|

In

spite of Manitoba's isolation for two centuries after white men first

reached her broad prairies, her history was influenced in many ways by

the policies of the nations of Europe. The early exploration of the

country was accelerated by the old enmity between Britain and France,

and the competition between the Hudson's Bay Company and the French fur

companies was made keener by the desire for national aggrandizement. The

hostility of centuries often showed itself in open war, and on more than

one occasion the war was transferred to the shores of Hudson Bay, where

forts were captured and recaptured by the belligerent powers. Even after

the French had surrendered the whole country to the English, some of the

old hostility survived to add bitterness to the struggle between the

Hudson's Bay Company and the North-West Company and to form an obscure

element in the causes of the Metis rebellion. The Selkirk settlers might

never have come to Manitoba, if Britain had not taken a part in the

Napoleonic wars; and many subsequent migrations of settlers from

European countries have been prompted by a desire to escape adverse

conditions at home as much as by a desire to profit by the fertility of

Manitoba's plains and the riches of her woods and waters. The internal

policies of Russia and Austria, economic conditions in Germany and

Scandinavia, and disasters wrought by the forces of nature in Iceland

have all helped in bringing settlers to Manitoba.

Up

to the time of the transfer of the Red River Settlement to Canada the

increase in its population had been steady but somewhat slow. The Riel

insurrection, which appeared such a disaster in itself, seems to have

given an impetus to immigration by drawing attention to Manitoba and its

resources; and the volunteers in Wolseley's Red River Expedition were

the best immigration agents the province could have had. Many of them

decided to make their homes in the country when their term of service

expired, and their reports about its advantages brought many settlers

from eastern Canada to share in the develop ment and progress of the new

province.

The

movement of settlers from eastern Canada to Manitoba was imped for many

years by lack of transportation facilities. Two routes were open to

them, but both presented serious difficulties. One took them across the

Great Lakes and over the Dawson Route; the other took them through the

United States to the farthest point in Minnesota reached by rail and

then down the Red River in flatboats or steamers. The movement of

settlers from Ontario to Manitoba began in 1871. In April of that year

an advance party of eight left their homes, travelled by rail to St.

Cloud, Minnesota, went thence by wagons to Fort Abercrombie on the Red

River, built a flatboat there, and when the stream was clear of ice,

made their way to Winnipeg. Large numbers of Ontario people followed as

soon as summer came, and by August the hotels of the little town of

Winnipeg could not accommodate half the new arrivals. It became

necessary to tit up a shed in the rear of Bannatyne & Begg's store as an

immigration hall, and there the wives and children were sheltered while

husbands and fathers were selecting their farms. In October Mr. J. A.

N.-Provencher came to Winnipeg as immigration agent, and the information

and advice, which he was able to give, were very helpful to the new

settlers. Through the efforts of Premier Clarke and Consul Taylor, the

government of the United States relaxed some of its customs regulations,

making it easier for settlers to bring their effects through that

country. The movement of people from Ontario continued in 1872, many of

them taking up land west of Portage la Prairie.

A

few years later several thousands of settlers found their way to

southern Manitoba as a result of a change in the policy of the Russian

government towards certain classes of its subjects. In 1786 Catherine

the Great, Empress of Russia, invited members of the religious sect

known as Mennonites to leave their homes in Prussia and settle along the

lower course of the Dnieper River, offering them free transportation,

free lands, freedom of religion, and exemption from military service.

Many accepted the offer, and several hundred families had settled in the

district before the empress died in 17!)6. Fearing a loss of their

privileges, these people induced her successor, Paul I, to confirm them

by a charter, still preserved at Chortitz. The concessions thus secured

encouraged more of the Mennonite brethren to migrate to southern Russia,

and a new settlement was formed along the Molotchna River near the Sea

of Azov, and about 1860 a third settlement was established in the

Crimea. Other German people followed the Mennonites, and by 1870 Germans

formed a large element in the population of southern Russia. Nearly all

these people were farmers, and their industry and thrift had made them

the most prosperous people in the country.

Their success roused the envy of other people living in that part of the

Russian empire and led to a demand for the cancellation of the special

privileges enjoyed by the Mennonites; and about 1870 a treaty was made

between Russia and Germany, by which the latter renounced her

guardianship over the German inhabitants of southern Russia. The Russian

government then required the Mennonites to become full Russian citizens,

allowing those who were unwilling to do so ten years in which to dispose

of their property and find homes elsewhere. The order spread

consternation among the Mennonites. If they remained, they were liable

for service in the army—a thing forbidden by the rules of their

religion—their children would be educated in the Russian schools, and

certain valuable privileges would be withdrawn; and if they went

elsewhere, they could hardly hope to dispose of their property except at

a great loss. Appeals to St. Petersburg failed to move the government,

and while some of the Mennonites decided to conform to the w order of

things, the more conservative among them felt that they must migrate to

some country where they could live in conformity with the tenets of

their religion. They therefore sent delegates to various parts of the

world, looking for a country in which soil and climate were somewhat

similar to those of southern Russia and where military service would not

be compulsory.

As

the Mennonites seemed to be people almost certain to succeed as new

settlers on the prairies of the west, both the United States and Canada

made efforts to secure them. In 1872 a delegate from one of the

Mennonite settlements in Russia visited Manitoba in company with Mr.

Jacob Y. Shantz, a prominent member of one of the Mennonite churches of

Ontario; and a year later, when Hon. 'William Hespeler visited the

Mennonite colonies in Russia as an agent of the Dominion government,

this delegate was able to confirm his accounts of the soil and climate

of Manitoba. Mr. Hespeler's most effective work appears to have been

done in the villages along the Molotchna, where the Mennonite people

were rather more conservative than in other districts. One result of his

visit, was the appointment of a deputation of twelve men, some

representing the Mennonite settlements in Russia and others communities

in West Prussia, to visit America and select localities best suited for

the people who had decided to emigrate. The names of the delegates were

Jacob Buller, Leonard Suderman, William Ewert, Andreas Schrag, Tobias

Unruh, Jacob Peters, Heinrich Wiebe, Cornelius Ruhr. Cornelius Toews,

David Classen, Paul Tschetter, and Lawrence Tschetter; and one of thein,

Mr. Suderman. has written an account of their trip. These men left their

homes early in the spring of 1873 anil journeyed, via Berlin. Hamburg,

and Liverpool, to New York. There they separated, some to inspect one

part of the country, some another. Messrs. Buller, Unruh. and Suderman,

accompanied by Mr. Hespeler, went to Ontario. Mr. Shantz joined them,

and the party then went west to Manitoba by way of Chicago, St. Paul,

and Pargo, being joined at Fargo by the other members of the deputation.

They spent about three weeks in examining different parts of Manitoba

and then went south to examine various districts of the United States.

On

their return to Russia the delegates reported that the district about

half way between Winnipeg and the international boundary was well

adapted for a Mennonite colony, and early in 1874 many people in the

settlements along the Molotchna and the Dnieper sold their property and

applied for passports to America. Alarmed at the number of people who

wished to emigrate, the Russian government offered some concessions in

regard to military service to the Mennonites; but while these offers

checked the exodus, they did not stop it. In some cases whole villages

went away together.

A

large percentage of these people came to Manitoba in large or small

parties. One party, which had made Toronto their rendezvous, numbered

504 persons when it embarked on the train there. The movement continued

all the year, the ships of the Allan line alone bringing 230 families

across the sea. The Dominion government had reserved twenty-five

townships in Manitoba for the Mennonites, eight being or. the east side

of the Red River some twenty-five miles south of Winnipeg, the others

being on the west side of the river and nearer to the international

line. The influx of Mennonite settlers during 1875 was much greater than

that of the previous year, but in 1876 the tide slackened, and by the

end of that year it had practically ceased. In 1874 the Mennonites

coming to Manitoba numbered 1,368, in the next year 4,637 arrived, but

in 1876 1he number fell to 1,141. In August, 1879, the total Mennonite

population of Manitoba was estimated at 7,383.

The

Mennonites of Manitoba settled in villages, containing from five to

thirty families each. Their houses were built close together along both

sides of a wide street, with gable ends facing this street. Most of them

had flower and vegetable gardens attached to the lots on which the

houses stood. The farms were located about the village, and were so laid

out that the owners shared equally in the poor land as well as the good.

A certain amount of land was set apart as a common pasture for the

cattle belonging to the inhabitants. Each village had a school, and in

the smaller villages it also served as a church: but in the larger

villages there was a special building for religious services. Nearly

every village had a blacksmith's shop, and the larger villages had mills

and stores. The Mennonites were to be exempt from military service, they

were given absolute freedom in religious matters, and they were left

practically free to carry out their own system of village government.

Many of the Mennonites who came to Canada were very poor, and it was

necessary to advance them money to enable them to begin farming on the

unbroken prairie. Their co-religionists in Ontario formed a committee,

with Mr. J. Y. Shantz at its head, to raise money to be lent to their

brethren in Manitoba, and they also gave security for a loan of $96,000

made by the Dominion government. It is estimated that the total amount

of money advanced to the new Mennonite settlers in Manitoba was not less

than $175,000, and it speaks well for the thrift and honesty of these

settlers that all those loans were repaid before twenty years had

passed. Some of those who settled on the east side of the Red River did

not secure very good land, and a few became discouraged and moved away;

but practically all of those who remained on their lands prospered, and

some of them grew rich.

While the Mennonites of southern Russia were migrating to countries

where they would be free to live in conformity with the rules of their

religious creed, the inhabitants of the northwestern outpost of European

civilization, Iceland, were seeking other lands because nature continued

to devastate their own. More than eighty per cent, of the people of the

island were raisers of cattle and sheep; but frequent earthquakes and

volcanic eruptions had destroyed so much of the pasturage that it became

more and more difficult for many of the inhabitants to make a living,

and they began to look toward countries where opportunities might be

better.

Emigration from Iceland to America began about 1870; but during the next

two or three years very few people left the island, and most of these

found homes in Wisconsin, although one or two made their way to Ontario.

The letters written by these wanderers to their friends and the

newspapers of their native land roused a great interest there; and when

a meeting of people who had made up their minds to emigrate was held at

Akureyri in July, 1872, the majority decided that they would go to

Ontario. There were 180 people in the party, and while a few went to

Wisconsin, the most of them went to the Muskoka District and took up

farms in the bush country. Another party, numbering 365, left Iceland

during the summer of 1874, It appears that many of these people had paid

their passage money to a Norwegian shipping firm, which failed just

before the party left home. After paying for their passage a second

time, these people; had little money with which to make a start in a new

and strange country. Some of them located in Nova Scotia, but the

majority went to Ontario and were sent to the neighborhood of Kinmount,

where they might obtain employment in building a new line of railway.

The contractors suspended work before spring came, however, and the

Icelanders found themselves in a very difficult position. Rev. John

Taylor, a clergyman living near them, interested himself in these worthy

people and went to Ottawa, hoping to induce the government to adopt a

scheme for settling them in Manitoba. Lord Dufferin. the

governor-general, seems to have approved of the plan, and finally the

government adopted it.

On

May'30, 1875, the Icelanders held a meeting at Kinmount and selected

delegates to go to Manitoba and find, if possible, suitable home for

them. The delegates were Captain S. Jonasson, Mr. Skafti Arason, Mr.

Christian Johnson, and Mr. Einar Jonasson. These men left for the west

on July 2, and on the way they were joined by Mr. S. Christopherson, a

delegate from the Icelanders living in Wisconsin. They went to Moorhead

by rail and thence to Winnipeg by steamer, arriving on July 16. After a

careful examination of the country the delegates decided that a district

on the west side of Lake Winnipeg would suit their countrymen. Many of

them had been cattle-raisers and fishermen at borne, and the country

immediately west of the lake seemed well adapted for cattle-raising,

while the lake itself furnished abundance of fish. The lake and the Red

River afforded water communication with Winnipeg, and the site of the

settlement would not be far from the proposed Canadian Pacific Railway,

which was to cross the river at Selkirk and run northwesterly to the

Narrows of Lake Manitoba. Moreover, the district selected had not been

occupied by settlers of other nationalities.

Three of the delegates went east to make their report, and the others

remained in Manitoba to make preparations for the coming of the new

settlers. Late as it was, 250 of the Icelanders in the vicinity of

Kinmount decided to move to the shore of Lake Winnipeg before winter set

in. They were joined by others on the journey, and when the

International landed the party in Winnipeg on

October 11, it comprised 85 families, numbering 285 souls. Flatboats

were secured in Winnipeg, and having loaded their supplies upon them,

the immigrants embarked and started for their destination on the 17th.

They floated slowly down the Red River, reaching its mouth on the

morning of the 21st, and then the Hudson's Bay Company's steamer, the

Colville, towed them across the lake and

landed them near the site of the present town of Gimli just as the sun

went down. They had been thirty-two days on the journey from Kinmount.

On the wav some of them had occupied themselves in making nets, and

before darkness fell these nets were set in the lake which was to

furnish the people a large part of their living for several years. A

long and severe winter set in almost immediately, yet the Icelanders

managed to build log houses in which they found shelter; and in a short

time the colony became self-supporting. A few of the Icelanders in this

first party remained in Winnipeg, the pioneers of several thousands of

their countrymen now residing in the city and taking a high place in all

departments of its life.

A

second party of Icelanders reached Winnipeg on August 11, 1876. having

come directly from their native land. Mr. John Dyke, an immigration

commissioner of the Canadian government, had aided them in making

sailing arrangements ; and as many of them were poor, the government had

to assist them in making the passage. It also advanced them supplies for

a month after their arrival. Most of the members of this party settled

among their friends beside Lake Winnipeg.

Before the end of 1876 misfortune overtook the Icelandic colony.

Smallpox broke out at Gimli and spread rapidly through the settlement.

At that time Gimli lay in the District of Keewatin and north of the

Manitobau boundary, and the Dominion government had not appointed a

council for the district. As soon as the report of the outbreak of the

epidemic reached Ottawa, a council was appointed, and this council and

the government of Manitoba took concerted measures to check the spread

of the disease. The settlement was quarantined, and a company of

soldiers was sent from Winnipeg to points east and west of the mouth of

the Red River to enforce the quarantine. Dr. Lynch and others

volunteered for service among the afflicted people, and by the end of

the year they seemed to have the epidemic, well under control. It broke

out again, however, and carried off many of the settlers before it was

completely stamped out.

The

smallpox epidemic does not seem to have retarded Icelandic immigration

to any extent. A third party came out in 1878 and settled at Gimli, and

each succeeding year added to the Icelandic population of the province.

By 1885 they had extended their settlement from the shore of Lake

Winnipeg to that of Lake Manitoba, and five years later they reached the

Narrows. The movement in a northwesterly direction continued, and in

another decade there were Icelandic settlements beside Lakes Dauphin and

Winnipegosis and in the valley of the Swan River. All the Icelandic

immigrants, however, did not settle in districts where woodland and

meadow alternate and where lakes and streams are abundant. Many of 1hein

took up land in districts suited for grain-growing and mixed farming. A

large number settled in the municipality of Argyle in 1881 and the

following years, others located in the municipality of Stanley, and

still others near the western boundary of the province. .Many found

occupation in the towns, especially Winnipeg, Selkirk, Brandon, Baldur,

and Glenboro. By the end of the century the total Icelandic population

of Manitoba was estimated at 10,000, and natural increase and continued

immigration have probably doubled it since. Speaking to the Icelanders

during his tour of Manitoba in the summer of 1877, Lord Dufferin said,

"I have pledged my official honor to my Canadian brethren that you will

succeed;'' and they have fully redeemed the governor-general's pledge.

The

act, which embodied the policy of the Mackenzie government in regard to

the Canadian Pacific Railway, was passed by the house of commons in the

spring of 1874. According to it, the main line might be built as a

government work or it might be given to contractors. In the latter case,

the contractors would receive twenty thousand acres of land per mile as

part payment for their work. As a result large areas of public land in

Manitoba were held as railway reserves and were not open to immigrants

seeking farms. This greatly impeded the progress of the country, but in

spite of the protests of the people and their representatives in

parliament the Ottawa government did not modify its policy until 1877.

Then a change in the law opened railway reserves to actual settlers,

although the man who bought these railway lands., as well as the man who

had squatted on- them previous to their reservation, was left in much

uncertainty as to the amount which must ultimately be paid for them.

But

in spite of the uncertainty about the location of the national railroad,

the restrictions in regard to Dominion lands, and the occasional ravages

of grasshoppers, the population of Manitoba grew rapidly. There was a

steady influx

of

settlers from the older provinces of Canada as well as from the

countries of Europe. Many large parties arrived during 1878, the tirst

reaching "Winnipeg by steamer on April 17 In the sixth large party,

which arrived in October, there were 480 families. Individual settlers

and small groups of immigrants continued to come to the country

throughout the summer, and the number of new arrivals in Winnipeg was so

far in excess of the accommodation provided for tliem that it was

necessary to use the barracks at Fort Osborne as an annex to the

immigration hall. The great demand for land induced several business men

of Winnipeg to open real estate offices.

When the conservative party returned to power at Ottawa, the policy of

the Dominion government in regard to lands set apart to aid in the

construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway was changed once more. By

regulations adopted on August 1, 1879, settlers were debarred from

taking homesteads and pre-emptions in the belt of country extending for

five miles on each side of the main line, although they were allowed to

purchase lands in this belt at $6 per acre. In the more distant belts of

the railway reserve, homesteads and pre-emptions might be taken, and the

land might be bought outright at much lower rates than were charged for

it in the inner belt. There was so much opposition to these rules that

they were cancelled in October and replaced by others which permitted

settlers to take homesteads and pre-emptions in all parts of the railway

reserve; but even after this change, the policy of the government was

not conducive to the rapid settlement of the vacant lands of the

province.

The

completion of the railway from St. Vincent to Winnipeg in the autumn of

1878 tended to offset the somewhat illiberal land policy of the

government, and the next year brought a large influx of settlers to

Manitoba. The movement from Ontario was larger than ever before, many of

the best farmers of the counties of Huron, Bruce, Grey, and Wellington

selling their holdings there in order to take up land on the western

prairies. Parties arrived at St. Boniface almost daily, and many of

their members brought considerable capital. Some of these men took up

land in the district east of Winnipeg, others selected farms ai southern

Manitoba, while many went west to locate somewhere near the main line of

the railway. The Hudson's Bay Company placed some of its land in the

market on very favorable terms, and yet the number of homesteads and

preemptions taken during 1879 exceeded that for the two preceding years.

Settlement made rapid progress in the two succeeding years, and we are

told that in 1881 the total area of the occupied lands of the province

was 2,384,337 acres, of which 250,416 acres were cultivated and 230,264

acres were under crop.

In

March, 1882, the Dominion government withdrew all even-numbered sections

of land within one mile on each side of the Canadian Pacific Railway

from pre-emption and homestead entry, and in July all the lands south of

the twenty-four mile belt were withdrawn. It was alleged that this was

done to prevent speculators from securing large quantities of land along

the branch lines which would soon be built; but

111 the following year legislation was

enacted to accomplish this purpose, and then the even-numbered sections

south of the railway belt were once more opened to entry for homesteads

and pre-emptions. As the railway and its branch lines were extended

through the province, the railway company came into possession of great

areas of land, much of which it wished to have settled as soon as

possible; and so the company became an active immigration agent and

helped to increase the tide of immigration setting toward Manitoba.

The

rapid increase in the population of the province, and the consequent

increase in its capital and the amount of business transacted throughout

the country resulted in prosperity unknown before; prosperity led to

speculation; and speculation culminated in "the boom" of 1882. A mania

for buying and sell in sr real estate seized the people. The prices of

lots in the city of Winnipeg were forced up to many times their real

value, the prices of lots in the smaller towns were similarly inflated,

and farms were subdivided into lots where towns could never be expected

to grow. In many eases lots were sold in towns which never existed save

on paper. A similar unwarranted inflation pervaded all departments of

business. It could not last, and after a few months the crash came. Many

men, who dreamed that they had become rich, woke to find themselves

ruined. During 1883 and a few of the succeeding years business in

Manitoba was at low ebb, and it was a long time before the country

recovered from the disastrous effects of "the boom".

About this time the west received from Russia another addition to its

population. The Jews in that country were placed under many

restrictions, not because of their race but on account of their

religion. If a Jew forsook his religion and united with the orthodox

national church, all the privileges of full Russian citizenship were

open to him; but as long as he adhered to the faith of his forefathers,

he was subject to many disabilities. He was obliged to pay taxes, but he

could not own land; he was compelled to serve in the army, but he could

not obtain an officer's commission in it; lie could not hold any

government office; he could not enter any of the professions, except

that of medicine; he could not reside outside of certain restricted

districts. Under such conditions it was difficult for most of the Jews

to live in comfort, impossible for them to live in content.

Anxious as they were to move to some country where they would not be so

heavily handicapped in the race of life, poverty kept most of the

Russian Jews from emigrating. The time came, however, when they received

assistance from other countries. Aided with money from the Mansion House

Fund, to which Baron Hirsch was a generous contributor, and directed by

the London (Eng. J

Board of Guardians, quite a large party of Russian Jews came to western

Canada in 1882. Most of them were mechanics; and while some of them

remained in Winnipeg to enter such callings as were open to men with

such limited capital, many went further west and formed an agricultural

colony in the neighborhood of Wliitewood, Sask. The majority of the

people who came in this first large party, those who located in the city

as well as those who became farmers, met with success; and since 1882 a

steady stream of Jewish people has flowed into the west. The majority of

them have come from Russia, all parts of that country being represented,

although in recent years the disturbances in the southern provinces have

increased the proportion from that part of the empire.

These people receive direction and help from the Jewish Colonization

Society, and this organization lends money to those who prove themselves

worthy of assistance in that way. As far as possible they are sent to

the agricultural colonies, of which there are seven or eight in

Saskatchewan and Alberta; but a number of them remain in the cities and

towns of Manitoba. The Jewish population of Winnipeg received a

considerable addition in 1896 because of the persecution of these people

in Koumania, and the disturbances in Russia which followed the

Russo-Japanese war caused an increased influx from that country. The

Jewish population of Winnipeg alone is estimated at more than 12,000,

and it has many able representatives in business, the professions, and

public life.

It

must not be supposed, however, that all of Manitoba's Jewish settlers

have located in the cities and towns. There is an agricultural

settlement north of Shoal Lake, founded in 1906 and known as Bender

Hamlet, in which the houses form a little village while the farms are

scattered around it. The people in this colony brought with them the

communal system with which they were familiar in Russia. Another colony

was established near Pine Ridge, about eighteen miles northeast of

Winnipeg, in 1910. Most of the people in it are market-gardeners and

dairymen, each man owning his little farm. New Hirsch is another

settlement of Jewish farmers, established in the district east of Lake

Manitoba during 1910.

Hoping to relieve the distress among the Crofters in some parts of the

western highlands of Scotland, Lady Cathcart and other benevolent

persons devised a plan for settling them on farms in southern Manitoba

and other parts of western Canada. The first party was sent out in 1883,

and another followed in 1884. Substantial aid in cash, stock, and

implements was given to them; but the conditions in a newly settled

prairie country were so strange to these people that they made little

progress for a long time. Some of them ultimately attained success, but

many failed utterly.

It

is probable that the success of Scandinavian settlers in Minnesota and

Dakota led some of their friends at home to emigrate to Manitoba. As a

rule the Swedish people have not come to the province in large parties,

nor have they settled in colonies, although there are a few exceptions.

About 1884 quite a large party of Swedes arrived in Winnipeg, and soon

after, acting on the advice of some of their fellow-countrymen, they

formed an agricultural colony about twenty miles north of Minnedosa. A

similar colony was established on Swan River thirty years later; but

most of the Swedish farmers settle in districts inhabited by people of

other nationalities.

The

collapse of the land "boom" of 1882 and the succession of poor crops

which followed seriously retarded immigration to Manitoba for some time,

but in 1886 conditions began to improve. The Dominion government made

another modification in its land regulations during the year, allowing

more freedom in making entries for homesteads, giving more time in which

to commence cultivation and erect a dwelling, and facilitating the issue

of patents. The privilege of taking second homesteads was withdrawn, and

pre-emptions were to be discontinued after 1890. On July 1, 1886, the

completion of the main line of the Canadian Pacific Railway from

Montreal to Vancouver was marked by the arrival of the first

transcontinental train in Winnipeg. The completion of the road north of

the Great Lakes made it much easier for both Canadian and European

settlers to reach the west. The census of 1886 gave Manitoba a

population of 108,640. The area of land occupied was 4,171,224 acres,

751,571 acres being under cultivation.

On

September 15th 1898, two Russian families arrived in Winnipeg and

reported themselves to the immigration commissioner, Mr. W F. McCreary.

They proved to be the scouts of an army of immigrants, the precursors of

a movement without parallel in the history of the Canadian west. They

belonged to the religious sect called Dounhobors, and had come to

Manitoba, seeking suitable districts for colonies of their

co-religionists, whose peculiar tenets had brought them into such

serious and long-continued conflict with the authorities of the Russian

government that they bad decided to migrate to some other country. The

two Russian families were accompanied by Mr. Aylmer Maude and Prince

Ililkoft", and the immigration officers had been instructed to give them

all possible assistance in securing information about Manitoba and the

Territories. They made a thorough examination of the parts of the

country in which considerable areas of land were open for homesteading,

and finally selected two districts in which to establish Doukhobor

settlements. One lay entirely in the present province of Saskatchewan;

the other was in the Thunder Hills district near the upper affluents of

the Assiniboine and Swan Rivers, partly in Saskatchewan and partly in

Manitoba.

In

a few weeks a remarkable migration began. The Doukhobors came by

thousands, apparently without regard to the season of the year, the

possibility of getting on their reserves, or the chance of obtaining

employment or even shelter. The first party, which reached Winnipeg on

January 27, 1899, included 2,076 persons. They were housed in the

immigration hall, an old building which had once been a school, and

other available places. Although there seemed to be no more shelter for

these people, 1,973 arrived in February, 1,036 came in May, and 2,335 in

the early part of July. The first two parties had come via Hamburg, but

the third took ship at the Island of Cyprus and sailed directly to

Canada. The people in it brought tents with them, and the government was

not required to find shelter for them; but for the members of the last

party no place could be found in Winnipeg, and they had to be sheltered

in the old round-house of the Canadian Pacific Railway at East Selkirk.

The total number of Doukhobors who came to Winnipeg during the year was

7,427.

The

Doukhobors were an agricultural people, but as soon as they arrived in

Manitoba both men and women accepted any employment which could be

secured. Some of the men were sent forward to their reserves, and. under

the direction of experienced axemen provided by the government, they

erected houses for the rest of the immigrants. These houses were built

of logs and roofed with sods, while the walls were plastered with clay

both inside and outside. Most of them were heated with the Russian

stove. As fast as the cabins were completed the people were moved to

their reserves, and the earlier arrivals had time to dig up and plant

small patches of their farms. Practically ail of the Doukhobors who took

up land settled in villages, and while some applied for individual

homesteads, the great majority adopted the communal system which they

had known in Russia. In the settlement near the Thunder Hills, which was

known as the "North Colony," there were 13 villages, containing 151

houses and an aggregate population of about 1500. A few hundreds of

Doukhobois located in other parts of Manitoba.

From a material standpoint most of these peculiar people, were

successful, but few of them proved desirable settlers. The strange

religious pilgrimages in which the more fanatical sometimes indulged,

their intractability, their unwillingness to become Canadian citizens

and to fulfill all their homestead duties,

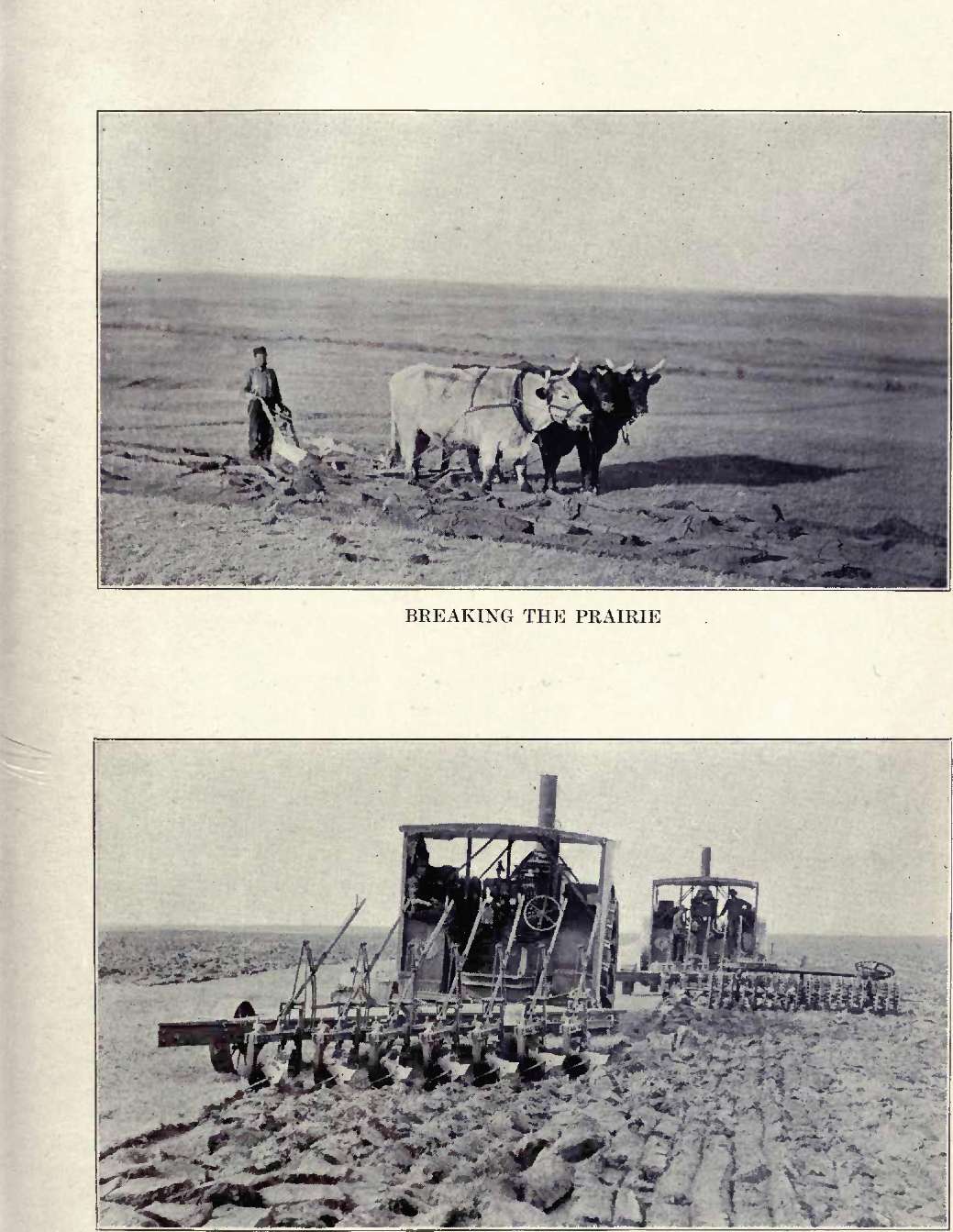

THE SAME TASK, AS ACCOMPLISHED WITH MOTOR TRACTORS

and

their determination not to conform to some Canadian laws gave constant

trouble to the authorities and made the Doukhobors a menace to good

order in the community. Many of them left their lands and went

elsewhere, but they have proved troublesome settlers wherever they have

located. The experiment of transplanting thousands of a peculiar

religious sect and placing them in isolated colonies in a new country is

interesting to the student of sociology and history, but it is safe to

say that the government will not repeat it.

The

last decade of the nineteenth century saw the beginning of another

migration of Slavonic people to Manitoba. These immigrants came from the

provinces of Galicia and Bukowina, which lie beyond the Carpathian

Mountains and form the northeast corner of the Austrian Empire. Most of

them were peasant farmers, who wished to improve their circumstances by

moving to a country where they could secure cheap land. Many of them

brought a little money with them, and these usually took up land at

once; the others found employment for a time in the towns, on railways

under construction, or in the woods, but m most cases their ultimate

purpose was to become owners of farms. These people began to come to

Manitoba about 1896, some obtaining land at once, others accepting any

employment offered to them. In the next year a small colony was

established in the neighborhood of Yorkton, Saskatchewan, and in

1898 another party arrived and settled in Manitoba. The success of these

pioneers of Ruthenian emigration so encouraged their friends at home

that in 1899 about 3,500 of them came out and settled in the province.

They arrived rather late in the season, but most of them who took up

land were able to raise some potatoes and other roots, and very few of

them required assistance from the government. About 3,000 of these

people came to Manitoba in 1900, and each year since has brought a

larger or smaller addition to the Ruthenian population.

As

the Ruthenians reached Manitoba after all the government land on the

open prairie had been taken up, they were obliged to look in the less

desirable districts for homesteads and land which could be bought at a

low price. For this reason most of them are living in the rougher,

wooded areas bordering on the open prairie. They are found along the

eastern side of the province in the districts drained by the Brokenhead

and Whitemouth Rivers; they live in the district lying north of the

older Icelandic settlements between Lakes Winnipeg and Manitoba; they

have settled around Lake Dauphin and on the slopes of the Riding

Mountains; they have farms in the neighborhood of Shoal Lake and

Russell; and they have several settlements near Sifton, Ethelbert, and

other places in the country lying west of Lake Winnipegosis.

Coming during the same period as the Galicians, other Slavonic

immigrants have helped to swell the population of Manitoba. Quite a

large number of Bohemians, who migrated from their own country to

Galicia years ago, have moved from it to this province. Several thousand

Polish people, seeking a country where their energy would have a wider

field, have settled in Manitoba. The majority of both Bohemian and

Polish immigrants are anxious to become landowners, and they have

naturally located in the districts settled by their race-relatives, the

Galicians. While the majority of these Slavic people have gone on the

land, a considerable number live in the cities and towns, and the Slavic

population of Winnipeg must number several thousands.

Many German people have settled in Manitoba, but they have seldom come

from their native country in large parties. Some of them locate in the

towns, but most of them become farmers, and many have taken up land in

the districts occupied by Ruthenians. The number of immigrants coming

from France has not been so large as might be expected. For the most

part they have settled in parts of the country previously occupied by

French-speaking people, although a few new districts have been largely

settled by them. Considering the very dense population of Belgium,

Manitoba has received few settlers from that country. The Belgians

generally settle among the French people of the province. The population

of Manitoba includes several thousand Italians, although few of them

have become agriculturists. They seldom have the means to begin farming

when they reach the country, but they are very industrious and

economical and soon achieve success in other occupations.

It

must not be inferred that these foreign immigrants were the only

settlers who came to Manitoba during the past twenty-five years. The

number of English-speaking settlers has generally exceeded that of the

foreign immigrants. Each succeeding year has brought thousands of them

from Ontario. Quebec, and the Maritime Provinces, from Great Britain and

Ireland, and from the United States. They have changed the unfilled

prairies to well-kept, fruitful farms, built the towns of the province,

developed her industries, moulded her institutions, and guided her

progress; and her future destiny is in their hands. |