|

"When the forts which la Verendrye and his sons had built were abandoned

by la Corne, the Indian trade passed north to the posts of the Hudson's

Bay Company once more. The transfer of this trade foreshadowed a more

important change. French sovereignty in the northern part of the

American continent was nearing its end; and a few years after the fur

trade of the west passed from the Canadian companies to the hands of

their English rival, Canada itself was ceded to Britain by France. "When

the cession was finally completed by the treaty of Paris in 1763,

British merchants were not slow to avail themselves of the business

opportunities which were offered by the newly acquired colony, and many

of them settled in Montreal. Such men were not likely to neglect the fur

trade, which had proved so profitable to the Canadian merchants in spite

of the rapacity of government officials; and the Hudson's Bay Company

soon found its monopoly challenged by competitors keener, more

energetic, and more persistent than the French companies had ever been.

Its factors might despise these independent traders and denounce them as

"peddlers'';, but in a few years they were sapping its business in every

part of its great territory.

Michilimackinac was the first objective point of these adventurous

traders. Alexander Henry, a youth who had hardly reached his majority,

had gone with General Amherst's army to the siege of Quebec in 1759; but

before the end of 1761 he was in Michilimackinac with a cargo of goods

to be bartered for furs. Young Henry was only one of the many who had

reached the outlet of Lake Superior on the same quest. Beyond them lay

the great west, and it cast its spell upon these energetic Britishers,

just as it had done upon the French for more than a hundred years. The

wealth which the French had found in the vast interior might be theirs

also, the trails of the French were open to them; and so in a few years

they had penetrated to the most remote points ever reached by their

predecessors.

The

early trading expeditions which started out from Michilimackinac did not

reach the prairies. The Indians in the neighborhood of Rainy Lake had

greatly appreciated the trading posts established there by the French,

and greatly missed the articles sold at these posts, when the French

abandoned them. So eager were they to secure a new supply that the first

English traders, who reached Rainy Lake in 1765, were plundered by the

natives and could not proceed further. Another attempt to reach the far

west was made in the next year; but again the Rainy River Indians took

all the goods, and the trader went back empty-handed. A third attempt,

probably made by Thomas Curry, was more successful, for the Indians took

only a part of the goods, and the trader was allowed to carry the

remainder to a point on die Saskatchewan Curry spent some time traveling

near Fort Bourbon and was so successful that he had no need to go

further west. He returned to Canada with such a rich cargo of furs that

he could retire from business with a comfortable fortune

James Finlav, a merchant of Montreal, spent the winter of In 1770-1 at

Fort Bourbon, but in the spring he ascended the river to its tor*s and

passed the following winter at Fort Nipawi. He, too, was very successful

and in a few years went back to Montreal a wealthy man. He was the

father of the James who became prominent in the North-West Company in

the early part of the nineteenth

century and whose name had been given to one of our- western rivers.

Of

all the early British traders in the west none were more shrewd or

enterprising than the three Frobislier brothers. They joined Nvth the

firm of Todd & McGill to send a cargo of goods into the west in 1769,

but the Rainy Lake Indians plundered it and would not permit the traders

to go further. A year or two later a second attempt was made with

greater success. Joseph Frobisher seems to have been in charge of the

venture, and he tells us that Fort Bourbon was reached. We are told by

others that he had a trading post, called Frobisher's Fort, at some

point on the Red

River, probably in the winter of 1771-2. We are also told that he went

north to Hudson Bay in the summer of 1772, that he met the Indians at

Pike (Jackfish) River soon after as they went north to trade at Fort

Prince of Wales and induced them to sell their furs to him regardless of

their obligations to the Hudson's Bay Company, and that in 1771 he was

at Trade Portage, which lies 011

the route connecting the North Saskatchewan with the Churchill. There he

secured such an immense quantity of furs that he had a clear profit of

£10,000 on the

cargo which he took to Montreal. During the summer of 1775 Thomas

Frobisher explored the country west of Trade Portage as far as Lake He a

la Crosse, but his older brother does not seem to have returned to the

west, although he took an active interest in the fur trade for many

years.

The

amazing success of Curry and Finlav could not fail to incite the other

traders to greater ventures in the far west. So we find that Alexander

Henry, whose enterprises on the shores of Lake Superior had not proved

very remunerative, left Michilimackinac on June 10, 1775, with twelve

small canoes and goods worth £3,000, and took the route of the old

French voyageurs to the western wilds. Late in July he reached the site

of la Verendrye's fort at the outlet of Rainy Lake, and on the 30th he

reached the Lake of the Woods. He crossed the Portage du Rat on August

4, descended the Winnipeg River, following the Pinawa channel, and

halted at a Cree village near the old French fort, Maurepas. On August

18 he set out on the voyage of three hundred miles down Lake Winnipeg,

and before it was completed, he had been joined by another trader, Peter

Pond. They reached Jackfish River on September 1 and on the 7tli were

overtaken by Joseph Frobisher, his brother Thomas, and another trader

named Patterson. The combined parties numbered one hundred and thirty

men with thirty canoes. They entered the Saskatchewan on October 1,

reached Lake Bourbon (Cedar Lake) on the 3d, and the site of the present

Pas Mission on the 6th, finding a band of Wood Crees encamped there. On

October 26 they reached Cumberland House, near Sturgeon Lake, the fort

which Hearne had built for the Hudson's Bay Company about a year earlier

to divert the Indian

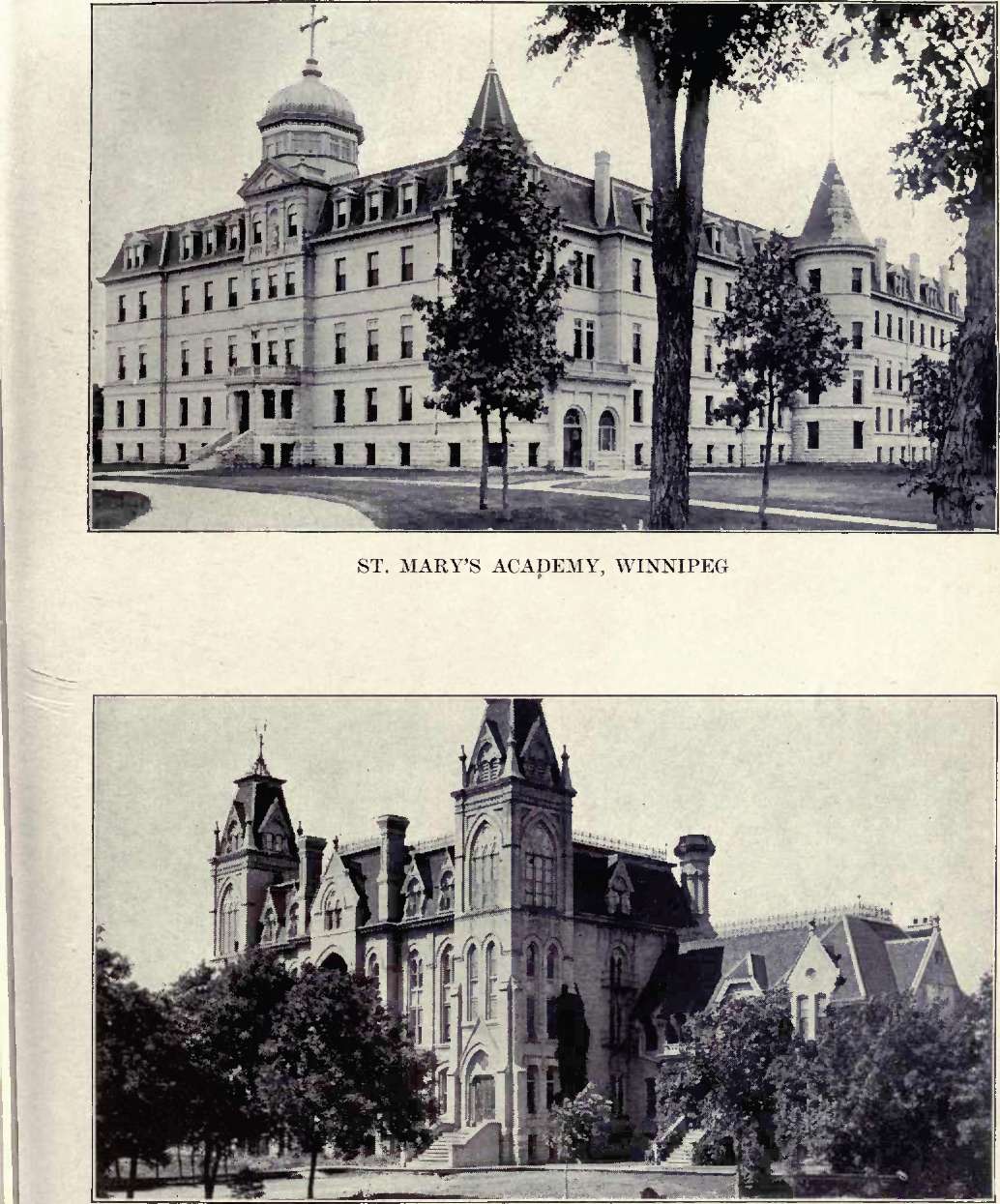

ST. JOHN'S COLLEGE, WINNIPEG.

trade of that district to the bay. The post was garrisoned by Orkneymen

under the command of Mr. Cockings. Being at the junction of the canoe

routes to the north and the west, it soon became one of the most

important posts of the company.

At

this point the traders separated, having divided the territory so that

each would practically' have a monopoly of the trade of the district to

which he went. Gadotte went with four canoes to Fort des Prairies (Nipawi)

not far from the forks of the Saskatchewan; Pond look two canoes to Fort

Dauphin beside Lake Manitoba; while the Frobishers with six canoes and

Henry with four went westward and camped for the winter at Beaver Lake.

On New-Year's Day, 1776, Henry and Joseph Frobisher set out for

Cumberland House, and after a short stay there, went west on a long trip

of exploration. The snow was deep, the cold was severe, and their

provisions were soon exhausted. For several days they had nothing in the

way of food except water in which k little chocolate had been dissolved;

and had they not been fortunate enough to find a deer frozen in the ice

of the river, they would have perished from starvation. Finally they

reached Fort des Prairies, where they remained several days. Leaving the

hospitality of the fort, the two hardy travelers wandered far across the

Saskatchewan plains, hoping to find new bands of Indians whose trade

they might secure. At last they met a party of Assiniboines and were

conducted to their village, where they were well entertained until the

20th of February. Then they returned to Fort des Prairies, where they

stayed for four weeks, and, continuing their journey to their own post,

reached it on the 9th of April.

Three days later Thomas Frobisher was dispatched with six men to build a

post on the Churchill River, where the Indians could be intercepted on

their way to Fort Prince of Wales. The rest of the party remained to

fish until May 22, when it followed the advance detachment. On June 15

it reached the fort which Frobisher had erected, and on the next day a

small party was sent forward toward Lake Athabasca to find a certain

tribe of Indians with whom the traders wished to establish friendly

relations. They met these Indians coming down to the post, and all

returned together. The Indians had brought down great quantities of fur,

and a brisk trade was soon going on. Henry says, ''On the third morning

this little fair was closed; and, on making up our packs, we found that

w_e had purchased twelve thousand beaver skins, besides large

numbers of otter and marten." Leaving Thomas Frobisher in charge of the

unsold goods, Henry and the elder Frobisher then set out on their return

journey and reached Montreal on October 15. Their venture had been so

successful that neither of these men had any need to return to the west.

Peter Pond, who spent the winter of 1775-6 near Port Dauphin, passed the

next two years on the Sturgeon River, probably near Fort Saskatchewan.

He went north to Lake Athabasca in 1779 and remained in the vicinity for

several years. This was a district to which Canadian traders had not

penetrated before, and Pond's post beside the Elk River was a wel1

known landmark for some time. He went there as the representative of

several traders, who had united in the venture - and stored goods in

this post in 1779 to he used in the next year's trade, thus imitating in

a small way the practice of the large companies. Pond was far more

successful than his principals had anticipated, and in 1780 a new supply

of goods was sent out in charge of Mr. Wadin, who was to act as Pond's

colleague. The two men soon quarreled, and Wadin was shot and died from

the wound. Bond and his clerk were tried in Montreal for the murder, hut

were acquitted.

The

remarkable success of such men as Henry and Frobisher drew an

ever increasing crowd of

traders into the west, and many of them were simply unprincipled

adventurers. A party of such men had crossed from the Saskatchewan River

to the Eagle Hills in .1780. Annoyed by an Indian's repeated requests

for liquor, one of these men gave him laudanum. The savage dropped dead

a few minutes later, and his friends took swift vengeance on his

murderer. When the skirmish was over the trader and six of his men were

killed, and the others were glad to escape with their lives, leaving

their goods in the hands of the enraged Indians. There was trouble at

two of the posts on the Assiniboine during the same season. Both posts

were attacked by the hostile. Indians, and several men, both white and

red, were killed. The Montreal traders gave the natives poorer goods

than they had formerly received from the Hudson's Bay Company, and often

crazed them by giving them the vilest kind of liquor in large

quantities.

The

hostility of the Indians, which had been provoked by the unscrupulous

methods of the white traders, might have resulted in a long series of

atrocities, had it not been for a terrible epidemic of smallpox. In the

summer of 1781 a band of Assiniboines went to the Mandan country to

procure horses and brought back the disease which has always proved so

fatal to Indians. It spread with great rapidity among the tribes living

west and north and prevailed for two years. At the end of that time many

thousands of the natives were dead, the fur trade was almost destroyed,

and nearly all the traders had fled from the country.

When the fur trade was resumed after this interruption, it was conducted

on a new plan. The individual trader, taking a small quantity of goods

so far and meeting the competition of traders like himself, found the

enterprise hazardous and expensive; and he was helpless against the

hostility of the Indians. The plan adopted by Henry and his

fellow-traders in the winter of 177o had shown the value of

co-operation, and Joseph Frobisher and Simon McTavish were busy carrying

the idea a little further. During the winter of 1783-4 they organized

the North-West Company to carry on the fur trade in the west. In the

spring McTavish and Benjamin Frobisher went to Grand Portage and

persuaded nearly all the traders congregated there to join the new

company; hut Peter Pond and Peter Pangman, both New Englanders, were not

satisfied with the terms offered by McTavish, and they organized another

company whose leading members were John Gregory, a merchant of Montreal,

and his partner, Alexander Norman McLeod.

The

North-West Company was very energetic and ambitious. In a memorial

presented to Governor Haldimand in October, 1784, it recites the

discoveries it had made and the benefits it had conferred on the country

in less than a year, and asks that it may be granted a monopoly of the

old French route from Lake Superior to Lake Winnipeg for ten years, a

perpetual monopoly of a new route which it was about to open between the

two lakes, and a monopoly of the trade in the remote west for ten years.

It also asked for the privilege of building its own ships for carrying

goods and furs up and down the Great Lakes.

The

fact that these requests were refused did not deter the company from

pushing its business with great energy.

Nor

was the opposing company less ambitious or less energetic. McLeod was

left in charge of all its business in Montreal, and most of the other

partners took charge of districts in the west. Alexander Mackenzie was

sent to the Churchill River to compete with "William McGillivray whom

the North-West Company had sent there as its representative; and when

they came out together in 1786, both had been very successful. Ross was

sent to Lake Athabasca, Pangman went to the Saskatchewan, Roderick

McKenzie was ordered to lie a la Crosse, Pollack had charge of the Red

River district. Not content with opposing its rival in nearly every

district in the west, the new company established a post of its own at

Grand Portage.

The

unprincipled Pond soon deserted the company he had helped to organize

and was sent by the North-West managers to oppose Ross in the Athabasca

district. He immediately stirred up a bitter strife between his own men

and those of his rival, and in one of their conflicts Ross was killed.

Pond was arrested and sent east, and thereafter he plays no part in the

story of the fur companies. These and similar troubles hastened the

amalgamation of the two companies which was consummated in 1787. McLeod,

McTavish, and the Frobishers were the principal directors of the new

company in Montreal. Alexander Mackenzie was sent to take the place of

Ross on Lake Athabasca, and the information which came to him there led

him to the explorations that afterwards made him famous.

Between 1789 and 1793 Mackenzie followed to the Arctic the great river

which bears his name and crossed the mountains to the Pacific. These

splendid achievements brought him fame and promotion; but after a few

years he disagreed with his partners and retired from the North-West

Company. The arbitrary methods of McTavish had alienated many of the

other shareholders, and these men, led by Sir Alexander Mackenzie,

organized the new North-West Com -pany, more commonly know n as the X.

Y. Company. For three years the keenest rivalry existed between the two

companies, each sending agents into new and remote districts and

building forts wherever possible; but their keen competition does not

seem to have reduced the profits of either. Simon McTavish died in 1804,

and this made a reunion of the companies possible. An agency was

established in London, and business in the Canadian west was pushed more

energetically than ever before. The independent traders having been

taken into the reunited North West Company or driven from the field, it

could give all its strength to its contest with the Hudson's Bay Company

for the control of the fur trade in British America.

The

fur trade, as conducted by the French companies of Quebec, had bred a

class of men who were almost indispensable in carrying it on when it

passed into the hands of the British merchants of Montreal. These men

were Frenchmen, adventurous, fond of the free, roving life of the

voyageur or the

coureur des hois, and ready to adopt the life

of the aboriginal inhabitants of the forests and the plains. Many of

them took Indian wives, and in time a considerable number of French

half-breeds enlisted in the calling followed by their fathers. The

independent traders employed many of these men, and it was only natural

for the North-West Company to retain their services when it absorbed the

business of the individual traders. In his letter to Governor Haldimand,

dated October 4, 1784, Joseph Frobisher says that the North-West Company

then employed more than five hundred of these men in the transportation

of goods, furs, and provisions, about half being engaged on the Great

Lakes and the other half in the interior It required more than ninety

canoes in its operations between Montreal and the Lake of the Woods.

Those used on the Great Lakes were manned by eight or ten men and

carried about four tons; but those employed in the interior would carry

only about one and a half tons. The canoes with goods for -he more

distant posts left Montreal in May, carrying provisions to last their

crews to Michilimakinae, Here they took on a new supply to meet the

needs of the canoemen on the inland trip and provide some food for the

men in charge of the interior posts. On the inland trip about one third

of the cargo would be provisions and the remainder goods for the Indian

trade. Sir Alexander Mackenzie tells us that by the end of the century

the company employed twelve hundred canoemen, fifty clerks, seventy-one

interpreters and clerks, and thirty-five guides.

No

small share of the success of the North-West Company was due to the

character of the men in charge of its posts in the west. Some of the

company's bourgeois, or partners, and its clerks may have been men of

low morals and vicious lives, and they may have often resorted to the

most unscrupulous methods in trade; but almost without exception they

were men of wonderful energy and determination. And there were some men

of ideals higher than large cargoes of fur and great profits. Perhaps

the first place must be given to Sir Alexander Mackenzie, but high honor

is also due to men like David Thompson and James Finlay. Of the

incessant activity of the bourgeois, whether Scotch, English, French, or

Metis, we have abundant evidence in the records of the company and the

journals of its employees, such as Harmon and the younger Henry.

Daniel William Harmon entered the service of the North-West Company in

the year 1800, being twenty-two years of age at the time. In April of

that year he was sent west from Montreal and travelled by the usual

route to Lake Winnipeg. There he received orders from Alexander N.

McLeod, who had charge of the trade of the surrounding district, to

proceed to a point west of Lake Manitoba where a new post was to be

opened. He explored the country around this lake, establishing friendly

relations with the Indians as far as possible. The winter was spent at a

fort on the Swan River, and the spring found him at Fort Alexandria. The

next two years were spent between the posts at Swan River and Bird

Mountain and Fort Alexandria; but in the spring of 1804 Harmon went on

to Fishing Lake and thence to Last Mountain Lake, The remainder of that

year was spent on the Qu'Appelle River, at Fort Dauphin, and on the

Assiniboine.

In

the spring of 1805 Harmon was on the Souris. and later in the year went

down the Assiniboine and the Red, visited Rainy Lake, and by September

was at Cumberland House, where he remained nearly two years, trading

with Crees, Assiniboines, Chippewas. and a few Blackfeet, Midsummer of

1807 saw him at Fort William, whence he went to the Nepigon for the

balance of the year. In the next year he was sent west again, visiting

the posts at Rainy Lake, Bas de la Riviere, Cumberland House, Beaver

Lake, Portage, du Traite, lie a la Crosse and elsewhere. September found

him at Fort Chippewayan on Lake Athabasca, October at Fort Vermillion,

and the winter at Dunvegan Fort in the remote west where he remained

until October, 1810. Then he went to St. John's Fort on the upper Peace

River with. Mr. Stuart and. crossed the Rocky

Mountains into British Columbia. For three years he worked at various

posts in the heart of the mountain region and did not return to Dunvegan

until Mareh of 1813. But a month later he went back to the mountains

once more and spent the next six years of his life at different posts

there. It was August, 1819, when Harmon reached Fort "William on the

last of his long trips. lie had spent nineteen years in almost incessant

travel among trading posts scattered over half a continent and was ready

to retire from the service of the company and spend his remaining years

with his Indian wife and their children in his quiet home in Vermont.

Alexander Henry the younger was a nephew of that Alexander Henry who

went to the Saskatchewan with the Frobishers in 1775. His life does not

command our respect as does that of Harmon, but it was just as full of

activity, change, and strange experiences as that of his fellow

bourgeois in the North-West Company. His first winter in the west, that

of 1799-1800, was spent at Fort Dauphin beside Lake Manitoba. In the

spring he went down to Grand Portage and was sent, back with goods for

the trade along the Red River. The autumn and winter were spent at

various points along the river and its branches as far south as Grand

Forks. The temper of the Indians appears to have been very uncertain,

and there was some danger of war between the different tribes; so Henry

does not seem to have thought it wise to establish any permanent posts

in the district. He showed himself more than a mere trader however, for

he procured a stallion and a mare which were sent to Mr. Grant at a post

on Rainy River, probably the first horses in that region, and at some

place on the east side of Red River he planted potatoes from seed

obtained at Portage la Prairie.

A

few years later we find Henry in charge of various posts in the

Saskatchewan district, and then he is sent further and further west—to

Vermillion, Terre Blanche, and Rocky Mountain House. Then follow some

years at posts beyond the mountains, and finally his death by drowning

in the mouth of the Columbia during the spring of 1814. |