|

Pioneering to-day is not so serious

a matter as it once was. To the frontiers' man now it involves little

risk, and little thought, to dispose of his holding, and make a dash

further West for two or three hundreds of miles across the plains. When

he wishes more land for his growing sons, he "sells out," fits up his

commodious covered wagon, called "the prairie schooner," and with

implements, supplies, cattle and horses, starts on the Western "trail."

His wife and children are in high spirits. When a running stream or

spring is reached on the way he stops and camps. His journey taken when

the weather is fine and when the mosquitoes are gone is a diversion. The

writer has seen a family which went through this gypsy-like "moving" no

less than four times. At length the settler finds his location, has it

registered in the nearest Land Office and calls it his. With ready axes,

the farmer and his sons cut down the logs which are to make their

dwelling. The children explore the new farm lying covered

with its velvet sod, as it has done for centuries; they gather its

flowers, pluck its wild fruits, chase its wild ducks or grouse or

gophers. Health and homely fare make life enjoyable. Subject to the

incidents and interruptions of every day, which follow humanity, it

seems to them a continual picnic.

But how different was the fate of

the worn-out Selkirk Colonists. The memory of a wretched sea voyage, of

a long and dreary winter at Nelson Encampment, and of a fifty-five days'

journey of constant hardship along the fur traders' route were impressed

upon their minds. The thought of fierce rivers and the dangers of

portage and cascade still haunted them, and now everything on the banks

of Red River was strange. On their arrival the flowers were blooming,

but they were prairie flowers, and unknown to them. The small Colony

houses which they were to occupy would be uncomfortable. The very sun in

the sky seemed alien to them, for the Highland drizzle was seen no more.

The days were bright, the weather warm, the nights cool, and there was

an occasional August thunderstorm, or hailstorm which alarmed them. The

traders, the Indians, the half-breed trappers, and runners were all new

to them. Their Gaelic language, which they claimed as that of Eden, was

of little value to them except where an occasional company-servant

chanced to be a countryman of their own. They were without money, they

were dependent upon Lord Selkirk's agents for shelter and rations. The

land which they hoped to possess was there awaiting them, but they had

no means for purchasing implements, nor were the farming requisites to

be found in the country. Horses there were, but there were only two or

three individual cattle within five hundred miles of them.

If they had sung on their sorrowful

leaving, "Lochaber no more," the words were now turned by their

depressed Highland natures into a wail, and they sang in the words of

their old Psalms of "Rouse's" version:

By Babel's streams we sat and

wept,

When Zion we thought on.

They thought of their crofts and clachans,

where if the land was stingy, the gift of the sea was at hand to supply

abundant food.

But this was no time for sighs or regrets.

The Hudson's Bay traders from

Brandon House were waiting for expected goods, and Messrs. Hillier and

Heney, who were the Hudson's Bay Company officers for the East Winnipeg

District, had arduous duties ahead of them. But though the orders to

prepare for the Colonists had been sent on in good time, there

was not a single bag of pemmican or any other article of provision

awaiting the hapless settlers. The few French people who were freemen,

lived in what is now the St. Boniface side of the river, were only

living from hand to mouth, and the Company's people were little better

provided. The river was the only resource, and from the scarceness of

hooks the supply of fish obtainable was rather scanty.

As the Colonists and their leader were

strangers they desired leisure to select a suitable location for their

buildings. For the time being their camp was at the Forks, on the east

side of the river, a little north of the mouth of the Assiniboine.

The Governor, Miles Macdonell, on

the 4th of September, summoned three of the North-West Company

gentlemen, the free Canadians beside whom they were encamped, and a

number of the Indians to a spectacle similar to that enacted by St.

Lawson, at Sault Ste. Marie, nearly a hundred and fifty years before.

The Nor'-Westers had not permitted their employees to cross the river.

Facing, as he did, Fort Gibraltar, across the river, the Governor

directed the patent of Lord Selkirk to his vast concession to be read,

"delivering and seizin were formally taken," and Mr. Heney translated

some part of the Patent into French for the

information of the French Canadians. There was an officers' guard under

arms; colors were flying and after the reading of the Patent all the

artillery belonging to Lord Selkirk, as well as that of the Hudson's Bay

Company, under Mr. Hillier, consisting of six swivel guns, were

discharged in a grand salute.

At the close of the ceremony the gentlemen

were invited to the Governor's tent, and a keg of spirits was turned out

for the people.

Having made such disposition as we shall

see of the people, Governor Macdonell went with a boat's crew down the

river to make a choice of a place of settlement for the Colonists. A

bull and cow and winter wheat had been brought with the party, and these

were taken to a spot selected after a three days' thorough investigation

of both banks of the river for some miles below the Forks. The place

found most eligible was "an extensive point of land through which fire

had run and destroyed the wood, there being only burnt wood and weeds

left." This was afterwards called Point Douglas.

He had, as we shall see, dispatched

the settlers to their wintering place up the Red River on the 6th of

September, and set some half-dozen men, who were to stay at the Forks,

to work clearing the ground for sowing winter wheat.

An officer was left with the men to trade with Indians for fish and meat

for the support of the workers.

The winter, which is sharp, crisp and

decided in all of Rupert's Land, was approaching, so that their

situation began to be desperate.

Governor Macdonell's chief care was for

the safety and comfort during the winter of his helpless Colonists.

Sixty miles up the Red River from the

Forks was a settlement of native people—chiefly French half-breeds—and

to this place called Pembina came in the buffaloes, or if not they were

easily reached from this settlement. But the poor Scottish settlers had

no means of transport, and the way seemed long and desolate to them to

venture upon, unaccompanied and unhelped. Governor Macdonell did his

best for them, and succeeded in inducing the Saulteaux Indians, who

seemed friendly, to guide and protect them as they sought Pembina for

winter quarters.

The Indians had a few ponies and

mounted on these they undertook to conduct the settlers to their

destination. The caravan was grotesquely comical as it departed

southward. The Indians upon their "Shaganappi ponies," as they are

called, like mounted guards protecting the men, women and children of

the Colony who trudged wearily on foot. The Indians were kind to

their charge, but the Redman loves a joke, and often indulges in

"horse-play." The demure Highlander looked unmoved upon the Indian

pranks. The Indians also hold everything they possess on a loose tenure.

The Highlander who was forced to surrender the gun, which his father had

carried at the battle of Culloden, failed to see the humour of the

affair, and the Highland woman who was compelled to give up her gold

marriage ring, because some prairie brave wanted it, was unable to see

the ethics of the Saulteaux guide who robbed her. The women became very

weary of their journey, but their mounted guardians only laughed,

because they were in the habit on their long marches of treating their

own squaws in the same manner.

To Pembina at length they came—worn

out, dusty and despondent. Here they erected tents or built huts. The

settlers reached Pembina on the 11th of September, and Macdonell and an

escort of three men, all on horseback, arrived on the 12th. Arrived at

Pembina Macdonell examined the ground carefully, and selected the point

on the south side of the Pembina River at its juncture with the Red

River as a site for a fort. His men immediately camped here. Great

quantities of buffalo meat were brought in by the French Canadians and

Indians. Some of this was sent down to the Forks to the party which had

remained to built a hut at that point for

stores. At Pembina a storehouse was built immediately, and having given

directions to erect several other buildings, the Governor returned by

boat to the Forks. On the 27th of October Owen Keveny, in charge of the

second detachment of Colonists, arrived with his party, largely of

Irishmen. These men were taken on to Pembina. After great activity the

buildings were ready by the 21st of November to house the whole of the

two parties now united in one band of Colonists. The Governor and

officers' quarters were finished on December 27th. Macdonell reports to

Lord Selkirk that "as soon as the place at Pembina took some form and a

decent flagstaff was erected on it, it was called Fort Daer." It is said

that in most years the buffaloes were very numerous and so tame that

they came to the Trader's Fort and rubbed their backs upon its stockaded

enclosure. There was this year plenty of buffalo meat and the Scotch

women soon learned to cook it into "Rubaboo," or "Rowschow," after the

manner of the French half-breeds. Toward spring food was scarcer.

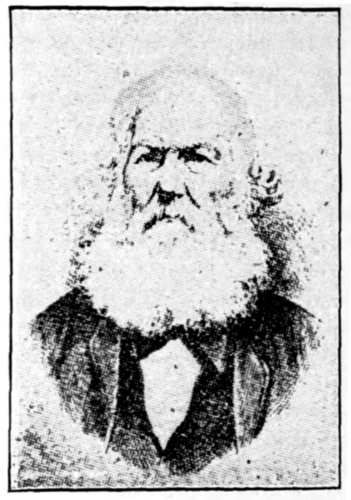

HON. DONALD GUNN

Schoolmaster, Naturalist and Legislator.

York Factory, 1813; Red River, 1823; Died at Little Britain, 1878.

In May the winterers of Pembina

returned to their settlement at the Colony. They sought to begin the

cultivation of their farms, but they were helpless. The tough prairie

sod had to be broken up and worked over, but the only implement which

the Colonist had to use was a simple

hoe, the one harrow being incomplete. The crofters were poor farmers,

for they were rather fishermen. But the fish in Red River were scarce in

this year, so that even the fisher's art which they knew was of little

avail to them. The summer of 1813 was thus what the old settlers would

call an "Off-Year," for even the small fruits on the plains were

far from abundant. These being scarce, the chief food of the settlers

for all that summer through was the "Prairie turnip." This is a variety

of the pea family, known as the Astragalus esculenta, which with its

large taproot grows quite abundantly on the dry plains. An old-time

trader, who was lost for forty days and only able to get the Prairie

turnip, practically subsisted in this way. Along with this the settlers

gathered quantities of a very succulent weed known as "fat-hen," and so

were kept alive. The Colonists knowing now what the soil could produce

obtained small quantities of grain and even with their defective means

of cultivation, in the next year demonstrated the fertility of the soil

of the country.

It was somewhat distressing to the

Colonists again in 1813 to make the journey of sixty miles to Pembina,

trudging along the prairie trail, but there was no other resource. The

treatment of the Colonists by the "Nor'-Westers" had not thus far been

unfriendly and the Canadian traders had even imported a few cattle,

pigs, and poultry for the use of the settlers, and for these favors

Governor Macdonell expressed his hearty thanks to the Montreal Company.

The fatigues and mishaps of the journey to Pembina were, however, only

the beginning of trouble for the winter. The reception by the French

half-breed residents of Pembina was not

now so friendly as that of the previous winter. At first the Nor'-Wester

feeling had been one of contempt for the Colonists and pity for them in

their hunger and miseries. The building of Fort Daer was an evidence of

occupation that caused the jealous Canadian pioneers to pause. The

reception of the second season was thus decidedly cool. The struggling

settlers found before the winter was over that troubles come in troops.

Very heavy snows fell in the winter of 1813-14. This brought two

difficulties. It prevented the buffaloes coming freely from the open

plains into the rivers and sheltered spots. The buffalo being a heavy

animal is helpless in the snow. The other difficulty was that the

settlers could not go on the chase with freedom. Unfortunately the

Colonists were not able to use the snowshoe as could the lively Metis.

The settlers well nigh perished in seeking the camp whither the native

hunters had gone to follow the buffalo. Indeed the Colonists had the

conviction that a plot to murder two of their most active leaders was

laid by the French half-breeds whose sympathies were all with the "Nor'-Westers."

The climax of feeling was reached

when Governor Macdonell, who was with the Colonists at Pembina, issued a

most unwise proclamation, which to the Nor'-Westers seemed an illegality

if not an impertinence. Dependent as the settlers

were on the older Company for supplies and assistance this was nothing

less than an act of madness.

By proclamation, on the 8th of January,

1814, Macdonell forbade any traders of "The Honorable Hudson's Bay

Company, the North-West Company, or any individual or unconnected trader

whatever to take out any provisions, either of flesh, grain or

vegetables, from the country.

The embargo was complete.

In Governor Macdonell's defence it should

be said that he offered to pay by British bills for all the provisions

taken, at customary rates.

This assertion of sovereignty set on fire

the Nor'-Westers and their sympathizers.

Not only was this extreme step taken, but

John Spencer, a subordinate of Macdonell was sent west to Brandon House,

found an entrance into the North-West Fort at the mouth of the Souris

River and seizing some twenty-five tons of dry buffalo meat took it into

his own fort.

It is quite true that Governor Macdonell

expected new bands of Colonists and thus justified himself in his

seizure. It is to the credit of the Nor'-Westers that they restrained

themselves and avoided a general conflict, but evidently they only bided

their time.

No breach of the peace occurred

however, before

the return of the Colonists from Pembina to the Colony Houses. The

settlers occupied their homes in the best of spirits, and began to sow

their wheat, but they were still greatly checked by the absence of the

commonest implements of farm culture. Had Lord Selkirk known the true

state of things on Red River, he would never have continued to send new

bands of Colonists so imperfectly fitted for dealing with the

cultivation of the soil.

The founder's mind had been fired, both by

the opposition of Sir Alexander Mackenzie and by the successful arrival

of his two bands of Colonists at the Red River, to make greater efforts

than ever.

This he did by sending out a third

party in all nearly a hundred strong, under the leadership of a very

capable man—Archibald Macdonald. This band of settlers in 1813 were

bound on the ship Prince of Wales for York Factory. A very serious

attack of ship fever filled the whole ship's crew with alarm. Several

well-known Colonists died. The Captain, alarmed, refused to go on to his

destination, but ran the ship into Fort Churchill and there disembarked

them. Further deaths took place at this point. In the spring there was

no resource but to trudge over the rocky ledges and forbidding

desolation of more than a hundred miles between the Fort Churchill and York

Factory. Only the stronger men and women were selected for the journey.

On the 6th of April, 1814, a party of twenty-one males and twenty

females started on this now celebrated tramp. At first the party began

to march in single file, but finding this inconvenient changed to six

abreast. Unaccustomed to snowshoes and sleds the Colonists found the

snowy walk very distressing. Three fell by the way and were carried on

by the stronger men. The weather was very cold. A supply of partridges

was given them on starting, and the party was met by hunters sent from

York Factory to meet them, who brought two hundred partridges, killed by

the way. York Factory was reached on the 13th of April. This band of

Colonists were superior to any who had come in the former parties. Many

of them, as we shall see, did not remain in the Colony. A list of this

party may be found in the Appendix. After remaining a month at York

Factory, on the 27th of May, this heroic band went on their way to Red

River, and reached their destination in time to plant potatoes for

themselves and others. Comrades left behind at Churchill found their way

to Red River. Lots along Red River were now being taken up by the

settlers, and here they sought to found homes under a northern sky. Old

and new settlers were now hopeful, but their hopes of peace and

happiness were soon to be dashed to pieces.

The arrival of the third year's Colonists

provoked still greater opposition. Feeling had been gradually rising

against the new settlers at every new arrival. The excellence of the

later immigrants but led their opponents to be irritated. |