|

Stone forts and ermined judges were not,

to the mind of the unbridled and ungovernable Metis. True, the French

mind has a love for show and circumstance and dignity of demeanor, but

the conviction had taken hold of the people of Red River, and especially

of the French half-breeds, that these meant curtailment of their

freedom. They felt the dice were loaded against them.

But, now, in the year after Sinclair

and his friends had shown such a firm front to Governor Christie, and

when something like a feudal system was being introduced into the Red

River Settlement, a new surprise came upon French and English alike.

This was immediately after the terrible visitation of a plague, which

had cut down one-sixteenth of the whole population. It was the arrival

of a party of the Sixth Royal Regiment of Foot, along with artillery and

engineers, amounting in all to five hundred souls. The breath of the

people was taken away by this demonstration of force, and a chronicler of

the time says: "From the moment they arrived the high tone of lawless

defiance and internal disaffection raised by our people against the laws

and the authorities of the place were reduced to silence." Colonel

Crofton, in command of the troops, was appointed Governor of the

Settlement, and he proved a wise and honorable administrator. The

regiment gained golden opinions from the people, and as they spent

during their short stay of two years, a sum of £15,000 in supplies, it

was, indeed, a golden age for the hard-working Colonists. The leaving of

the regiment was regretted by the Colony.

Having now entered on a career of

government by force, it would not do to let it drop. Hence the

authorities enlisted in Britain a number of old pensioners, and under

command of Major Caldwell, who was also to act as Governor of the

Settlement, sent out, in each of two successive years, some seventy of

these discharged soldiers to act as guardians of the peace. It was

pretty well agreed that these men, to whom were given holdings of small

pieces of land to the west of Fort Garry, now in the St. James District

of Winnipeg, were simply imitators in conduct and disposition of the De

Meurons, who had so vexed the Colonists. Major Caldwell, too, by his

lack of business habits and his selfishness, alienated all the leading

men of the Colony, so that they refused to sit with him in Council. It

was the common opinion that the turbulence and violence of the

pensioners was so great that, as one of the Company said, "We have more

trouble with the pensioners than with all the rest of the Settlement put

together." The pensioners were certainly absolutely useless for the

purpose for which they had been sent, that is to preserve order in the

country. The Metis, at any rate, spoke of them with derision.

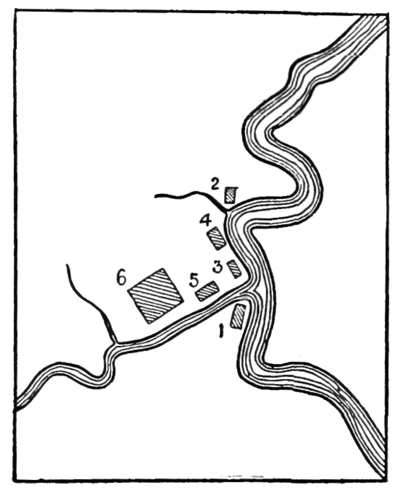

PLAN OF FORT GARRY and of the other forts of Winnipeg.

1, Fort Rouge; 2, Fort Douglas; 3, Fort Gibraltar; 4, Fidler's Fort;

5, First Fort Garry; 6, Fort Garry.

In the year following the removal of

the troops the policy of preventing the French half-breeds

from buying and selling furs with the Indians was being carried out by

Judge Thom, the relentless ogre of the law. Four men of the Metis had

been arrested; of these the leader was William Sayer. He was the

half-breed son of an old French bourgeois of the Northwest Company. He

had been liberated on bail, and was to come up for trial in May. The

charge against him was of buying goods with which to go on a trading

expedition to Lake Manitoba.

Possibly the case would be easily disposed

of, and most likely dismissed with a trifling fine, although it was true

that Sayer had made a stiff resistance on his being arrested. This

violent resistance was but an example of the bitter and dangerous spirit

that was developing among the Metis.

A brave and restless man was now

growing to have a dominating influence over the French half-breeds. This

was Louis Riel, a fierce and noisy revolutionist, ready for any

extremity. He was a French half-breed, was owner of a small flour mill

on the Seine River, and he was the father of the rebel chief of later

years. The day fixed for the Sayer trial by the legal authorities was a

most unfortunate one. It was on May 17th, which on that year was

Ascension Day, a day of obligation among the Catholic people of the

Settlement. It was noticeable that

there was much ferment in the French parishes. Louis Riel, who was a

violent, but effective speaker, of French, Irish and Indian descent,

busied himself in stirring up resistance. The fact that it was a Church

day for the Metis made it easy for them to gather together. This they

did by hundreds in front of the St. Boniface Cathedral, where, piling up

their guns, with which all the men were armed, at the Church door, they

then entered and performed their sacred duties. At the close of the

service, Riel, "the miller of the Seine," made a fiery oration,

advocating the rescue of their compatriot Sayer, who was to be held for

trial at the Court House. A French sympathizer said of this public

meeting: "Louis Riel obtained a veritable triumph on that occasion, and

long and loud the hurrahs were repeated by the echoes of the Red River."

And now, under Riel's direction, by

a concerted action, movement of the whole body was made to cross the Red

River and march to the Court House, which stood beside the wall of Fort

Garry. To allow the five hundred men to cross easily, Point Douglas was

selected, and here by ferry boats, said to have been provided by James

Sinclair, the English half-breed leader of whom we have spoken, the

party crossed, and worked up to the highest pitch of excitement, stalked

up the mile or two to the Court House.

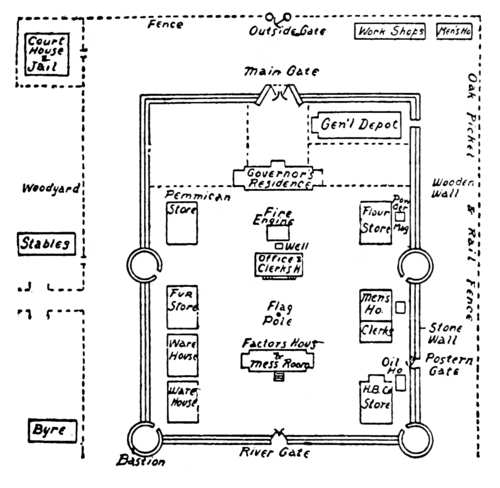

PLAN OF FORT GARRY

South portion with stone wall and bastions built in 1835.

North portion with wooden wall and stone north gate still standing,

built in 1850.

Though somewhat anxious, the

Governor and Court officials passed through the excited crowd which

surrounded the Court House. It was expected that the Governor would

order out a guard of pensioners to protect the Court, but he had

dispensed with this, and so he, Recorder Thom,

and the Magistrate, took their seats upon the elevated platform of

Justice precisely at eleven o'clock. Sayer's case was called first, but

he was held by the Metis outside of the Court room. Other unimportant

business was then taken up until one o'clock. An Irish relative of old

Andrew McDermott, named McLaughlin, attempted to interfere, but was

instantly suppressed. The Court then sent a suggestion to the Metis that

they should appoint a leader with a deputation to enter the Court room

with Sayer and state their case. This proposal was accepted, and James

Sinclair, the English half-breed leader, undertook the duty. Sayer was

then brought in, guarded by twenty of his compatriots, fully armed,

while fifty Metis guards stood at the gates of the Court House

enclosure. An attempt was then made to select a jury, but it was

fruitless. Sayer next confessed that he had traded for furs with an

Indian. The Court then gave a verdict of guilty, whereupon Sayer proved

that a Hudson's Bay officer named Harriott, had given him authority to

trade. The other three cases against the Metis were not proceeded with,

and Governor, Recorder, officials and spectators all left the Court

room, the mob being of the impression that the prisoners had been

acquitted, and that trading for furs was no longer illegal. Though this

was not the decision yet the crowd so took it up, and made the

welkin ring with shouts (Le Commerce est libre, vive la liberté)

"Commerce is free, long live liberty."

The Metis then crossed the river to St.

Boniface, and after much cheering, fired several salutes with their

guns. It was their victory, but it was one in which the vast mass of the

English-speaking rejoiced for the bands of tyranny were broken. Judge

Thom, under instructions from Governor Simpson, never acted as Recorder

again, but was simply Secretary of the Court, and another reigned in his

stead. After this the Court was largely without authority, and as has

been said the rescue of prisoners was not an infrequent occurrence in

the future life of the Settlement. |