|

The

Hudson's Bay Company was organized as a trading corporation, not as a

governing body; and while its charter gave it the power to govern its

great territory, this function was somewhat incidental and secondary to

its primary purpose, which was strictly commercial. The primitive form

of government which it established, although sufficient for the Red

River Settlement in the early stages of its history, was quite sure to

be outgrown as the colony developed. For twenty-three years Assiniboia

was under the autocratic rule of its governor; and while his rule was

wise and just for the most part, the speech of Sir George Simpson at the

tirst meeting of the new Council of Assiniboia in 1835 shows us that the

needs of the community could no longer be met by a form of government in

which all the functions of legislation and administration were vested in

one man. The changes made in that year were intended to give the

settlers some part in the management of public affairs; but the measure

of self-government introduced was more apparent than real, inasmuch as

the members of the council, who were supposed to represent the people,

were not selected by them, but were appointed by the governor. Men who

had known the very full measure of self-government which Great Britain

afforded to her citizens could hardly be content with a government in

which they had little or no voice. All classes of the community seem to

have been dissatisfied with some features of the company's rule; and

certain classes had special grievances.

Either because the people had lived in the country so long almost

without laws and courts, or because the new laws were too drastic and

the decisions of the courts established by the new council were too

severe, these courts did not always meet with popular approval. The

first criminal case to be tried in them came up on April 28, 1836. A man

named Louis St. Denis was convicted of theft and sentenced to be

flogged; but the punishment roused so much indignation among the people

that they would have rescued the prisoner, had he not been guarded by a

strong force of constables; and the German ex-soldier who administered

the flogging narrowly escaped very rough treatment at the hands of the

angry crowd.

In

1838 the British government renewed the charter of the Hudson's Bay

Company for twenty-one years, and it seems more than probable that the

improved methods of maintaining law and order in its colony which the

company had adopted made the government more ready to grant this

extension. In the same year the company took what it considered another

step in advance. Up to that date the men entrusted with the

administration of laws in the Red River Settlement had had no special

knowledge of law; hut in 1838 the Hudson's Bay (Company sent Mr. Adam

Thom, a lawyer who had been practicing in

Montreal, to act as recorder for the colony

at Red River Although Mr. Thom had been living in .Montreal for some

time, he was a native oi Scotland and had received his education and

training in that country. He was dogmatic and prone to make long

dissertations on the law as he understood it-facts which did not commend

him to the practical British-born colonists and he did not speak French

- a serious disability in the eyes of more than half the people in the

settlement. He had been appointed by the company at a large salary, and

so public confidence in his impartiality was not perfect, especially in

cases in which the company was one of the parties to the suit. To the

colonists Mr. Thom

sometimes appeared to act both as lawyer and judge, and this did not

meet with their approval.

The

charter of the Hudson's Bay Company appeared to give it the exclusive

right to trade in Rupert's Land; but it does not seem to have, attempted

to enforce its monopoly except in the matter of the fur trade. Indeed it

seems to have tacitly encouraged independent traders, who were doing

business in a small way, by bringing out consignments of their goods

from England and by sometimes carrying their few exports in its ships. A

number of the Metis had established a small but increasing trade between

the Red River Settlement and towns of Minnesota. It was almost

inevitable that the independent traders would occasionally barter goods

for furs; and to check the growth of this illicit trade, as it was

termed, the company sometimes took measures which seemed harsh and

unreasonable. In 1844 the governor of Assiniboia issued a proclamation

which required all letters sent by importers to their agents in England,

and forwarded by the Hudson's Bay Company's packets, to be sent to Fort

Garry unsealed that they might be inspected by the company's officials

before being dispatched. If importers would sign a declaration that they

were not trading in furs, they were not obliged to comply with this

regulation. The merchants objected strongly when the company's officers

tried to enforce this rule; and although Judge Thom held that the

company was justified in making it, the committee in London thought best

to rescind it. Another rule, made about the same time, required all

settlers, who had goods sent out from England by the company's ships, to

make a declaration that they had not engaged in the fur trade. These

rules must have caused much vexation, for in 1847 no less than 102

people in the colony had imported goods from Great Britain or t'h#

United States, the aggregate value being £11,000.

The

duties levied by the company were regarded as burdensome by the

settlers. On June 10, 1845, the council met at Fort Garry and passed the

following regulation dealing with the matter of imports and duties:

"Resolved—That, once in every year, any British subject, if an actual

resident and not a fur trafficker, may import, whether from London or

from St. Peters (in the United States) stores free of any duty now about

to be imposed, on declaring truly that he has imported them at his own

risk.

"That, once in every year, any British subject, if qualified as before,

may exempt from duty as before, imports of the local value of ten

pounds, on declaring truly that they are intended exclusively to be used

by himself within Red River Settlement, and have been purchased with

certain specified productions or manufactures of the aforesaid

settlement, exported in the same season, or by the latest vessel at his

own risk.

"That, once in every year, any British subject, if qualified as before,

who may have personally accompanied both his exports and his imports, as

defined in the preceding resolution, may exempt from duty, as before,

imports of the local value of £50, on declaring truly that they are

either to be consumed by himself, or to be sold by himself to actual

consumers within the aforesaid settlement, and have been purchased with

certain specified productions or manufactures of the settlement, carried

away by himself in the same season, or by the latest vessel, at his own

risk.

"That all other imports from the United Kingdom for the aforesaid

settlement, shall, before delivery, pay at York Factory a duty of 20 per

cent, on their prime cost; provided, however, that the Governor of the

settlement be hereby authorized to exempt from the same, all such

importers as may, from year to year, be reasonably believed by him to

have neither trafficked in furs themselves since the 8th day of

December, 1844, nor enabled others to do so, by illegally or improperly

supplying them with trading articles of any description.

"That

all other imports, from any part of the United States, shall pay all

duties payable under the provisions of 5 and 6 Vict., cap. 49, the

Imperial Statute for regulating the foreign trade of the British

possessions in North America; provided, however, that the

Governor-in-Chief, or, in his absence;\ the President of the Council,

may so modify the machinery of the said Act of Parliament, as to adapt

the same to the circumstances of the country.

"That, henceforward, no goods snail be delivered at York Factory to any

but persons duly licensed to freight the same; such licenses being given

only in those cases in which no fur trafficker may have any interest,

direct or indirect.

"That any intoxicating drink, if found in a fur trafficker's possession,

beyond the limits of the aforesaid settlement, may be seized and

destroyed by any person on the spot.

"Whereas, the intervention of middlemen is alike injurious to the

Honorable Company and to the people ; be it resolved—

"That, henceforward, furs shall be purchased from none but the actual

hunters of the same."

The

license referred to in the above resolution read as follows: "On behalf

of the Hudson's Bay Company, I hereby license A. B. to trade, and also

ratify his having traded in English goods, within the limit of the Red

River Settlement. This ratification and this license to be null and

void, from the beginning, in the event of his hereafter trafficking in

furs, or generally of his usurping any whatever of all the privileges of

the Hudson's Bay Company/' These regulations respecting the trade in

furs affected the Metis more than they did the other people of the

colony, and the former protested against them at once. The Metis had

always claimed the right to buy and sell furs, and as early as 1835 we

find them demanding the recognition of this right and a reduction of the

duties on articles in which they traded. But the company had never

conceded these rights and privileges, and from time to time its

officials had charged traders with buying furs or having them in their

possession unlawfully. If convicted, the offenders would be fined and

their furs would be confiscated.

Such men were generally poor, and sometimes the sentences imposed on

them seemed very harsh. In 1840 it was alleged that a Canadian named

Regis Lau rent had infringed the company's rights, and his house was

broken open and the furs it contained were seized by the company's

officers. Another Canadian was treated in the same way for a similar

offence, and a third seizure was made or the shores of Lake Manitoba,

the owner of the furs being sent to York Factory as a prisoner and

threatened with deportation to England. A few of the Metis, having been

sufferers in the same way, made common cause with the Canadians, and

after a short time the English-speaking half-breeds joined them in their

opposition to the trade regulations of the Hudson's Bay Company. Oddly

enough, it was a love affair, in which a half-breed suitor named Hallet

was rejected because of his mixed lineage, that turned the sympathy of

the English-speaking half-breeds to the Metis in their struggle for free

trade in furs.

The

publication of the regulations adopted by the council in July, 1845, led

to concerted action on the part of English and French half-breeds; and

on August 29 an address, signed by James Sinclair, Baptiste la Roque,

Thomas Logan, John Dease, Alexis Goulet, and fifteen more of their

leading men, was presented to Mr. Alexander Christie, who had lately

come back to serve a second term in the governor's chair. The address

consisted of fourteen clauses, twelve of which were questions in regard

to the rights of half-breeds to hunt for furs or engage others to hunt

for them: their rights to buy furs, receive them as presents, or sell

them; the right of the Hudson's Bay Company to fix the prices of fur;

and the. extent of the territory over which the restrictions, if any,

prevailed. The last clause asked what peculiar privileges the Hudson's

Bay Company bad over British subjects, natives, and half-breeds resident

in the settlement. The governor's reply was written a week later, and

could not have given the petitioners much satisfaction. He told them

that their first nine queries were based on the assumption that

half-breeds possessed certain rights and privileges over their fellow

citizens who had not been born in the country, assured them that all

British subjects had equal rights in Rupert's Land, showed them that the

restrictions of the fur trade grew out of the laws of the country rather

than out of any restrictive clauses in the titles to the lands which

they had purchased from the Hudson's Bay Company, and referred them to

the company's charter and the enactments of the Council of Rupert's Land

for information regarding the peculiar rights of the company. In

conclusion the governor courteously added, "If, however, any individual

among you, or among your fellow citizens, should at any time feel

himself embarrassed in any honest pursuit, by legal doubts, I shall have

much pleasure in affording him a personal interview."

The

governor's suave reply did little to allay the discontent of the

half-breeds, and it was soon aggravated by the frequent attempts of the

company to enforce its monopoly. At last they decided to appeal to the

imperial author ities. A petition, embodying their complaints against

the government of the Hudson's Bay Company and its restrictions on

trade, was drawn up and signed by five of the leading half-breeds of the

colony and forwarded to Mr. A. K. Isbister, who was in England at the

time, ne presented it to the colonial secretary on February 17, 1847. In

reply Earl Grey, the secretary of state for the colonies, proposed that

a commission should be sent to Rupert's Land to

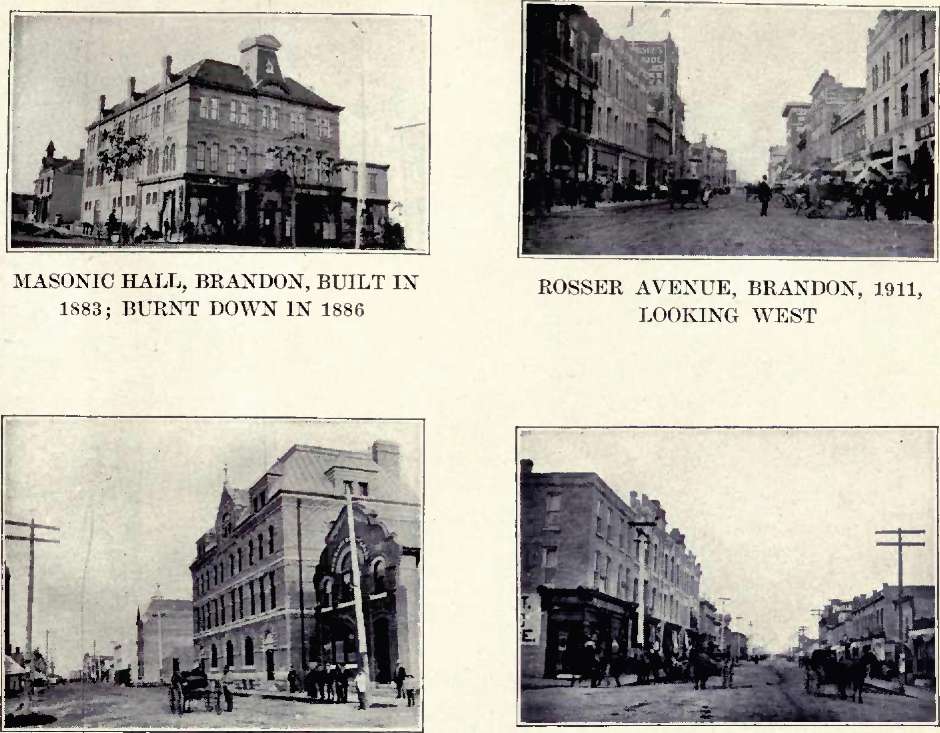

ROSSER A VENUS; BRANDON, .1889, ROSSER AVENUE,

BRANDON,. 1900.

LOOKING EAST FROM ELEV- LOOKING WEST FROM EIGHTH

TENTH STREET STREET

ROSSER AVENUE, BRANDON, 1911, LOOKING EAST FROM

ELEVENTH STRKET

investigate the grievances of the people, but Mr. Ishister objected that

such a commission would be unduly influenced by the company's officials

at Fort Garry. Afterwards the earl asked him for a more detailed

statement of the settler's grievances and Anally suggested that they

might test the matter in the courts. He intimated very plainly, however,

that the validity of the company's charter was not to be. attacked, and

that the petitioners must pay the costs of the judicial inquiry. This

prohibited Mr. Isbister and his friends from taking any action in the

courts, but he continued to agitate for the cancellation of the

company's monopoly and succeeded in interesting a number of members of

parliament in the matter.

The

Hudson's Bay Company seemed inclined to treat the leaders of the

movement against its rule in a vindictive spirit; and James Sinclair,

who had taken an active part in preparing the address to Governor

Christie in 1845 and the petition to the colonial secretary m 1847, was

notified by the governor that the company ships would bring no more

consignments of goods for him to York Factory. This of course was a

great injury to his business. But the harsh measures of the company only

served to rouse the people to more earnest efforts to overthrow its

monopoly, and in 1848 a petition, signed by nine hundred and

seventy-seven half-breeds was sent to the queen, asking for a form of

government more in harmony with the principles of the British

constitution, for freedom of trade, and for the application of some of

the money received by the company from the sale of land to the

improvement of transportation facilities.

The

agitation which Mr. Isbister had started in England and the petitions

sent to the government by the people of the Red River Settlement were

not wholly ineffectual; for when Major Caldwell was sent out as governor

of the colony in June, 1848, he received the following letter of

instructions from Downing Street, dated June 10, 1848:

"Sir— I am directed by Earl Grey to acquaint you that so soon as

circumstances will admit, after your arrival at Assiniboine, Her

Majesty's Government will expect to receive from you a full and complete

account of the condition of affairs at the Red River Settlement, and

particularly of the mixed and Indian population living there; charges of

maladministration and harsh conduct towards the natives having been

preferred against the Hudson's Bay-Company, which it is of the utmost

importance, should be either established or disproved. Her Majesty's

Government expect from you, as an officer holding the Queen's

commission, a candid and detailed report of the state in which you find

the settlement you have been selected to preside over.

"I

would particularly- direct your attention to the allegations which have

been made of an insufficient and partial administration of justice; of

the embarrassments occasioned by want of a circulating medium, except

promissory notes payable in London; the insufficient supply of goods for

ordinary consumption, by the company; and the hardships said to follow

from an interference, which is reported to be exercised in preventing

half-breed inhabitants from dealing in furs with each other, on the

ground that the privileges of the native Indians of the country do not

extend to them. These are only mentioned as instances, and your own

judgment is relied on for enquiry into other points.

I

have, etc.,

(Signed) B. Hawes."

Major Caldwell's training and temperament did not qualify him for the

task of making a thorough investigation into the troubles of the Red

river colony and his position prevented him from making an impartial

inquiry. His investigations were most perfunctory and superficial,

little evidence being recorded which was adverse to the company; and the

general tenor of his lightly-considered report was that the people had

little cause for their complaints against the company.

Events soon contradicted Major Caldwell's report. Early in 1849 the

officers of the Hudson's Bay Company arrested a man named William Sayer

for trading in furs near Lake Manitoba. He was put in prison, but was

soon released on bail. Three other half-breed traders, McGillis, Laronde,

and Goulet, were arrested about the same time and for a similar offence;

but they were released on giving bail to appear when the case against

them was called in court. The Metis determined to make the trial of

these four men a test case and organized for that purpose. The leading

spirit in this movement against the company's monopoly was Louis Riel,

the miller of St. Boniface whose son Louis was prominent in Red River

troubles twenty years later. The elder Riel was assisted by a committee

composed of Benjamin Lajimoniere, d'lTrbain Delorme, Pascal Breland, and

Francois Bruneau.

The

trial was fixed for May 17th, which happened to be Ascension Day, a holy

day for Roman Catholics. However morning mass was celebrated in the

cathedral of St, Boniface at eight o'clock, an hour earlier than usual,

and many people attended, most of them partaking of the holy communion.

After the service was over the men gathered in the churchyard, and Riel.

mounting the steps of the church, made an impassioned address to them,

pointing out the injustice of the restrictions surrounding the trade in

furs, urging united action against the company, and advising implicit

obedience to the orders of their leaders. Then about three hundred of

them, mostly armed, took boats and canoes and crossed the Red River to

Point Douglas. They marched in good order up to Fort Garry, which was

reached shortly before the court opened at. eleven o 'clock. Some, of

their leaders went to the sheriff and told him quite frankly what they

meant to do, but he seems to have contented himself with warning them

against committing any acts of violence.

At

eleven o'clock Major Caldwell, Judge Thom, the other magistrates, and

the officials entered the court-house, the court was opened, and the

case of the Hudson's Bay Company vs. Sayer was called. But the defendant

was detained outside by his friends and could not appear to answer the

charge against him, and so the court went on with other business for two

hours. At one o'clock the case against Sayer was called again, and again

he was not permitted to appear. Then the magistrates sent word to the

half-breeds that they might send a deputation to watch the case on

behalf of Sayer, and the offer was promptly accepted, a committee of

twelve being chosen. This committee under the leadership of Riel then

accompanied Sayer into the court-room, while twenty more of his friends

took up a position just outside the door, and fifty others acted as a

guard at the court-yard gate. A man named Sinclair had been chosen to

conduct the defence of Sayer, but Riel seems to have made one or more

addresses to the court, saying that the arrest of Sayer was unjust and

that the whole population demanded his acquittal. Finally the fiery

miller told the judges that he would give

them an hour in which to make a decision and that his friends outside

would see that justice was done, if the court failed to do so.

When quiet had been restored, a jury was chosen; but when the charge

against Sayer was read, he promptly pleaded guilty, and even urged his

son to tell all the facts which proved the purchase of furs from an

Indian. The jury could do nothing but bring in a verdict of guilty, but

before sentence was pronounced Sayer's advocate proved that his client

had obtained permission to deal in fur from an official of the Hudson's

Bay Company, and the magistrates discharged Sayer without pronouncing

any sentence. The cases against Goulet, Laronde, and McGillis were

dropped; and the four men left the court-room, believing that they had

been honorably acquitted and that the trade in fur would be unrestricted

thereafter. At the door some one shouted, "Le commerce est libre" The

crowd took up the cry, and amid cheers and the firing of guns the Metis

returned to St. Boniface.

The

result of this trial showed the officials of the Hudson's Bay Company

that the people would no longer submit to its monopoly of the fur trade.

The courts, even if they gave decisions in favor of the claims of the

company, had no means of enforcing them against adverse popular opinion.

From that time forward, although the company did not formally renounce

any of its special privileges, trade was practically free.

The

trial had another result. Judge Thom realized that his usefulness as

judge had ceased, and resigned his position as recorder soon after the

trial. He acted as clerk of the court until he left the country to

return to Scotland in 1851; and Major Caldwell seems to have acted as

recorder until Judge F. G. Johnson came from Montreal in 1854 to fill

the position. |