|

This is the City of Winnipeg. Its growth

has been wonderful. It is the highwater mark of Canadian enterprise. Its

chief thoroughfare, with asphalt pavement, as it runs southward and

approaches the Assiniboine River, has a broad street diverging at right

angles from it to the West. This is Broadway, a most commodious avenue

with four boulevards neatly kept, and four lines of fine young Elm

trees. It represents to us "Unter den Linden" of Berlin, the German

Capital.

The wide business thoroughfare Main

Street, where it reaches the Assiniboine River, looks out upon a stream,

so called from the wild Assiniboine tribe whose northern limit it was,

and whose name implies the "Sioux" of the Stony Lake. The Assiniboine

River is as large as the Tiber

at Rome, and the color of the water justifies its being compared with

the "Yellow Tiber."

The Assiniboine falls into the Red River,

a larger stream, also with tawny-colored water. The point of union of

these two rivers was long ago called by the French voyageurs "Les

Fourches," which we have translated into "The Forks."

One morning nearly forty years ago, the

writer wandered eastward toward Red River, from Main Street, down what

is now called Lombard Street. Here not far from the bank of the Red

River, stood a wooden house, then of the better class, but now left far

behind by the brick and stone and steel structures of modern Winnipeg.

The house still stands a stained and

battered memorial of a past generation. But on this October morning, of

an Indian summer day, the air was so soft, that it seemed to smell

wooingly here, and through the gentle haze, was to be seen sitting on

his verandah, the patriarch of the village, who was as well the genius

of the place.

The old man had a fine gray head with the

locks very thin, and with his form, not tall but broad and comfortable

to look upon, he occupied an easy chair.

The writer was then quite a young

man freshfrom

College, and with a simple introduction, after the easy manner of

Western Canada, proceeded to hear the story of old Andrew McDermott, the

patriarch of Winnipeg.

"Yes," said Mr. McDermott, "I was among

those of the first year of Lord Selkirk's immigrants. We landed from the

Old Country, at York Factory, on Hudson Bay. The first immigrants

reached the banks of the Red River in the year 1812.

"I am a native of Ireland and embarked

with Owen Keveny—a bright Hibernian—a clever writer, and speaker, who,

poor fellow, was killed by the rival Fur Company, and whose murderer, De

Reinhard, was tried at Quebec. Of course the greater number of Lord

Selkirk's settlers were Scotchmen, but I have always lived with them,

known them, and find that they trust me rather more than they at times

trust each other. I have been their merchant, contractor, treaty-maker,

business manager, counsellor, adviser, and confidential friend."

"But," said the writer, "as having

come to cast in my lot with the people of the Red River, I should be

glad to hear from you about the early times, and especially of the

earlier people of this region, who lived their lives, and came and went,

before the arrival of Lord Selkirk's settlers in 1812." Thus the

story-telling began, and patriarch and questioner made out from

one source and another the whole story of the predecessors of the

Selkirk Colonists.

MOUND BUILDERS' ORNAMENTS, ETC.

A. Ornamental gorget of turtle's plastron.

B. Gorget of sea-shell (1879).

C. Gorget of buffalo bone.

D. Breast or arm ornament of very hard bone.

E. String of beads of birds' leg bones.

Note cross X.

F. One of three polished stones used for gaming.

G. Columella of large sea couch (tropical, used as sinker for

fishing).

"Long before the coming of the

settler, there lived a race who have now entirely disappeared. Not very

far from the Assiniboine River, where Main Street crosses it, is now to

be seen," said the narrator, "Fort Garry—a fine castellated structure

with stone walls and substantial bastions. A little north of this you

may have noticed a round mound, forty feet across. We opened this mound

on one occasion, and found it to contain a number of human skeletons and

articles of various kinds. The remains are those of a people whom we

call 'The Mound Builders,' who ages ago lived here. Their mounds stood

on high places on the river bank and were used for observation. The

enemy approaching could from these mounds easily be seen. They are also

found in good agricultural districts, showing that the race were

agriculturists, and where the fishing is good on the river or lake these

mounds occur. The Mound Builders are the first people of whom we have

traces here about. The Indians say that these Mound Builders are not

their ancestors, but are the 'Very Ancient Men.' It is thought that the

last of them passed away some four hundred years ago, just before the

coming of thewhite

man. At that time a fierce whirlwind of conquest passed over North

America, which was seen in the destruction of the Hurons, who lived in

Ontario and Quebec. Some of their implements found were copper, probably

brought from Lake Superior, but stone axes, hammers, and chisels, were

commonly used by them. A horn spear, with barbs, and a fine shell

sinker, shows that they lived on fish. Strings of beads and fine pearl

ornaments are readily found. But the most notable thing about these

people is that they were far ahead of the Indians, in that they made

pottery, with brightly designed patterns, which showed some taste. Very

likely these Mound Builders were peaceful people, who, driven out of

Mexico many centuries ago, came up the Mississippi, and from its

branches passing into Red River, settled all along its banks. We know

but little of this vanished race. They have left only a few features of

their work behind them. Their name and fame are lost forever.

"And is this all? an earthen pot,

A broken spear, a copper pinEarth's grandest prizes counted in—A

burial mound?—the common lot."

Then the conversation turned upon

the early Frenchmen, who came to the West during the days

of French Canada, before Wolfe took Quebec. "Oh! I have no doubt they

would make a great ado," said the old patriarch, "when they came here.

The French, you know, are so fond of pageants. But beyond a few rumors

among the old Indians far up the Assiniboine River of their remembrance

of the crosses and of the priests, or black robes, as they call them, I

have never heard anything; these early explorers themselves left few

traces. When they retired from the country, after Canada was taken by

Wolfe, the Indians burnt their forts and tried to destroy every vestige

of them. You know the Indian is a cunning diplomatist. He very soon sees

which is the stronger side and takes it. When the King is dead he is

ready to shout, Long live the new King. I have heard that down on the

point, on the south side of the Forks of the two rivers, the Frenchmen

built a fort, but there wasn't a stick or a stone of it left when the

Selkirk Colonists came in 1812. But perhaps you know that part of the

story better than I do," ventured the old patriarch. That is the Story

of the French Explorers.

"Oh! Yes," replied the writer, "you know

the world of men and things about you; I know the world of books and

journals and letters."

"Let us hear of that," said the

patriarch eagerly.

A. Native Copper Drill.

B. Soapstone Conjurer's tube.

C. Flint Skinning Implement.

D. Horn Fish Spear.

E. Native Copper Cutting Knife.

F. Cup found in Rainy River Mound by the Author, 1884.

MOUND BUILDERS' REMAINS

Well, you know the French Explorers were

very venturesome. They went, sometimes to their sorrow, among the

wildest tribes of Indians.

A French Captain, named Verandrye,

who was born in Lower Canada, came up the great lakes to trade for furs

of the beaver, mink, and musk-rat. When he reached the shore of Lake

Superior, west of where Fort William now stands, an old Indian guide,

gave him a birch bark map, which showed all the streams and water

courses from Lake Superior to Lake of the Woods, and on to Lake

Winnipeg. This was when the "well-beloved" Louis XV. was King of France,

and George II. King of England. It was heroic of Verandrye to face the

danger, but he was a soldier who had been twice wounded in battle in

Europe, and had the French love of glory. By carrying his canoes over

the portages, and running the rapids when possible, he came to the head

of Rainy River, went back again with his furs, and after several such

journeys, came down the Winnipeg River from Lake of the Woods, to Lake

Winnipeg, and after a while made a dash across the stormy Lake Winnipeg

and came to the Red River. The places were all unknown, the Indians had

never seen a white man in their country, and the French Captain, with

his officers, his men and a priest, found their way to

the Forks of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers. This was nearly

three-quarters of a century before the first Selkirk Colonists reached

Red River. The French Captain saw only a few Indian teepees at the

Forks, and ascended the Assiniboine. It was a very dry year, and the

water in the Assiniboine was so low that it was with difficulty he

managed to pull over the St. James rapids, and reached where Portage la

Prairie now stands, and sixty miles from the site of Winnipeg claimed

the country for his Royal Master. Here he collected the Indians, made

them his friends, and proceeded to build a great fort, and named it

after Mary of Poland, the unfortunate Queen of France—"Fort de la Reine,"

or Queen's Fort. But he could not forget "The Forks"—the Winnipeg of

to-day—and so gave instructions to one of his lieutenants to stop with a

number of his men at the Forks, cut down trees, and erect a fort for

safety in coming and going up the Assiniboine. The Frenchmen worked

hard, and on the south side of the junction of the Red River with the

Assiniboine, erected Fort Rouge—the Red Fort. This fort, built in 1738,

was the first occupation of the site of the City of Winnipeg. The French

Captain Verandrye, his sons and his men, made further journeys to the

far West, even once coming in sight of the Rocky Mountains. But French

Canada was doomed. In

twenty years more Wolfe was to wrench Canada from France and make it

British. The whole French force of soldiers, free traders, and voyageurs

were needed at Montreal and Quebec. Not a Frenchman seems to have

remained behind, and for a number of years the way to the West was

blocked up. The canoes went to decay, the portages grew up with weeds

and underwood, and the Western search for furs from Montreal was

suspended.

THE INDIANS OF THE RED RIVER.

No man knew the Indian better than

Andrew McDermott. No one knew better how to trade and dicker with the

red man of the prairie. He could tell of all the feuds of tribe with

tribe, and of the wonderful skill of the Fur Companies in keeping order

among the Indian bands. The Red River had not, after the departure of

the French, been visited by travellers for well nigh forty years. No

doubt bands of Indians had threaded the waterways, and carried their

furs in one year to Pigeon River, on Lake Superior, or to Fort

Churchill, or York Factory on Hudson Bay. It was only some ten or

fifteen years before the coming of the Selkirk Colonists that the fur

traders, though they for forty years had been ascending the

Saskatchewan, had visited Red River at all. No missionary had up to the

coming of the Colonists

ever appeared on the banks of the Red River. Some ten years before the

settler's advent, the fur traders on the upper Red River had most bitter

rivalries and for two or three years the fire water—the Indian's

curse—flowed like a flood. The danger appealed to the traders, and from

a policy of mere self-protection they had decided to give out no strong

drink, unless it might be a slight allowance at Christmas and New Year's

time. Red River was now the central meeting place of four of the great

Indian Nations. The Red Pipestone Quarry down in the land of the

Dakotas, and the Roches Percées, on the upper Souris River, in the land

of the wild Assiniboines were sacred shrines. At intervals all the

Indian natives met at these spots, buried for the time being their

weapons, and lived in peace. But Red River, and the country—eastward to

the Lake of the Woods—was really the "marches" where battles and

conflicts continually prevailed. Red River, the Miskouesipi, or Blood

Red River of the Chippewas and Crees, was said to have thus received its

name. Andrew McDermott knew all the Indians as they drew near with

curiosity, to see the settlers and to speculate upon the object of their

coming. The Indian despises the man who uses the hoe, and when the

Colonists sought thus to gain a sustenance from the fertile soil of the field,

they were laughed at by the Indians who caught the French word "Jardiniers,"

or gardeners, and applied it to them.

The Colonists were certainly a puzzle to

the Red man. To the banks of the Red River and to the east of Lake

Winnipeg had come many of the Chippewas. They were known on the Red

River as Sauteurs, or Saulteaux, or Bungays, because they had come to

the West from Sault Ste. Marie, thinking nothing of the hundreds of

miles of travel along the streams. They were sometimes considered to be

the gypsies of the Red men. It was they coming from the lucid streams

emptying into Lake Superior and thence to Lake Winnipeg, who had called

the latter by its name "Win," cloudy or muddy, and "nipiy" water. When

the Colonists arrived, the leading chief of the Chippewas, or Saulteaux,

was Peguis. He became at once the friend of the white man, for he was

always a peaceful, kindly, old Ogemah, or Chieftain.

All the Indians were, at first, kindness

itself to the new comers, and they showed great willingness to supply

food to the hungry settlers, and to assist them in transfer and in

taking possession of their own homes.

The Saulteaux Indians while active

and helpful were really intruders among the Crees, a great Indian

nation, who in language and blood were their relations. As proof of this

the Crees at

this time used horses on the plains. The horse was an importation

brought up the valleys from the Spaniards of Mexico. Seeing his value as

a beast of burden, more fit than the dog which had been formerly used,

they coined the word "Mis-ta-tim," or big dog as the name for the horse.

Their Chiefs were, with their names translated into pronounceable

English, "the Premier," "the Black Robe," "the Black Man," while

seemingly Mache Wheskab—"the Noisy Man"—represented the Assiniboines.

The Crees, so well represented by their doughty Chiefs, are a sturdy

race. They adapt themselves readily enough to new conditions. While the

northern Indian tribes met the Colonists, yet in after days, as had

frequently taken place in days preceding, bands of Sioux or Dakotas,

came on pilgrimages to the Red River. Long ago when the French Captain

Verandrye voyaged to Lake of the Woods, his son and others of his men,

were attacked by Sioux warriors, and the whole party of whites was

massacred in an Island on the Lake. The writer in a later day, near

Winnipeg, met on the highway, a band of Sioux warriors, on horse-back,

with their bodies naked to the waist, and painted with high color, in

token of the fact that they were on the warpath. On occasion it was the

habit of bands of Sioux to find their way to the Red River Valley, and the

people did not feel at all safe, at their hostile attitude, as they bore

the name of the "Tigers of the Plains."

With Saulteaux, Crees, Assiniboines, and

Sioux coming freely among them, the settlers had at first a feeling of

decided insecurity.

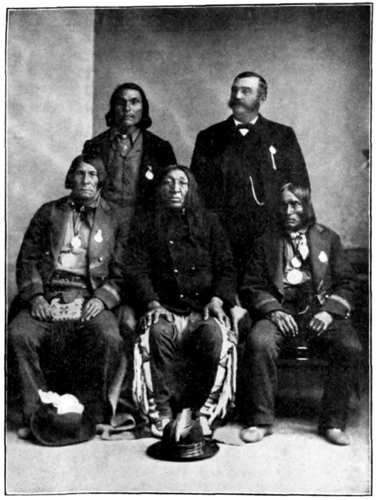

Osoup Agent

Atalacoup Kakawistaha Mistawasis

FOUR CREE CHIEFS OF RUPERT'S LAND

THE MONTREAL MERCHANTS AND MEN.

But the fur trade paid too well to

be left alone by the Montrealers who knew of Verandrye's exploits on the

Ottawa and the Upper Lakes. When Canada became British, many daring

spirits hastened to it from New York and New Jersey States. Montreal

became the home of many young men of Scottish families. Some of their

fathers had fled to the Colonies after the Stuart Prince was defeated at

Culloden, and after the power of the Jacobites was broken. Some of the

young men of enterprising spirit were the sons of officers and men who

had fought in the Seven Years' War against France and now came to claim

their share of the conqueror's spoils. Some men were of Yankee origin,

who with their proverbial ability to see a good chance, came to what has

always been Canada's greatest city, on the Island of Montreal. It was

only half a dozen years after Wolfe's great victory, that a great

Montreal trader, Alexander Henry, penetrated the western lakes to

Mackinaw—the Island of the Turtle, lying between Lakes Huron and Michigan.

At Sault Ste. Marie, "he fell in with a most noted French Canadian,

Trader Cadot, who had married a Saulteur wife. He became a power among

the Indians. With Scottish shrewdness Henry acquired from the Commandant

at Mackinaw the exclusive right to trade on Lake Superior. He became a

partner of Cadot, and they made a voyage as Canadian Argonauts, to bring

back very rich cargoes of fur. They even went up to the Saskatchewan on

Lake Winnipeg. After Henry, came another Scotchman, Thomas Curry, and

made so successful a voyage that he reached the Saskatchewan River, and

came back laden with furs, so that he was now satisfied never to have to

go again to the Indian country. Shortly afterwards James Findlay,

another son of the heather, followed up the fur-traders' route, and

reached Saskatchewan. Thus the Northwest Fur Trade became the almost

exclusive possession of the Scottish Merchants of Montreal. With the

master must go the man. And no man on the rivers of North America ever

equalled, in speed, in good temper, and in skill, the French Canadian

voyageur. Almost all the Montreal merchants, the Forsythes, the

Richardsons, the McTavishes, the Mackenzies, and the McGillivrays, spoke

the French as fluently as they did their own language. Thus they became

magnetic leaders of the French canoemen

of the rivers. The voyageurs clung to them with all the tenacity of a

pointer on the scent. There were Nolins, Falcons, Delormes, Faribaults,

Lalondes, Leroux, Trottiers, and hundreds of others, that followed the

route until they became almost a part of the West and retired in old

age, to take up a spot on some beautiful bay, or promontory, and never

to return to "Bas Canada." Those from Montreal to the north of Lake

Superior were the pork eaters, because they lived on dried pork, those

west of Lake Superior, "Couriers of the Woods," and they fed on

pemmican, the dried flesh of the buffalo. They were mighty in strength,

daring in spirit, tractable in disposition, eagles in swiftness, but

withal had the simplicity of little children. They made short the weary

miles on the rivers by their smoking "tabac"—the time to smoke a pipe

counting a mile—and by their merry songs, the "Fairy Ducks" and "La

Claire Fontaine," "Malbrouck has gone to the war," or "This is the

beautiful French Girl"—ballads that they still retained from the French

of Louis XIV. They were a jolly crew, full of superstitions of the

woods, and leaving behind them records of daring, their names remain

upon the rivers, towns and cities of the Canadian and American

Northwest.

Some thirty years before the arrival

of the Colonists,

the Montreal traders found it useful to form a Company. This was called

the North-West Fur Company of Montreal. Having taken large amounts out

of the fur trade, they became the leaders among the merchants of

Montreal. The Company had an energy and ability that made them about the

beginning of the nineteenth century the most influential force in

Canadian life. At Fort William and Lachine their convivial meetings did

something to make them forget the perils of the rapids and whirlpools of

the rivers, and the bitterness of the piercing winds of the northwestern

stretches. Familiarly they were known as the "Nor'-Westers." Shortly

before the beginning of the century mentioned, a split took place among

the "Nor'-Westers," and as the bales of merchandise of the old Company

had upon them the initials "N.W.," the new Company, as it was called,

marked their packages "XY," these being the following letters of the

alphabet.

Besides these mentioned there were a

number of independent merchants, or free traders. At one time there were

at the junction of the Souris and Assiniboine Rivers, five

establishments, two of them being those of free traders or independents.

Among all these Companies the commander of a Fort was called, "The

Bourgeois" to suit the French tongue of the men.

He was naturally a man of no small importance.

"THE DUSKY RIDERS OF THE PLAINS."

But the conditions, in which both

the traders and the voyageurs lived, brought a disturbing shadow over

the wide plains of the North-West. Now under British rule, the Fur trade

from Montreal became a settled industry. From Curry's time (1766) they

began to erect posts or depots at important points to carry on their

trade. Around these posts the voyageurs built a few cabins and this new

centre of trade afforded a spot for the encampment near by of the Indian

teepees made of tanned skins. The meeting of the savage and the

civilized is ever a contact of peril. Among the traders or officers of

the Fur trade a custom grew up—not sanctioned by the decalogue—but

somewhat like the German Morganatic marriage. It was called "Marriage of

the Country." By this in many cases the trader married the Indian wife;

she bore children to him, and afterwards when he retired from the

country, she was given in real marriage to some other voyageur, or other

employee, or pensioned off. It is worthy of note that many of these

Indian women became most true and affectionate spouses. With the

voyageurs and laborers the conditions were different. They could not

leave the country, they had

become a part of it, and their marriages with the Indian women were bona

fide. Thus it was that during the space from the time of Curry until the

arrival of the Selkirk Colonists upwards of forty years had elapsed, and

around the wide spread posts of the Fur Trading Companies, especially

around those of the prairie, there had grown up families, which were

half French and half Indian, or half English and half Indian. When it

could be afforded these children were sent for a time to Montreal, to be

educated, and came back to their native wilds. On the plain between the

Assiniboine and the Saskatchewan, a half-breed community had sprung up.

From their dusky faces they took the name "Bois-Brulés," or "Charcoal

Faces," or referring to their mixed blood, of "Metis," or as exhibiting

their importance, they sought to be called "The New Nation." The blend

of French and Indian was in many respects a natural one. Both are

stalwart, active, muscular; both are excitable, imaginative, ambitious;

both are easily amused and devout. The "Bois-Brulés" growing up among

the Indians on the plains naturally possessed many of the features of

the Indian life. The pursuit of their fur-bearing animals was the only

industry of the country. The Bois-Brulés from childhood were familiar

with the Indian pony, knew all his tricks and habits, began to ride with

all the

skill of a desert ranger, were familiar with fire-arms, took part in the

chase of the buffalo on the plains, and were already trained to make the

attack as cavalry on buffalo herds, after the Indian fashion, in the

famous half-circle, where they were to be so successful in their later

troubles, of which we shall speak. Such men as the Grants, Findlays,

Lapointes, Bellegardes, and Falcons were equally skilled in managing the

swift canoe, or scouring the plains on the Indian ponies. We shall see

the part which this new element were to play in the social life and even

in the public concerns of the prairies.

THE STATELY HUDSON'S BAY COMPANY.

The last of the elements to come

into the valley of the Red River and to precede the Colonists, was the

Hudson's Bay Company—even then, dating back its history almost a century

and a half. They were a dignified and wealthy Company, reaching back to

the times of easy-going Charles II., who gave them their charter. For a

hundred years they lived in self-confidence and prudence in their forts

of Churchill and York, on the shore of Hudson Bay. They were even at

times so inhospitable as to deal with the Indians through an open window

of the fort. This was in striking contrast to the "Nor'-Wester"

who trusted the Indians and lived among them with the freest

intercourse. For the one hundred years spoken of, the Indians from the

Red River Country, the Saskatchewan, the Red River and Lake Winnipeg,

found their way by the water courses to the shores of the Hudson Bay.

But the enterprise of the Montreal merchants in leaving their forts and

trading in the open with the Indians, prevented the great fleets of

canoes, from going down with their furs, as they had once done to

Churchill and York. The English Company felt the necessity of starting

into the interior, and so within six years of the time of the expedition

of Thomas Curry, appeared five hundred miles inland from the Bay, and

erected a fort—Fort Cumberland—a few hundred yards from the "Nor'-Westers'"

Trading House, on the Saskatchewan River. By degrees before the end of

the century almost every place of any importance, in the fur-producing

country, saw the two rival forts built within a mile or two of each

other. Shortly before the end of the 18th Century, the "Nor'-Westers"

came into the Red River Valley and built one or two forts near the 49th

parallel, N. lat.—the U.S. boundary of to-day. But four years after the

new Century began, the "Nor'-Westers" decided to occupy the "Forks" of

the Red and Assiniboine River, near where Verandrye's Fort Rouge had been

built some sixty years before. Evidently both companies felt the

conflict to be on, in their efforts to cover all important parts, for

they called this Trading House Fort Gibraltar, whose name has a decided

ring of the war-like about it. It is not clear exactly where the

Hudson's Bay post was built, but it is said to have rather faced the

Assiniboine than the Red River, perhaps near where Notre Dame Avenue

East, or the Hudson's Bay stores is to-day. It was probably built a few

years after Fort Gibraltar, and was called "Fidler's Fort." By this

time, however, the Hudson's Bay Company, working from their first post

of Cumberland House, pushed on to the Rocky Mountains to engage in the

Titanic struggle which they saw lay ahead of them. One of their most

active agents, in occupying the Red River Valley, was the Englishman

Peter Fidler, who was the surveyor of this district, the master of

several forts, and a man who ended his eventful career by a will

made—providing that all of his funds should be kept at interest until

1962, when they should be divided, as his last chimerical plan should

direct. It thus came about that when the Colonists arrived there were

two Traders' Houses, on the site of the City of Winnipeg of to-day,

within a mile of one another, one representing a New World, and the

other an Old World type of mercantile life. It was plain that

on the Plains of Rupert's Land there would come a struggle for the

possession of power, if not for very existence. |