|

In

1858 the British government decided to make Vancouver Island a crown

colony, and the secretary of state for the colonies instructed Governor

Douglas to call an assembly of representatives of the inhabitants to

devise some form of government for it. The license of the Hudson's Bay

Company, giving it the exclusive right of trade on the island, was not

renewed in 1859; and the governor, acting on instructions from Downing

Street, proclaimed the revocation of the license and the establishment

of a new province of the British Empire. This action of the imperial

authorities gave fresh courage to the opponents of the company's

government in Rupert's Land and raised the hopes of the people of Canada

who wished to see that vast region annexed to their own provinces.

The

Canadian government was not satisfied with the report of the select

committee of the British House of Commons, presented in July, 1857. It

was especially disappointed that no effective steps had been suggested

by the committee for settling the boundary between Canada and the

territory of the Hudson's Bay Company on the north and the west and that

there had been no investigation of the company's charter. It regarded

the validity of the charter as a fundamental matter in the whole

question at issue between the company and Canada. The position taken by

the government of Canada was shown m the following clause of a joint

address of the Assembly and the Legislative Council presented to Her

Majesty in August, 1858: "That Canada, whose rights stand affected by

that charter, to which she was not a party, and the validity of which

has been questioned for more than a century and a half, has, in our

humble opinion, a right to request from Your Majesty's Imperial

Government, a decision of this question, with a view of putting an end

to discussions of conflicting rights, prejudicial as well to Your

Majesty's Imperial Government, as to Canada, and which, while unsettled,

must prevent the colonization of the country."

On

September 4 of the same year the Executive Council of Canada addressed a

communication to Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton. the secretary of state for

the colonies, drawing attention to the importance of having a direct

line of communication by railway or otherwise between Canada and the

valleys of the Red and Saskatchewan Rivers, and later in the year

Messrs. Cartier, Ross, and Gait went to England in connection with the

matter. While there they intimated that Canada would take legal steps to

test the validity of the charter of the Hudson's Bay Company, and the

colonial secretary appears to have advised the governor-general of

Canada that he approved of such a step; but His Excellency replied on

April 19, 1859, that his council did not advise such action.

The

imperial government made it plain in many ways that it would favor some

practicable plan whereby the territory of the Hudson's Bay Company would

be annexed to Canada. Shortly before the license of the company expired

in May, 1859, Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton offered to renew it for one year

or two years over the district east of the Rocky Mountains, pending some

"arrangement" with

Canada. But the company refused on the ground that a renewal for such a

short period would only increase the inconvenience which had resulted

from the state of suspense in which the question had been kept for two

years, and that it would paralyze the company's authority in its own

territory by creating an impression that the authority would shortly

terminate. When the license was finally renewed for the usual period of

twenty-one years, the government suggested that the question of the

Canadian boundary should be referred to the privy council; but it

refused to let the validity of the company's charter be tested while the

boundary proceedings were pending, and so the Canadian government

declined to take any part in the matter, on the ground that it could not

be expected to compensate the company for any territory until the

company's right to such territory was established.

On

March 9, 1859, Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton wrote to the governor of the

Hudson's Bay Company, urging that the company come to some friendly

arrangement with the Canadian government; but the directors do not seem

to have taken any steps to carry out his suggestion. He then decided

that he would have the validity of its charter tested by the judicial

committee of the privy council but before this could be done, the

government of which he was a member went out of office.

The

new government tried at intervals during 1860 and 1861 to devise a bill,

satisfactory to all parties, whereby the imperial government might

acquire from time to time portions of the territory of the Hudson's Bay

Company for colonization, making suitable compensation therefor.

Presumably these portions were to be transferred to Canada. But the

company objected to this piece-meal dismemberment. Canada objected to

acquiring the territory in such a manner, and no method of making

compensation to the company was devised; and so the whole scheme came to

naught.

In

April, 1862, the Canadian government sent a communication to Governor

Dallas of the Hudson's Bay Company, desiring to make some arrangement

for the construction of a road and a telegraph line through the

company's territory so as to connect Canada with British Columbia. Mr.

Dallas replied that, while the question was really one for his board of

directors in London, he himself thought that the request could not be

granted. Such works as were proposed and such chains of settlements as

were expected, if established in the valleys of the Red and Saskatchewan

Rivers, would soon drive the buffalo away from these districts and so

cut off the supply of food by which the company was able to maintain its

trading posts in the regions further west and north. He believed that

partial concessions of the company's territory in this way would

inevitably lead to its extinction, and that, if any change were made in

the government of such districts, direct administration by the crown was

the only method likely to give public satisfaction. His letter contains

the following paragraph: "I believe I am, however, safe in stating my

conviction that the company will be willing to meet the wishes of the

country at large by consenting to ail equitable arrangement for the.

surrender of all the rights conveyed by the charter;.-'

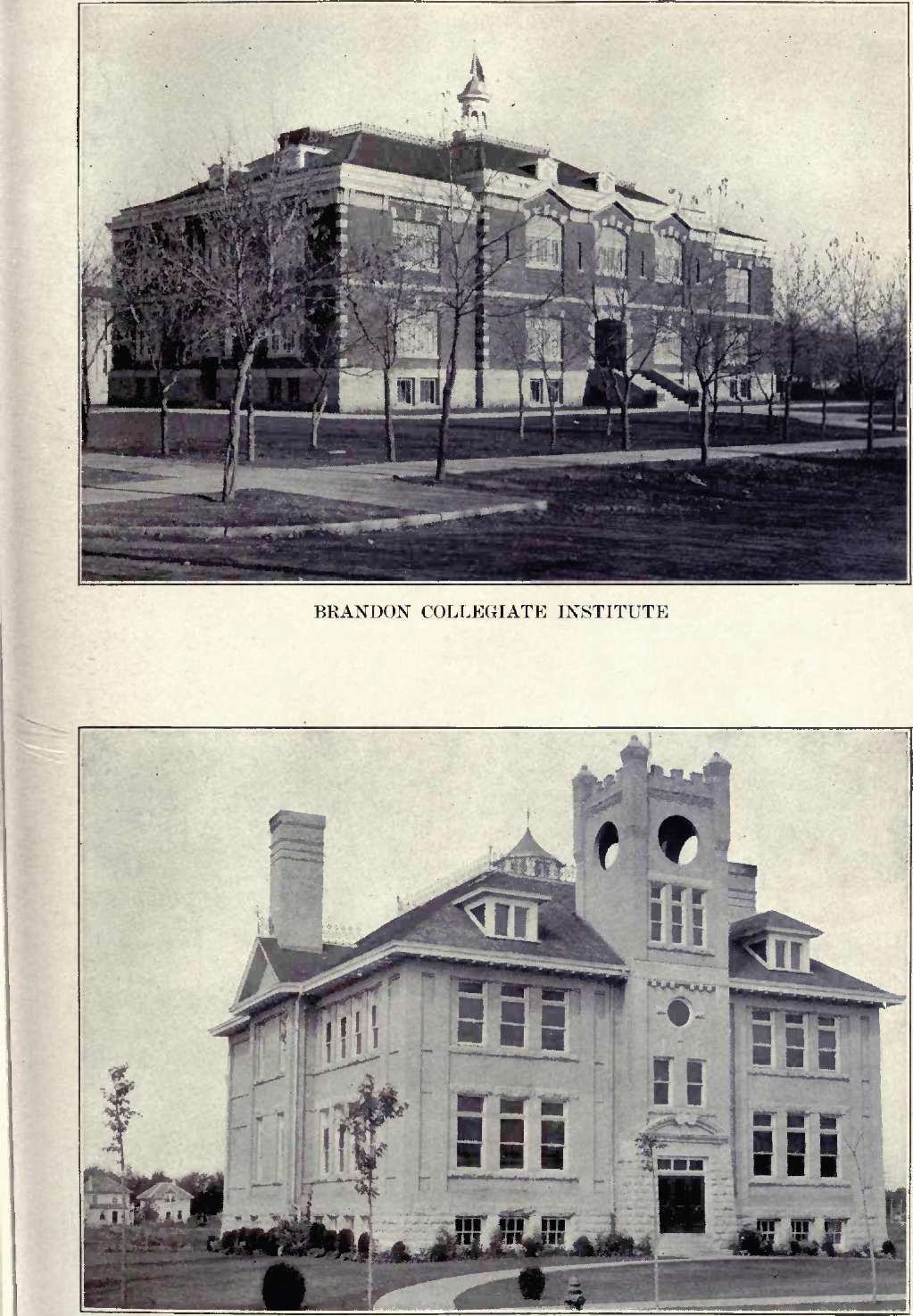

COLLEGIATE INSTITUTE, PORTAGE LA PRA1RIK

During the summer of 1862 Mr. Edward Watkin, a gentleman who had been

prominently connected with the Grand Trunk Railway, went to England,

hoping to interest capitalists there in a scheme for building a road and

a telegraph line across central Canada. In the autumn of the same year

the Canadian government sent Messrs. Howland and Sicotte to London to

urge upon the home government the importance of opening up the Hudson's

Bay Company's territory for settlement; anil they, working with Mr.

Watkin. succeeded in interesting several prominent Englishmen in their

plans. The unwillingness of the company to have the road built, the

unwillingness of the imperial government to grant a subsidy for the

work, and the unwillingness of the Canadian government to give any

substantial aid, so long as the boundaries of the company's territory

were undetermined and its title in doubt, were obstacles too serious to

permit Mr. Watkin's scheme to be carried out.

The

simplest solution of all the difficulties would have been the purchase

of the rights of the company by the imperial government; but if was

unwilling to take this step, and so another solution was sought. Mr.

Watkin succeeded in organizing a new company, and securing the necessary

capital for it, to buy all the stock, lands, rights, and other property

of the Hudson's Bay Company. The sum paid the old company was

£1,500,000, and for this amount it transferred all its property to the

International Finance Association, which in turn transferred it to the

new company whose capital was fixed at £2,000,000. The final transfer

was consummated in July, 1863^ and Mr. Watkin at once proceeded to

Canada to secure government aid in his plans for opening up the western

prairies by building roads, constructing telegraph tines, and planting

settlements. His proposals were not favorably received by the

government, for it found that the new company maintained all the

territorial claims of the old one, and it declined to grant the aid

asked for until the validity of those claims was definitely settled. The

reply of the Executive Council to Mr. Watkin's proposal concludes thus:

The committee therefore recommend that correspondence be opened with the

Imperial Government, with the view to the adoption of some speedy,

inexpensive, and mutually satisfactory plan to determine the important

question (that of territorial rights of the company and that the claims

of Canada be asserted to all that portion of Central British America,

which can be shown to have been in the possession of the French at the

period of the cession in 1763.

In

November of that year Sir Edmund Head, governor of the Hudson's Bay

Company, declared that the most- satisfactory solution of the difficulty

would be. the purchase of all the company's territory by the crown• but

as there were many obstacles in the way of such a plan, he proposed an

alternative scheme. By it the territory fit for settlement would be

equally divided between the crown and the company, with the exception of

certain specified tracts to be retained by the latter; the road and

telegraph would be constructed by the company; the crown would purchase

such premises of the company as were needed for military purposes; and

it would pay the company one third of the revenue derived from gold and

silver in the territory acquired.

The

proposals made by Sir Edmund Head on behalf of the Hudson's Bay Company

did not meet with the approval of the Duke of Newcastle, the colonial

secretary, and in the spring of 1864 he made the following

counter-proposals to the company:

"1.

That within certain geographical limits the territorial rights of the

company should he surrendered to the Crown;

"2.

That the sum of 1s. per acre on every acre sold by the government should

be paid to the company, and payment 1o cease when their aggregate

receipts from this source shall exceed £150,000, or on the expiration of

50 years;

"3.

That one-fourth of the sum received by the government as an expert duty

for gold, or on leases of gold mines, or licenses for gold mining, shall

be payable to the company for 50 years, or until the aggregate receipts

shall amount to £100,000;

"4.

That on these conditions a government be established in. the ceded

territory, Great Britain undertaking the expense and risk of that

government until the colony is able to support it, as in British

Columbia and other colonies.'^

The

directors of the company met on April 13, 1864, and decided to accept

the general principles underlying the duke's proposals, although they

desired some changes in the details. They urged that the payments for

land and minerals should be placed at £1,000,000 instead of £250,000, or

else that they should not be limited in time, and that the company

should receive 5,000 acres of land for each 50,000 acres sold by the

crown. On June 6 Mr. Cardwell, who had succeeded the Duke of Newcastle

-as colonial secretary^ informed the company that he could not entertain

the amendments it had suggested, and no further progress in the

negotiations was made for six months. But in December the directors of

the company met to reconsider the matter, and the result was an offer to

accept £1,000,000 as payment in full for the territory mentioned, which

was practically all that granted by the charter of Charles II.

In

opening the Canadian parliament on Feb. 10, .1864, Lord Monek, the

governor-general said, "The condition of the vast region lying on the

northwest of the settled portions of the province is daily becoming a

question of great interest. I have considered it advisable to open

correspondence with the Imperial Government, with a view to arrive at a

precise definition of the geographical boundaries of Canada in that

direction. Such a definition of boundary is a desirable preliminary to

further proceedings with respect to the vast tracts of land in that

quarter belonging to Canada, but not yet brought under the action of our

political and municipal system." The position taken by the Canadian

government, thus referred to in the speech from the throne, was stated

in plainer terms by Hon. William McDougall in the debate which followed.

He believed that Canada was entitled to all that part of the North West

Territory, which could be shown to have been in possession of the French

when they ceded Canada to the British.

In

these prolonged negotiations, these proposals and counter-proposals,

several facts are evident: the desire of the Hudson's Bay Company to be

relieved from the task of government and its willingness to sell its

vast territory for adequate remuneration; the desire of the home

government to effect- a friendly settlement of the questions at issue

between the company and Canada, to find some method for transferring the

company's territory to Canada, and to keep the question of the company's

title in abeyance; and Canada's steady adherence to the position that

the questions of title and boundaries should first be settled. It will

also be apparent that the three parties were gradually approaching

common ground for the settlement of the questions at issue between them.

Early in 1865 the Canadian government sent a delegation headed by lion.

George Brown to London to make one more attempt to secure the transfer

of the territory of the Hudson's Bay Company to Canada. The delegates

discussed the matter with Hon. Mr. Cardwell, and his statement of their

position and that of his government is as follows: ''The Canadian

ministers desired that that territory should be made over to Canada, and

undertook to negotiate with the Hudson's Bay Company for the termination

of its rights, on condition that the indemnity, if any should be paid,

would be raised by Canada by means of a loan under Imperial guarantee.

With the sanction of the Cabinet, we assented to the proposal,

undertaking that if the negotiations should be successful, we, on the

part of the Crown, being satisfied that the amount of the indemnity was

reasonable and the security sufficient, would apply to the Imperial

Parliament to sanction the arrangement and guarantee the amount."

Nothing further, however, seems to have been done for several months;

but in February, 1866, Sir Edmund Head informed Mr. Cardwell that

certain Anglo-American capitalists were likely to submit an offer for

the purchase of all the arable land of the Hudson's Bay Company with a

view to colonizing it: and, when he was reminded by the colonial

secretary that there was an understanding between the Canadian delegates

and the home government that Canada would have the first opportunity to

secure the territory if the company disposed of it, Sir Edmund replied

that the company could not be expected to leave the offer to Canada open

for an indefinite period to its own financial detriment. These views

were communicated to the Canadian government, and it replied on June 22

that while it recognized the importance of completing the negotiations

for the extinction of the territorial claims of the company, the

annexation of the territory to Canada, and the establishment of a

regular government therein, the matter seemed one for the government of

the Dominion of Canada to settle; and as the confederation of the

provinces would shortly be accomplished, it hoped that the final

settlement might be deferred a little longer. It also expressed the hope

that Her Majesty's government would use its influence in the meantime to

prevent any such sale as that contemplated. This reply was conveyed to

the company, and six months later Lord Carnarvon suggested to the

company 1hat. it would not be wise to take any steps which would

interfere with the negotiations with Canada.

The

confederation of the Canadian provinces became an accomplished fact on

July 1, 1867; and thereafter it was the Dominion of Canada, instead of

the united provinces of Ontario and Quebec, with which the home

government and the Hudson's Bay Company had to deal in the negotiations

for the transfer of the company's territory. While the delegates of the

different provinces were working out the details of the confederation

scheme, they passed a resolution, fully endorsing the position taken by

the Canadian government in its communication to the imperial government

on the 22nd of the preceding June; and in framing the British North

America Act, by which the Dominion of Canada was created, its framers

anticipated the early transfer of the territory of the Hudson's Bay

Company to the Dominion, for Article XI, sec. 146, provided as follows :

"It shall be lawful for the Queen, by and with the advice-of Her.

Majesty's Most Honorable Privy Council, etc., on addresses from the

Houses of the Parliament of Canada, to admit Rupert's Land and the

North-West Territory, or either of them. into the Union, on such terms

and conditions in each case as are in the addresses expressed, and as

the Queen thinks fit to approve, subject to the provisions of this Act."

The

statesmen of the new Dominion were fully alive to the importance of

securing its vast hinterland in order that it might soon become a united

dominion from the Atlantic to the Pacific, and the matter came up during

the first session of its first parliament. On December 4, 1867, Hon.

William McDougall, minister of public works, introduced a series of

resolutions on which the addresses referred to in the British North

America Act were to be based. These resolutions, which discreetly kept

Canada's old contention in the background, created much discussion; but

after a few amendments, they were adopted in the following form:

"1.

That it would promote the prosperity of the Canadian people, and conduce

to the advantage of the whole Empire, if the Dominion of Canada,

constituted under the provisions of the British North America Act of

1867, were extended westward to the shores of the Pacific Ocean.

"2.

That colonization of the fertile lands of the Saskatchewan, the

Assiniboine, and Red River districts, and the development of the mineral

wealth which abounds in the regions of the North-West, and the extension

of commercial intercourse through the British possessions in America

from the Atlantic to the Pacific, are alike dependent upon the

establishment of a stable government, for the maintenance of law and

order in the North-Western Territories;

"3.

That the welfare of a sparse and widely scattered population of British

subjects of European origin, already inhabiting these remote and

unorganized territories, would be materially enhanced by the formation

therein of political institutions bearing analogy, as far as

circumstances will admit, to those which exist in the several provinces

of this Dominion;

"4.

That the 146th section of the British North America Act of 1867 provides

for the admission of Rupert's Land and the North-Western Territory, or

either of them, into union with Canada, upon terms and conditions to be

expressed in addresses from the Houses of Parliament of this Dominion to

Her Majesty, and which shall be approved of by the Queen in Council^-"

"5.

That it is accordingly expedient to address Her Majesty, that she would

be graciously pleased, by and with the advice of Her Most Honorable

Privy Council, to unite Rupert's Land and the North-Western Territory

with the Dominion of Canada, and to grant to the Parliament of Canada

authority to legislate for their future welfare and good government.

"6.

That in the event of the Imperial Government agreeing to transfer to

Canada the jurisdiction and control over this region, it would be

expedient to provide that the legal rights of any corporation, company,

or individual, within the same, will be respected; and that in case of

difference of opinion as to the extent, nature, or value of these

rights, the same shall be submitted to judicial decision, or be

determined by mutual agreement between the Government of Canada and the

parties interested. Such agreement to have no effect or validity until

first sanctioned by the Parliament of Canada.

"7.

That upon tlie transference of the territories in question to the

Canadian Government, the claims of the Indian tribes to compensation for

lands required for purposes of settlement would be considered and

settled in conformity with the -equitable principles which uniformly

governed the Crown in its dealings with the Aborigines.

"8.

That a select committee be appointed to draft a humble Address to Her

Majesty on the subject of the foregoing resolutions."

The

Hudson's Bay Company would not consent to the transfer of its territory

until the amount of compensation for it hail been settled, and as Canada

had practically agreed to do this, the Duke of Buckingham and Chandos,

then secretary of state for the colonies, sent a dispatch to Lord Monck,

saying that the Dominion government must settle the terms of the

transfer with the company before the bill authorizing the transfer would

be submitted to the imperial parliament. Accordingly the Dominion

parliament passed the Rupert's Land Act in .Tulv, 1868, authorizing the

government to acquire the territory of the Hudson's Bay Company. The

government sent Sir George E. Cartier and Hon. William McDougall to

England to arrange terms with the company, and they sailed on their

mission on October 3, 1868. Soon after they had presented their

credentials to the Duke of Buckingham, that minister informed them

rather pointedly that the company was to be treated as a proprietor

holding a good title to the lands whose transfer was sought, and so

eliminated Canada's old contention from the discussion. There were

proposals and counter-proposals for some time; and the business was also

delayed by a change of government, in which Earl Granville succeeded the

Duke of Buckingham in the colonial office, and by the resignation of the

Earl of Kimberley, the company's governor, who was succeeded by Sir

Stafford Northcote.

The

British government was most anxious to have the negotiations brought to

a satisfactory termination, and Earl Granville seems to have brought

some pressure to bear upon the company, just as his predecessor had done

upon the representatives of Canada. He plainly reminded the company that

the title to its great territory was not beyond dispute, that its

boundaries were open to question, that its vast domain was almost

certain to be overrun by thousands of Canadian and American settlers,

that it was powerless to prevent such an invasion, and that its

government of the great region in the past had not proved its ability to

maintain law and order there for the future. Finally an agreement was

reached, and on March 9, 1869, the arrangements for the transfer were

completed. They were as follows:

"1.

The Hudson's Bay Company to surrender to Her Majesty all the rights of

government, property, etc'in Rupert's Land, which are specified in 31

and 32 Victoria, clause 105, se«tion 4; and also all similar rights in

any other part of British North America not comprised in Rupert's Land,

Canada, or British Columbia,

"2.

Canada is to pay to the Company £300,000 when Rupert's Land is

transferred to the Dominion of Canada.

"3.

The Company may, within twelve months of the

surrender, select a block of land adjoining each of its stations, within

the limits specified in Article 1.

"4.

The size of the blocks is not to exceed........ acres in the Red River

country, nor three thousand acres beyond that territory, and the

aggregate extent of the blocks is not to exceed fifty thousand acres.

"5.

So far as the configuration of the country admits, the blocks are to be

in the shape of parallelograms, of which the length is not more than

double the breadth.

"6.

The Hudson's Bay Company may, for fifty years after the surrender, claim

in any township or district within the Fertile Belt, in which land is

set out for settlement, grants of land not exceeding one-twentieth of

the land so set out. The blocks so granted to be determined by lot, and

the Hudson's Bay Company to pay a rateable share of the survey expenses,

not exceeding an acre.

"7.

For the purpose of the present agreement, the Fertile Belt is to be

bounded as follows: On the south by the United States boundary) on the

west by the Rocky Mountains; on the north by the northern branch of the

Saskatchewan ; on the east by Lake Winnipeg, the Lake of the Woods, and

the waters connecting them.

"8.

All titles to land up to the 8th of March,

1869, conferred by the Company, are to be confirmed/

"9.

The Company to be at liberty to carry on its trade without hindrance, in

its corporate capacity, and no exceptional tax is to be placed on the

Company 's land, trade, or servants, nor an import duty on goods

introduced by them previous to the surrender.

"10. Canada is to take over the materials of the electric telegraph at

cost price, such price including transport, but not including interest

for money, and subject to a deduction for ascertained deterioration.

"11. The Company's claim 1o land under agreement of Messrs. Vankoughnet

and Hopkins to be withdrawn.

"12. The details of this arrangement, including the rilling up of the

blanks in Articles 4 and 6, to be settled by mutual agreement."

Such were the terms on which the government of the Hudson's Bay Company

ceased, after it had been an empire within the empire for two hundred

years; thus it surrendered its title to most of a territory out of which

half a dozen European kingdoms might have been carved; and thus Canada

acquired a vast addition to her dominion whose estimated area was nearly

two and a half millions of square miles. The long-deferred hopes of the

people of the Red River colony for stable self-government and the

maintenance of law and order were on the eve of being realized. |