|

The

terms under which the Hudson's Bay Company agreed to transfer its

territory to the Dominion of Canada were finally settled on March 9,

1869; the necessary order- in-council, endorsing these terms, was

adopted by the imperial government; on June 22, 1869, the parliament of

Canada passed an Act for the Temporary Government of Rupert's Land and

the North-West Territory; and October 1, 1869, was the date fixed for

the payment of the purchase price of £300,000 and the completion of the

transfer.

But

the transfer was not to be made without disturbance, and to understand

the causes of the disturbance many facts must be kept in mind. Some of

these facts relate to the Hudson's Bay Company and the position in which

it found itself, some to the actions of the Canadian government, some to

the attitude of the Canadian people, and others to the attitude of the

Red River people themselves, The facts in connection with these matters

are patent to any one who studies the existing circumstances carefully.

It has been vehemently affirmed and as vehemently denied that other

influences, hidden but strong, were at work, fanning the smoldering

embers of suspicion and dissatisfaction among the people of Red River

until they broke out in the flame of open rebellion; but the advocates

of neither side seem to have proved their case, and we must wait for

time to give a verdict which will embody the whole truth.

The

year 1869 found the officers of the Hudson's Bay Company in the Red

River Settlement in a very difficult position. The company's rule was

about to terminate; and as soon as the actual transfer of its territory

was made, they would cease to have any authority as government

officials. The company's influence as a governing body had been moribund

for several years, and it died when the terms of the transfer were

settled; yet its officials were expected to maintain law and order in a

land where all their authority had vanished. The actual transfer was not

accomplished as soon as was expected, and in the meantime no new

governing machinery could be put in motion and the country was without a

real government of any sort. These facts should be remembered,

especially by those who have criticised Mr. William Mactavisb, the

company's governor at Fort Garry, for inaction and vacillation. It

should be remembered, too, that Governor Mactavish was ill, and that,

much against his will, he remained in office until the transfer was

completed.

For

the blunders of the Dominion government it is less easy to find valid

excuses. Before any act had been passed or any agreement adopted, which

would give it a title to any part of the territory of the Hudson's Bay

Company, even before the terms of the transfer had been settled, it had

taken steps, which assumed in a practical way the ownership of the Red

River country. On September 18, 1868, Hon. William McDougall instructed

Mr. John A. Snow to proceed to Red River and commence 1he construction

of a road from the settlement to the Lake of the Woods along the route

recommended by Mr. S. J. Dawson some ten years earlier. This was done

without any formal understanding with the Hudson's Bay Company. Mr. Snow

claimed that he had received verbal permission from Governor Mactavish

to commence the work; but this does not seem to have been approved by

the directors of the company, for during the negotiations which Messrs.

Cartier and McDougall conducted during the autumn and winter of that

year, the directors made a formal complaint to the colonial secretary

because the Canadian government was constructing a road across the lands

of the company without its permission.

The

conduct of some of the men sent to carry out the undertaking was unwise,

that of others most reprehensible. The majority of the laborers engaged

on the road were Canadians or Americans; few of the Metis secured

employment, although they were in special need of the wages to be earned

in that way because of the ravages of the grasshoppers during the

preceding summer. The Metis of the settlement were greatly irritated by

a series of private letters written by one of Mr. Snow's assistants to

friends in Canada who were indiscreet enough to give them to the Toronto

Globe for publication. These letters

contained some severe criticism of the French half-breeds, and they

afterwards made the writer feel their resentment in an unmistakable way.

The

Metis were further irritated by the action of several men who attempted

to exploit the lands along the line of the road which was being built.

These men entered into a scheme to buy the land from the Indians for a

nominal price, without recognizing the claims of the Metis. The latter

had always claimed some title to the soil in virtue of their Indian

descent, as well as on the ground of early occupation, and naturally

became indignant when they found them selves ignored by these early

land-grabbers. Believing that Mr. Snow and Mr. Charles Mair, one of his

assistants, were implicated in the scheme, a number of the French

half-breeds went to Oak Point one day in February, 1869, seized Mr. Mair,

and carried him to Fort Garry. They released him only at the earnest

request of Governor Mactavish. Mr. Snow was convicted of having sold

liquor to the Indians in connection with-the land deals and was fined.

There was also some trouble over the purchase of provisions.

The

irregularities in connection with the building of this road finally drew

a remonstrance from Governor Mactavish. In his reply Mr. McDougall said

that the Canadian government had undertaken the road as a measure of

relief for the settlers, !'as the Hudson's Bay Company had

done nothing for the starving people of Red River.'' How unjust this

charge against the company is has been shown in Chapter XXIV. It will be

understood that the incidents connected with the building of this road

and Mr. MeDougall's partial responsibility for them as a minister of the

Dominion government did not raise him in the estimation of the people of

Red River, nor tend to secure him a kindly reception when he came to the

country in another capacity a few months later.

In

the meantime the Dominion government made another blunder. On July 10,

several months before the expected transfer of the Red River Settlement

to the Dominion, Hon. Mr. McDougall directed Colonel J. S. Dennis, D. L.

S., to proceed to the settlement and make preparations for surveying it

into townships and dividing these into sections. Up to this time the

Hudson's Bay Company, in selling land to settlers, had followed the plan

of survey inaugurated by Mr. Peter Fidler in Lord Selkirk's time. Farms

were laid out with narrow frontages along the rivers, and originally

they ran back ninety or one hundred chains, the division lines being at

right angles to the general course of the stream. Subsequently, however,

the length of the farms was extended to two miles. The owner of one of

these narrow farms, or "the inner two miles," was supposed to have the

privilege of cutting hay on a strip of land of the same width as his

farm and extending beyond it to a distance of four miles from the river,

this strip being known as "the outer two miles.'' Thus the farms along

the Red River ran in one direction, while those along the Assiniboine

ran in another; owing to frequent subdivision there was no uniformity in

their width; and the survey of the division lines was by no means exact.

In this way a most unsystematic plan of laying out farms had obtained in

the settlement. Moreover land had been conveyed in a loose manner, and

there was more or less uncertainty about many titles. Any new system of

survey in the districts along the Red and Assiniboine Rivers would

result in endless confusion and possibly in some loss; and Colonel

Dennis warned the government that such a survey as that proposed would

rouse the opposition of the half-breeds, unless their claims were

investigated and settled in advance.

But

the government did not heed the warning, and in October Hon. William

McDougall ordered the survey to proceed. Colonel Dennis attempted to

obey, but he had scarcely put his men in the field before the work was

interrupted. Major Boulton, who was one of the surveying party, tells us

what happened:

"When the surveying party arrived, the first thing done was to send the

horses down to Pointe des Chenes and leave them with those of Mr. Snow,

the overseer of the construction of the road before referred to. Some of

the party were struck with the beauty of the country in that

neighborhood and determined upon taking up land. Then and there they

selected a tract and staked it out for future occupation. This gave rise

to jealousy on the part of the half-breeds in the neighborhood, who

watched their proceedings; and Riel, as it turned out, followed us down

to ascertain what our movements were likely to be. It was not difficult

for him to persuade the half-breeds that this act was hostile to their

interests, and they assembled to intercept us on our way. Riel, who came

with the half-breeds as their spokesman, warned our party that they must

not survey the land or take possession of any of it. The words of his

argument I have forgotten, but the gist of it was to the effect that the

country was theirs, and that we had no right to it and must not survey

it. We informed him that we were only employees of the Dominion

Government and had no control over our movements. There was no show of

violence or hostility in this demonstration, and it did not strike us as

being of importance at the time: It was, however, the first scene in the

drama that was about to be enacted; and 1 have no doubt it gave the idea

to the half-breeds of acting in a similar manner, which resulted in what

is known as the 'stake claims.' "

Colonel Dennis withdrew this party of men and returned to Fort Garry. He

then secured ponies and Red River carts for transport, went to Pembina,

and, following the international boundary west for about ten miles,

began the survey of a line straight north, now called the first

principal meridian, upon which all future surveys were to he based. This

work was not interrupted by the half-breeds and was stopped only by the

sudden coming of winter.

Another detachment of Colonel Dennis' surveyors, in charge of Major

Webb, was less fortunate. It seems to have encroached upon some of the

farms laid out on the old system. Father Morice has given this account

of the affair:

"After private consultations and confidential suggestions exchanged with

the leading Metis of St. Vital, where Riel was established, and St.

Norbert, an important parish adjoining, some secret meetings were held,

the situation was viewed from all points, and the determination was

taken to stop the undue interference of the Canadian English in the

affairs of the country by putting an end to the operations of the

surveyors. In consequence, on the 11th of October, as these were running

their lines across the property of a man named Andre Nault, Riel

presented himself at the head of sixteen unarmed Metis and intimated to

Mr. "Webb, the chief of the Canadian employees, not only that he must

cease His survey but also that he must definitely leave the district.

Then as the English gentlemen turned a deaf ear, Riel and his following

prevented them from continuing their work by riding upon their chains."

Colonel Dennis was annoyed at these interruptions of his work and asked

the local authorities to protect his men from further disturbance; but

they were powerless to take any effective measures to that end. Dr.

Cowan, the officer in charge of the Hudson's Bay Company's post at Fort

Garry, tried to induce Riel's followers to cease their opposition to the

surveys, but he was not successful. Riel was summoned before two

justices of the peace, who remonstrated with him; but his reply was,

"The Canadian government has no right to make surveys in the territory

without the express permission of the. people." When appealed to,

Governor Mactavish called a meeting of the council of Assiniboia, but

that body could do nothing in the existing circumstances.

The

facts, which are usually given as the causes of the Red River rebellion,

have been outlined above, and the disturbances, which formed its

prelude, have been noted briefly; but the real causes of the rebellion

lie much deeper and must be sought in the convictions and feelings of

the people themselves. Allusions to these convictions have already been

made, but the matter will bear more detailed consideration. The

construction of the Dawson road, the new system of surveys, the attempt

of parties from Canada to exploit the lands of the territory about to be

added to the Dominion must have affected all classes of people m the Red

River Settlement; why then were the Metis the only class whose

dissatisfaction found expression in open revolt against constituted

authority?

In

1869 the population of the whole colony was a little more than 12,000.

The Metis numbered about 5,000, the English and Scotch half-breeds about

5,000, and the people of British and Canadian birth about 2,000. There

were aJso a few Americans m the settlement. The Canadian element was

favorable to the acquisition of the country by Canada, and its attitude

had been voiced to some extent by Dr. Schultz and his organ, the

Nor'-Wester. Most of the British-born

residents were favorable to the termination of the rule of the Hudson's

Bay Company and the establishment of some form of self-government in

harmony with British institutions, and probably most of the

English-speaking half-breeds held similar opinions. None of these

people, however, had had

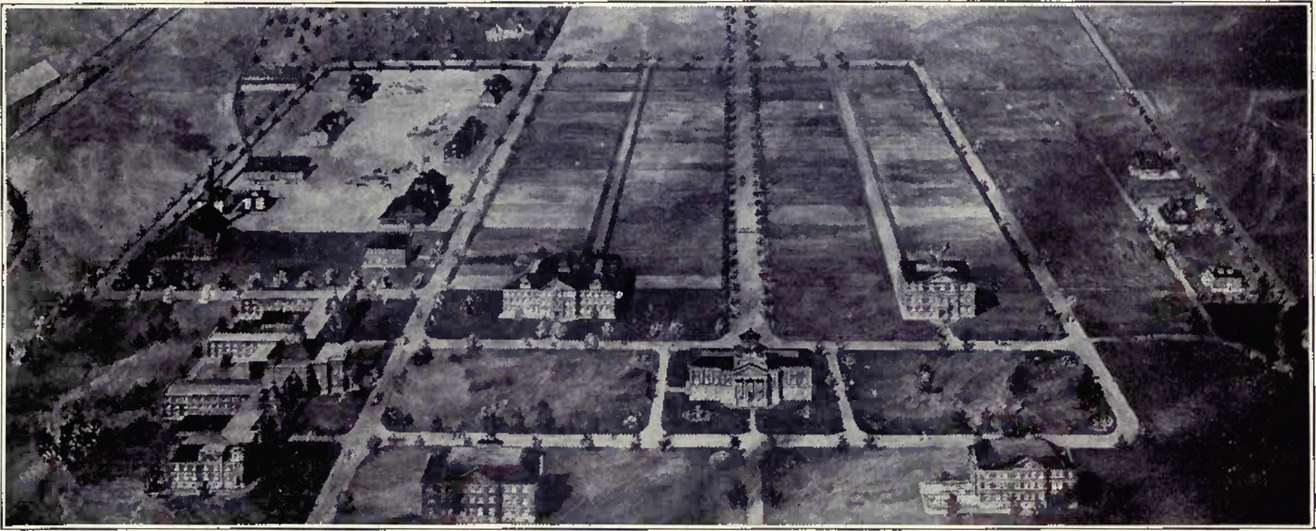

BIRD'S-EYE VIEW OP THE AGRICULTURAL COLLEGE AND

FARM, ST. VITAL

any

voice in arranging the terms by which the country they inhabited was

transferred to Canada. That had been done by representatives of the

Dominion, of the British government, and of the Hudson's Bay Company;

and perhaps this may partly account for the apparent apathy of the

English-speaking settlers in the troubles which followed the transfer.

Their history seems to show, too, that they were lacking in initiative

ability; and their would-be leaders did not command their confidence.

The few American people in the settlement seem to have hoped for the

ultimate annexation of the, country to the United States, and they may

have expected that result to follow, if the troubles between the

settlers and the Dominion government reached an acute stage. They

probably misinterpreted and exaggerated the significance of the petition

of 1846, signed by nearly six hundred people in the colony, asking for

annexation to the United States. The statement that a large sum of money

had been deposited in St. Paul about this time to finance a movement for

the annexation of the Red River Settlement to the United States lacks

proof.

But

the attitude of the Metis was different in some respects from that of

the other classes in the community. Behind their suspicion in regard to

the motives and methods of the Dominion government, behind their old

distrust of the Hudson's Bay Company, lay the feeling of ownership and

nationality. This feeling showed itself in the enmity of the Metis to

the Hudson's Bay Company during the long contest with the Nor'-Westers;

it led them to regard the Selkirk settlers as intruders; and it

responded all too readily to the appeals of Duncan Cameron and Alexander

McDonell in years 1815 and 1816. The "New Nation'' was more than a mere

catch-word among these people. It was the expression of a general

sentiment among them at that time—something akin to real national

feeling and they had never lost it entirely. It is significant that the

newspaper, which became the organ of the Metis during the rebellion, was

called the New

Nation. The Metis maintained that they had

occupied the country before the whites came, even before the Hudson's

Bay Company had established any posts in it, and claimed the rights of

original possessors. It is true that they had never established any form

of government in the country, although they had shown some capacity for

a simple form of government in the organization of their large hunting

parties and a remarkable willingness to conform to its regulations. It

was this feeling of being the original possessors of the country, this

incipient national sentiment, which often made the Metis restless under

the laws adopted by the Hudson's Bay Company. Possibly some recognition

of the rights which they claimed was contemplated in the agreement for

the transfer of the country to the Dominion, although the Hudson's Bay

Company had denied them previously; and the Dominion government

certainly recognized them to some extent later. But these rights had not

been recognized at the time fixed for the transfer, nor had any

investigation of their validity been promised; and so the Metis

naturally suspected that their rights had been sacrificed.

It

is possible that the Metis were also actuated by another feeling—the

natural resentment of a race which finds itself unable, to adapt itself

to changes consequent upon the progress of the country in which it

lives. It sees itself gradually supplanted by another race and

recognizes that its influence must be subordinated to that of a more

progressive people. The recognition of the inevitableness of such a fate

breeds a dull, hopeless anger which has shown itself in scores of futile

outbreaks among aboriginal or semi-aboriginal races against the people

who have dispossessed them. In America, India, South Africa, and

elsewhere the fact has been illustrated again and again.

The

lona-smoldering resentment of the Metis might

never have found expression in open revolt against the existing

government, had they lacked a leader. But a leader, waiting his

opportunity, was present in the person of young Louis Riel. He was the

eldest son of Louis Riel,-'"the miller of the Sein*," who had led the

Metis in their successful resistance to the Hudson's Bay Company in the

Sayer affair in 1846. His mother was a daughter of Jean Baptiste

Laimoniere and his wife, Marie Anne Gabourv, whose romantic story has

been sketched in a previous chapter. On his mother's side he was pure

French, but from his father he inherited a very slight strain of Indian

blood. The younger Louis Riel was born in St. Boniface on October 22,

1844. He grew up a clever lad, and Archbishop Taehe, who had an eye for

promising boys, arranged to have him attend college in Montreal. He was

fourteen years of age when he entered the college, and he seems to have

studied there for five years. The death of his father in 1864 made it

necessary for the young man to return home. It has been stated that he

subsequently lived in the United States for a short time, but during the

two years which preceded the disturbances mentioned in the early part of

this chapter Louis Riel had resided on the paternal farm at St. Vital.

Louis Riel was twenty-five years of age—an age at which youth is quite

confident that the world is ready to accept its ideals. He was better

educated than the majority of his people, full of enthusiasm, and

possessed of a fiery eloquence which was very effective among the

excitable Metis. He inherited some of his father's ability as a leader,

and much of his father's antipathy to the existing government. Strongly

imbued with the Metis' sentiment of nationality and a belief in their

rights, he naturally became its clearest exponent. When a youth, he had

been asked what he intended to do when his studies were completed. "I

will go to Red River," he replied, and follow in my father's footsteps.

He was a benefactor of our people, and I shall seek to be their

benefactor too." Such sentiments, ideals, and ability, combined with

some personal ambition, made Louis Riel the leader of the Metis in their

opposition to the methods adopted in the transfer of the Red River

colony to Canada. |