|

By Rev. Alexander

Sutherland, D.D.

IT is often said that

the Church of Christ is essentially missionary. The saying is trite but

true. The great purpose for which the Church is organized is to “preach

the Gospel to every creature,” and its mission is fulfilled only in so

far as this is done. But, as commonly used, the saying is the

recognition of a principle rather than the statement of a fact. It is

clearly perceived that the Church ought to be intensely missionary in

spirit and practice, and this view is often pressed as an argument to

quicken flagging zeal and to revive, if possible, the apostolic spirit

in the Church of to-day. Compared with apostolic times, missionary zeal

and enterprise is yet below high-water mark ; but compared with the

state of affairs one hundred years ago, it cannot be said that the

former times were better than these. Within the century—indeed, within

the last two or three decades—there has bpen a marvellous revival of the

missionary spirit. The sleep of the Church has been broken. Her dormant

energies have been aroused. An aggressive policy has been declared.

Responsibility, even to the measure of a world-wide evangelism, is

freely acknowledged, and the disposition to consecrate men and money on

the altar of missionary sacrifice grows apace. All this gives token of a

coming day in the not distant future when it may be affirmed without

qualification that the Church—in fact as well as in profession—is

essentially missionary.

It may be claimed,

without boasting or exaggeration, that Methodism has not only

contributed somewhat to the revival of the missionary spirit, but has

been, under God, a chief factor in promoting it. The place of her

nativity was hard by the missionary altar, and a spirit. of intense

evangelism gave the first impluse to her work. Born anew amid the

fervours of a second Pentecost, her first preachers were men baptized

with the tongues of flame, symbol of a comprehensive evangelism that

found expression in the motto of her human leader, “ The World is my

Parish.” In the spirit of that motto Methodism has lived and laboured,

and after the lapse of more than a hundred years the primitive impulse

is still unspent. Wherever the Banner of the Cross is unfurled,

Methodist missionaries are found in the van of the advancing hosts, and

the battle cry of the legions is “The World for Christ.”

The beginnings of

Methodism in Canada reveal the same providential features that marked

its rise in other lands. Here, as elsewhere, it was the child of

Providence. No elaborate plans were formulated in advance. No

forecastings of human wisdom marked out the lines of development. But

men who had felt the constraining power of the love of Christ, and to

whom the injunction to disciple all nations came with the force of a

divine mandate, went forth at the call of God, exhorting men everywhere

to repent and believe the Gospel. Out of that flame of missionary zeal

sprang the Methodist Church of this country; and if the missionary cause

to-day is dear to the hearts of her people, it is but the legitimate

outcome of the circumstances in which she had her birth. Methodism is a

missionary Church, or she is nothing. To lose her missionary spirit is

to be recreant to the great purpose for which God raised her up. Nor can

she give to missions a secondary place in her system of operations

without being false to her traditions and to her heaven-appointed work.

While Methodism in

Canada was, from the very first, missionary in spirit and aims, what may

be called organized missionary effort did not begin till 1824. In that

year a Missionary Society was formed. It was a bold movement, such as

could have been inaugurated only by heaven-inspired men. Upper Canada

(at that time ecclesiastically distinct from Lower Canada) was just

beginning to emerge from its wilderness condition. Settlements were few

and, for the most part, wide asunder. Population was sparse, and the

people were poor. Moreover, Methodism had not yet emerged from the

position of a despised sect, and prejudice was increased by the fact

that it was under foreign jurisdiction. Such a combination of

unfavourable circumstances might well have daunted ordinary men, and led

to a postponement of any effort to organize for aggressive missionary

work. “But there were giants in the earth in those days,” whose faith

and courage were equal to every emergency ; men who could read history

in the germ, and forecast results when “ the wilderness and the solitary

place” should become “glad,” and “the desert” should “ rejoice, and

blossom as the rose.” As yet it was early spring-time, and sowing had

only just begun; but from freshly-opened furrows and scattered seed

those men were able to foretell both the kind and the measure of the

harvest when falling showers and shining suns should ripen and mature

the grain. In that faith they planned and ‘ laboured. They did not

despise the day of small things, but with faith in the “ incorruptible

seed,” they planted and watered, leaving it to God to give the increase.

In this, as in other cases, wisdom was justified of her children. When

the Missionary Society was organized, in 1824, two or three men were

trying to reach some of the scattered bands of Indians; the income of

the Society the first year was only about $140, and the field of

operation was confined to what was then known as Upper Canada. To-day

the missionary force represents a little army of more than a thousand

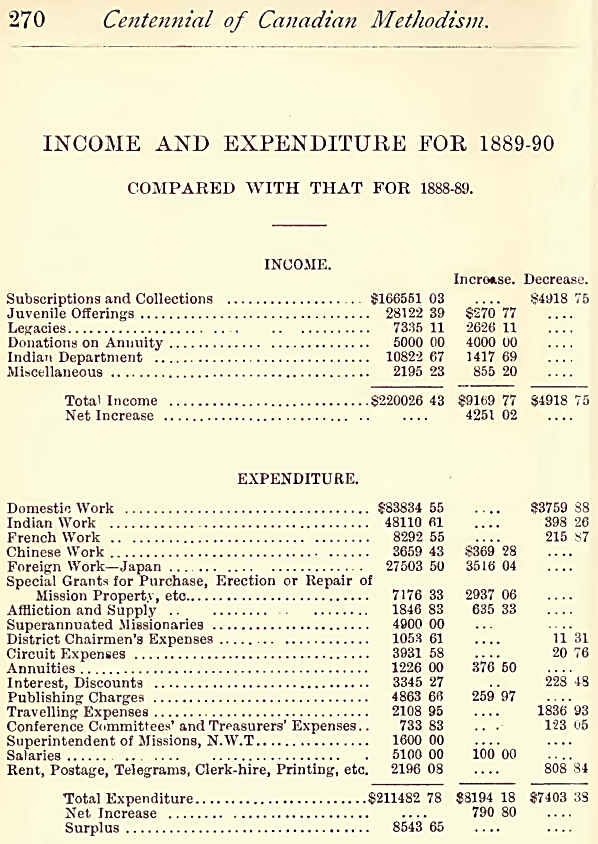

persons (including the wives of missionaries). The income exceeds

$220,000, while the field covers half a continent, and extends into “the

regions beyond.”

The development of the

missionary idea in the Methodist Church in Canada has been influenced by

epochs in her history, marking changes in her ecclesiastical polity. In

1828, the Canadian Societies were severed from the jurisdiction of the

Church in the United States, and formed into an independent branch of

Methodism, with its own conference and government. In 1832 a union was

formed with the English Wesleyan Conference, whereby the field of

operation was extended; but, unfortunately, this movement was followed

by a division in the Church itself, which continued until the great

union movement of 1883 obliterated all lines of separation and reunited

the divided family. Again, in 1840, the union with the English Wesleyans

was broken, and for seven years the two societies waged a rival warfare,

which was by no means favourable to the growth of true missionary

spirit. This breach was healed in 1847, and from that time onward the

missionary work of the Church steadily developed, embracing the Wesleyan

Indian Missions in the

far north, establishing a new mission in British Columbia, and extending

the home work in all directions throughout the old Provinces of Upper

and Lower Canada.

The year 1873 marks a

distinct epoch in the history of missions in connection with Canadian

Methodism. In that year the bold step, as some considered it, was taken

of founding a distinctively foreign mission, and many indications

pointed to Japan as a promising field. The wisdom of the step was

doubted by many, who thought the home work sufficiently extensive to

absorb the energies and liberality of the entire Church. Viewed from the

standpoint of mere human prudence, the objectors were right. The home

missionaries were struggling along with very inadequate stipends; many

Indian tribes were still unreached; the calls from new settlements in

our own country were loud and frequent, and the vast French population

of the Province of Quebec was scarcely touched by Methodist agencies.

Under such circumstances, it is not to be wondered at that some were

inclined to say : “We have here only five barley loaves and two small

fishes, but what are they among so many % ” But there were others who

remembered the lesson of the “ twelve baskets of fragments ” taken up

after five thousand men, besides women and children, had been fed ; and

these said : “ Let us have faith in God; let us bring our little at His

command, and with Christ’s consecrating blessing our little will

multiply until there will be enough to feed the hungry multitude, and

the Church shall be recompensed far beyond the measure of what it gives

away.” And so in faith and prayer the forward movement was inaugurated,

and a mission planted in Japan which, from the very beginning, has

shared largely in blessings from on high. Nor did the home missions

suffer ‘because of this new departure, for the missionary spirit thus

revived in the Church was followed by a corresponding liberality, and

the increased contributions more than sufficed to meet the increased

expenditure.

The next development

affecting the polity and work of the Church occurred in 1874, when the

Wesleyan Methodist Church, the Methodist New Connexion Church, and the

Wesleyan Church of Eastern British America, united in' one body under

the name of The Methodist Church in Canada. This union extended the Home

Missions of the Church by consolidating the forces east and west, thus

covering the whole extent of the Canadian Dominion, and embracing in

addition, Newfoundland and the Bermudas. This arrangement involved the

peaceful separation of the three churches named from the jurisdiction of

the Wesleyan body in England, and the relinquishment, after a few years,

of certain missionary subsidies which they had been in the habit of

receiving from the parent treasuries. The loss of these subsidies and

the increased expenditure in consequence of unavoidable readjustments of

the work, caused temporary embarrassment and the accumulation of a

somewhat serious debt; but an appeal to the Church met with so liberal a

response, that the debt was extinguished without reducing the regular

income, and the work went on as before. It was felt, however, that, for

a time at least, the duty of the Church would lie in the direction of

consolidation rather than expansion, and hence for several years no new

movement was made beyond the prudent enlargement of fields already

occupied.

The missionary spirit

which for years had been growing in the Methodist Church, found a new

outlet in 1880 in the organization of the Woman’s Missionary Society. In

June of that year a number of ladies met in the parlours of the

Centenary Church, Hamilton, at the invitation of the General Missionary

Secretary, when the project was carefully considered and the conclusion

reached to organize forthwith. That afternoon meeting marks the

beginning of what promises to become one of the most potent forces in

connection with the mission work of the Methodist Church. Nor can a

thoughtful observer fail to see how Divine Providence controlled the

time as well as the circumstances. The Union movement, which culminated

in 1883, was first beginning to be discussed. Four distinct Churches

were proposing to unite, but whether it would be possible so to

amalgamate their varied interests as to make of the four one new Church,

was a problem that remained to be solved. In the accomplishment of this

difficult task, the mission work of the Church was a prime factor, for

it served by its magnitude and importance to turn the attention of

ministers and people from old differences and even antagonisms, and to

fix it upon a common object. What the work of the present Society did

for one part of the Church, the woman’s movement did for another. Just

at the right moment Providence gave the signal, and the godly and

devoted women of Methodism in all the uniting Churches joined hands in

an earnest effort to carry the Gospel to the women and children of

heathendom, and in that effort they mightily aided to consolidate the

work at home. The constitution for a Connexional Society was not adopted

till 1881, but in the nine years following, the income has risen from

$2,916.78 in 1881-2, to $25,560.76 in 1889-90. At the present time

seventeen lady missionaries are in the employ of the Society, and

decision has been reached to send pioneers to China in connection with

the onward movement of the parent Society.

It was thought at one

time that the union of 1874 would have included all the Methodist bodies

in Canada, as all were represented at a preliminary meeting held in

Toronto. This expectation was not realized, owing to the retirement of

several of the bodies from subsequent negotiations ; but the discussions

which took place, no less than the beneficial results of the union

itself, created a desire for union on a more extended scale. This desire

was greatly strengthened by the famous Methodist Ecumenical Conference,

which met in London in 1881, and at the next General Conference of the

Methodist Church in Canada distinct proposals were presented, and

negotiations initiated with other Methodist bodies. It is not necessary

in this paper to present a detailed history of the movement. Suffice it

to say that, in 1883, a union embracing the Methodist, Methodist

Episcopal, Primitive Methodist and Bible Christian Churches in Canada,

was consummated, and the impressive spectacle presented of a

consolidated Methodism—one in faith, in discipline and usages—with a

field of home operations extending from Newfoundland to Vancouver, and

from the international boundary to the Arctic circle, 'i he union did

not actually extend the area formerly embraced by the uniting Churches,

but it involved extensive readjustments of the work, increased greatly

the number of workers, and, for a time, necessitated increased

expenditure. The income, however, showed corresponding growth, and

although stipends remained at low-water mark, no retrograde step was

taken.

As at present

organized, the mission work of the Methodist Church embraces five

departments, namely :—Domestic, Indian, French, Chinese and Foregn. All

these are under the supervision of one Board, and are supported by one

fund. Each department, in view of its importance, claims a separate

reference.

I. THE DOMESTIC OR HOME

WORK.

Under this head is

included all Methodist Missions to English-speaking people throughout

the Dominion, in Newfoundland and the Bermudas. From the very inception

of missionary operations, the duty of carrying the Gospel and its

ordinances to the settlers in every part of the country, has been fully

recognized and faithfully performed. Indeed, this was the work to which

the Church set herself at the beginning of the century, before

missionary work, in the more extended sense, had been thought of. At

that time the population was sparse and scattered. Of home comforts

there was little, and of wealth there was none, but the tireless

itinerant, unmoved by any thought of gain or temporal reward, traversed

the wilderness of Ontario and of the Maritime .Provinces, often guided

only by a “blaze” on the trees or by the sound of the woodman’s axe, and

in rough new school-houses, in the cabins of frontier settlers, or

beneath shady trees on some improvised camp-ground, proclaimed the

message of reconciling mercy to guilty men. No wonder that their message

was listened to with eagerness, and often embraced with rapture. Many of

the settlers had, in early life, enjoyed religious privileges in lands

far away, and these welcomed again the glad sound when heard in their

new homes; while others who, under more favourable circumstances, had

turned a deaf ear to the Gospel message, were touched with unwonted

tenderness as they listened to the fervid appeals of some itinerant

preacher amid the forest solitudes. Thus, by night and by day, was , the

seed scattered which, since then, has ripened into a golden harvest. And

if a time shall ever come when a truthful history of the

English-speaking Provinces of the Canadian Dominion shall be written,

the historian, as he recounts and analyzes the various forces that have

contributed to make the inhabitants of these Provinces the most

intelligent, moral, prosperous and happy people beneath the sun, he will

give foremost place to the work of the old saddle-bag itinerants who

traversed the country when it was comparatively a wilderness, educating

the people in that reverence for the Word and worship of God which is

alike the foundation of a pure morality and the safeguard of human

freedom.

When the Missionary

Society was organized, and its income began to grow, the Church was in a

position to carry on its home work more systematically, and to extend

that work far beyond its original limits. The constant changes taking

place in the status of these Home Fields, as they rise from the

condition of dependent missions to that of independent circuits, renders

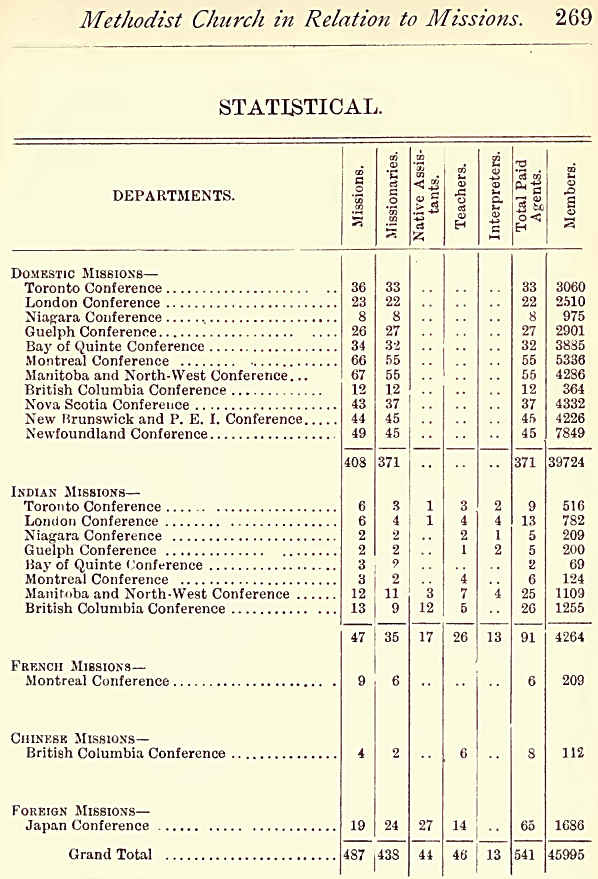

any comprehensive numerical statement impossible. Suffice it to say,

that at the present time there are 408 Home Missions, with 371

missionaries, and an aggregate membership of 39,724, and on these is

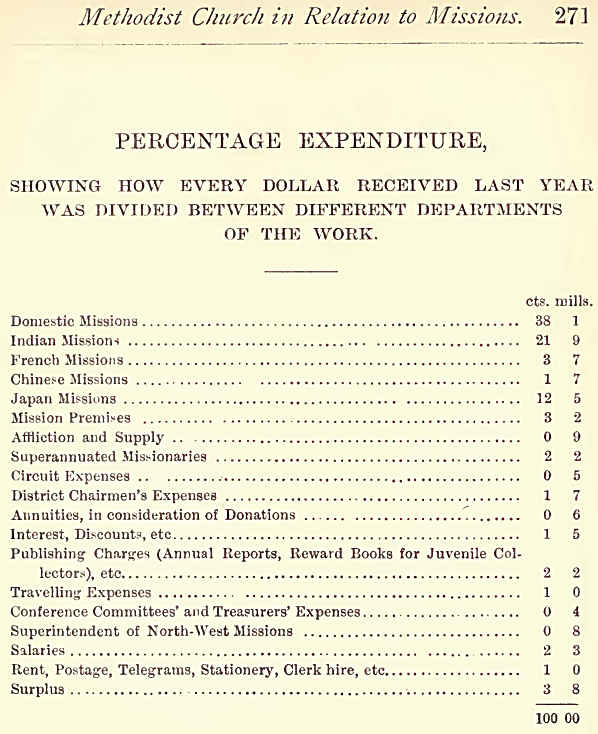

expended about 42 J per cent, of the Society’s income. The outlook for

this department is hopeful and inspiring. The opening up of our

magnificent North-West, with a teeming population in prospect, presents

a grand field for remunerative mission work which the Church will do

well to improve, and she needs no higher aim than to repeat in the New

Territories the salient features of the religious history of Ontario.

II. THE INDIAN WORK.

This department of

mission work has always shared largely in the sympathy of the Church and

of the Mission Board ; and although it has made but little return, in

kind, for the large sums expended, yet in spiritual results the Church

has been amply repaid. In British Columbia, as the direct result of

missionary effort, tribal wars have entirely ceased, heathen villages

have been transformed into Christian communities, and the gross

immoralities of the dance and the “potlatch” have given place to

assemblies for Christian instruction and sacred song. In the North-West

similar results have been achieved, and it has been demonstrated that

the advancement of the native tribes in intelligence, in morality, in

loyalty, in the arts and refinements of civilized life, keeps even step

with the progress of Christian missions. Very significant is the fact

that during the revolt among certain Indians and Half-breeds in the

North-West, notone member or adherent of the Methodist Church among the

Indians was implicated in the disturbances ; and it is now generally

acknowledged that the unswerving loyalty of the Christian

Indians—notably of Chief Pakan and his people at Whitefish

Lake—contributed more than any other circumstance to prevent a general

uprising of the Cree nation. In Ontario, results in recent years have

not been so marked as in British Columbia and the North-West, owing to

the fact that most of the bands are now in a fairly civilized state, and

there is but little in outward circumstances to distinguish the work

from that among the whites. A.n important feature of the Indian work at

the present time is the establishment of Industrial Institutes, where

Indian youth are instructed in various forms of industry suited to their

age and sex. The Institute at Muncey, Ont., has over eighty pupils, and

is in process of enlargement to accommo-, date 120 ; in Manitoba and at

Reed Deer two Institutes are in process of erection ; an Orphanage and

Training-school has been in operation for some time at Morley; and a

Boarding-school at Chilliwhack, and a Girls’ Home at Port Simpson, are

under the control of the Woman’s Missionary Society. Statistics of the

Indian work for 1890 give the following results :—Missions, 47 ;

missionaries, 35 ; native assistants, 17; teachers, 26; interpreters,

13; members, 4,264. The expenditure for the same year amounted to about

23 per cent, of the Society’s income.

III. THE FRENCH WORK.

In the Province of

Quebec there is a French-speaking population of a million and a quarter,

and these, with the exception of a few thousands, are adherents of the

most solid, thoroughly-organized and aggressive type of Romanism to be

found in all the world. The Church is virtually endowed, can collect its

tithes and levy its church-building rates by law. Education is

controlled by the Bishops, and the whole machinery is used to maintain

the use of the French language and inculcate a French national spirit.

Evangelical truth is a thing almost unknown. Such a population in the

heart of the Dominion, under such control, is a standing menace to

representative government and free institutions, and this consideration,

no less than a sincere desire for the spiritual enlightenment of the

people, has led the various Protestant Churches to make some effort to

spread the Gospel among them. So far as Methodist Missions are

concerned, numerical results have been small, and the missions do not

present features as encouraging as are to be found in other departments.

But it should be borne in mind that the difficulties to be surmounted

are greater than in any other field, and that there are causes for the

comparatively small numerical increase which do not exist elsewhere.

Neither in the Domestic, the Indian, or even i he Foreign work do civil

or social disabilities follow a profession of faith in Christ; but in

the Province of Quebec a renunciation of Romanism is the signal for a

series of petty persecutions, and a degree of civil and social

ostracism, which many have not the nerve to endure, and which usually

results in their emigration from the Province. The difficulty of

reaching the people by direct evangelistic effort, led the Missionary

Board to adopt the policy of extending its educational work. In

pursuance of this policy a site was secured in a western suburb of

Montreal, and a building erected capable of accommodating 100 resident

pupils. About seventy pupils are already in attendance, and the future

is bright with promise. The amount expended on the French work,

including the Institute, is only about 3f per cent, of the Society’s

income.

IV. THE CHINESE WORK.

During the past quarter

of a century vast numbers of Chinese have landed on the Pacific Coast of

the American continent, of these not a few have found temporary homes in

British Columbia. At the time when the Rev. William Pollard had charge

of the British Columbia District some attempt was made to reach the

Chinese by establishing a school among them in Victoria, but after a few

years the enterprise was abandoned. In 1884, Mr. John Dillon, a merchant

of Montreal, visited British Columbia on business. His heart was stirred

by the spiritually destitute condition of the Chinese, especially in

Victoria, and he at once wrote to a member of the Board of Missions

inquiring if something could not be done. The matter was considered at

the next Board meeting, and it was decided to open a mission in Victoria

as soon as a suitable agent could be found. In the following spring,

1885, by a remarkable chain of providences, the way was fully opened,

and a mission begun which has since extended to other places in the

Province, and has been fruitful of good results. Commodious mission

buildings have been erected in Victoria and Vancouver, schools

established in both these cities and in New Westminster, many converts

have been received by baptism, and the foundation of a spiritual church

laid among these strangers “ from the land of Sinim,” which gives

promise of permanence and growth. A valuable adjunct is found in the

Chinese Girls’ Rescue Home, established in Victoria, and now managed by

the Woman’s Missionary Society. At the present writing the statistics of

the Chinese Mission are :—Missions, 3 ; missionaries, 3 ; teachers, 6;

members, 112.

V. THE FOREIGN WORK.

The most conspicuous

and decided onward movement of the Methodist Church on missionary lines

took place when it was decided to open a mission in Japan. But the faith

and courage of those who urged the venture have been fully vindicated by

the results. Since the inception of the work in 1873, its growth has

been steady and permanent, while the reflex influence upon the Church at

home has been of the most beneficial kind. The missionary spirit has

been greatly intensified, liberality has increased, and the Church is

looking for new fields and wider conquests. In 1889 it was found that

the growth of the work in Japan had been such as to necessitate

reorganization, with an increased measure of autonomy. Accordingly an

Annual Conference was formed, which now embraces four districts, with 19

distinct fields, besides numerous outposts. In Tokyo there is an academy

for young men, and a theological school for the training of native

candidates for the ministry; while the Woman’s Missionary Society

maintains flourishing schools for girls in Tokyo, Shizuoka and Kofu.

General statistics of the Japan' work are as follows:—Missions, 19;

missionaries, 24; native evangelists, 27 ; teachers, 14; members, 1,686.

This brief statement

respecting the foreign work of the Church would be imperfect without

some reference to the action of last year, looking to the establishment

of a new foreign mission in China. For several years leading men in the

Church had been asking if the time had not arrived when the Church

should survey the vast field of heathendom with a view of extending the

work “ into the regions beyond.” The suggestion took practical shape at

the General Conference of 1890, when the project of a new foreign

mission was favourably commended to the General Board of Missions, with

power to take such action as might seem advisable. When the question

came up in the General Board, it became evident that the suggestion was

not premature. With practical unanimity the Board affirmed the

desirableness of at once occupying new ground, and as a remarkable

series of providences seemed to point toward China, the Committee of

Finance was authorized to take all necessary steps to give effect to the

decision of the Board. It may be regarded as a settled matter that

during the present summer the vanguard of our missionary army will enter

the Flowery Kingdom.

Enough has now been

said to show that the Methodist Church of Canada, in its origin, history

and traditions, is “essentially missionary;” that its providential

mission, in co-operation with other branches of Methodism, is to “spread

scriptural holiness over the world.” If the spirit of this mission is

maintained her career will be one of ever-widening conquest. If it is

suffered to decline, Ichabod will be written upon her ruined walls.

For purposes of

reference the following tables will be found useful:—

|