|

The

dissatisfaction of the people of the Red River Settlement with the form

of government under which they lived, their sense of the injustice of

some of the laws of the Hudson's Bay Company, and their lack of respect

for the courts which it had established had been shown again and again,

notably in the Sayer trial. While the demonstration against the company

on that occasion was con lined to the French and Metis, these had the

sympathy of nearly all the in habitants of the colony in their efforts

to break the company's monopoly.

The

results of that trial were soon apparent. There was an immediate in

crease in the number of independent traders doing business in all parts

of the settlement. Furs were soon included in the articles bought and

sold by these traders, and expeditions were fitted out by them and sent

to distant parts of the country to trade with the Indians. In 1861 Mr.

Andrew McDermott sent two boats laden with goods into the distant

interior, and three other private merchants sent out one boat-load each.

The Hudson's Bay Company no longer invoked the aid of the law against

these competitors, but it tried to compel them to quit the field by

employing all the advantages which a great corporation has over rivals

possessing small means. 'Nevertheless the independent traders prospered

and multiplied.

Perhaps the trade which showed the most remarkable growth was that

between the Red River Settlement and the towns of Minnesota. It had been

inaugurated by the half-breeds, who found in these towns a market for

the surplus products of the buffalo hunt after the small demand at Fort

Garry had been supplied. A large part of this business remained in their

hands for many years; and even when the goods exchanged were bought and

sold by whites, the work of freighting them north and south was done

almost entirely by half-breeds. For years the transportation over this

route was done by carts drawn by oxen or ponies, and after a time the

same method of transportation was adopted in sending goods to distant

points west of Fort Garry. Thus freighting became an important industry

in the colony. At one time no less than 1,500 carts were employed

between Fort Garry and St. Paul, and on this route and the western

routes nearly 700 men were employed.

As

facilities for transporting merchandise from the Atlantic seaboard to

Minnesota improved, a larger percentage of the goods used by the people

of Red River was brought into the colony by the Minnesota route; and in

time the Hudson's Bay Company itself imported a good deal of its

merchandise by this route rather than by the way of York Factory. Soon

the volume of trade had increased to such an extent that better means of

transportation than the Red river cart became necessary, and steamers of

light draft were built and launched upon the Red River. The Hudson's Bay

Company seems to have been the leading promoter of this new enterprise.

The first of these steamers, the

Anson Xorihrup,

was launched upon the Red River in 1859, and started on her initial trip

to Fort Garry on June 3rd. A larger steamer, the

International, was built in 1861. She was one

hundred and fifty feet long, drew only forty-two inches of water, and

her registered tonnage was one hundred and thirty-three tons. She made

her first trip from Georgetown to Fort Garry in seven days and arrived

at the latter place on May 26, 1862. Among her passengers were the

family and servants of Governor Dallas, Mr. John Black who was to act as

recorder of the colony, the bishop of St. Boniface and a number of his

clergy, and about one hundred and sixty people from Canada, most of whom

intended to take the overland route to the Cariboo gold-fields. But the

length of the

International made her less useful than her

builders hoped she would be, and in dry seasons the water in the river

often became too low for any steamer to make the trip up or down; so the

building of river steamers did not entirely deprive the half-breed

freighters of their occupation.

The

energy of the people of the Red River Settlement was bringing the colony

into closer touch with the rest of the world, and at the same time

explorers were traversing the country and carrying to other lands

information in regard to its wonderful resources. Lieut, Franklin,

afterwards Sir John Franklin, with Dr. Richardson and a party of

assistants, explored the northern part of what is now Manitoba during

the summer of 1819 and spent the following winter on the Saskatchewan.

Then he went down the Coppermine and spent nearly two years exploring

the Arctic coast, He passed through Red River again in 1825. The

expedition sent by the United States government in 1823 under Major

Stephen Long and Mr. "Win. II. Keating, a geologist, to determine the

exact position of the international boundary from the Lake of the "Woods

westward, furnished much exact information about the district which it

traversed, and the two volumes from Mr. Keating's pen which embody it

are full of interest. An expedition sent out by the British government

in 1831 under Capt. George Back passed through Red River on its way

north to search for Capt. John Ross and his party.

In

1836 the Hudson's Bay Company fitted out an exploring expedition,

putting Mr. Thomas Simpson and Mr. Peter W. Dease in charge of it, and

sent it north and west from Fort Garry-. In 1842 Lieut. Henry Lefroy was

sent out from England to make a scientific survey of Rupert's Land. He

landed at Montreal, travelled to Fort Garry by 1he old canoe route of

the fur traders, and after a careful examination of the Red River valley

and the shore of Lake Winnipeg, went down to York Factory. Having

explored a part of the coast of the bay, he returned to Norway House and

passed up the Saskatchewan. He wintered at Fort Chippewayan and

afterward went on to the west and north. The British government sent

several expeditions north by way of Red River in the long search for the

lost Franklin party, which sailed from England in 1845 and never

returned. The expedition, which was sent out under Capt. John Palliser

in 1857 for the exploration of Rupert's Land, spent some time in Red

River Settlement on its way west. In the same year the Canadian

government sent a party under Mr. George Gladman. with Prof. Henry Hind

and Mr. S. J. Dawson as assistants, to make a careful survey of the

country around the Red River Settlement. Its work occupied nearly two

years. In the year 1859 Mr. Robert Kennicott of the Smithsonian

Institute went to the Yukon in search of scientific, information and

returned by the way of Red River in 1862. In the same year Viscount

Milton and Dr. Cheadle passed through the settlement on their

adventurous journey through the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific.

The

reports of these explorers and other visitors from the outside world,

who carried information about the Red River country to their homes,

helped to bring new settlers to the colony, and by 1866 its population

must have been nearly ten thousand. The growing population, the

increased trade, the greater ease of communication with the outside

world by a route to the south, all tended to render the colony less

dependent on the Hudson's Bay Company and to make the people more eager

for self-government. And yet events happened occasionally which showed

that the colony must still rely on the company for help in times of

stress.

The

fair treatment which the Indians all over the country had received at

the hands of the company and their dependence upon it must have helped

to secure for the settlers immunity from the depredations of the

savages; and the frequent visits of parties of Sioux from Minnesota

might have had calamitous results for the colony, if these restless and

excitable red men had been treated less kindly and less wisely by the

company's officials at Fort Garry. It spent many hundreds of pounds in

feeding these unwelcome visitors from the south and prevented

complications which might have made serious trouble for both Great

Britain and the United States; and yet, in several eases, neither

government reimbursed it for the outlay.

"When misfortune overtook the settlement, the Hudson's Bay Company stood

ready to aid the suffering people; and such occasions were not

infrequent. There was a bad food in the spring of 1852. On May 7th the

water in the Red River rose eight feet above the high water mark of

ordinary years. The first rise took place in the night, ami the houses

of the settlement were surrounded by water before the occupants were

aware of the danger which threatened them. Soon the country for three

miles on either side of the river was inundated. At first the people

took refuge in the upper rooms of their houses and on stages hastily

constructed; but as the water continued to rise, they were forced to

abandon these places of refuge for the few points in the neighborhood

whose elevation kept them above the flood. By the 12th of the month half

the settlement along the river was under water, and for twenty-two miles

along the stream every house was submerged, and all fences and loose

material had been swept away. By the 22nd the flood was at its highest,

being only one and a half feet lower than the bad inundation of 1826.

About 3,500 people had to leave their homes and flee to the open

country, where they had few tents, a small quantity of fuel, and an

insufficient supply of food. Fortunately only one person was drowned.

But many horses, cattle, and pigs were drowned before they could be

conveyed to places of safety, and some dwellings, barns, and

outbuildings were swept away, as well as most of the farmers' carts and

lighter implements. The total loss was estimated at £25,000. It was June

12th before the people could return to their homes, and then it was too

late to sow wheat, although some barley was sown and some potatoes were

planted. Mr. Colville, the governor, did everything in his power to

alleviate the sufferings of the people, and in this he was cordially

assisted by the clergymen of the settlement.

The

colony recovered from this disaster more quickly than might have been

expected. Bishop Anderson, writing of this flood and comparing it with

that of 1826, says:

"Though there is greater suffering and loss, there ;s greater

elasticity and power to bear, as also larger means to meet it. In 1826,

the settlement was then in its infancy, there were but few cattle; a

single boat is said to have transported all in the middle district m one

forenoon; now each settler of the better stamp has a large stock. The

one whose record of the first flood we had read at home, who had then

but one cow, has now, after all his losses, fifty or sixty head. Then,

too, there was but little grain, and the pressure of want was felt even

when the waters were rising. Their dependence throughout was on the

scanty supply of fish or what might be procured by the gun. Now there is

a large amount of gram in private hands, and, even with the deduction of

the laud which is this year rendered useless, a far larger number of

acres under cultivation. In this light it is comparatively less severe;

the whole of the cultivated land was then under water, and nearly all of

the houses carried off by it. It was, as many have called it, a cleaner

sweep. But there were then few houses or farms below the middle church

or on the Assiniboine above the upper fort; the rapids and the Indian

settlement were still in the wildness of nature. In 1826, a larger

number of those who were unattached to the soil and without ties in the

country left the settlement. Since that a large population has sprung up

who are bound by birth to the land and look to it as their home, whose

family ties and branches are spread over and root themselves in its very

soil, making a happy and contented population proud of the land of their

birth. Compared with the flood of 1826, the flood of 1852 will occupy a

larger space in the public mind. Instead of a few solitary settlers,

unknown and almost forgotten by their fellowmen, they are now parts of a

mighty system linked by sympathy and interest to other lands."

In

1861 there was another flood, although it w-as not so destructive as

that which devastated the settlement nine years earlier. It led to a

great scarcity of grain in the following year. Mr. Joseph J. Ilargrave

says,'"The spring of 1862 was a period of starvation in Red River

Settlement. Daily dozens of starving people besieged the office of the

gentleman in charge at Fort Garry, asking for food, and later in the

season for seed wheat, By a grant of eight hundred bushels of wheat,

allowed by the Governor and Council of Assiniboia, the bulk of the

poorer classes wTere supplied with seed and grain to feed

them until, with the spring, the means of gaining a livelihood became

available/'

In

1862 there was a fairly good crop, although some damage was done by a

hail-storm in August. In the following year the crops were greatly

injured by a severe drought, and the prices of produce were very high in

consequence. Wheat sold for 12 shillings per bushel and flour for 30

shillings per hundred-weight. The summer of 1861 was also very dry and

very hot. The

International could make but one trip during

the season owing to low- water. Ilargrave says, "The drought prevailed

until the middle of July, when rain for the first time visited the

parched ground. With it, unfortunately, arrived

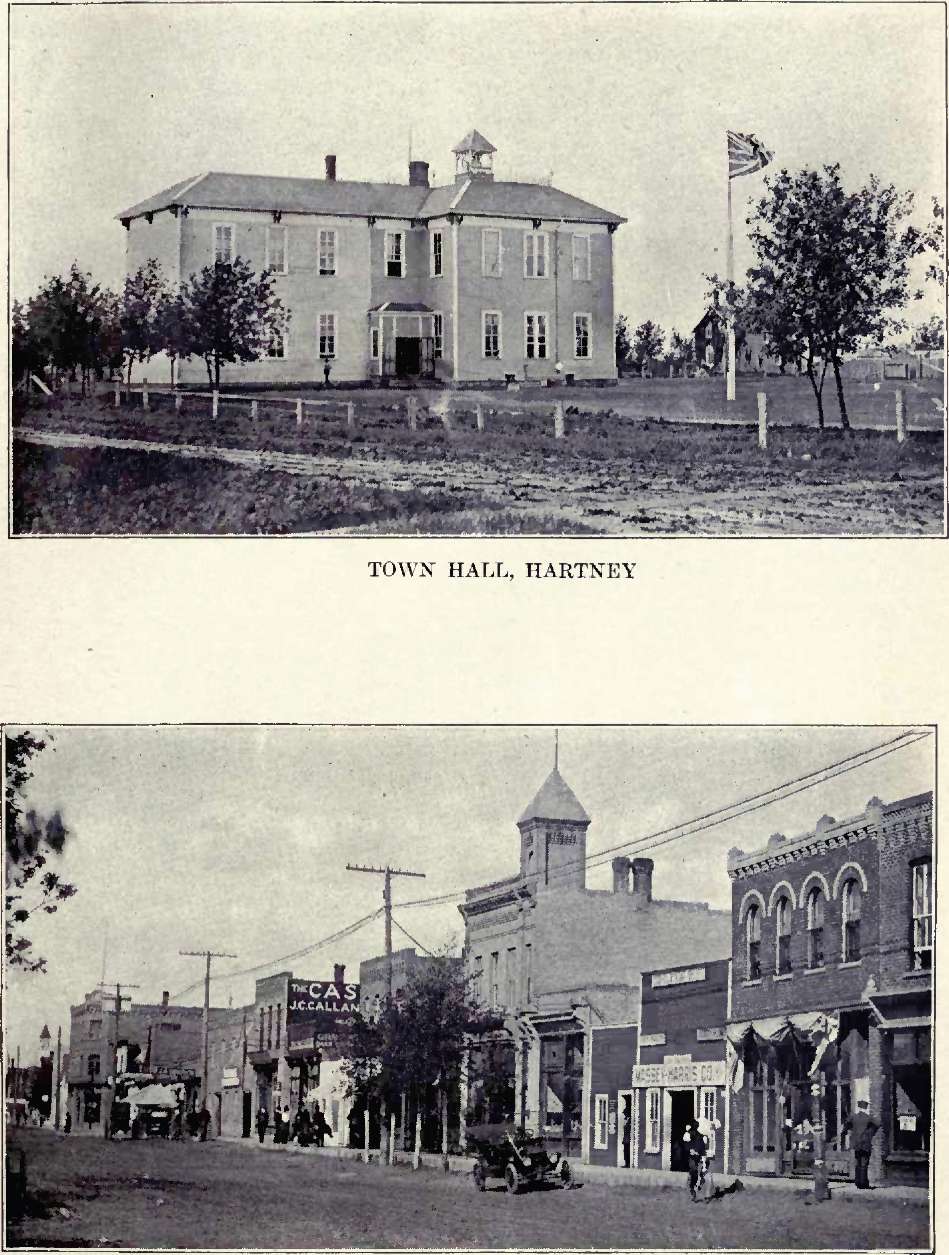

MAIN STREET, HARTNEY

swarms of locusts (grasshoppers) which with terrible voracity cleared

away the rising crops.

The

stock, property, and rights of the Hudson's Bay Company had been sold to

a new, Corporation in 1863; but the new company retained the name,

traditions, and, to a great extent, the methods of the old company. Its

relations to the settlers were much the same as those of the older

organization had been. Two of its ships were wrecked in Hudson Bay

during 1864, the cargo of one being an entire loss while that of the

other was a partial loss. For this reason the company had to bring more

than the usual amount of freight over the Minnesota route. As Hargrave

says:

"The mischief done by the grasshoppers spoiled the harvest, but the

fisheries and the plain hunts continued to supply the people with food,

and the low water in the river, which had prevented the steamboat

running, necessitated the employment of a vast number of Red River carts

by the Company's freight contractors, thus supplying the numerous

settlers possessed of moderate means, who owned the vehicles, with

profitable employment during summer for themselves and their cattle.

Indeed, the mishaps which hitherto prevented the working of this steamer

proved great windfalls to the people. In former times the freight, which

now comes by St. Paul, passed to its destination by the York route, and

the cash disbursed in purchasing its transport between the bay and the

settlement, being paid to the Red River tripmen who worked the boats,

circulated m the colony, while the sums disbursed to the St. Paul

contractors of late years have been paid in bills of exchange on the

Board of the Company in London, which, being negotiated in the United

States, cut off a large outlet of the local cash currency formerly

flowing from the Company's strong box. The St. Paul contractors, being

unable to run the steamer, were compelled to engage freighters at Red

River to travel to Georgetown, there to meet the goods brought thither

from St. Paul by their own people, over that portion of their freight

route intended, at' the time of arranging the terms of their contract,

to be traversed by land carriage. Large importations of grain were

brought from Minnesota, and the local duty thereon was repealed by the

Council of Assiniboia. In consequence of these circumstances anything

approaching a famine was averted.''

An

unusual misfortune befell the colony in 1865. Typhus fever had been

brought to York Factory some time before by passengers who came out on

the Prince of

Wales, and from that port the deadly disease

spread south to the Red River Settlement and carried off a large number

of the people during the summer. During the spring swarms of

grasshoppers again swept over the settlement, doing great' damage to the

young crops; but the season was a favorable one, the harvest was much

greater than had been anticipated. In 1866 the crops were unusually

good, although the grasshoppers did some damage in restricted areas.

In

the autumn of 1867 the whole country was overrun by swarms of

grasshoppers, which deposited their eggs everywhere. When these eggs

were hatched in the spring, the young insects devoured everything green

and completely ruined the crops. Starvation threatened the colonists,

for not only w-ere the crops destroyed, but the buffalo hunt failed, few

fish could be caught, and small game disappeared. The outlook had not

been darker for many years; but appeals for aid made by the local

newspaper and the press of Canada and letters on the situation from the

Earl of Kimberley and others which appeared in the London

Times met with a generous response, and aid

was sent from all sides. The Council of Assiniboia immediately came to

the assistance of the colonists, voting £600 for the purchase of seed

wheat, £500 for flour, and £500 for the purchase of ammunition, twine,

and hooks to be given to the settlers who wished to use them in

procuring game and fish. The Hudson's Bay Company sent £2,000 from

London, and private benefactors in England sent £1,000 more. The

government of Ontario voted $5,000 for the relief of the sufferers, and

the private contributions from various parts of Canada were most

liberal, while people in the United States gave $5,000 to help their

neighbors north of the boundary line through a year of scarcity. A

committee, composed of the governor, the bishops, and a number of the

other prominent residents, was organized to distribute the supplies. As

the flour and other food supplies for the distressed settlers had to be

brought from St. Paul, many of them were given employment in hauling

these provisions across the prairie, the freight being paid in supplies

for their families. This work kept them busy until the early part of the

new year. |