|

Alexander Ross was a Scottish Highlander,

who came to Glengarry in Canada, quite a century ago, joined Astor's

expedition, went around Cape Horn and in British Columbia rose to be an

officer in the Northwest Company. He married the daughter of an Indian

Chief at Okanagan, came over the Rocky Mountains, and was given by Sir

George Simpson a free gift of a farm, where Ross and James Streets are

now found in Winnipeg. This land is to-day worth many millions of

dollars. Ross was also fond of hunting the buffalo, and we are fortunate

in having his spirited story of 1840.

In the leafy month of June carts

were seen to emerge from every nook and corner of the Settlement bound

for the plains. As they passed us, many things were discovered to be

still wanting, to supply which a halt had to be made at Fort Garry shop;

one wanted this thing, another that, but all on credit. The day of

payment was yet to come; but payment was promised. Many on the present

occasion were supplied,

many were not; they got and grumbled, and grumbled and got, till they

could get no more; and at last went off, still grumbling and

discontented.

From Fort Garry the cavalcade and

camp-followers were crowding on the public road, and thence, stretching

from point to point, till the third day in the evening, when they

reached Pembina, the great rendezvous of such occasions. When the

hunters leave the Settlement it enjoys that relief which a person feels

on recovering from a long and painful sickness. Here, on a level plain,

the whole patriarchal camp squatted down like pilgrims on a journey to

the Holy Land, in ancient days: only not so devout, for neither scrip

nor staff were consecrated for the occasion. Here the roll was called,

and general muster taken, when they numbered on the occasion 1,630

souls: and here the rules and regulations for the journey were finally

settled. The officials for the trip were named and installed into their

office, and all without the aid of writing materials.

The camp occupied as much ground as

a modern city, and was formed in a circle: all the carts were placed

side by side, the trams outward. Within this line, the tents were placed

in double, treble rows, at one end; the animals at the other in front of

the tents. This is the order in all dangerous places: but when no

danger is feared, the animals are kept on the outside. Thus, the carts

formed a strong barrier, not only for securing the people and the beasts

of burden within, but as a place of shelter and defence against an

attack of the enemy without.

There is, however, another appendage

belonging to the expedition, and to every expedition of the kind; and

you may be assured they are not the least noisy. We allude to the dogs

or camp followers. On the present occasion they numbered no fewer than

542; sufficient of themselves to consume no small number of animals a

day, for, like their masters, they dearly relish a bit of buffalo meat.

These animals are kept in summer as they

are, about the establishments of the fur traders, for their services in

the winter. In deep snows, when horses cannot conveniently be used, dogs

are very serviceable to the hunters in these parts. The half-breed,

dressed in his wolf costume, tackles two or three sturdy curs into a

flat sled, throws himself on it at full length, and gets among the

buffalo unperceived. Here the bow and arrow play their part to prevent

noise; and here the skillful hunter kills as many as he pleases, and

returns to camp without disturbing the band.

But now to our camp again—the

largest of its kind perhaps in the world. A council was held for

the nomination of chiefs or officers for conducting the expedition. Two

captains were named, the senior on this occasion being Jean Baptiste

Wilkie, an English half-breed brought up among the French, a man of good

sound sense and long experience, and withal a bold-looking and discreet

fellow, a second Nimrod in his way. Besides being captain, in common

with others, he was styled the great war chief or head of the camp, and

on all public occasions he occupied the place of president.

The hoisting of the flag every

morning is the signal for raising camp. Half an hour is the full time

allowed to prepare for the march, but if anyone is sick, or their

animals have strayed, notice is sent to the guide, who halts until all

is made right. From the time the flag is hoisted however, till the hour

of camping arrives, it is never taken down. The flag taken down is a

signal for encamping, while it is up the guide is chief of the

expedition, captains are subject to him, and the soldiers of the day are

his messengers, he commands all. The moment the flag is lowered his

functions cease and the captains and soldiers' duties commence. They

point out the order of the camp, and every cart as it arrives moves to

its appointed place. This business usually occupies about the same time

as raising camp in the morning, for everything moves with the regularity

of clockwork.

The captains and other chiefs have agreed

on rules to govern the expedition, such as, that no buffaloes are to be

run on Sunday, no party is to lag behind or to go before, no one may run

a buffalo without a general order, etc. The punishment for breaking the

laws are for a first offence: the offender had his saddle and bridle cut

up: for the second, to have the coat taken off his back and cut up: for

the third, the offender was flogged. Any theft was punished by the

offender being three times proclaimed "THIEF," in the middle of the

camp.

On the 21st of June, after the priest had

performed mass, for many were Roman Catholics, the flag was unfurled at

about six or seven o'clock and the picturesque line was formed over the

prairie, extending some five or six miles towards the southwest. It was

the ninth was gained. This was a journey of about 150 day from Pembina

before the Cheyenne River miles, and on the nineteenth day, at a

distance of 250 miles, the destined hunting grounds were reached. On the

4th of July, since the encampment was in the United States, the

compliment was paid of having the first buffalo race.

No less than 400 huntsmen, all mounted and

anxiously waiting for the word "Start," took up their position in a line

at one end of the camp, while Captain Wilkie issued his orders.

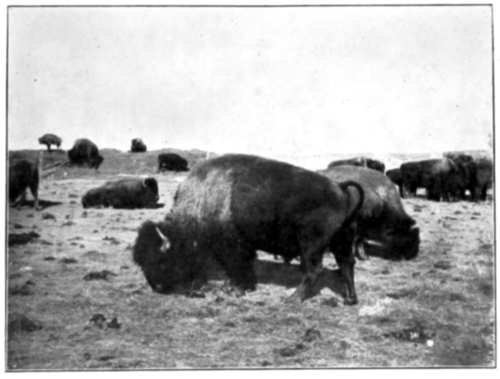

HERD OF BUFFALOES FEEDING ON THE HIGH PLAINS

At eight o'clock the whole cavalcade broke

ground, and made for the buffaloes. When the horsemen started the

buffaloes were about a mile and a half distant, but when they approached

to about four or five hundred yards, the bulls curled their tails or

pawed the ground. In a moment more the herd took flight, and horse and

rider are presently seen bursting upon them, shots are heard, and all is

smoke, dust and hurry, and in less time than we have occupied with a

description a thousand carcasses strew the plain.

When the rush was made, the earth seemed

to tremble as the horses started, but when the animals fled, it was like

the shock of an earthquake. The air was darkened, the rapid firing, at

first, soon became more and more faint, and at last died away in the

distance.

In such a run, a good horse and

experienced rider will select and kill from ten to twelve buffaloes at

one heat, but in the case before us, the surface was rocky and full of

badger holes. Twenty-three horses and riders were at one moment all

sprawling on the ground, one horse gored by a bull, was killed on the

spot, two more were disabled by the fall. One rider broke his shoulder

blade, another burst his gun, and lost three fingers by the accident,

another was struck on the knee by an exhausted bull. In the evening no

less than 1,375 tongues were brought into camp.

When the run is over the hunter's work is now retrograde. The last

animal killed is the first skinned, and night not unfrequently,

surprises the runner at his work. What then remains is lost and falls to

the wolves. Hundreds of dead buffaloes are often abandoned, for even a

thunderstorm, in one hour, will render the meat useless.

The day of a race is as fatiguing on the

hunter as on the horse, but the meat well in the camp, he enjoys the

very luxury of idleness.

Then the task of the women begins, who do

all the rest, and what with skins, and meat and fat, their duty is a

most laborious one.

It is to be regretted that much of the

meat is wasted. Our expedition killed not less than 2,500 buffaloes, and

out of all these made 375 bags of pemmican, and 240 bales of dried meat;

750 animals should have made that amount, so that a great quantity was

wasted. Of course, the buffalo skins were saved and had their value.

Our party were now on the Missouri and

encamped there. A few traders went to the nearest American fort, and

bartered furs for articles they needed.

After passing a week on the banks of

the Missouri we turned to the West, when we had a few races with various

success. We were afterwards led backwards and forwards at the pleasure

of the buffalo herds. They crossed and recrossed our

path until we had travelled to almost every point of the compass.

Having had various altercations with the

Indians, the party reached Red River, bringing about 900 lbs. of buffalo

meat in each cart, making more than one million pounds in all. The

Hudson's Bay Company took a considerable amount of this, and the

remainder went to supply the wants of the Red River Settlement for

another year. |