|

Because of Manitoba's geographical position railway communication with

the rest of the world was absolutely necessary to the growth and

prosperity of the province. Until it was obtained all the goods imported

by her people would be very expensive, and it would be almost impossible

to find outside markets for her agricultural products; and these two

facts would greatly retard the settlement of the country. Thus there

were good reasons for the demand for uninterrupted steam communication

between Lake Superior and Fort Garry and the demand for railway

communication between Fort Garry and the rail roads of the United

States, which were given a prominent place in the Bill of Rights

submitted to the Dominion government as a statement of the terms on

which Manitoba would unite with Canada. In passing the Manitoba Act the

Dominion tacitly pledged itself to provide these two lines of

communication between Manitoba and the rest of the world as soon as

possible; and when British Columbia came into Confederation a year

later, the Dominion was formally committed to the construction of a line

of railway, which would connect that province, as well as the North-West

Territories and Manitoba, with eastern Canada.

From the first the people of Manitoba showed a disposition to help

themselves by constructing local lines. Before the first legislature of

the province had meteor even been elected, the newspapers of Winnipeg

contained the following notice:

V

4"-Notice is hereby given that an application will be made,

at the first meeting of the Legislature of Manitoba, for an act to

incorporate a joint stock company for the construction of a railway from

some point on Lake Manitoba, passing through the Town of Winnipeg, and

to connect with the nearest of the Minnesota railways.

Duncan Stxclatr.

E.

L. Barber.

Fort Garry, November 18, 1870." The charter was not granted, but the

application for it shows that the people were alive to the importance of

railways in the new province.

The

Dominion government took prompt steps to carry out the pledges made to

Manitoba and British Columbia. In 1871 it authorized Mr. Sandford

Fleming, who was probably Canada's greatest engineer, to make a thorough

survey of the country north of the Great Lakes in order to locate a

route for the transcontinental railway which it was pledged to build.

The survey was continued across the prairies and through the mountain

ranges which shut

off

British Columbia from the rest of the Dominion. This survey was a work

of great magnitude, requiring much time and the expenditure ol large

sums of money In 1872 the Dominion parliament passed an act to provide

tor the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway. It was to he

commenced not later than July, 1873, and was to be completed in ten

years. Two companies were formed to' carry on the work, but the contract

was not given to either of them When it was found impossible to

amalgamate them, a third company was formed, with Sir Hugh Allan at its

head; its charter was ratified by parliament in March, 1873, and the

contract for the construction of the great national work was awarded to

it.

The

hopes which the people of the west built on this great railway scheme

were not to be realized for several years. There were delays of various

kinds. Before the end of 1873 the--"Pacific Scandal" had developed, and

Sir John Macdonald's ministry had been forced to resign; and in the

interval plans for the great railroad were neglected. When the Mackenzie

government found itself in power early in 1874, it made material

modifications in the railway policy of the Dominion. For the time being

the construction of a road north of the Great Lakes was to be held in

abeyance, and lake steamers were to furnish the first link in

communication between eastern and western Canada. Between Thunder Bay

and the prairies the navigable lakes were to be utilized for steam

communication, and these were to be connected by short lines of railway.

The prairie section of the road was to cross the Red River at Selkirk,

cross Lake Manitoba at the Narrows, and then follow a fairly direct line

to the Yellowhead Pass. The years have proved that a part of Mr.

Mackenzie's railway policy was unwise and a part wise. It was soon found

impracticable to utilize the water stretches between the head of Lake

Superior and the prairie, and the plan was abandoned. The line

ultimately crossed the Red River at Winnipeg instead of Selkirk; and

while its prairie section was diverted far south of the route chosen by

Mr. Mackenzie, the existence of two transcontinental lines on what is

practically his route shows how accurate were his surveyors' estimates

of the great agricultural and mineral resources of the country which

would have been served by the railway he proposed to build. At the time,

however, the people of Manitoba were utterly opposed to the location of

Mr. Mackenzie's road. It avoided the principal town of the province, and

it passed so far north of the settled portions of the country that its

construction would be of little benefit to the people.

The

lack of railway communication with Minnesota was offset to some extent

by the steamers plying on the Red River. During the summer of 1872 three

of these vessels were running regularly .between Winnipeg and points

south of the international boundary. In 1875 several business men in

Winnipeg and Minneapolis established another line of boats on the river,

making a little fleet of five vessels altogether; and a year later there

were seven which made regular trips between Winnipeg and points in the

United States.

The

fact that Minnesota and Dakota had railways, while Manitoba had none,

naturally diverted immigration to those states rather than to the provv

ince lying north of them. It often happened that settlers, who left

eastern Canada to come to Manitoba by way of Chicago and St. Paul, were

persuaded to take up land before their original destination was reached.

For a time it

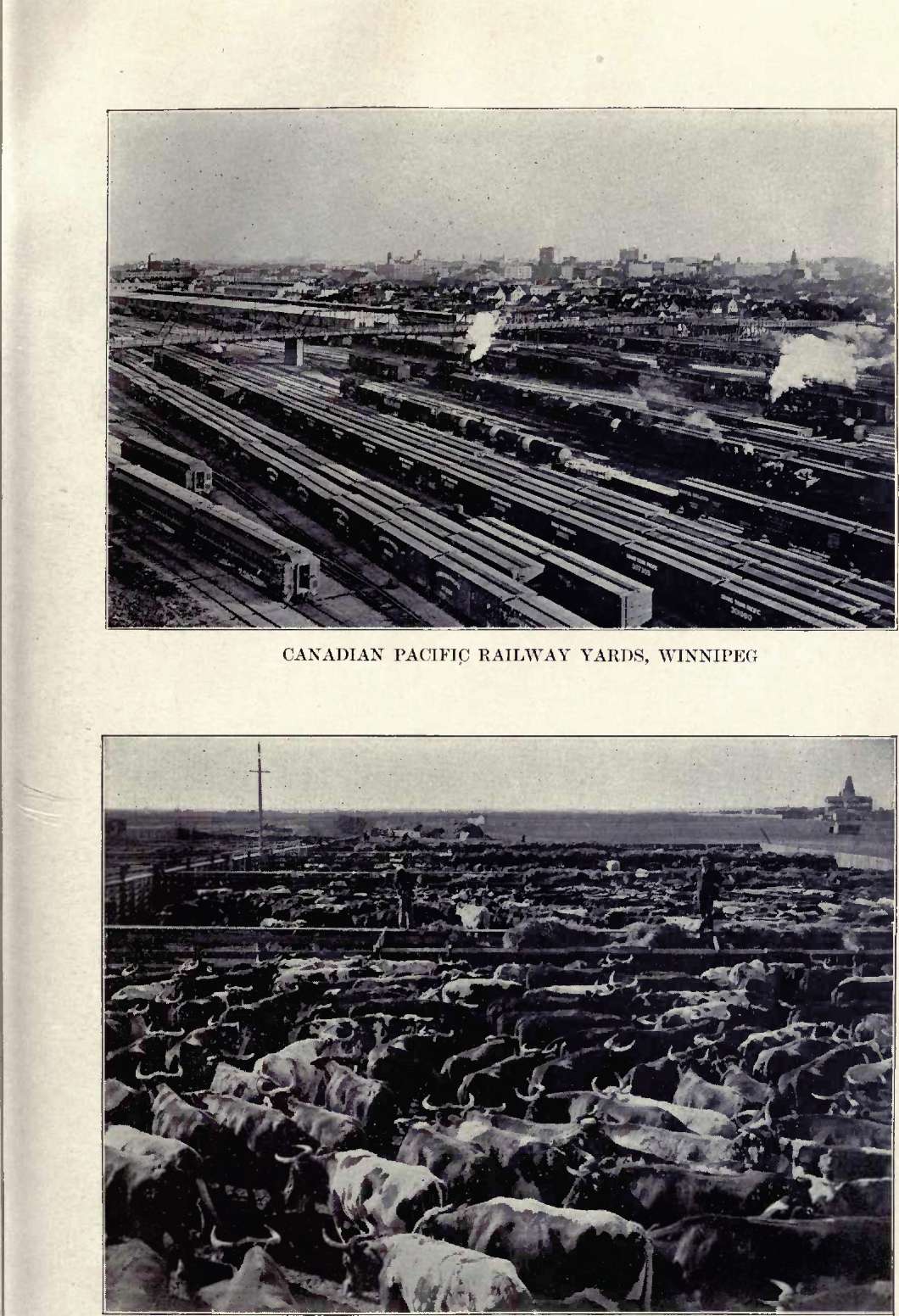

View

of stock yards

was

hoped that this loss to the province might be checked by improving the

Dawson Road and offering immigrants special inducements to travel by it.

When Hon. Mr. Clarke and his fellow delegates presented a memorandum of

Manitoba's demands to the Ottawa government in 1873, its fifth clause

was: ''To have free carriage for immigrants over the Dawson Road from

the port of Collingwood to Fort Garry, and the extension of the said

road to the western boundary of the Province adjoining the North-West

Territories, and the maintenance of the same." The Mackenzie government

made an attempt to comply with this request. In 1874 it made a contract

with Carpenter & Co. to improve the road from Thunder Bay to Winnipeg,

to establish a line of steamers and stages along the route, and to

provide hotel accommodation for travelers. In return for generous

subsidies the company was to convey passengers and freight from Thunder

Bay to Winnipeg at very low rates. But the plan proved unsatisfactory in

every way, and after being tried for two seasons, it was abandoned. By

the end of 1875 the Dawson Road had cost Canada a little more than

$1,294,000.

About 1874 the Dominion government decided on the construction of a

railway from Winnipeg to Pembina to be connected there with the line

which the St. Paul & Pacific Company was building north. The contract

was let to Mr. Joseph Whitehead, and the first sod of Manitoba's first

railroad was turned in September, 1874; but it was a long time before

the people saw the completion of the line. The line was located rather

with the purpose of making convenient connection with the main line of

the Canadian Pacific Railway when the latter was built than with the

purpose of meeting existing needs of the settlers, and there was no

provision for a bridge whereby the line might be brought into Winnipeg.

The importance of changing the location of this Pembina branch was

mentioned in the speech from the throne delivered by Lieutenant Governor

Morris at the opening of the provincial legislature in the early part of

1875, and soon after a delegation went to Ottawa, hoping to secjire

changes in the line which would make it more useful to the people. The

delegation reported that the Ottawa government was unwilling to change

the location of the road, and Mayor Kennedy, who had hoped to secure a

bridge across the Red River so that the line might be extended into

Winnipeg, had to report that there was little likelihood of the railway

being built west of the river for some time. Work on the Pembina branch

went forward slowly.

In

June, 1876, the Dominion government gave notice that it would shortly

ask tenders for the construction of sections of the main line of the

Canadian Pacific Railway between Port Arthur and the Pacific Ocean; but

tenders did not' come in, and in the next year the government itself

undertook the construction of a part of the road west of Thunder Bay. By

the end of 1878 it had 104 miles in such condition that construction

trains were working on it, and other parts of the road had been

ballasted. In the same year the government, convinced of the uselessness

of the Dawson Road, entered into an agreement with the St. Paul &

Pacific Railway Company for a continuous service between St. Paul and

Winnipeg. The government agreed to complete the Pembina Branch as soon

as possible and lease it to the American company for ten years. In May,

1878, a contract for the completion of the line was made with Kavanagh &

Co. The work was to be completed by the end of 1879, but it was done

before the end of 1878, and the first railway train to run on Manitoban

soil, a construction train of the St. Paul & Pacific Railway, steamed

into Emerson on November 11. On December % 1878, the first regular tram

over the Pembina Branch reached St, Boniface. Hoping to make some money

out of the line in the remaining time allowed for its completion,

Kavanagli & Co borrowed a few engines and cars from the St. Paul &

Pacific Company, and attempted to maintain a service on the new road;

but the attempt ended.

The

Mackenzie government went out of office in October, 1878, and with the

return of the Macdonald government came another reversal of the railway

company of the Dominion. The plan of utilizing the water stretches west

of Port Arthur was abandoned, and the main line of the railway was

deflected to its^present position across the prairies. Although this was

probably done to meet the wishes of the imperial government, the change

was welcomed by the settlers of Manitoba as one which would make the

road of greater benefit to them. To secure an efficient service on the

Pembina Branch the government gave Upper & Co. a contract to equip and

operate the road between Selkirk and Pembina until the main line from

Lake Superior could be completed. As soon as the company had equipped

the line, it was to carry out the agreement of the government with the

St. Paul & Pacific Company by interchanging traffic at the international

boundary. In the meantime the American company would run its trains into

St. Boniface over the Pembina Branch; and so in 1879 railway

communication between Manitoba and the rest of the world was an

accomplished fact.

The

people of Winnipeg renewed their efforts to have the main line of the

national railway cross the Red River at Winnipeg instead of Selkirk, but

the government turned a deaf ear to their prayers. When the

South-Western Colonization Railway Company secured a Dominion charter

for building a railway and a bridge across the Red River, it arranged

with the city of Winnipeg to provide $200,000 for the construction of

the bridge. Recognizing the determination of the citizens in the matter,

the Dominion then consented to build a branch of the Pembina line to

connect Selkirk with Winnipeg, if the city would construct a bridge to

give the line entry to Winnipeg.

The

purpose of the Macdonald government to proceed rapidly with the

construction of the main line of the Canadian Pacific was frustrated by

the unwillingness of capitalists to invest money in the enterprise. Sir

John Macdonald and Dr. Tupper went to England in 1879, hoping to secure

the promise of capital for the work, but they were not successful.

Another visit was made during the following year with better results,

and the government felt justified in making a contract with the Canadian

Pacific Railway Company for the construction of the line. After a long

discussion the contract was ratified by parliament in January, 1881. It

was clause 15 of this contract which caused so much trouble in Manitoba

later. It reads: "For 20 years from the date hereof, no line of railway

shall be authorized by the Dominion Parliament to be constructed south

of the Canadian Pacific Railway, from any point at or near the Canadian

Pacific Railway, except such lines as shall run south-west, or to the

westward of south-west, nor to within fifteen miles of latitude 49. And

in the establishment of any new province in the North-West

Territories, provision shall be made for continuing such prohibition

after such establishment until the expiration of the said period.1'

Although the ablest lawyers in the house warned the government that the

Canadian Pacific Railway Act gave it no power to insert this clause in

the contract and although it seemed a plain violation of provincial

rights as determined by the British North America. Act, the government

stood by the clause and the house endorsed it.

The

construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway had been retarded by so

many circumstances that the people of the west realized that several

years must elapse before Manitoba would have direct communication by

rail with eastern Canada and that the province itself must do something

to provide transportation facilities for her people. When Hon. John

Norquay became premier in 1878, one clause of the policy which he asked

the electors to endorse was as follows: "The lack of railway facilities

being severely felt by the farmers, who have no means of conveying their

surplus products to market, the government will encourage local efforts

in the direction of railway construction by granting power to

municipalities to bonus such enterprises and by every other means in

their power." In this there is a hint of the railway policy adopted soon

after by the Norquay government and endorsed almost unanimously by

members of the legislature and by the electors.

When Messrs. Norquay and Royal went to Ottawa early in 1879 to submit

certain demands of the province, one of them was for the endorsation of

its policy in regard to local lines of railway. To it the Dominion

government made the following reply: "That as respects the railway

policy to be pursued in that Province (Manitoba), it has been decided

that the line of the Canadian Pacific Railway shall pass south of Lake

Manitoba, in accordance with the suggestions of Messrs. Norquay and

Royal. The Government will oppose the granting of a charter, for the

present at least, for any railway in Manitoba other than the one

recommended by them, from Winnipeg south-westerly to Rock Lake. The

Government think it very desirable that all railway legislation should

originate here, and that no charter for a line exclusively within the

Province of Manitoba should be granted by its Legislature, without the

Dominion Government first assent thereto." In this reply the- policy of

the Dominion government towards local railways in Manitoba is plainly

foreshadowed; but unfortunately the members of the legislature

overlooked the menace to provincial autonomy which it contained, and no

voice was raised in protest.

The

awakening came two years later. During the session of 1881 the

provincial legislature passed an act to incorporate the Manitoba

South-Eastern Railway Company, which was to build a line from Winnipeg

southeasterly to a point on the international boundary, where it would

connect with some road in the United States. This act was disallowed by

the Dominion government in January, 1882, and the reason given was that

the construction of such a line would be a breach of the contract which

the government had made with the C. P. Ii. Company. The disallowance of

this charter roused great indignation. It was denounced as a violation

of the undoubted rights of Manitoba, and Mr. Norquay's government was

bitterly assailed for submitting meekly to the insult and injury offered

to the province. The

Free Press which had supported the government

up to that time, denounced Mr Norquay and his ministers as incompetents

and charged them with a betrayal of the province. When the legislature

met in April, Mr. Greenway, leader of the opposition, moved as an

amendment to the reply to the speech from the throne, < That this House

regrets that in a matter of such vital importance to this Province as

the recent disallowance, by the Dominion Government, of the

South-Eastern Railway charter, granted by this legislature at its last

session, that his Honor the Lieutenant-Governor

has not been advised to enter his protest against such interference with

our provincial rights. And that in view of the great lack of railway

facilities now afforded this city and province—so much felt at

present—it is deeply to be regretted that the said act should have been

disallowed. thereby indefinitely postponing the additional railway

facilities so essential to the development of the country.^ The

amendment expressed the general sentiment of the people at the time, but

after a long debate it was voted down. The attempts of Mr. Norquay to

find excuses for the action of the Dominion government was the first of

a series of steps which alienated the sympathy of the people and

ultimately led to the defeat of his government.

Before the session closed the legislature passed the Emerson and

Northwestern Railway Act, the Manitoba Tramway Act, and the General

Railway Act of Manitoba; but on November 4, 1882, all three acts were

disallowed by the Dominion government 011 the ground that they

contravened the contract made with the C-. P. R. Company. This second

and flagrant violation of Manitoba's rights roused the deepest

resentment throughout the province. Indignation meetings were held in

many places to protest against the outrage, and many plans to prevent

its repetition were advocated. Under the circumstances Mr. Norquay

decided to dissolve the legislature and appeal to the people. The

election, held on January 23, 1883, seemed to show that the electors

retained confidence in him, for they returned twenty of his supporters

to the legislature, while only ten opposition members were elected.

In

1883 the Dominion parliament passed an Act to Amend the Consolidated

Railway Act. It declared that a number of railroads, including the

Canadian Pacific Railway, "are works for the general advantage of

Canada, and each and every branch line or railway connecting with or

crossing the said lines of railway, or any of them, is a work for the

advantage of Canada.'!" This was an attempt on the part of the Dominion

government to find more valid ground for the disallowance of Manitoba's

railway charters by taking advantage of a clause in the British North

America Act which says, £'The exclusive legislative authority

of Canada extends to such local works and undertakings as, although

wholly situate within a province, are, before or after their execution,

declared by the Parliament of Canada to be for the general advantage of

Canada. The amending act was denounced in Manitoba as a measure intended

to make, the monopoly of the Canadian Pacific Railway Company more

secure, and it certainly retarded the construction of local lines by

other companies for several years.

Manitoba did not tamely submit to this new invasion of her rights. The

pro\incial legislature met on May 17, 1883, and Premier Norquay took an

early opportunity to reassert liis determination to stand by the right

of the

province to charter railways within the boundaries fixed by the Manitoba

Act of 1870. The opposition would have gone a step further, and the

following resolution was moved by Mr. Jackson, one of its members. This

House most humbly prays that your Honor may be pleased to present to His

Excellency the Governor-General the humble protest of this House against

the disallowance of recent acts of this Legislature regarding railways,,

and to represent to His Excellency that this House cannot but regard the

disallowance of acts wholly within the legislative authority of this

province as an infringement upon the rights and privileges of its

Legislature; and this House begs most humbly to declare its intention of

insisting upon the right of the Legislature to the free exercise of all

the powers and privileges hitherto enjoyed by the Legislatures of the

Provinces with reference to railways, and upon its right to authorize

the construction of railways. between any points within this Province

and to the utmost limits thereof, save in so far as this Legislature

voluntarily accepted certain limitations of its authority within the

territory added to this Province in the year 1881." The resolution was

defeated, but the house subsequently endorsed its spirit by passing an

Act to Encourage the Building of Railways in Manitoba.

The

agitation against the "monopoly clause'" of the contract with the C.

P. R. Company continued in all parts of the

province. The burdens under which the people labored seemed doubly heavy

that year. The utter collapse of "the boom" of 1882 had almost paralyzed

every department of business, and the serious injury to the grain crop

wrought by early frosts had left many farmers almost penniless. Never

since have times been so hard in Manitoba as they were in the winter of

1883-4. Under such conditions it was only natural that organizations

should be formed all over the province for the purpose of securing

relief from some of the disabilities from which the people were

suffering. These organizations had various names, but as their aims were

practically identical, they may all be called Farmers' Unions—the name

which most of them adopted. They became an influential factor in the

fight for provincial rights.

A

convention of delegates, representing Farmers' Unions, opened in

Winnipeg on December 20, 1883, and adopted the following Declaration of

Rights:

"1.

The right of the local government to charter railways anywhere in

Manitoba, free from any interference.

"2.

The absolute control of her public lands (including school land) by the

legislature of the province and compensation for lands sold and used for

federal purposes.

"3.

That the duty on agricultural implements and building materials be

removed, and the customs tariff on articles entering into daily

consumption be greatly modified in the interests of the people of this

province and the North West.

"4.

That it is the duty of the provincial government to make such amendments

to the Municipal Act as shall empower municipal councils to build, or

assist in building, elevators, grain warehouses, and mills, within the

limits of such municipalities.

"5.

That it is the duty of the provincial government to appoint grain

inspectors, whose duties shall be to grade all grain brought into market

at central points.

"6.

That this convention is unanimously of opinion that the Hudson Bay

Railroad should be constructed with the least possible delay."

Delegates were appointed to present the demands of the farmers to the

provincial and Dominion governments. The deputation which waited on the

provincial government yim assured by Mr. Norquay that it would do all

iti its power to secure additional railway

facilities and that it would introduce legislation to allow aid to be

given to grain elevators and warehouses, but he made no reference to the

acquisition of public lands. Messrs. Purvis, Mutehmore, and Martin, the

delegates who went to Ottawa in February,

1884, to lay the grievances of the Farmers'

Union before the Dominion cabinet, received little encouragement there.

They were told plainly that no change could be made in the tariff, that

the Hudson Bay Railway was not a present necessity, and that the

monopoly of the C. P. R. Company would be continued until its main line

was completed. These replies were presented to the delegates of the

Farmers' Unions who reassembled at Winnipeg on March

5, 1884. In their indignation at the refusal

of the Dominion government to grant any relief for their grievances, the

members of the convention passed a resolution deprecating further

efforts to secure settlers for the province unless some redress were

granted. This action alienated the sympathy of many people who had

previously supported the union.

When the delegates of the Fanners' Union were in Ottawa, Mr. Norquay was

there, urging upon the Dominion the oft-repeated claims of Manitoba. As

has been stated before, the federal ministers were not disposed to make

further concessions of much practical value; and when the premier

submitted their replies to the legislature in April, both sides of the

house concurred in a resolution which demanded for Manitoba all the

rights and privileges which had been retained by the older provinces

when they were confederated. The cabinet, ministers and the speaker of

the house were appointed as delegates to make another presentation of

the claims of the province, and their instructions were set forth in the

following resolutions:

"1.

To urge the rights of the Province to the control, management .and sale

of the public lands within its limits, for the public uses thereof, and

of the mines, minerals, wood and timber thereon, or an equivalent

therefor, and to receive from the Dominion Government payment for the

lands already disposed of by them within the province, less the costs of

survey and measurement.

"2.

The management of the lands set apart for education in this Province,

with a view to capitalize the sum realized from sales, and apply the

interest accruing therefrom to supplement the annual grant of the

Legislature in aid of education.

"3.

The adjustment of the capital account of the Province, decennially

according to population—the number to be computed now at

150,000 souls, and to be allowed until it

corresponds to the amount allowed the Province of Ontario on that

account.

"4.

The right of the province to charter lines of railway from any one point

to another within the Province, except so far as the same has been

limited by its Legislature in the Extension Act of 1881.

"5.

That the grant of 80 cents a head be not limited to a population of

400,000 souls, but that the same be allowed the Province until the

maximum on which the said grant is allowed to the Province of Ontario be

reached.

"6.

The granting to the Province extended railway facilities—notably the

energetic prosecution of the Manitoba South-Western, the Souris and

Rocky Mountain, and the Manitoba & North-Western Railways.

"7.

To call the attention of the Government to the prejudicial effect of the

tariff on the Province of Manitoba.

"8.

Extension of boundaries."

The

legislature reassembled in May to hear the answers of the Dominion

government. It declined to give the province its public lands, etc., but

would continue the grant of $45,000 a year in lieu of them; it would

transfer to the province all swamp lands reclaimed by the province, and

it would set apart 150,000 acres of agricultural land for an endowment

of the provincial university. It declined to surrender the management of

the school lands, declined to extend the boundaries, and saw no

sufficient reason to make special con cessions to Manitoba in regard to

the tariff. It offered increases in the provincial subsidies amounting

to $208,000 a year and pointed to the large amounts spent in grants to

the G. P. Railway and for investigating the navigability of Hudson Bay

as evidence of its desire to give the province better transportation

facilities. These concessions were valuable, but they were coupled with

a proviso that they must be accepted as a complete settlement of the

claims urged by the delegates. That proviso was fatal to their

acceptance, and the house unanimously decided not to accept them on that

condition.

January of 1885 found Messrs. Norquay and Murray at Ottawa, renewing

negotiations with the Dominion government. As a result of their visit

the government submitted a more generous offer in final settlement of

the demands of Manitoba. It included an annual grant of $100,000 in lieu

of the public lands, a capital account based on a population of 125,000,

a per capita grant of 80 cents based on a population of 150,000, the

transfer of the swamp lands, and a grant of 150,000 acres of land for

the university. The per capita grant would be subject to readjustment at

frequent intervals. The school lands would be held in trust by the

Dominion government, but would be sold at such times and at such upset

prices as the provincial government might recommend. The railway

monopoly would be maintained until the main line of the Canadian Pacific

was completed north of Lake Superior, although lines across the

international boundary might not be objected to after 1881.

When the assembly met in March, Mr. Norquay moved that the terms offered

by the federal government be accepted. There was a long debate, but the

motion was finally carried by a vote of 17 to 9. While the house was in

session a vigorous agitation against the terms offered by the Dominion

was kept up in the country. Early in March the Reform Association and

the Farmers' Union had held meetings in Winnipeg, and both had adopted

resolutions in opposition to the settlement which Mr. Norquay proposed

to make. The Farmers' Union had telegraphed a protest to the

governor-general, and it subsequently sent a petition and a statement of

the claims of the province to the Queen. Throughout the country there

was a growing conviction that the provincial government had surrendered

the most important rights of the proving—the right to her public lands

and the right to charter local railways—in return for a somewhat paltry

increase in her annual subsidy. Before thi close of the session of the

legislature Mr. Greenway moved a vote of want of confidence in the

government, but prorogation took place before the house voted

for motion. Among the

measures passed during the session were the Railway Vid Act, which

allowed the government to advance 5 per cent, provincial bonds at the i

ate of one dollar per acre on any lands granted to railways and thus aid

companies to secure capital for railway construction, and an Act to Aid

the Construction of the Winnipeg & Hudson Bay Railway.

The

railway situation was the subject of much discussion in the legislature

dicing the session of 1886, and it was made more acrimonious by the fact

that orders in council passed at Ottawa had disallowed the charters

granted to the Emerson & North-Western Railway and the Manitoba Central

Railway. The watchword of the opposition was found in a resolution moved

by Mr. Greenway, "That the Dominion Government be requested to make

arrangements with the Canadian Pacific Railway Company to obtain an

absolute and unconditional surrender of all rights and privileges in the

matter of monopoly, and thus secure to Manitoba, and the future

North-West Provinces, similar powers to those enjoyed by the other

Provinces of Confederation in respect to the chartering of lines of

railway." The government's amendment, which was adopted, was, "That the

Government of Canada be asked to make such arrangement when the main

line of the Canadian Pacific Railway is completed and open for traffic

through its whole length, and that in the meantime companies desiring to

construct railways should avail themselves of the provisions of existing

railway acts, i. e., the Railway Act of Manitoba and an Act to Encourage

the Building of Railways in Manitoba." During the session the Hudson Bay

Railway Act was amended so that more assistance could be given to that

railway by the government, and before the year ended some forty miles of

this road had been graded and laid with rails. An act for a

redistribution of seats in the legislature had been passed during the

session, making the total number of constituencies in the province

thirty-five. A general election in December resulted in the return of

twenty-one members supporting Mr. Norquay, but all candidates had

pledged themselves to oppose disallowance of provincial railway

charters.

When the legislature met in April, 1887, the speech from the throne

indicated the determination of the government to take decisive steps

towards freeing the province from railway monopoly. One was to build a

government road from Winnipeg to West Lynne on the international

boundary, and the other was to appeal to the imperial government against

the' continued disallowance of provincial railway charters by the

Dominion. A bill to incorporate the Winnipeg & Southern Railway Company

was introduced at once, and a few days later Mr. Norquay introduced a

bill to authorize the construction of the Red River Valley Railway. This

was to be a government road, open to any company that wished to take

advantage of it. While the bill was under consideration President

Stephen of the C. P. R. Company wrote to Mr. Norquay, threatening to

with draw his company's shops from Winnipeg, if attempts to divert the

traffic of the west southward to American lines were continued; but this

threat only made the people and the legislature more determined than

ever to free the

province from the monopoly which hound her. The Red River Valley Act was

passed, and the hills incorporating the Manitoba Central Railway and the

Emerson & North-Western Railway were re-enacted. In 1885 the legislature

had passed the Public Works Act, and as more than two years had elapsed

without its disallowance, it could not be disallowed by the Dominion.

The provincial legislature, therefore, passed an amendment to it,

providing that injunction proceedings should not apply as a hindrance to

the progress of government works, and the Red River Yalley Railway was

proclaimed a public work within the meaning of the act of 1885. But the

amending act and all the railway acts passed during the session were

promptly disallowed.

The

tirst sod of the provincial railway was turned by Hon. Mr. Norquay on

July 2, 1887, and a few days later a contract for the construction of

the road was let to Harris & Haney, who agreed to complete it by

September 1st, But the C. P. R. Company was determined to prevent this

invasion of the special privilege so carefully secured for it by the

Dominion government. It constructed a spur track from one of its

branches across the line of the Red River Valley road, and one

injunction after another was issued to restrain the contractors from

continuing the work on the Manitoba government's railway. The

construction of the road went forward, nevertheless, until in September

Sir John Thompson, minister of justice, asked the courts to grant an

injunction against the road on the ground that it was being built across

Dominion lands without the consent of the government. The application

came before Judge Killam, who granted the injunction on the ground that

neither the province nor the contractors had any right to build a

railroad over these lands. This checked the work for a time. But other

causes had combined to slop it. The provincial treasury was empty, and

the efforts of Mr. Norquay and Mr. Lariviere to raise more money had

failed. An empty treasury, the relentless hostility of such a powerful

corporation as the C. P. R. Company, and the adverse influence of its

ally, the Dominion government, deterred capitalists from advancing money

to build the Red River Valley road. Mr. Norquay then tried to dispose of

$300,000 of provincial bonds to finance the road, hoping that local men

would take them up, but in this he was disappointed. However a contract

for the completion of the road was let, the contractor binding himself

to finish it by June 1, 1888, "unless prevented from so doing by legal

or military force."!"-'

In

the midst of his struggles against these adverse circumstances, fate

dealt Mr. Norquay its hardest blow and ended his political career. Some

maintained that his downfall was the result of his own mistakes, others

claimed that it was brought about through treachery on the part of some

of his colleagues or on the part of ministers in the Dominion cabinet.

On November 28 one of the members of the legislature, who had supported

Mr. Norquay up to that time-presented a petition to the

lieutenant-governor, in which he charged the premier and other members

of the government with mal-administration of the affairs of the province

and breach of faith with the legislature, inasmuch as they had

transferred large amounts of government bonds to aid companies to build

the Red River Valley and the Hudson Bay Railways without receiving any

security therefor and had let contracts which had never been authorized

by the legislature. Messrs. Norquay and Lariviere attempted to

straighten out the tangled affairs of the government, but did not

succeed j" and when a caucus of the

members of the legislature, who had previously supported them, was held

on December 22 the two ministers announced that they would band their

resignations tr. the lieutenant-governor.

Dr. D. H, Harrison was asked to form a new cabinet which was composed of

Hon. Dr. Harrison, premier, provincial treasurer and minister of

agriculture; Hon. I). II. Wilson, M.D., minister of public works- Hon.

C. E. Hamilton, attorney-general; and Hon. Joseph Burke, provincial

secretary. The life of this ministry was limited to twenty-four days.

The legislature

met on January 12, 1888, and it was soon apparent that the new cabinet

would not receive the support of a majority of the members large enough

to enable it to carry on the government. On January 10 Dr. Harrison and

his colleagues resigned, and the lieutenant-governor called upon Mr.

Thomas Greenway to form a ministry.

The

new cabinet included Hon. Thomas Greenway, premier and commissioner of

agriculture and immigration; Hon. Joseph Martin, attorney-general and

commissioner of railways; Hon. James A. Smart, commissioner of public

works; Hon. L. M. Jones, provincial treasurer; and Hon. James R. P.

Preiider gast, provincial secretary. Two of the new ministers were

returned by acclamation; the others received good majorities; and a

by-election in North Duffierin. made necessary by the resignation of Dr.

Wilson, resulted in the election of Mr. R. P. Iloblin, a strong

supporter of the new government, The people looked to Mr. Greenway as

the leader most likely to put an end to disallowance; and when the

legislature, which met on March 1, adjourned immediately until April lfi

to allow Messrs. Greenway and Martin an opportunity to go to Ottawa for

a conference with the Macdonald government on the subject of railways,

the two ministers felt that they were backed by united and determined

public, opinion. Even the conservatives of the province supported the

ministers in their demand for provincial rights. The Conservative

Association of Winnipeg sent a resolution to Ottawa, declaring that "the

time has passed when mere personal

or political friendship, or party sentiment, can cover or smother the

real state of public feeling in Manitoba and the North-West in respect

to the power (assumed or otherwise), exercised by the governor-general

in council, of disallowing railway charters granted by the legislature

of this province. We declare that we will not submit to struggle any

longer under the burden that is crushing the country to death; we

therefore demand the discontinuance of disallowance and that this

province be placed in the same position in regard to railways as are all

the other provinces forming the Dominion of Canada." The resolution

concluded by asking all members of the senate and the house of commons

representing western constituencies to vote against disallowance.

Sympathy with the province was growing in all parts of Canada, and many

friends of the Dominion government had warned it that Manitoba should

not be deprived of her rights any longer. In view of the strength of

public opinion, Sir John Macdonald and his colleagues were ready to

capitulate.

The

C. P. R. Company had less reason than ever before to demand a

continuation of its special privilege, for its financial position had

greatly improved. In 1884, when it could raise no more money by the sale

of its stock or its bonds, it had to apply to the Dominion government

for a loan of $22,500,000, giving a mortgage on ail its property as

security and a year later it had to seek

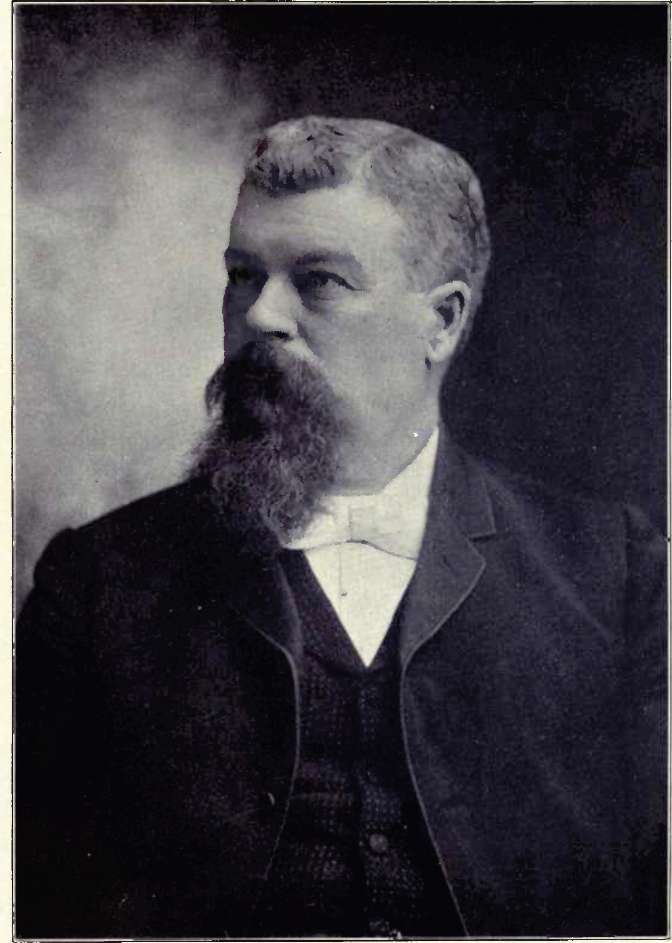

HON. THOMAS GREENWAY

another loan from the government. But in that year it completed its main

line to the Pacific, and had many miles of branch lines in operation; in

the next year its contract with the government was fully completed; and

in 1887 the directors were able to report that its indebtedness to the

government had been met. To secure capital for a further extension of

its lines it then asked the government to guarantee the interest on

$15,000,000 of its five per cent, bonds for fifty years, taking a lien

on 15,000,000 acres of unsold lands as security, and the government

consented, provided the company would forego its monopoly. It held out

for ten years' extension of the monopoly clause, but in the face of

public opinion and some government pressure, it finally agreed to

surrender it. When Mr. Greenway and Mr. Martin met the legislature in

April, they were able to announce that disallowance in Manitoba and the

North "West had ceased. Thenceforward the construction of branch lines

of railway was comparatively easy.

The

new government found the finances of the province in a deplorable

condition; but confidence in its resources was soon re-established, and

$1,500,000 of its bonds were sold on good terms. A part of the money

thus obtained was to be used in the completion of the Red River Valley

Railway as a government road, in accordance with an act of the

legislature passed during the session of 1888. The C. P. R. Company then

offered to lease its Emerson branch to the government, provided the Red

River Valley line were abandoned, threatening to cease building branch

lines in the province, if the government continued the construction. Mr.

Greenway persisted, however, and the people showed their approbation in

the general elections of July 11th by returning thirty-eight government

supporters against five opposition members. In August the new

legislature was summoned to ratify a bargain by which the Northern

Pacific Railway Company acquired the Red River Valley road. The

agreement provided for the construction of a branch line from Morris to

Brandon. About the same time the government's policy towards the Hudson

Bay Railway was modified, and the aid offered was greatly reduced. These

changes in its railway policy cost the government the support of the

Free Press.

The

C. P. R. Company did not cease its efforts to hamper the construction of

competing lines. When an attempt was made to build a line from Winnipeg

to Portage la Prairie across a branch line belonging to the C. P. R.

Company, a force of men employed by the latter and directed by some of

its officials, opposed the crossing. The provincial government ordered

its men to proceed with their work and sent a number of special

constables to protect them. Excitement ran high, and a serious clash at

"Fort Whyte'--seemed imminent; but injunctions restrained the government

work until the matter was settled by the courts.

In

January, 1889, the legislature ratified a new bargain with the Northern

Pacific Company, which saved the province $73,000 a year, and another

modification was made in the terms offered to the Hudson Bay Railway

Company. Mr. Norquay criticized the government severely for its variable

railway policy, and this was one of his last acts in parliament. Before

the next session this man, who in seventeen years of public life had

shown himself one of Manitoba's ablest sons, passed away. He died on

July 5, 1889, at the age of forty-five years. |