTAINS OF THE

ALEXANDRA ANGLE (Mistaya and North Fork Valleys. Pinto Pass and Lyell

Glaciers)

“There are none the

less moments of irrational passionate revoltmoments in which one would

buy back with a year of the life that is left one solitary hour among

the untroubled mountains of youth”

Arnold Lunn

It was the unfrequented

region surrounding Mount Columbia, a land almost “lost behind the

ranges,” which lured Dr. William Ladd and myself into joining forces on

our Expedition of 1923. During winter days we had spent hours in poring

over available maps and photographs, familiarizing ourselves as best we

could with the geography and history of North Saskatchewan headwaters.

We were to visit an area much less compact than the Freshfield Group,

with peaks carved on a vaster scale and more widely separated. It was

plain that the Columbia Icefield must be crossed, in part at least,

before climbs could be made; we knew that the distances were very great.

A further incentive was the fact that the mountains were situated near

the limits of journeys made by earlier explorers, whose observations had

frequently been made under conditions that precluded satisfactory

results. There would be work for us to complete.

The terminal branches

of the North Saskatchewan, as our map-dissection revealed, find their

sources chiefly in the eastward drainage of the Continental Divide,

between Howse Pass—in the northern Waputiks—and Mount Columbia. Mistaya

River, locally known as Bear Creek or the “Little Fork,” flows northward

from Bow Pass, receiving streams from the Waputik ice through Peyto

Glacier, and joining the main Saskatchewan between Mounts Sarbach and

Murchison.

Howse River, the

“Middle Fork,” flows from the Freshfield Group, and also receives

streams from Bush Pass, as well as from the Lyell Icefield through

Glacier Lake. The third branch, the North Fork, comes from Sunwapta

Pass, which, in the north, separates Saskatchewan from Athabaska

headwaters. The North Fork has its chief source in the Saskatchewan

tongue of the Columbia Icefield, but its volume is soon increased by

Alexandra River, its old “West Branch.”

Howse River and the

North Fork meet from almost opposite directions, and, turning abruptly

eastward, receive Mistaya River in a sharp angle from the south, the

combined stream finding exit to the plain through the portals between

Wilson and Murchison.

Something of the trails

in these valleys I had learned from the journey to the Freshfield Group;

but beyond the Saskatchewan Forks it was a vast unknown —although Ladd

and I, from peaks near Lake Louise, had seen the far mysterious

mountains of the north and had wished to make their closer acquaintance.

It seemed a shame that these beautiful snowy summits should have no

admirers but themselves.

Following the Divide

from Bush Pass, in a northward air-line of twenty miles, one reaches

Thompson Pass, crossing the Forbes-Lyell Group en route. There is no

magic carpet equal to a map for doing such a thing; in reality it would

be extremely difficult, for the Lyell Icefield system is a large one and

the glaciers of the Lyell massif1 alone occupy

more than thirty square miles. The icefield was discovered, as were so

many other topographical features of the region, by Dr. Hector. He had

gone there in behalf of the Palliser Expedition, in 1859, the year

preceding his visit to the Freshfield Group. Encamped at Glacier Lake,

he tells us,2 “Two hours, with the aid of the

track the men had hewn, brought us to the west end of the lake, where

there is a few miles’ extent of open grassy plain, fringed with wood,

intervening between the foot of the glacier and the water’s edge.

“Reserving the ascent

of the glacier for the next day, I ascended the south side of the

valley, and found it to be composed of deep blue lime-stone, full of

iron pyrites in nodules. Start at sunrise to ascend the glacier,

accompanied by Sutherland. The other men I sent off to hunt for sheep or

deer, of which we found a few tracks.” Then follows a paragraph,

entertaining, and preserving for us one of the few instances of

superstition of Canadian Indians regarding a mountainous area: “I wished

Nimrod [Dr. Hector’s chief hunter] to go with me, but he would not

venture on the ice, but told all sorts of stories of sad disasters that

had befallen those Indians that ever did so; how that, if they did not

get lost in a crevasse, they were at least sure to be unlucky afterwards

in their hunting.

“I saw now that the

glacier I was upon was a mere extension of a great mass of ice, that

enveloped the higher mountains to the west, being supplied partly

through a narrow spout-like cascade in the upper part of the valley, and

partly by the resolidifying of the fragments of the upper Mer de Glace,

falling over a precipice several hundred feet in height, to the brink of

which it was gradually pushed forward. A longitudinal crack divides the

glacier throughout nearly its entire length, sharply defining the ice

that has squeezed through the narrow chasm, from that portion of the

glacier that has been formed from the fallen fragments, the former being

clear and pure, while the latter is fouled by much debris resting on its

surface and mixed in its substance.

“The blue pinnacles of

ice, tottering over the brink of the cliff, were very striking, and it

was the noise of these falling that we had mistaken for thunder a few

days before when many miles down the valley. On coming fairly in view of

the precipice, when about two miles from the front of the glacier, I

found, by watching the fall of these pinnacles, and observing the

interval till the crash was heard, that I was a little more than four

miles distant, so that the lower part of the glacier is about six miles

in length. After examining the surface of the glacier, and arriving at

its upper end close to the precipice, we struck off to the north side of

the valley, to ascend a peak that looked more accessible than the other.

“Here we found traces

of where a bear had been digging roots of alpine plants. We started an

old goat, and got quite close to him, but not having a gun could do him

no harm. We had a splendid view over the Mer de Glace to the south and

west, the mountain valleys being quite obliterated, and the peaks and

ridges standing out like islands through the ice mantle.”

Mount Forbes was

unnamed in those days, but Dr. Hector saw it and recognized its

pre-eminence; for he goes on to say, “The mountains to the north are

very rugged, but not so high as those to the south of the valley. In

that direction there is one peak which has a pyramidal top completely

wrapped in snow, and at least double the height of where I stood.”

Dr. Hector’s narrative

is so accurately and clearly written that we found it quite worth while

to continue our delving. We learned that, after the pioneers, alpinists

came searching for these great mountains of the north. But they too were

forced to become explorers, since information was incomplete, and, in

many cases, incorrect. Coleman, in 1892, rediscovered Fortress Lake,

and, in the following year, visited Athabaska Pass. Wilcox, in 1896,

starting from Laggan, was the first white man to journey up the North

Fork and cross to the Athabaska. Collie and his companions had come out

from England, in 1897 visiting the Freshfield region, and in 1898

discovering the Columbia Icefield itself. Habel, the German explorer, to

whom we are indebted for calling attention to the beauty of the Yoho

Valley, in 1901 made an extensive study of the western sources of the

Athabaska, penetrating to the northern base of Columbia, calling it

“Gamma.” Sir James Outram, in 1902, with the guide Christian Kaufmann,

and accompanying Collie during a part of the season, accomplished a

series of great climbs, including first-ascents of Freshfield, Forbes,

Lyell, Alexandra, Bryce, and Columbia. Reasonable enough that we, too,

should have been attracted by these stories of such an alpine

Wonderland!

It was early in the

spring when we arranged our plans. Our outfitter, of course, would be no

other than Jim Simpson, who had taken Palmer and myself to the

Freshfield Group during the season preceding. Jim was quite keen to go

again into the north-country which he knows so well. He wrote to say

that Tommy, best of cooks, would be with us again; and that one, Ulysses

La Casse—because of his broad grin more conveniently known as

“Frog”—would come as horse-wrangler. Finally, and luckiest of all, we

secured the promise of Conrad Kain, super-guide and philosopher, whose

stories have since quieted our nerves over many a day of bad weather, to

lead us up the icefield peaks.

No one, for many years,

had visited the Thompson Pass area with climbing purpose; and, as there

remained an untouched twelve-thousand-foot peak on the Columbia field,

we could scarcely be expected to control our excitement. It was July

27th when we left Lake Louise with our procession of horses. We had

quite an audience, for the start of a pack-train is a thing not seen

every day. Such a commotion! Boxes and saddles; duffle bags and pans.

Squealing horses tethered in the scrub-pine, breaking loose now and then

and galloping through the clearing, bells clanging and pack-covers

flapping. The cayuse that is being packed —how sleepily he stands, with

belly forcibly distended lest the rope be too tight; the shrewd look in

his eye as an uncovered axe touches his rump. A heave and a buck;

profanity and the operation repeated ... off at last with the horses

fighting for their place in line.

Bow Lake, where

tumbling icefalls and sparkling water afford a setting in which many an

Izaak Walton has become oblivious of his sport, was reached on the

second day. Jim has a fine camp there now; a comfortable boat, brought

in from the railroad by pack-horses, a snug boat-house on the sandy

beach, and a regular block-house of logs where one could spend the most

restful sort of vacation. We recommend it.

On the day following,

we rode through the meadows leading in gentle slope to the summit of Bow

Pass, and down the Mistaya to campground on the Wildfowl Lakes. There we

pitched our tents, the nest of a ruby-throated humming-bird above our

door, and wandered along the lake shore where we could watch the antics

of sandpiper, wheeling and darting in broken flight, and harlequin duck

diving and rippling the calm-mirrored images of jagged ridge and

ice-hung peak.

Simpson and Ladd walked

down to the lower lake to investigate a cache of provisions in a little

cabin. I went part way along the lake to photograph and sat down to

admire the majesty of Howse Peak and the wall of the northern Waputiks.

A stiff breeze was blowing, catching up the water and whirling the

surface spray up into curious, transient waterspouts six and eight feet

high over a circle twenty feet in diameter. The boys were soon back,

reporting that a wolverene—the nightmare of winter trap-lines—had got

into the cabin, and made things the worse for his visitation.

Our next day of travel

was a delight. Between the lakes Mistaya River is forded, trail leading

to the Forks of the North Saskatchewan. We pass through Pyramid Camp,

where we had stopped a year before, our blaze still legible on the big

tree under which we had slept. The river foams and boils in a misty

canyon, far below; towers of Murchison rise across the valley like

shattered cathedrals; pack-horses are splashing through pools and

sloughs whose borders are riotous in flower colours. The trail is cut

and broken by turbulent glacial brooks, with soaring ice-clad peaks

above. An eagle soars from the cliff shadows, into blue space, guiding

us to the Saskatchewan.

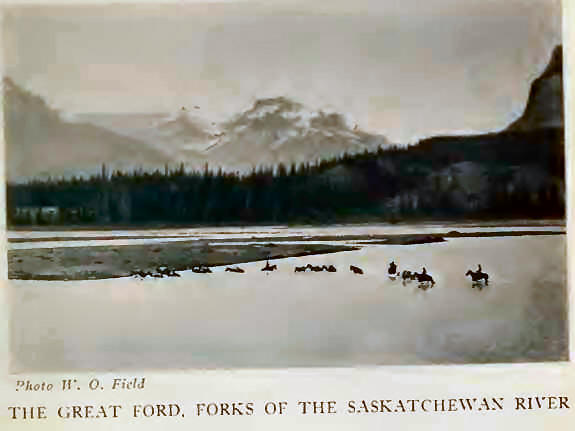

At the Forks, instead

of turning up Howse River, the entrance to the Freshfield Group, we

crossed the long ford and camped on the far bank below Mount Wilson. If

one is unlucky, at high water there will be swimming and wet packs. The

river flows between Murchison and Wilson, past the Kootenay Plain and,

continuing as Nelson River, connects Lake Winnipeg with far distant

Hudson Bay. Here, however, it is broken by gravel-bars into shallow

rapids, through which the horses struggle, while their riders make

futile attempts to remain dry-shod. Camp is splendidly situated on a

terrace, at the junction of the North Fork, Howse and Mistaya Rivers,

where in the long-ago the Indians came to tan and cure hides after their

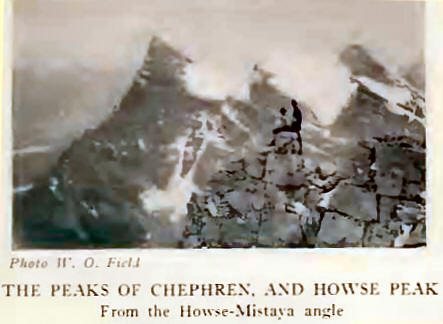

hunting trips. The panorama is one of great beauty, strangely suggestive

of the Oberland peaks from Grin-delwald—sky-soaring Chephren with its

pure white snow-saddle, ice-hung Kaufmann Peaks, and the rockwall of

Sarbach, massed in the Howse-Mistaya angle. A glimpse of the Lyell

Icefield through the gap of Glacier Lake, and the spire of Forbes, add

to a scene whose foreground is a river, lighted by the afternoon sun,

with horses grazing on the flats, and smoke rising through gnarled and

ancient trees.

In his journal, under

date of February 8, 1811, Alexander Henry (the younger) makes the

following entry: . . we came to the forks, where the river spread to

about half a mile wide, free from islands; but as usual in such places,

the bed was choked with bars of sand and gravel. Here a branch of the

Saskatchewan comes in from the N. opposite a smaller branch from the S.;

both appear contracted, winding their courses through mountains. The

main channel, up which our course lay, is still wide, and comes from the

W. At the junction of these forks we had a grand view of the mountains,

more elevated and craggy than any we had before seen. The upper parts of

some of them are curiously formed, some closely resemble citadels, round

towers, and pinnacles rising to a great height, with perpendicular

summits, so steep that no human being could ascend them. Some of the

highest remained all day enveloped in clouds, which were not dispersed

for several hours after the wind arose, and even then hovered upon the

summits as if loath to leave, until torn away by the violence of the

wind, which increased to a gale from the W. Upon the top of a mountain

N. W. of us, whose summit appeared level, I observed an immense field of

snow, of which a part seemed lately to have separated and fallen down.

This frequently happens during winter, when vast quantities of snow

accumulate till the mass projects beyond the rocks and then gives way.

The noise occasioned by the fall of such a body of snow equals an

explosion of thunder, and the avalanche sweeps away everything movable

in its course to the valleys. On the sides of some of the mountains S.

of us, where the rays of the sun never reach, are vast beds of eternal

snow, or, more properly, bodies of eternal ice, their bluish color

plainly distinguishing them from the snows of this season; some parts

have recently given way and fallen into the valleys, while the remainder

presents a perpendicular face of ice in strata of different thicknesses.

Here we saw the tracks of several herds of buffalo, which had crossed

the river.” —“New Light on the Early History of the greater North-West,”

Henry Thompson Journals, 1789-1814, Elliott Coues (F. P. Harper, New

York, 1897), Vol. II, p. 689.

The Forbes-Lyell Group

of mountains is separated into southern and northern divisions by the

Mons and Lyell Icefields, lying on the Continental Divide. The chief

peaks of the southern area are Forbes (11,902 feet), east of the Divide,

and Bush Mountain—Rostrum Peak (10,770 feet), and Icefall Peak (10,420

feet)—in British Columbia. Peaks of the Divide, north of Bush Pass,

Cambrai (10,380 feet), Messines (10,290 feet), and Mons (10,114 feet),

show what part the late war played in the nomenclature of the Northwest.

The northern division

extends from Mount Lyell to Thompson Pass (6511 feet), in the splendid

range encircling the head of Alexandra River. Lyell possesses five

peaks, all above 11,000 feet, from the central one of which the Divide

continues northward over Farbus, Oppy, and Douai, and rises to the

abrupt, snowy summits of Alexandra—11,214 feet, and 10,990 feet—whence

it crosses Fresnoy (10,730 feet), Spring Rice (10,745 feet), and

descends to Thompson Pass from the summit of Watchman Peak.

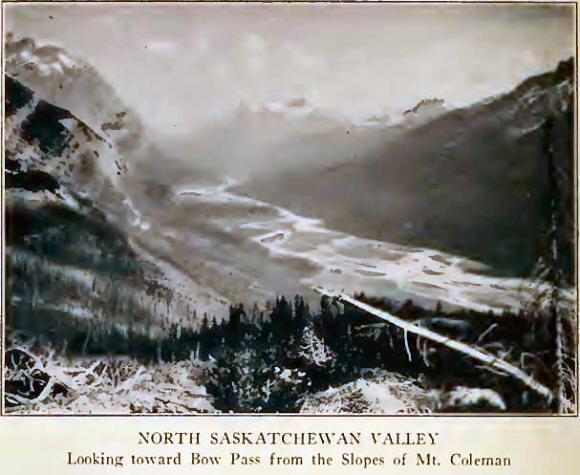

Morning came; daffodil

glow preceding a succession of delicate colours, and leading us up the

North Fork Valley. Bars of sunlight relieve the shadowy recesses of

primeval forest—cottonwood, poplar, and cedar—through which winds the

trail. Close to the cliffs of Mount Wilson, meandering streams,

suggesting lines of a jig-saw puzzle, gleam through the meadows. Tiny

fish dart in the shallows; and all the toads seem to be amphibious,

hopping into the water as our horses pass. Mount Saskatchewan, mirrored

in many a quiet pool, stands guardian of the entrance to Alexandra

River.

“Graveyard,“ because of

ancient hunting relics which adorn it, is the name given to the camping

place opposite the mouth of Alexandra River. A bit of buffalo skull,

white and friable, recalls the days when these huge animals ranged even

into the remote valleys of the north. Pinto Pass, with an old Indian

trail leading over the Cline4 River, may be reached in a few hours; Ladd

and I strolled out above it to the bench-land below Mount Coleman for a

far-reaching view of the Saskatchewan Valley. We sat down among the

forget-me-nots; Bow Pass could still be seen, a dim grey-blue saddle on

the southern skyline. We looked into Alexandra Valley where brilliant

light outlined the distant range. The sun was setting behind the

outlying pinnacles of Mount Saskatchewan—antique towers and

air-castles—while purple shadows lengthened in the gorge below, and

against this glorious background we watched three sheep, in silhouette

row, walk up a nearby ridge and disappear.

With the exception of a

few travellers and Indian hunters, there have been but few visitors to

the valley of Alexandra River. Locally known as the “West Branch,” the

first white men to gain even a partial view of it were Wilcox3

and Barrett who in 1896, en route to Fortress Lake, ascended a spur of

Mount Saskatchewan and looked up the river to its bend.

Based on information

from Tom Wilson, of Banff, that there was an Indian trail across the

pass at the valley-head, Mr. C. S. Thompson, an enthusiastic

mountaineer, in 1900, travelled as far as the pass now bearing his name.

He took one packer with him, and although no climbing was attempted

because of bad weather prevailing, they explored the pass and visited

the northern glaciers of Lyell.6

During the summer of

1900, Messrs. Collie, Spencer and Stutfield attempted to penetrate to

the Columbia Icefield by way of the Bush Valley and the western slope of

the mountains. C. S. Thompson at the same time went north by the

Saskatchewan Valley, hoping to locate Collie’s party by way of the pass

at the head of the “West Branch.”

The hardship of

pack-train travel on the British Columbia side of the Divide is

amusingly set forth in a letter, dated Dec. 31, 1902, from Collie’s

outfitter, Fred Stephens, to Mr. Walter D. Wilcox:

“Better late than Never

so as i Promised 3Tou; would Rite and tell you something of our Bush

River trip i will just give you a Pointer to Pass it By. We left Donald

and followed an old trail which Led through a Dence forest to the mouth

of Bush River. We apparently followed the Columbia but was out of sight

of it most of the time; never saw such undergrowth mud and wet, with

mosquitoes that would stop a syclone, the poor Englishmen looked like

Plum Puddings walking around with their faces swoolen up to twice their

Natural size. Well we wanted to get to the head of the Bush River but

found it in high water to be impossible to follow up the Bank. We took

the trail back 6 miles then climbed up over a mountain with the outfit

and struck the River 7 or 8 miles up. It was raining 7 days out of 6, to

make it more Pleasant. The Pack horses got covered with Brittish

Columbia mold, the oat meal soured, the hard tack swelled up so we had

to Pack our saddle horses. The wood would not burn and a few more things

went Rong. We finally got up the River far enough so it commenced to get

deep and the valley was Narrow and filled with Burnt fallen timber. We

There is still a faint

trail, with many crossings of the stream which divides and wanders

between little green islands, where birds hide and disclose their

presence only when one approaches closely. Alexandra and its tumbling

glacier-falls loomed ahead. Several deer bounded away when they got wind

of the horses. Little drab buffalo-birds followed us; friendly fellows

who like nothing better than a ride on the back of a cayuse. There are

many game tracks, but in the heat of the day the larger animals—deer,

moose, and sheep —are high up near timber-line where cooler breezes

drive off the flies. Just as the Freshfield area was the home of big

goats, so this and neighboring valleys form the territory of the sheep;

for sheep and goat are on unfriendly terms and do not range together.

We passed by Camp

Content, where Outram had stopped years before, and, crossing an angle

of the nearly drouned Harry Long because he could not ride a raft of

water soaked logs. We found it impossible to follow up the valley to the

foot of Mt. Bryce and Columbia so we took to the hills and camped 7000

above sea Level. Here it snowed for 4 days and the wind blowed so we had

to tie down the Pack Saddles to keep them in camp. I suppose this would

be Delightfull to you But somehow it dont catch me. This was as far as

we got although i could go mutch farther but the weather was so cloudy

that it was useless to go farther. Here we turned and came Back to

Donald. I think we were about Due west of the west Branch whitch comes

into the west fork of the Saskatchewan.

“I will wind this

interesting slip to a close; have no Doubt you would find this a very

interesting country to go to as the mountains are verry high and craggy.

The whole country is verry Rough and the weather in July will freeze a

kyote so I am sure you would call it Grand.” river, placed our tents

close to the Alexandra Glaciers, naming our stopping place—the reason

was obvious— “Last Grass Camp.” Mount Oppy (10,940 feet), with its

gabled ice-crest, rises with Alexandra above this spot, with the

northern Lyell basin close at hand. It was our intention to attack this

basin in the hope of attaining the Lyell-Farbus col and the unclimbed

Divide peak of Lyell (No. 3; 11,495 feet), just equal in height to the

central peak ascended by Outram. There also one might traverse the arete

of Farbus (10,550 feet), and across a steep little ice-col reach Mount

Oppy itself, peaks well guarded by icefalls above the Alexandra

Glaciers.

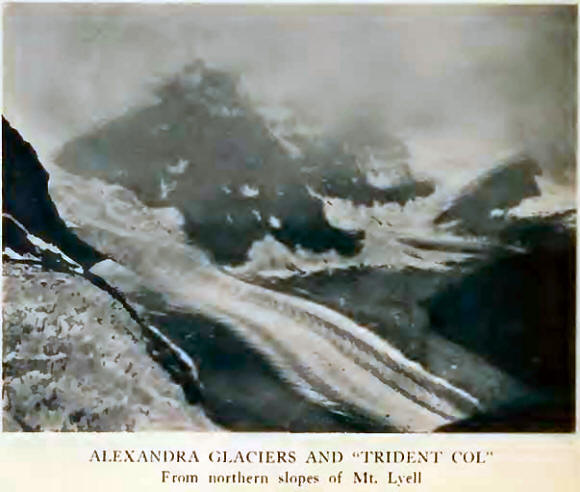

But weather was ever

unkind. We visited the glaciers, scarcely half a mile distant; enormous,

with flat tongues spreading below broken seracs so placed that one can

only with difficulty reach the upper snows. The western Alexandra

Glacier is conspicuous with its regular, parabolic dirt-bands,

differentiating the seasonal variation between winter and summer snows.4

On our first walk over the ice, a little shower passed, followed by an

entrancing double rainbow which arched from the ice-tongue to our camp

in the woods below.

Next day the peaks were

again shrouded in mist. It was July 4th, and we ascended, in three

hours, into the northern Lyell basin. Crevasses and the icefall of the

eastern Alexandra Glacier soon forced us to the moraine, a direct ascent

to which is made unpleasant by muddy cliff and running water. By a

little fire, kindled on an upper meadow, we sat and watched for

momentary glimpses into the upper ice-world as the snow-tops played

hide-and-seek in the fog. So many times from the viewpoints above Lake

Louise we had seen the triple-headed snow-mountain clear, against an

azure northern background; now to be on its very slopes and find it

hidden. Still it was not an unpleasant place to be, there beside our

smouldering fire. Although the heights were often invisible, we could

always gaze downward on those marvelous glaciers. The masses of ice were

softened here and there by the interposition of thin vapors, drifting

back and forth; towers and pinnacles of ice seemed on the verge of

splitting and crumbling; sea-green arches, transparent as our

finger-tips seem when held before a strong light, were all luminous with

the pale yellow glow that came through a distant snow-saddle beyond Rice

Glacier. Then, as we descended, rain drenched us. But a roaring fire at

camp, and a bit of bear-steak that Simpson brought in—I think he said he

found it growing on a tree—made us quickly forget the weather.

A few days later we

rode to Thompson Pass. It had cleared off, and we followed the trail up

Castleguard River—the name given to the stream above the Alexandra

angle—and through dense forest to the broad grassy levels leading to the

summit lakes. Watchman Peak is charmingly reflected in the lower lake,

while from the pass summit, below Spring Rice, we could look far into

the gloomy depths of Bush Valley with the unbroken wall of Mount Bryce

descending into it. This western country is wild in its appearance and

looks nearly impossible for horses.

It must have been about

this time that Jim, apropos of nothing in particular, remarked that his

birthday was about to recur. Tommy and I made secret plans. When the day

arrived, Tommy concocted a gigantic doughnut, liberally powdered with

sugar and mounted on a pedestal of heather. We stood the candle from our

folding-lantern in the centre and the result was almost artistic. At

lunch-time it was brought in with all ceremony and presented to “Chief

Nashan”—for Jim is known as the Wolverene among the Stoney Indians,

because of his uncanny ability as a hunter. Jim was much surprised; but

we were still more so, when he confessed that although the date was

right he had been a whole month short on time! Still we had had our fun

and the monotony of a day of showers was broken. After all, time on the

trail is an impossible thing to keep track of. |