|

The

history of French exploration in Canada is inseparably connected with

the history of Roman Catholic missions. "Wherever the explorer went,

there the missionary went; and not infrequently the missionary himself

was the explorer. This combination of colonization with missionary

enterprise gave a peculiar trend to the early history of Canada; and

while historians may differ in their estimates of the benefits which the

country derived from it, there can be but one opinion m regard to the

splendid courage, endurance, and self-sacrifice of the mission pries

themselves. There are no more heroic figures in our history than the

priests who travelled far into the unknown wilderness, ministering to

the spiritual needs of the whites, teaching the rudiments of religious

truth to the Indians, and collecting a vast amount of information in

regard to the places and races which they visited.

When Radisson and Groseilliers made their trading trip into the unknown

wilds of Minnesota in 1659, Father Menard accompanied them, seeking the

remnant of an Indian tribe which he had known during long years of

service among the Hurons and Iroquois. A tribe of Hurons, known as the

Tobacco Indians, had dwelt near Nottawasaga Bay; but to escape utter

annihilation at the hands of their ruthless foes, the Iroquois, the

survivors of the tribe crossed to the south side of the Great Lakes.

Wandering far to the west, the fugitives came in con tact with the

Sioux, and, retreating, before the attacks of these fierce warriors,

they hid themselves in the forests near the sources of the Black River

in Wisconsin. Leaving Radisson's party in October, 1660, Father Menard

went to visit these refugees. He accompanied them in later wanderings

west; and while it is scarcely probable that he ever crossed the borders

of Manitoba, there is an un confirmed story that on one occasion he

reached the sources of the Mississippi River. His last letter to his

superiors was written in June of 1661, and before the end of that year

he had perished, either from starvation or at the hands of the Sioux.

In

the year of Father Menard's death the French government sent the Sieur

de A'alerie from Quebec to Hudson Bay to take possession of its shores

for France. Fathers Claude Dablon and Gabriel Diuillettes were asked to

accompany him and established a mission among the Crees. They set out in

May, 1661; but as they returned before the end of the year, it is not

certain that they actually reached the bay. It is said that Father

Couture was sent to the bay on a semi-political mission a little later,

but it is not certain that he made the trip.

In

1671, Talon sent Paul Denys de St. Simon to Hudson Bay to warn the

English traders there that France claimed the country, and Father

Charles Albanel accompanied him. They reached the mouth of Rupert s

River about the end of June, 1672, and were entertained by the officer

of the Hudson's Bay Company in charge of Port Charles; but it is not

probable that they went far enough west to reach Manitoban territory,

for they returned the same year. Father Albanel has left an interesting

account of the journey. In 1674 he was sent back to resume his

missionary work and remained there until the English deported him in

1675. With other French prisoners, Father Albanel was carried to England

and then sent to France. Although he returned to Canada in 1676, he did

no further missionary work on the shores of Hudson Bay.

When the intrepid de Troyes, assisted by d'Iberville and his brothers,

led an expedition against the English forts on the bay early in 1686,

Rev. Antoine Silvy. who had been on the coast as a missionary some years

earlier, accompanied the force as its chaplain. He has given us a vivid

account of the romantic exploits of this band of adventurers. When the

main body returned to Quebec, Father Silvy remained at Fort Ste. Anne

(Albany) to act as chaplain for the small garrison left there and to do

some mission work among the native tribes. It is quite possible that he

went as far west as the present boundary of Manitoba, for he remained on

the coast of the bay until the beginning of the year 1693. During the

last eighteen months of his stay he was assisted by Father Delmas. The

winter of 1693 was a tragic time for the little garrison at Port Albany,

and on March 3, Father Delmas was murdered by one of its members. It

will be remembered that the insane and shackled murderer was the. only

man found the fort by Captain Grimington when he took the place in the

spring.

Rev. Pierre Gabriel Marest, a native of Laval. France, came to Canada in

1694 and accompanied the expedition, commanded by d'Iberville, which was

sent to Hudson Bay that year to put an end to British dominion there.

Father Marest wrote an interesting account of the voyage and of the

capture of Fort Bourbon (Nelson). He seems to have remained there as

chaplain of the garrison and to have been taken prisoner by the English

when they recovered the place in 1696. He was taken to England, but

afterwards came back to Canada and was sent to the mission at Kaskaskia

on the Illinois River.

When la Verendrye's first expedition set out in 1731, it was joined at

Michilimackinac by Father Mesaiger, wlio accompanied it to the head of

Lake Superior. La Yerendrye and some of his men spent the winter there,

and the priest stayed with them; but in the spring they all went forward

to Fort St. Pierre, the post which the advance party had established at

the outlet of Rainy Lake. Father Mesaiger remained there a year, and

while it is not recorded that he established any missions among the

Indians, it seems quite probable that he visited the eastern part of

Manitoba during his stay,, His successor was RevJ Jean Pierre Aulneau,

who made his headquarters at Fort St. Charles not far from the Northwest

Angle of the Lake of the Woods. In a letter written from this post on

April 30, 1736, he says that lie reached it on October 23, 1735; that he

thinks it must be 300 leagues from the head of Lake Superior, that he

has made considerable progress in mastering the Cree language and has

learned a little of the speech of the Assiniboines, and that he intends

to go down to Lake Wirnipeg and possibly on to Hudson Bay. But the plans

of the young priest were not to be carried out. Tn June he set out for

Lake Superior with the party which la Verendrye sent thither with his

son Jean, and he was among those murdered by the Sioux at the place now

called Massacre Island.

In

1743 Rev. Claude Godefroy Coquart reached Port de la Reine, which la

Verendrye built in 1738 near the present town of Portage la Prairie. He

remained there a year or more as chaplain of the little garrison, but we

are not told that he attempted any missionary work among the Indians.

There is ground for believing that a French priest spent some time in

one of the forts built near the mouth of the Souris river about the

middle of the eighteenth century, since the neighboring Indians

afterward gave accounts of the religious services which he conducted and

repeated French words which they had learned from him.

French exploration and French trade in what is now called Manitoba

ceased soon after the middle of the eighteenth century, and missionary

effort ceased with them. It was more than fifty years before the

Catholic church resumed its missionary work in the far west, and then,

strangely enough, the revival of its activity was largely due to

encouragement received from a Protestant, the Earl of Selkirk. The earl

was anxious that his colonists should be provided with religious guides

and teachers. Father Bourke. went with the first party of settlers and

spent the winter of 1811-12 with them at York Factory; but instead of

going on with them to the Red River in the spring, he went back to

Ireland. Efforts were made to secure the minister whom the Earl had

promised to the Presbyterians of his settlement, but for some reason the

man of their choice did not come. The many misfortunes of the colony and

its uncertain future may have deterred clergymen from undertaking work

in so remote a field. When the Earl visited his settlement m 1817, he

was more deeply impressed than ever, not only with his colonists' need

of a pastor but also with the necessity of securing missionaries for the

considerable number of Metis in the country.

We

find that Lord Selkirk wrote to Miles Macdonell early in 1814 expressing

regret that he had not been able to find a Roman Catholic priest for Red

River y and we find that Macdonell himself, while waiting in Quebec for

his trial during the summer of 1815, had an interview with Mgr. Plessis,

Bishop of Quebec, in which he urged that a French priest should be sent

to the colony. lie believed that a priest from Canada would be far more

acceptable to the Roman Catholics of Red River than one from Ireland or

Scotland; and the Earl of Selkirk strongly endorsed Macdonell's

suggestion in a letter which he wrote to Bishop Plessis on April 16.

1816. During his visit to the settlement in the following year he

advised the French-speaking people to address a formal petition to

Bishop Plessis, asking for a resident priest. This was done; and the

petition, signed by J. Bte. Marsolais, Louis Nolin, Augustin Cadotte,

and twenty others, reached Mgr. Plessis on February 11, 1818. The bishop

was impressed with the importance of the work suggested, but he lacked

men and money to carry it on. However, he made an effort to secure

volunteers for the far-off field and selected a man whom he considered

well fitted for the work there. When Lord Selkirk returned from Red

River he again urged that missionaries be sent to the Metis, and to aid

the proposed mission he gave twenty square miles of land as a kind of

endowment for it, as well as twenty-five acres beside the Red River as

the site of a church.

Rev. Joseph Norbert Provencher, whom Bishop Plessis had chosen as a

missionary to Red River, finally consented to undertake the work which

his superior wished to assign him; and on May 19, 1818, he set out for

his new field, accompanied by his colleague, Rev. Severe Dumoulin. They

followed the canoe route of the early fur-traders, going by way of the

Ottawa River, the Great Lakes, and the water-ways between Lake Superior

and the prairies. On the morning of Julv 16 a horseman, riding up beside

the Red River, saw a little flotilla of canoes coining up the stream. He

galloped up to Fort Douglas with the news, and when the two missionaries

stepped ashore there about mid-afternoon, most of the people living in

the vicinity were waiting to greet them. Guns were fired cheers were

given, and many hands extended to welcome the pioneer missionaries of

Red River. They became the guests of the acting governor, Mr. Alexander

McDonell; but that (lid not mean luxurious living, for almost the only

viands on the gubernatorial table were dried meat and fish. There was

neither bread, milk, nor butter; and tea and sugar were rare luxuries.

The

missionaries held their first service 011 July 3!), using a small

building as a temporary chapel. In a few days they began the

construction of a building, 50x30 feet, on the beautiful site donated by

Lord Selkirk. This building was to serve as church, school, and priest's

residence. By the end of August the log walls had been raised}-but the

roof proved more difficult, for the only boards obtainable were poplar

boards of poor quality, and neither shingles nor nails could be found in

the settlement. So Father Provencher partitioned off twenty feet at one

end of his building, boarded the roof over that part, laid a good

coating of clay on the boards, and covered the clay with rushes. The

rest of the structure remained roofless until the following year. The

covered part was divided into two rooms, and early in September the

missionary could write to his bishop, "I have a little room and a little

chapel." Stoves and glass were unknown in the colony at that time; but a

fireplace, built of stones and clay served as an inadequate heating

apparatus, and parchment took the place of glass in the windows. Such

was the first church building in Manitoba.

In

September Father Dumoulin was sent to the Metis settlement at Pembina,

where he built a church, school, and dwelling. He remained in charge of

this mission for nearly five years. Father Provencher visited it early

in 1819, and in March he made a tour of some of the trading posts cn the

QuAppelle and Souris Rivers. In the summer he made a missionary journey

to Lake Winnipeg, while Father Dumoulin visited different points on the

Lake of the Woods. During the summer Father Provencher appealed to

Quebec for more helpers, and in the following summer Rev. Pierre

Destroisniaisons and Mr. Sauve reached the settlement. The former took

charge at St. Boniface while Father Provencher went to Canada, and the

latter was sent to take charge of the school at Pembina. Father Dumoulin

made a visit to Hudson Bay during that summer of 1820.

At

a meeting of the council of the Hudson's Bay

Company held at York Factory early in July,

1820, it was decided to make an annual grant of £50 for the support of

the mission at St. Boniface, and hoping to obtain further aid in men and

money for the work which he had undertaken, Father Provencher set out

for Canada on August 16. It was two years before he returned, and then

he came as a bishop, having been consecrated in May, 1822. "With him

came Jean Harper, soon afterwards ordained as a priest, who was to labor

in the settlement for nine years, teaching in the school at St.

Boniface, preaching at the adjacent missions, or following the buffalo

hunters to the plains as their religious guide and the teacher of their

children. Thus the new bishop of a diocese larger than the half of

Europe had two priests and two teachers to help him in his work.

SOME OF BRANDON'S CHURCHES

Before leaving for Canada. Bishop Provenoher had made plans for a new

chapel and a residence, and some of the material had been procured; but

when he returned, lack of funds compelled him to stop the work being

done on these buildings. In 1823 most of the Metis living at Pembina

removed to the White Horse Plains on the Assiniboine, because Pembina

was found to be south of the international boundary, and Pather Dumoulin

went back to Canada. In the following year the parish of St. Francois

Xavier was organized at White Horse Plains, and Father Destroismaisons

was placed in charge of it. During these years both Father Provencher

and Father Dumoulin had been more than preachers and teachers. They had

striven to wean the Metis from the hunter's life and to teach them

agriculture; both often labored in the fields, planting and cultivating

seeds and fruits which they had obtained from Canada.

In

spite of severe winters, floods, and the occasional scarcity of food,

the Roman Catholic missions in the Red River Settlement made progress.

The stone residence of the bishop at St. Boniface, commenced in 1828,

was finished two years later. In 1820 a part of the material for a new

stone cathedral was secured, and the foundation was laid in 1833; but

the work, often suspended for lack of funds and as often resumed, was

not completed until 1837, This is the church with "turrets twain," which

was burned in 1860. To secure aid for the work Bishop Provencher visited

Canada in 1830. While there he learned that a religious society in

France had made a grant of money for his mission; and when he returned

to St. Boniface in 1832, he brought with him Rev. George Belcourt, whose

aptitude for acquiring Indian languages fitted him in a special way for

mission work among the native tribes. Father Bel-court opened a mission

at Baie St. Paul in 1834, visited the Indians of Rainy Lake in 1838,

established a mission at Wabassimong (White Dog) on the Winnipeg River a

little later, and organized a mission at Duck Bay on Lake Manitoba in

1840. Then followed nine years of labor at St. Boniface and

other-places, and ten years at Pembina anil different points in United

States territory.

Rev. Charles Poire also came to Red River in 1832 and was placed in

charge of the mission of St. Francois Xavier In the following year Rev.

Jean Bap-tiste Tlrbault arrived. He taught in the school at St. Boniface

and had charge of the mission there during the bishop's absence: he

spent a year at St. Francois Xavier and another at Duck Bay the made a

journey to the Rocky Mountains in 1842, and in 1844-5 he made another

which took him to Lesser Slave Lake; other mission work filled the busy

years, and it was not until 1869 that Father Thibault returned to

Quebec. Even then his service in Manitoba was not quite ended, for he

came back in 1870 to assist the Canadian government in pacifying the

insurgent Metis.

In

1835 Bishop Provencher journeyed to Canada once more to secure men and

money for work in his great diocese., From Canada he went to England,

and from England to France and Italy, and it was 1837 before he returned

to St. Boniface. It was very difficult to secure missionaries for such

remote fields of labor, and yet the bishop planned to establish missions

on the Columbia River and in the far northwest and to find more priests

and teachers, as well as members of some religious sisterhood, for his

work in the Red River country. In a few years manv of his hopes were

realized. Two missionaries were sent to the Columbia in 1838. A journey

to the United States and Canada in 1843 brought several new clergy to

his Held, and in 1844 four of the Grey Nuns came from Montreal to teach

in the girls' school at St. Boniface and to care for the sick. Rev.

Alexandre Tache arrived in 1845, and a year later he and a colleague

were sent to a mission at lie a la Crosse. By this time there were

organized parishes or missions at St. Boniface, Baie St. Paul, St.

Francois Xavier, Buck Bay, The Pas, Lake Winnipeg, and Winnipeg River in

Manitoba, in addition to those in other territory, near or remote.

In

1851 Bishop Provencher selected Father Tache as his coadjutor, and the

young priest came from his distant field about the sources of the

Churchill River and went, to France to be consecrated. When he returned

to Manitoba in 1852, Father Lacombe, who had spent a year at Pembina

some time before, accompanied him. Bishop Tache went back to his mission

at lie a la Crosse; but he had been there less than a year when he was

recalled, to St. Boniface to take charge of the diocese, for Bishop

Provencher, the father of Roman Catholic missions in Manitoba, passed

away cn June 7, 1853. Under his able successor mission work was

prosecuted more vigorously than ever, new churches were built, new

schools were organized, and hospitals and orphanages were founded; but

the story of these achievements cannot be told in a single chapter.

Lord Selkirk seems to have been unable to send a minister to his colony

beside the Red River, and the Hudson's Bay Company denied all

responsibility in the matter after it took back from the earl's

executors his great estate of Assiniboia. Nevertheless, the company was

not unmindful of the value of missionary work among its servants and the

many Indian tribes in its territory, and in 1820 it sent Rev. John West

out to Fort Douglas in the capacity of chaplain. He seems to have come

in a double capacity, being recognized also as a missionary by the

Church Missionary Society. He arrived in the settlement on October 14,

and as soon as possible secured a building to be used as a temporary

chapel and commenced his pastoral work among the people. The Hudson's

Bay Company gave two lots of land for church purposes, and on one of

these a church, a school, and a residence were begun during the summer

of 1821. Mr. West did riot confine his work to members of his own

church, the Church of England, but strove to make his ministrations

acceptable to the adherents of all faiths represented in the population

of the colony. Nor was his work confined to the settlement. He made a

number of missionary journeys to various trading posts of the company

west and north. On these journeys he did what work was possible among

the Indians as well as the whites whom he met. The little church which

he established became St. John's Church, the mother church of the Church

of England in the west.

Mr.

West returned to England in 1823, meeting his successor. Rev. David

Thomas Jones, at York Factory. This clergyman came out as a missionary

of the Church Missionary Society and carried on the work in the colony

much as Mr. West had done. He established a second church, a few miles

north of St. John's, subsequently called St. Paul's. Mr. Jones became

the chaplain of the Hudson's Bay Company in 1825, and then the C. M.

Society sent out Rev. William Cochran as its missionary at Red River. He

was a man of decided opinions and tireless energy—the typical pioneer

missionary who could turn his

hand to any kind of work. For forty years he labored up and down the

country, the real founder of the Church of England in Manitoba. He and

Mr. Jones worked together in the two existing churches for a year, and

then the latter went home on a visit, leaving all the work to Mr.

Cochran. Mr. Jones came back in 1827, and then Mr. Cochran moved down

the river to a settlement which was growing into importance near St.

Andrew's Rapids, and there he built a church, which was finished in

1831. It was afterwards known as St. Andrew's Church, but at the time it

was often called the Lower Church, St. John's being designated the Upper

Church and St. Paul's the Middle Church.

The

condition of the Indians appealed strongly to Mr. Cochran. In 1833 he

established a mission among the natives living along the lower part of

the Red River, and three years later he completed a church in which his

dark-skinned converts might worship. This was known as St. Peter's

Church. Mr. Cochran was more than a preacher; on occasion he could lend

a hand in the erection of a building, and he was a practical teacher of

agriculture. He instructed the Indians of St. Peter's mission in the

arts of settled life as well as the principles of religion; and at the

end of several years of incessant effort among them he could write, with

justifiable pride, that there were "twenty-three little whitewashed

cottages shining through the trees, each with its column of smoke

curling up to the skies, and each with its stacks of wheat and barley.

Mr.

Cochran seems to have had charge of all the churches along the river,

except St. John's, for some time, and the departure of Mr. Jones in 1838

left St. John's to the care of the indefatigable missionary; but in the

following year t Rev. John Smethurst relieved him of St. Peter's

mission, and in 1841 Rev. Abraham Cowley took charge of St, Paul's for a

short time. In 1844 Rev. John Maeullum reached the colony and became

pastor of St. John's. I)r. Mountain, bishop of Montreal, who visited the

country in 1844, reported that the four churches—St, John's, St. Paul's,

St. Andrew's, and St. Peter's—were attended by 1,700 persons, and that

there were nine schools, attended by 485 scholars, in connection with

the churches. In the meantime the Indians were not forgotten. Henry

Budd, an Indian educated in Mr. "West's school, had opened a mission

among the Crees around Cumberland House in 1840, and soon afterwards

Rev. Mr. Cowley established an Indian mission at Fairford oil Lake

Manitoba.

The

time soon came when the need of some one to direct and supervise the

work of these clergymen was felt. In 1838 Mr. James Leith, a retired

chief factor of the Hudson's Bay Company, died, leaving £12,000 to be

devoted to mission work in Rupert's Land. The trustees appointed by his

will secured an order from the court of chancery, permitting them to use

this bequest as an endowment for a bishopric of Rupert's Land. The

Hudson's Bay Company promised a yearly grant of £300 towards the support

of such a bishopric, if it were established, and thus a considerable

revenue for the see was assured. The see of Rupert's Land was

accordingly established by letters patent, the Archbishop of Canterbury

being declared its metropolitan for the time being; and on May 29, 1849,

Rev. David Anderson was consecrated as its first bishop. Bishop Anderson

reached Fort Carry in the following October.

In

1851 the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel sent out Rev. William

H. Taylor as a missionary to Rupert's Land, and he was given charge of

St. James, a new parish organized just west of Winnipeg. In the

following year Rev. Mr. Cochran, who had been made archdeacon of

Assiniboia, secured a "tract of land from an Indian chief at Portage la

Prairie, and in the following year he induced a number of people to

settle on it. By 1853 he had built a church and a school there, the

church being known as St. Mary's. Within a few years he had organized

St. Margaret's at High Bluff and St. Ann's at Poplar Point. Holy Trinity

church at Headingly was built in 1854, and its first incumbent was Rev.

C. 0. Corbett. In 1852 Bishop Anderson visited Moose Fort and

established a mission there.

In

1856 the Bishop of Rupert's Land visited England and obtained money for

the erection of a new cathedral at St. John's—the building which, in

spite of various misfortunes, is still in use. In 1864 Bishop Anderson

resigned and returned to England. At that time he. had more than twenty

clergy under him, some acting as missionaries in the far north and

northwest and others in what is now Manitoba. Beside the parish churches

there were missions at York Factory, Fort Alexander, Fort Ellice, Swan

Lake, and Fairford. The greater part of the money needed for the support

of these churches and missions was contributed by various church

societies in England.

Right Reverend Robert Machrav, the second Bishop of Rupert's Land,

reached the country, in which he was to labor for the remaining

thirty-nine years of his life, during October, 1865. He set out in a few

weeks to visit the parishes and many of the missions in his diocese and

make himself personally acquainted with their needs. He encouraged

better organization in the parishes and strove to make more of the

churches self-supporting. From the first he insisted on the importance

of better schools. The details of the work which he did as a bishop, an

educationist, and a far-sighted, patriotic citizen cannot be given in

the space at our disposal. The country at large, as well as his church,

owes much to the late Archbishop Machray.

The, Hudson's Bay Company was organized as a commercial corporation, but

conditions existing in the great territory which it controlled compelled

it to be something more. It became a governing body; and while it was

neither a missionary society nor an educational organization, it aided

both missions and schools. Whatever the motive from which the aid was

given, it often promoted the welfare of the white settlers and the

native tribes in Rupert's Land, as well as that of the company's

employees. It was not inconsistent with the policy of the company to ask

the English Wesleyan Missionary Society to open missions in its great

domain about Hudson Bay; and in 1840 this society responded by sending a

number of men to labor in the remote interior of the country. One of

these was Rev. Robert T. Rundle, who was to proceed to Norway House and

afterwards carry the gospel to the Indians in the far west; and another

was Rev. Mr. Mason, who was to labor in the district about Rainy Lake.

Rev. James Evans, who had done ten years of mission work among the

Indians of Upper Canada and who had been preaching to the Rainy Lake

tribes for two years, was transferred to Norway House to take charge of

the mission to be opened there.

Rev. Mr. Evans reached Norway House during the summer of 1840, taking

with him two native assistants. One was Henry B. Steinhauer, who had

taken the name of the gentleman who had furnished him with the means to

obtain an education, and the other was Henry Jacobs. The latter remained

at Norway House for two years and then went to England to be ordained.

He returned in 1843 to spend several years in mission work at various

points in the west. The report that a missionary had come to Norway

House attracted the Indians thither; and on the advice of Mr. Ross, the

factor of the Hudson's Bay Company, a native village was established on

the shore of Little Playgreen Lake opposite to the company's post.

Rossville was the name given to this village. Here a tract of land was

cleared, cottages built, fields laid out, and some cultivation of the

soil attempted. A church and a school were soon erected, and in a short

time Rossville became a somewhat settled Indian community, not unlike

that which Archdeacon Cochran had established at St. Peter's a few years

earlier. The Rossville Indians had to depend on hunting and fishing for

a livelihood for some time; but under the direction of Mr. Evans they

gradually learned to plant and sow the cleared ground and secure a part

of their living by agriculture. Mrs. Evans tried to do as much for the

women as her husband was doing for the men.

To

Mr. Evans must be given credit for an achievement, which does not seem

to have been attempted by any earlier missionary—the reduction of the

Cree language to a written form. Many of his Indians were obliged to

move from place to place, hunting, fishing, or trapping, and he was

anxious to devise some means whereby they could carry with them in

printed form the truths which he had taught them. After much study of

the Cree language he found that its words, when resolved into syllables,

gave thirty-six distinct syllabic sounds; and he then devised a very

ingenious syllabic alphabet of thirty-six characters in which, with the

aid of a dozen terminal symbols, the Cree language could be written.

These syllabic characters could be mastered by the natives in a few

hours, and then they were able to read. The use of the new written

language spread rapidly among the Indians, and at the present time it is

no uncommon thing for the traveller in the northern wilds to find at the

end of a portage or at some point on a forest trail a bit of birch bark,

held in a split twig and inscribed with Evans' Cree characters, which

gives some information or asks that a message be taken to some one at a

distance.

It

was not easy for Sir. Evans to provide reading matter for his pupils;

but after a time sheets of birch bark, on which bible texts and hymns

had been written, were in circulation among them. The demand for them

could not be supplied in that way, however, and Mr. Evans determined to

print the matter which he wished to place in the hands of the Indians.

He had neither type nor printing-press, but the lack of these things did

not deter him from carrying out his plan. Models of the type needed were

carefully carved, moulds were made of clay, and lead furnished the

necessary metal. When the type had been cast and a page of reading

matter had been set up, a fur press furnished the power necessary to

give a distinct impression on such paper as could be obtained or on the

thin birch bark sometimes used as substitute. The work done in this way

was very wonderful to the Indians, and accounts of it soon spread far

and wide among them. The story reached the ears of scholars in the

outside world and roused much interest; and it was not long before the

Wesley an Missionary Society sent Mr. Evans a supply of type, a hand

press, and £500 for the erection of a suitable building in which to do

his printing. Translation and publishing then went on apace, and

considerable portions of the Bible, many hymns.

and

a catechism were soon printed in the Cree language and put into

circulation. Since that time Mr. Evans' syllabic characters, with a few

additions, have been adopted in reducing other Indian languages to

writing.

As

soon as his work at Norway House had been organized, Mr. Evans made

missionary journeys to other parts of the country such as .Moose Lake,

The Pas, Shoal River, Fort Pelly, Beaver Creek, Red River, Fort

Alexander, Beren's River, and Oxford House; and in later years he

travelled far to the northwest, going to Fort Simpson on one occasion.

On a trip to Fort Chippewayan the accidental discharge of a gun in Mr.

Evans' hands led to the death of one of his canoemen, an Indian named

Hassel. The party returned to Norway House at once; but some time

afterwards Mr. Evans decided to go to Lake Athabasca and surrender

himself to the relatives of the man whom he hail accidentally killed.

The purpose was carried out; and although many of the relatives wished

to kill him, the mother of the dead man interceded for the missionary,

and his life was spared. He was adopted by the tribe, remained with it

for some time, and then returned to his work at Norway House. About six

years after the establishment of his mission, Mr. Evans was summoned to

England, and not long after his arrival he died.

The

Wesleyan missionaries had labored among the Indians rather than the

whites. Their work continued, and among other laborers in the far west

we find Rev. George McDougall, a missionary among the Blackfeet. This

man made a visit to Ontario in 1867, and while there urged the

Methodists of that province to send missionaries to organize churches

among the white people of the Red River Settlement, as well as more men

for work among the Indians. In the following year three men volunteered

for work in the west—Rev. E. R. Young, who was sent to Norway House,

Rev. Peter Campbell, who was to assist Mr. McDougall at the foot of the

Rocky Mountains, and Rev. George Young, who was to organize churches in

the Red River Settlement.

The

party set out in May, 1868, and reached Winnipeg on July 4th. A journey

through the settlement along the Assiniboine convinced Mr. Young that a

wide field was open to him. He gathered congregations and organized

classes in many places, and before many years passed he had the pleasure

of seeing Methodist churches established in them. By the end of December

he had secured a building in Winnipeg, which could be used as a

residence and a chapel. During the winter timber for a more suitable

building was brought down the Assiniboine. a lot was secured from the

Hudson's Bay Company, and before the end of August "Wesley Hall" was

ready for use as a mission house and a church. Two years later the

congregation had a better building in which to worship, the first Grace

Church of Winnipeg. Mr. Young's mission field extended from Winnipeg

westward for more than a hundred miles, and in July, 1869, Rev. Matthew

Robison came out to help him in caring for it. Three years later the

first Methodist conference was held in Winnipeg, and it was attended by

nine of the ten ordained Methodist ministers then working within the

limits of the present province of Manitoba.

It

will be remembered that Lord Selkirk promised to send a minister to his

Presbyterian colonists at Red River, that they chose Rev. Mr. Sage as

their pastor, and that, pending his arrival in the settlement, Elder

James Sutherland was authorized to baptize and to marry. But for some

reason Mr. Sage never

came to the Red River Settlement, and after a short residence there .Mr.

Sutherland moved to Canada. For more than a generation there was no

Presbyterian minister in the colony, although the people petitioned the

Hudson's Bay Company again and again to send one. In the meantime the

Church of England had opened several churches along the Red River, and

many of the Presbyterians attended them, the Church of England service

being modified to some extent to make it acceptable to the Presbyterian

members of the congregations. Nevertheless, the Presbyterians kept

repeating the request for a minister of their own faith. As late as

June, 1844, such a petition was placed in the hands of Sir George

Simpson for transmission to the directors of the Hudson's Bay Company in

London. In the following March the settlers received the company's

reply, denying all responsibility for carrying out a promise made by

Lord Selkirk. To this the settlers' committee made a rejoinder in July,

attaching thereto a number of affidavits in regard to the promises made

by the earl and his agents. The company's answer to this communication

was dated from London on June 6,-1846, and seems to have convinced the

settlers that the company would not send them a Presbyterian minister.

They then appealed to their co-religionists, sending to the General

Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland copies of the petitions,

letters, and affidavits which had been forwarded at earlier dates to the

Hudson's Bay Company. This appeal seems to have been repeated, and after

some delay the Scottish church referred the matter to the Free Church of

Canada, asking that a missionary be selected for work in the Red River

colony. The man chosen was the Rev. John Black.

For

a long time the Presbyterians claimed the land on which St. John's

Church had been built because of a statement made by the Earl of Selkirk

during the historic meeting held on the church site in 1817. The matter

was finally settled about 1850, the Presbyterians relinquishing their

claim to the St. John's site and accepting another a few miles down the

river. In anticipation of the arrival of a minister they erected a

building which would serve for a temporary manse and church.

Rev. Mr. Black reached Kildonan on September 19, 1851, and a few days

later held liis first service in the partially completed building, which

his people had put up. Soon after they began to collect material for a

new stone church, and although the work was retarded by the flood of

1852, it was completed in the following year. The Kildonan church still

stands beside the Red River, the oldest Presbyterian church of Manitoba.

A log school was built very soon after Mr. Black came, but this was

replaced by a stone structure in 1864. In 1862 Rev. James Nisbet came

out to assist Mr. Black, and in the following year he took charge of a

church which had been organized at Little Britain. In response to Mr.

Black's appeals the Presbyterian Church of Canada decided to establish

missions among the Indians of the west, and in 1866 Mr. Nisbet moved to

Prince Albert to open a mission there. Other ministers—Rev. Alexander

Matheson, Rev. William Fletcher, and Rev. John McNab—soon came to I)r.

Black's assistance in the Red River Settlement, and new churches were

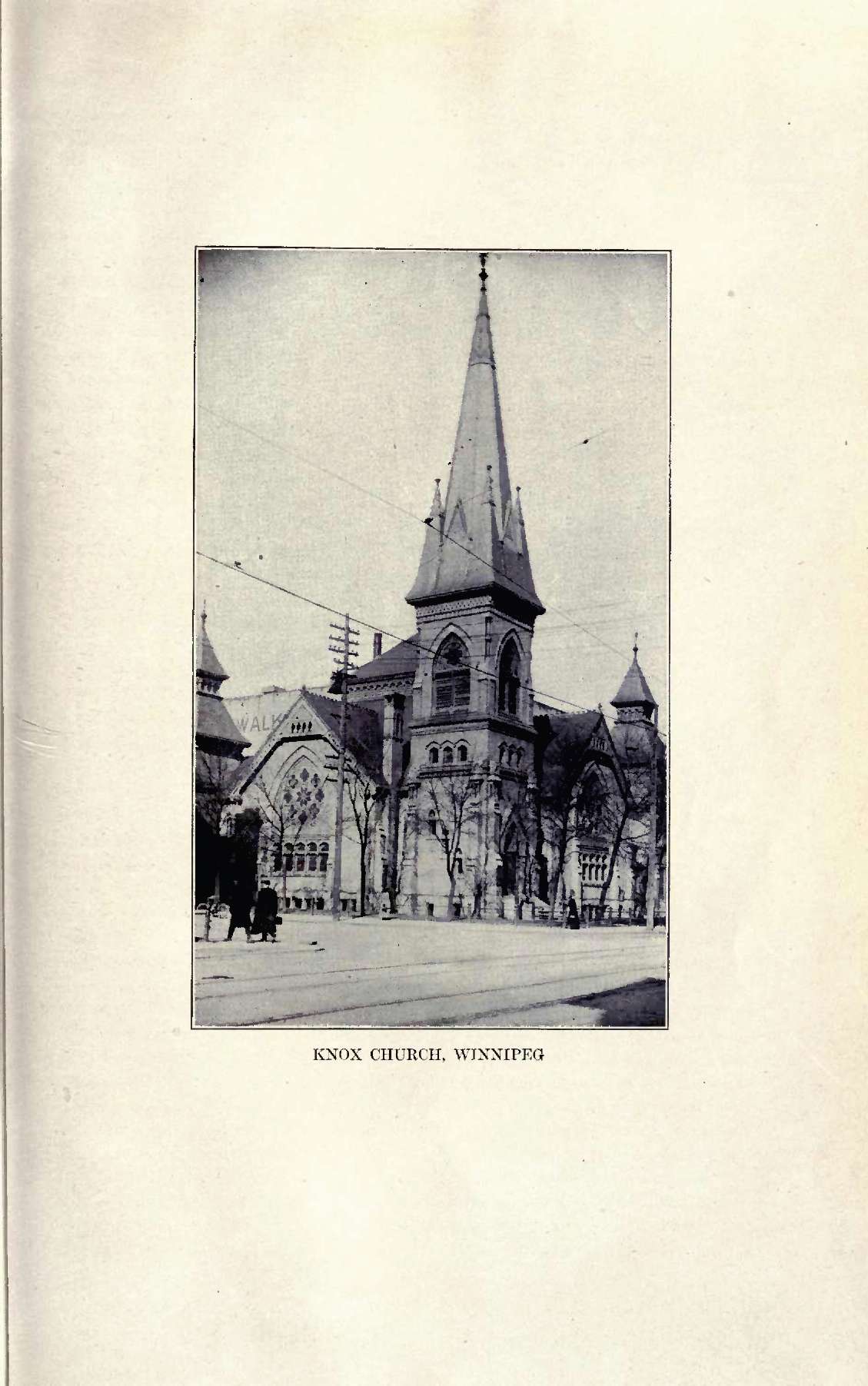

established at various points. Knox Church, the first Presbyterian

church of Winnipeg, was organized in July, 1870. About four years later

Rev. James Robertson became its pastor, and his appointment as general

superintendent of missions in 1881 marked a new era in the history of

Presbyterianism in the west. |