|

The

Earl of Selkirk had scarcely completed the purchase of his great western

domain before he issued an attractive prospectus of the new colony and

instructed his agents to enlist settlers for it. Captain Miles Macdonell,

whom Lord Selkirk had met in Upper Canada seven years earlier, was

brought over to take charge of the first party of colonists. He was sent

to seek recruits in Ireland, Captain Roderick McDonald was at work in

Glasgow, while Colin Robertson strove to persuade the needy Highlanders

that comfort and happiness awaited them on the western prairies.

Captain Macdonell had to contend with many difficulties, and most of

them had their source in the hostility of the North-West Company to

Selkirk's colonization scheme. In a letter to the earl Macdonell says,

"I have learned that Sir Alexander Mackenzie has pledged himself so

opposed to the project that he will try every means in his power to

thwart it.'' Simon McGillivray, who acted as the North-West Company's

agent in London, wrote to his partners in Montreal, on June 1, 1811,

"Mr. Ellice and I will leave no means untried to thwart Selkirk's

schemes, and being stockholders of the Hudson's Bay Company, we can

annoy him and learn his measures in time to guard against them." The

North Westers were as good as their word. To counteract the inducements

held out to colonists by Lord Selkirk's agents several articles appeared

in Scottish news papers declaring that his lordship's motives were most

mercenary and painting in dark colors the dangers and hardships of

pioneer life in such a remote region as Rupert's Land.

Three vessels were made ready for the voyage to Hudson Bay. The

Eddystone and the

Prince of Wales were to carry freight and the

servants of the Hudson's Bay Company, but most of the settlers were to

go on the Edward

and *Anne, a poor vessel manned by a poor

crew. The little flotilla sailed from London in June and proceeded north

to pick up its passengers. Heavy weather drove them into Yarmouth

harbor, and while waiting there, Macdonell purchased a few small cannon

for the defence of his colony. These diminutive pieces of artillery come

into the story of the settlement on several occasions. Sailing north

again, the Prince

of Wales stopped at Stromness in the Orkneys

to allow some of the company's employees to come on board, while the

other vessels went on to Stornoway in the Hebridean island, Lewis, where

most of the emigrants were waiting. About seventy-six settlers and

fifty-nine clerks were to be taken out. Many of the clerks came from

Glasgow, but most of the settlers came from the Highlands or from

Ireland.

There seems to have been little enthusiasm in the party, and some of

that little oozed away under the influence of a discouraging pamphlet

circulated among :hem. the doleful predictions of friends, the petty

annoyances of customs officials, and the obstacles put in their way by

agents of he North-West Company. A few were induced by clever recruiting

officers to enlist, and several deserted

from the ships, some going in such haste that their clothing was left on

board Finally Macdonell could write to the earl, "All tfie men we shall

nave are now embarked, but it has been a Herculean task-.** Even then

his troubles were not quite ended, for on July 26 a Captain Mackenzie,

posing as an officer of the law, rowed out to the

Edward and Anne to read the Emigration ict

and to ask if every one on board was going away of his own free will.

But a round shot, dropped over the ships side, went through the bottom

of his boat and compelled him to pull for the shore in hot haste. He

promptly challenged the captain to a duel for this insult to his

dignity; but Miles Macdonell would not delay his departure for such a

paltry matter. A breeze sprang up

hi the evening,*and

about eleven o'clock Macdonell gave orders to leave the port. As the

Edward and Anne weighed anchor, a man dropped

overboard and swam to the shore; and two others would have been left

there, if Robertson had not bundled them into a boat and rowed them out

to the vessel just as she was making sail. One wonders if any of her

passengers would have remained on board, if they could have foreseen all

the hardships which awaited them; but this they could not do, and so

shortly before midnight the vessels left the harbor, bearing the

pioneers of three great provinces to their future homes. The midnight

sailing of the colonists on July 26, 1811, was a historic occasion, but

no demonstration marked it;

even the customary salute from departing ships was omitted, so anxious

was Captain Macdonell to leave the port where he had endured so much

annoyance.

As

there was danger from French ships cruising in the North Atlantic, the

government sent a man-of-war to protect the

Edward and Anne and her consorts until they

were some hundreds of miles west of Ireland; then she returned, and they

continued their voyage without protection. The weather was not

favorable, and the voyage lasted sixty-one days. Macdonell tried to

relieve its monotony by auction sales of deserters' clothing, games, and

military drill. The drill was not very successful, and the men in

Macdonell's party did not seem likely to prove very efficient protectors

of their settlement, if it were ever attacked, or very successful

hunters, if it were necessary to depend on game for food. He says, "I

had some drills of the people with arms: but the weather was generally

boisterous, and there were few days when a person could stand steady on

deck. There never was a more awkward squad—not a man, or even officer,

of the party knew how to put a gun to his eye or had ever fired a shot,;1'

One of the men, named Walker, openly opposed the drills, declaring that

the colonists were going out as free settlers, not as soldiers of the

Hudson's Bay Company; and others fomented discontent by arguing that

neither Lord Selkirk nor the company had a valid title to the land on

which it was proposed to place them, inasmuch as the French and the

North-West Company had prior rights in the country.

By

September 6 the ships were in Hudson Strait, and soon they were sailing

across the bay towards their destinations. The

Eddystone was laden with goods for Churchill

Harbor, but was unable to reach her destination. She went on to York

Factory with her sister ships, and the three vessels anchored off that

port on September 24. As soon as possible the colonists were landed on

the tongue of land which lies between the Hayes and Nelson rivers. Snow

was falling and the thermometer registered 8° below zero. No

preparations had been made to receive the party, and it was too late in

the season to attempt the journey of seven hundred miles to the district

intended for the colony; and many of the settlers must have wished that

they had listened to the advice of Northwest agents at Stornoway.

Macdonell found that the fort was "poorly constructed and not at all

adapted for a cold country." So on October 8 the settlers were taken

across the strip of land between the two rivers to a point on the Nelson

some miles above its mouth and sheltered in tents until they could build

that collection of cabins, afterwards known as the "Nelson Encampment,"

in which they passed the winter.

By

the end of October the rough cabins, sheltered from the prevailing winds

by the high bank of the river, were ready for occupation. They were

constructed of logs about a foot in diameter, the interstices between

them being tilled with clay and moss and the sloping roofs being covered

with the same material. The floors were of logs roughly hewn, bunks

served as bedsteads, and the other furniture was home-made and scanty.

Twigs and moss took the place of mattresses, and buffalo robes and

coarse blankets served for bedclothing. The comfortable homes which the

people looked for were still a long way off.

The

men were kept busy during the winter, some hunting, others drawing

provisions from the fort. Macdonell took wise precautions against

scurvy; and while there was some sickness, no deaths occurred. On

Christmas day he gave his people a dinner; and on New Year's day Mr. W«

II. Cook, the company's factor at the fort, sent them a generous supply

of strong drink that they might keep the day in accordance with the

customs of the country. This was unfortunate, for it resulted in a tight

between the Irishmen and the Glasgow men that night and many sore heads

the nest morning.

There was a good deal of latent discontent among the people, and some

declared that they were under no obligation to obey Captain Macdonell.

On February 12 one man flatly refused to do the work assigned to him. It

was necessary to maintain some sort of discipline, and so Macdonell had

him confined in a hut; but fourteen of the Glasgow men broke into the

hut during the night, released the prisoner, and then burned his prison.

When they were brought before Mr. Hillier, the magistrate, they showed

their contempt for his authority by walking out of the court-room.

Macdonell was puzzled to know what course was best in such cases, for

legislation adopted by the home government and the government of Canada

had left it very uncertain what power was entrusted with the maintenance

of order in Rupert's Land; but Messrs. Cook and Auld of the Hudson's Bay

Company had lived in the lawless land long enough to have learned

effective methods of dealing with turbulent characters. So the fourteen

Glasgow men were expelled from the encampment, and their supply of

provisions was stopped. This compelled them to go down to the fort and

purchase provisions at their own cost. When spring came and the other

members of the party were preparing to go south, the insubordinate men

were ready to submit to Captain Macdonell's orders; but he believed that

prevention is better than the cure and refused to allow those who bad

caused so much trouble during the winter to go to the Red River. Some of

them were employed in the company's factories on the coast, others were

assigned to more western posts, and a few were sent back home.

During the winter a few men had been employed in building boats, and

when spring arrived, four were ready for use. They were twenty-eight

feet long and proved to be very heavy and somewhat unmanageable, but

they served their purpose. Macdonell had a poor opinion of the ability

of his people as boat-builders. The ice on the Hayes River broke up in

May, and all the settlers were moved across to its banks in readiness

for the journey south; but the ice continued to run for a long time, and

while the people waited, the Saskatchewan fur brigade came down. When

this party had stored its furs in the company's warehouse and set out on

its return trip, the settlers went with it. It was the 6th of July when

they started on their toilsome journey inland.

Seven hundred miles lay between the settlers and the homes which they

hoped to secure. For nearly four hundred miles their route led up rapid

rivers and through an absolute wilderness, and in all their forecasts of

the journey these Scotch and Irish people could never have imagined the

experiences through which they would pass before they reached its end.

As the idle onlooker watches skilled Indian or half-breed boatmen manage

a heavy York boat, the work seems simple enough. It is fascinating

too—the muscular bodies rising and falling in time with some monotonous

chant, the regular swing of the heavy oars as they propel the boat,

through the foaming water, the dextrous movements as it is poled up a

shallow, the straining file of trackers as it is towed up a heavy rapid,

the hurried unloading when a landing is made, the swift rush across a

portage with incredible loads, the quick reloading; but to the

colonists, all unused to such work, it was the most wearing toil. Only

unlimited hope and courage could have led them forward.

Pushing oft' into the swift Hayes River, the voyagers slowly made their

way up it for about fifty miles, rowing and tracking by turns. Then the

stream divided, and they followed its western branch, the Steel River,

through a beautiful valley for nearly thirty miles more. Its banks are

high, but they afford a better footing for trackers than the banks of

the lower river do. The eastern branch of this stream, called the Hill

River, is a swift river, with many shallows and rapids, and its banks

are very steep, sometimes rising to a height of ninety feet. Beyond them

the country is studded with wooded hills, and many small lakes nestle in

the intervening valleys. Rowing, tracking, and poling by turns,^ the

settlers made their way up this stream for sixty miles. At Rock Portage,

the river bed, is divided into narrow channels by several small islands,

and the water rushes down them in beautiful falls and cascades. Beyond

Mossy Portage the river widens out into Swampy Lake whose still waters

gave the men a partial respite from their arduous toil. So did Knee Lake

and Oxford Lake still further up the stream. On these expanses it was

possible to hoist sails sometimes so that favorable breezes would give

the weary rowers a chance to rest.

Beyond Oxford Lake they pushed up the narrow gorge between precipitous

cliffs, known as nell Gates, and then on through a chain of small lakes

and connecting streams until at Painted Rock Portage they reached the

summit of the slope drained by the Hayes River. They were seven hundred

feet above their

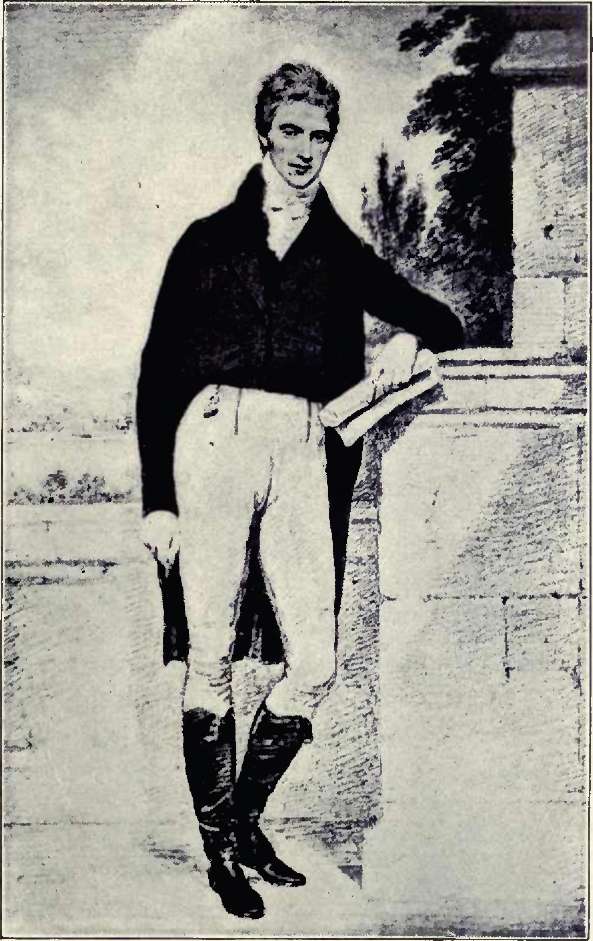

THOMAS, EARL OF SELKIRK

starting point at its mouth, and the hardest part of the trip was

accomplished. Crossing the portage, they followed the Rehemamish River

to Hairy Lake, went down Blackwater Creek to an arm of the Nelson River,

and ascended it to Lake Winnipeg. Skirting the shore of the lake, and

rowing and sailing by turns, they made their way southward and in time

reached the mouth of the Red River. To follow it to its junction with

the Assiniboine was comparatively easy, and on August 30, 1812, the

little band of colonists, utterly worn but still hopeful, reached their

destination. It was a year and thirty-five days after they left

Stornoway.

No

preparation had been made for the weary travellers, and this seems a

serious oversight on the part of Lord Selkirk; but it is difficult even

now to make Old Country people understand conditions in new prairie

provinces, and it would have been quite impossible at that time when

there were no settlements at all in the prairie country. However, the

few people living in the neighbor hood gave the new arrivals the kindly

welcome which seems characteristic of the frontier. They received a warm

reception from the Highlanders employed in the North-West Company's

fort, and a few of them were housed in the company's buildings. Some

were taken into the homes of a few retired servants of the companies who

lived in the vicinity, and the others were sheltered in tents. A party

of Indians and Metis made a warlike demonstration when the

unsophisticated strangers arrived, but this was probably no more than a

rough practical joke.

It

is likely that Captain Macdonell would have located his settlement on

the west side of the Red River close to the Assiniboine, if that site

had not been occupied by Port Gibraltar, built by the North-West Company

about seven years earlier. As it was, he selected a site nearly two

miles further down the river at the base of that triangle of land known

as Point Douglas, many of his people being encamped on the opposite bank

of the Red in the meantime. As soon as possible, he allotted to each man

a plot of ten acres on the site which he had selected and made

preparations for the erection of small houses on these plots. The small

village thus formed was called Colony Gardens. A little further down the

west bank of the river farms of about one hundred acres were granted to

the settlers, each having a frontage of ten chains on the river and

running back about a hundred chains.

There were no oxen or working horses in the country, and no farm

implements except spades and hoes; and it was too late to put in any

crop that season, if teams and implements had been available. There was

no grain in the country, and few vegetables were grown at that time. The

agents of the Hudson's Bay Company at Brandon House had been ordered to

send down a supply of pemmiran for the settlers, but they had failed to

do it; so Captain Macdonell purchased such provisions for them as the

North-Westers in Port Gibraltar could supply, and Lord Selkirk paid the

bills, as he had agreed to furnish his colonists with food for a certain

time. We are told that four cows, a bull, a few pigs, and some poultry

were also purchased for the colony by Selkirk's agent during the next

few months. These animals had been brought from Canada at great expense.

The

ceremony of taking formal possession of Lord Selkirk's domain occurred

on September 4. Invitations to attend the function had been sent to the

partners and clerks of the North-West

Company, to the time-expired servants of the fur compares who had

settled in the neighborhood, to the colonists, and the Indians. The

ceremony took place on some spot now included m the site of St.

Boniface. The central figure of the group which gathered there was Miles

Macdonell the representative of the Earl of Selkirk, who was attended by

a small armed guard - Mr. Hillier represented the Hudson's Bay Company,

while its rival was represented by John Willis, Alexander McDonell, and

Benjamin Frobisher, the travel-worn colonists gathered around, and Metis

and Indians were interested spectators. By Macdonell's directions the

instrument which gave Lord Selkirk a title to his great territory was

read and parts of it translated by Mr Heney for the benefit of the

French, and then Macdonell took possession in the name of the earl.

Flags were unfurled, and a salute was fired from the small cannon

brought from Plymouth. A keg of spirits was broached for the people, the

gentlemen retired to Captain Macdonell's tent for refreshments, and the

ceremony was ended.

The

Red River Settlement was founded, and a new page in the history of the

west was turned. Thenceforward it was to be an agricultural country, not

a mere hunting ground; farmers rather than trappers and fur traders were

to determine its destiny. We do not know all the motives which urged the

colonists forward during the thirteen weary months of their .journey and

the weary months of privation which followed it. It may have been hope,

a spirit of adventure, dogged obstinacy, indifference, or sheer

desperation. Having once> embarked on the enterprise, they bad little

chance to turn back. It is true that a few who reached York Factory were

not allowed to go further, and that Father Bourke,. the Roman Catholic

priest who had been selected by Captain Macdonell to minister to the

spiritual needs of his co-religionists, remained at the factory to wait

for a ship which would take him back to Ireland. Mr. Edward, the medical

man who had accompanied the party to York, does not seem to have gone

further, and probably it was not intended that he should; but of the

others all who had the chance to go on to Red River seem to have done

so. Most of them were young. Of eighteen men whose names are given us

only three were over thirty years of age, and all except three are set

down as "laborers." One of the three is called a boat builder, another a

carpenter, and the third an overseer. There are Scotch names in the

roster of the party—Campbell, McKay, McLennan, Bethune, Wallace, Cooper,

Harper, Isbister, and Gibbon. Six of their owners came from Ross-shire,

Argyle-shire, and Ayr-shire, but the last four belonged to the Orkney

Islands. And from Sligo, Kiilalla, and Crosmalina in Ireland came

Corcoran, McKim. Green, Gunn, Jordan, O'Rourke, McDonell, and Toomey.

These unknown laboring men, whose great ambition was to make homes of

their own on the frontier of a vast wilderness, were real

empire-builders. The rest of the world may not have known about them nor

eared; but because they went on doing their best under the most adverse

conditions, they were true heroes. The wonderful development of a

century helps us to appreciate the great debt which Manitoba owes to

these humble pioneers, and appreciation of their work will continue to

grow with the passing years. |