|

The

Hudson's Bay Company seems to have made some provision for educating the

children of factors and servants employed in its northern forts, for in

1808 it sent out James Clouston, Peter Sinclair, and George Geddes to

act as teachers at some of these forts, paying each a yearly salary of

£30. Under the conditions which prevailed in the country, the

instruction given at these posts was not likely to he continuous or

systematic, and it is not probable that any teaching was attempted at

the inland posts previous to the arrival of permanent settlers in the

country. It should be added, however, that many of the company's factors

who had taken Indian wives sent their children to Great Britain or

Canada to be educated. The traders of the North-West Company were

equally anxious to secure a fair education for their offspring, and so

quite a number of the prairie people, in whose veins French or Scotch

blood was mixed with that of the native races, had received a fair

education.

Lord Selkirk was very anxious to provide schools for the children of the

pioneers in the Red River Settlement. As early as 1813 Mr. K. McRae was

appointed to look after their educational interests, and he was expected

to organize a school for boys and another for girls during the following

year. The earl's instructions were: "He (McRae) has the improved methods

of Jos. Lancaster. Let him select some young man of cool temper as

schoolmaster. The. children should learn to read and write their native

tongue (Gaelic). I care not how little they learn of the language of the

Yankees. In the girls' school, needlework and women's accomplishments

should be taught with reading." That the earl's agents shared his

interest in education is shown by the fact that one of them organized a

school for the children on board the ship which brought out the fourth

party of Red River colonists.

Several years went by before Lord Selkirk's plans for establishing

schools in his colony were carried out. The future of the settlement was

most uncertain. Scarcity of food compelled the settlers to migrate to

Pembina when w inter approached, and the hostility of the Nor'-Westers

and the Metis compelled them to migrate to +he foot of Lake Winnipeg or

elsewhere on two occasions during the summer. It is not surprising that

such adverse conditions postponed the organization of schools six years.

In

his charge to the missionaries whom he sent to Red River in 1818, Bishop

Plessis said, "They should apply themselves with special care to the

Christian education of children, establishing schools for this purpose

in all the villages which they have occasion to visit." Father

Provencher was not slow to carry out these instructions, and as soon as

bis mission building at St. Boniface was habitable, he opened a school

there for the children of the neighborhood. This, the first Roman

Catholic school in Manitoba, was opened about the first of September

1818; and there for some hours each day the big, kindly priest taught

the children reading, writing, and the catechism. The little folks

proved apt pupils, and two of the larger lads had commenced the study of

Latin before the close of 1819.

As

soon as the building at St. Boniface was ready for occupation, Bishop

Provencher sent his colleague, Father Dumoulin, to the French settlement

at Pembina to establish a school there. A gentleman from Quebec, named

Guillaume Edge, was put in charge of it, and before the end of the year

sixty pupils had been enrolled. We are told that a school for the

children of the buffalo hunters was organized at a point some distance

west of Pembina soon after,: and that a French Canadian named Legace was

its teacher; but it is probable that the settlement was not permanent

and that the school was closed when the hunting season was over. Mr.

Edge remained in the Pembina school two years, and then Mr. Sauve took

his place. He seems to have remained in charge until 1823, when Pembina

was found to be in United States territory, and most of the settlers

moved to St. Boniface or to points along the Assiniboine.

Father Provencher went to Quebec in 1820, leaving Father Destroismaisons

in charge of his school, and when he came back two years later, he

brought with him Mr. Jean Harper, soon ordained as a priest, who acted

as principal of the school for about nine years. In 1823 Bishop

Provencher reported with some pride that two boys in the school, a Metis

named Chenier and a Canadian named Senecal, had mastered the Latin

grammar. A few years later we find that one of the masters taught

English, so it is probable that some English-speaking boys attended the

school.

But

Bishop Provencher's educational work was not confined to St. Boniface.

One by one, new parishes were organized in different parts of the

country, and many of them had schools, the priest being teacher as well

as pastor. Nor was the bishop unmindful of the educational needs of the

girls in his great diocese. His difficulty was to find teachers for

them; but this was overcome in 1829, when he induced Miss Angelique

Nolin and her sister to come down from Pembina and take charge of a

girls' school in St. Boniface. In 1838, through the generous assistance

of Sir George Simpson, he opened an industrial school in St. Boniface,

two ladies having been secured to give the young women of the settlement

instruction in weaving and other household arts. The school and its

equipment were burned in the following year, but with the help of the

Hudson's Bay Company, its work was soon resumed in another building. In

1844 Sisters Valade, Lagrave, and Lafrance, the first nuns to reach

Manitoba, took charge of the school which the Misses Nolin had managed

up to that time. Sixty girls were attending it then.

Fifty-three years after Bishop Provencher opened his first school in the

ill-constructed building, which served for church and residence as well

as school, the institution was incorporated as St. Boniface College; and

it is now attended by about four hundred students, engaged in secondary

and university studies® In the place of the one girls' school with two

teachers, there are many convents scattered over the province ini which

a very large number of girls are being educated.

MANITOBA MEDICAL COLLEGE

"When Rev. John West, the first missionary sent to Red River by the

Hudson's Bay Company, reached his field, he set at work at once to

organize a school among the Scotch settlers. Jn his

Journal he says.^'Soon after my arrival I got

a log bouse repaired about three miles below the fort (Fort Douglas),

among the Scotch population, where the schoolmaster took up his abode

and began teaching from twenty to twenty-five children.'' This school,

which was opened about the first of November, 1820, was probably the

first school for English-speaking children organized in the Red River

Settlement. The teacher was a gentleman named Harbidge or Halbridge, who

had reached the colony just before the school was opened. In 1821 quite

a large tract of land was secured, and an attempt was made to erect

school buildings upon it. They were not completed when autumn came, and

during the winter the school was conducted in a building belonging to

the North-West Company. Owing to its distance from Kildonan, the

attendance of the Scotch boys fell off badly during the severe weather.

In 1822 the new buildings were occupied; and Mrs. Halbridge, who came

out to her husband that year, taught the girls of the settlement

household science as. well as reading and writing. Many of the boys in

attendance came from a distance, and it was necessary to build a

residence for them. The lads were instructed in the rudiments of

agriculture, and Mr. West speaks with pride of the wheat and potatoes

grown on the school grounds. lie seems to have had a few head of cattle

too, so that his school was an agricultural school in a small way.

Rev. Mr. West went home to England in 1823, and his successor, Rev. T.

D. Jones, seems to have managed the school for the next two years. Then

he went back to England for a visit, and Rev. W. Cochran came out to be,

as he said, "minister, clerk, schoolmaster, peacemaker, and agricultural

director." The school seems to have developed into the Red River Academy

about 1833, and under the management of Rev. John Macallum it did good

work for the youth of the colony for many years. That gentleman was in

charge of it when Bishop Anderson arrived in 1849; but some years later

the bishop found the expense of maintaining the school too great for the

limited funds at liis disposal, and it was closed. Its lineal successor

seems to have been a similar school in St. Paul's parish, which was

conducted by Rev. S. Pritchard, a son of the Mr. John Pritcli-ard who

was prominent in the early history of the colony. This school was in

operation when Bishop Machray reached the country in 1865.

In

the meantime educational facilities for the English-speaking girls of

the small and remote colony had greatly improved. The wife of Rev. David

Jones, who had joined her husband at Red River in 1829, was impressed

with the need of a boarding school for the girls of the settlement and

for the daughters of Hudson's Bay Company's factors living in other

parts of the country. She soon opened such an institution and, assisted

by a governess from England, taught in it until her death in 1836. Then

the wife of Rev. John Macallum took charge of the school until her

husband's death in 1849. Cupid seems to have interfered with the

management of this school very often; for no sooner was an assistant

teacher brought out from England than she was induced to become the wife

of some lonely officer of th& Hudson's Bay Company. In 1851 a new

building was erected for the school on the north side of the creek which

flowed into the Red River just south of St. John's cathedral; and Mrs.

Mills and her two daughters took charge of it. This school was closed

ill 1858, but its place in the life of the community was taken by a

school which the Misses Davis opened in St. Andrew's. Many ladies now

living in Manitoba received their education in that institution.

As

the clergy of the Church of England extended the field of their labors

north along the Red River and west along the Assiniboine, new parishes

were organized and a number of new schools established. One of the most

important was at Portage la Prairie. About 1851 Archdeacon Cochran

purchased the land on which the town now stands from the Indian chief,

Pe-qua ke-kan, and in the following year a number of people from Red

River moved west and formed a new settlement. As soon as his church and

rectory were erected, the energetic archdeacon built a log school, and

in it Mr. Peter Carrioch taught the children of the settlement for three

years. He was followed by the archdeacon's son, Rev. Thomas Cochran, and

he in turn by Mr. J. J. Setter, afterwards sheriff of the district.

Bishop Machray took charge of the diocese of Rupert's Land in 1865. From

the day of his arrival the importance of schools was always in his mind.

In his first conference with his clergy he urged that a school should be

maintained in every parish. Above all, he was anxious to reopen the

school at St. John's. He had a principal in mind from the first. "My

heart is set on an old college friend," he wrote; "1 feel sure he would

be quite a backbone to our whole system." That friend was Rev. John

McLean. So the old school was revived, Mr. Pritchard's school was

amalgamated with it, and the new institution was opened as St. John's

College on November 1, 1866. It was incorporated by the legislature in

1871.

The

pioneer missionaries of Manitoba were educationists, and Rev. John

Black, the first Presbyterian clergyman to settle in Manitoba, was no

exception to the rule. He came to Kildonan in 1851, and as soon as his

church and manse were built, a school was erected, in which the pastor

himself was one of the teachers. For twenty years this school served the

community, and then it was transformed into Manitoba College. Rev. Dr.

Bryce and the late Rev. Thomas Hart, D. D., were its first professors.

The college was incorporated in 1871, and a few years later it was

removed to Winnipeg.

It

was somewhat late m the history of the Red River country before the

Methodist church undertook missionary and educational work in it; but in

1873 Rev. George Young opened a small school in Winnipeg and placed Mrs.

D. L. Clink in charge of it. Later in the year he came back from Ontario

with money and equipment for a larger school. A building was erected on

the lots now occupied by (Trace Church, and in it the Wesleyan Institute

was formally opened on November 3, 1873. with Rev. A. Howerman as

principal. In 1877 the legislature passed a bill to incorporate Wesley

College, but the Wesleyar Institute does not seem to have had the

standing required for affiliation with the university, and instead of

being transformed into Wesley College, it was discontinued. It was ten

years before the Methodists organized a college and affiliated it with

the provincial university.

Of

course there were no public schools in the province when it was

federated with Canada: but during the first session of the first

legislature an Act to Establish a System of Education in the Province

was introduced. It received its second reading during the afternoon of

May 1st. After a little discussion it was referred to committee, and on

the evening of the same day was reported to the house, read a third

time, and passed. Two days later it received the assent of the

lieutenant-governor. This law established a system of public schools,

provided for the organization of a board of education to direct the

educational affairs of the new province, provided for the election of

school trustees and defined their duties somewhat vaguely, and set apart

certain sums of public money for the partial support of the public

schools created by it.

The

act itself was somewhat simple, the Board of Education being empowered

to work out in detail the regulations necessary for the management of

the new schools. It was to determine courses of study, ln the

requirements for teachers' certificates, conduct the necessary

examinations, allot the government grants, etc. On June 21st a

proclamation of the lieutenant-governor appointed the following

gentlemen as a board of education: Rev. Alexandre Tache, Bishop of St.

Boniface, Rev. Joseph Lavoie, Rev.. Geo. Dugas, Rev. Joseph Allard, Hon.

Joseph Royal, Mr. Pierre Delorme, Mr. Joseph Dubuc, Rev. Robert Machray,

Bishop of Rupert's Land, Rev. George Young, Rev. John Black, Rev.

Cyprian Pinkhain. C. J. Bird, M. I)., Mr. John Norquay, Mr. Molvneaux

St. John. This board was to work in two sections, one having charge of

Roman Catholic schools, the other of Protestant schools. The first seven

members named above composed the Roman Catholic section, the others the

Protestant section. Mr. Royal was named as the superintendent of the

Catholic schools, and Mr. St. John of the Protestant schools. When the

board met for organization on June 30th, the Bishop of St. Boniface was

elected chairman of the Catholic section, and the Bishop of Rupert's

Land as presiding officer of the other section.

On

July 13th Governor Archibald announced by proclamation the boundaries of

the twenty-six school districts into which the settled portion of the

province had been divided. The Protestant districts, numbered from 1 to

16, were North St. Peter's, South St. Peter's, Mapleton, North St.

Andrew's, Central St. Andrew's, South St. Andrew's, St. Paul's, Kildonan,

St. John's, Winnipeg, St. James, Headingly. Poplar Point, High Bluff,

Portage, and Westbourne. There were ten Catholic districts, numbered

from 17 to 26 inclusive, whose boundaries were determined largely by

those of the electoral districts in which the majority of the people

were French. Most of them lay along the Red River between the

Assiniboine and the international boundary.

The

elections of school trustees took place on July 18th, but the people did

not take a very active interest in them. Some of the trustees elected

were: Hon. Colin Inkster, Mr. Magnus Brown, and Rev. Archdeacon McLean

in St. John's; Messrs. John Bourke, A. Fidler. and R. Tait in St. James;

Messrs, W. 'fait, J. Cunningham. M. P. P., and J. Taylor in Headingly;

Messrs. Chas. Thomas, Hugh Pritchard. and J. Clouston in St. Paul's; and

Messrs. Stewart Mulvey, W. G. Fonseca. and A. Wright in Winnipeg. In

most of the districts the electors decided to levy a tax for the support

of the schools; but in Winnipeg, although it then had a population of

about 700, the ratepayers decided to raise money for their school by a

subscription rather than a general tax. Of course this was only a

temporary arrangement.

The

first public schools opened on August 28, 1871. Some of the teachers

were to become prominent in the life of the province a little later. In

the East Kildonan school the teacher was Mr. Alexander Sutherland, who

afterwards entered the legal profession and still later became a member

of Premier Norquay's cabinet. In the West Kildonan school Mr. George F.

Munroe was in charge. He was afterwards a barrister and prominent in

municipal affairs. The Winnipeg school board was late in getting its

school organized, and it was not until October 3()th that the first

pupils assembled in the small log building on Point Douglas, which the

board had secured as a school. The young man behind the teacher's desk

that morning was Mr. W. F. Luxton, subsequently founder and editor of

the Manitoba Free

Press, member of the legislature, school

trustee, and member of the Board of Education.

The

new school act was not without its defects. Some people declared that

many of the public schools were inefficient, others were dissatisfied

with the regulations which governed the distribution of the provincial

grant. There was a feeling that the grants to individual schools should

be proportional to the number of pupils in attendance as well as the

time during which the school was kept open. It may have been this

feeling which led Hon. Mr. Davis, when he became premier in 1874, to

insert the following clause in his published policy: "The amendment of

the school laws, so as to secure an accurate list of the attendance of

pupils in the schools, duly verified under oath.

Dissatisfaction with the practical working of the Education Act of 1871

seems to have increased rather than diminished as the years went by, and

by 1876 there was a very general demand on the part of a large section

of the community for radical changes in the law. Those who were anxious

to make the schools more effective demanded the abolition of the board

of education and the creation of a department of education with a

cabinet minister at its head, the establishment of a purely

non-sectarian system of public schools, all subject to the same

regulations, the appointment of one or more inspectors, the early

establishment of a training school for teachers, and a complete change

in the method of dividing the provincial grant for the support of public

schools. Fourteen years were to pass, however, before the most important

of these changes were made, although others were brought about much

sooner.

The

act of 1871 had made no provision for secondary education, none for

university training. These departments of educational work were left,

for the time being, to the three denominational colleges, which had been

incorporated in 1871. These institutions, hampered as they were by lack

of funds, could hardly be expected to undertake the full work of a

university; and many public-spirited citizens looked forward to the time

when the province itself could undertake that work. It was an ambitious

project for a province so small in area and population and with such a

small revenue, and many friends of education feared that it would be

impossible to secure the co-operation of the different religious

denominations in any scheme for a provincial university.

Hon. Alexander Morris was very anxious to signalize his term as

lieutenant-governor of Manitoba by the establishment of a provincial

university, and he seems to have discussed the matter informally with

several leading men of the province. We are informed that he had urged

the members of the government to introduce a university bill into the

legislature; but they felt that the province was too weak financially to

undertake the establishment and support of such an institution. But

Governor Morris was too ardent a friend of education to relax his

efforts on behalf of a provincial university. On the evening of February

4, 1876, a public meeting was held in Winnipeg in connection with

Manitoba College. Two of the gentlemen who made addresses on that

occasion presented carefully considered schemes by which a provincial

university might be established at no great cost to the province and

with which the existing colleges could be affiliated. One of these

far-seeing, practical men was Mr. J. W. Taylor, the United States

consul, and the other was Rev. Dr. Robertson, superintendent of

Presbyterian missions in the west. Dr. Robertson's plan appealed to the

lieu tenant-governor, and it was not long before the two men met in

consultation over it. A detailed scheme was worked out, and a bill was

drawn up to embody it. There is good reason to believe that the governor

himself drafted the bill, and this may be one reason why the government

consented to introduce it.

The

third session of the second Manitoba legislature was opened on January

30, 1877. In the speech from the throne Lieutenant-Governor Morris said,

"In view of the necessity of affording the youth of the province the

advantages of higher education, a bill will be submitted to you,

providing for the establishment on a liberal basis of a university for

Manitoba, and for the affiliation there with of such of the existing

incorporated colleges as may take advantage of the university. Provision

will be made in the bill for the eventual establishment of a provincial

normal school for teachers. I regard this measure as one of great

importance, and as an evidence of the rapid progress of the country

towards the possession of so many of the advantages which the older

provinces of the Dominion already enjoy." Strictly speaking, the bill

was not a government measure, although Hon. Mr. Royal introduced it on

February 1st and moved its second reading eight days later. It received

a few amendments m committee, and on February 20th it passed its third

reading.

The

act provided for the establishment of a university which would outline

courses, conduct examinations, and grant degrees. It would not undertake

the work of teaching immediately, but professorships might be

established later so as to make the institution a teaching university.

The governing body, or council, was to consist of representatives of the

colleges which might affiliate with the university, a representative of

each section of the board of education, and a representative of the

graduates of other universities resident in the province. University

students were to be free from all religious tests, and in examinations

they might answer either in English or in French. The colleges retained

con trol of courses in theology and had power to grant theological

degrees, and they could select their own text-books in mental and moral

science. The financial burden, which some feared, was most carefully

avoided, inasmuch as one clause in the act limited the government grant

for university purposes to $250 per year. Of course this clause was soon

repealed.

St.

Boniface College, St. John's College, and Manitoba College affiliated

with the provincial university at once and elected their representatives

to the council; but Wesley College, which had been incorporated a few

days before the university bill passed the legislature, was not in a

position to affiliate then. At the first meeting of the university

council, held oil October 4, 1877, the Bishop of Rupert's Land was

chosen as chancellor, Hon. -Joseph Royal as vice-chancellor, Major

Jarvis as registrar, and Mr. I). MacArthur as bursar. A few days later

the first university students were enrolled, and on June 9, 1880, the

University of Manitoba conferred its first degrees.

About 1881 a Baptist college was organized at Rapid City by Rev, Dr.

Crawford, but it did not meet with the support expected and was closed

in 1883. A year or two later it was reopened in Brandon under the

direction of Rev. S. J McKee, D. I)., and received more generous support

from the denomination which it was established to serve. It has since

grown into a large institution, doing work in arts and theology and

furnishing a commercial training to those who desire it. It has never

affiliated with the provincial university; and although its friends have

asked the legislature to give it degree-conferring powers, the request

has not been granted.

In

1882 Manitoba Medical College was affiliated with the provincial

university, and six years later Wesley College was reorganized and

joined the sisterhood of affiliated institutions. The College of

Pharmacy was affiliated in 1902 and Manitoba Agricultural College in

1908, although the latter withdrew from the union in 1912 and became an

independent institution. The Law Society of Manitoba accepts

matriculation standing in the university as evidence of fitness to enter

upon the study of law, although it has not yet entrusted to the

university the work of examining candidates for admission to the bar,

and certain degrees in law are conferred by the university.

The

university council has not been a unit in regard to the lines on which

the institution should be developed, some members wishing it to remain

an examining and degree-conferring body, others desiring to make it a

teaching university. In 1886 the University Act was amended in such a

way that the university seemed debarred from assuming the work of

instruction; but a year later another amendment gave the graduates of

the university increased representation in the council, and most of the

new members joined the party which wished to make the university a

teaching institution. Circumstances combined to favor the policy of this

party. All over the continent there was a popular demand that the

natural sciences be given a larger place on college and university

curricula, and Manitoba's colleges were financially unable to meet this

demand. For a few years, commencing in 1890, they attempted to

co-operate in the teaching of science; but the plan was not

satisfactory, and in 1893 the University Act was amended once more to

permit the teaching of science and mathematics.

In

1878 the university applied to the Dominion for a grant of land as an

endowment, and this application was endorsed by the legislature a year

later. A grant of 150,000 acres was secured by the settlement made in

1885, although the patents to these lands were not secured until about

1898. The lands then became a source of a growing revenue to the

university. The other sources were the annual grant from the provincial

government and the income from a considerable bequest received some

years before from the estate of A. K. Isbister, the gentleman who was

the champion of the Red River people in their struggle; against the

monopoly of the Hudson's Bay Company in the pre-confederation years.

Under the circumstances the university council felt justified in

erecting a building. The Old Driving Park was secured from the Dominion

government as a site, and the first university building was erected on

it m 1900. A further extension of university teaching took place in

1904, and three years later the council decided that the university

should aim to give instruction in all branches of higher education. In

conformity with this policy a department of engineering was organized,

and its field has been widened as fast as the finances of the university

will permit.

The

fact that the University of Manitoba had been transformed into a

teaching institution gave increased strength to an agitation in favor of

making it a provincial university in every respect. In 1908 the

provincial government-appointed a commission to investigate the

educational needs and conditions of Manitoba, study the character of

university work done elsewhere, and make recommendations

in regard to the future policy and management

of the University of Manitoba. Unfortunately the members of the

commission could not agree, and the government received several reports

from the sections into which it divided. As a result the questions of

site, future policy, and control remained in suspense for several years.

A president for the university was chosen in 1912, and it is hoped that

he will lead the institution out of the wilderness.

An

amendment to the school law, passed in 1879, fixed the number of members

in the Protestant section of the board of education at twelve and the

members of the Catholic section at nine, provided for the appointment of

inspectors, and defined their duties. The government grant in aid of

schools was increased about the same time. Previous to 1881 the

government had made no provision for secondary education, but in that

year an amendment to the School Act remedied the defect. The Winnipeg

school board promptly took advantage of the amendment, and in the summer

of 1882 it established a high school, calling it a collegiate

department. A collegiate department was organized m Brandon a year

later', and in a short time a similar secondary school was established

at Portage la Prairie. A few years later schools, known as intermediate

schools, were established in several of the smaller towns for the

purpose of providing a certain amount of secondary education; and still

later a number of larger and better equipped secondary schools, called

high schools, were organized.

In

1882 a normal school department was opened in connection with the

schools of "Winnipeg, its first principal being Mr. E. L. Byington, and

ir a few years it developed into an independent provincial normal

school, to which a model school was subsequently attached. There are

also normal schools for the training of third class teachers at Brandon,

Dauphin, Portage la Prairie, and Manitou; the French teachers receive

their professional training at a normal school in St. Boniface; there is

a training school for Mennonite teachers at Gretna, one for Ruthenian

teachers at Brandon, and one for Polish teachers in Winnipeg.

The

story of the dissatisfaction with the School Act of 1871, which resulted

in its repeal during 1890, has been told in a previous chapter. Most of

the changes made by the new law had been favored by Mr. Norquav; but he

hoped that they could be made gradually and with little friction between

Roman Catholics and the remainder of the community, and during his

premiership the time did not seem ripe for legislation in the matter.

One clause of the repealed act provided a compulsory attendance law for

any school district which wished to adopt it; but this clause did not

find a place in the new act of 1890. Since that time there has been a

strong conviction in the minds of many friends of education that a

compulsory school Law for the province should be enacted, and this

conviction is strengthened by a knowledge of the conditions and problems

which are growing out of the great increase in Manitoba's foreign-born

population.

Commercial education has never been neglected in Manitoba. The first

commercial college of Winnipeg was opened in September, 1876, and since

that time many similar schools have been established with varying

success in "Winnipeg and other towns of the province. In 1896 the school

board of "Winnipeg made a commercial course a part of the curriculum in

its collegiate institute, and similar courses of instruction are now

provided in the other collegiate institutes of^ the province.

Through the generosity of Sir William Macdonald manual training was

introduced into the schools of Winnipeg in the latter part of 1900. Sir

William supplied the necessary equipment and paid the salaries of

instructors for three years, and at the end of that period the school

board, thoroughly convinced of the value of the work, made it a regular

part of the school course. About the same time it arranged to give the

girls in its schools instruction in needlework, cookery, and other

domestic arts. The movement spread, and in most of the towns and in some

of the rural districts manual training and domestic science now find

places in the school programmes. Quite recently steps have been taken to

make technical training a part of the work done in the public schools.

The government took the matter up and appointed a commission on

technical education in 1910; but without waiting for the report of the

commission or for the formulation of a definite policy on the matter by

the department of education, the Winnipeg school board decided to

undertake technical education, and in 1912 two large and completely

equipped technical high schools were opened in the city.

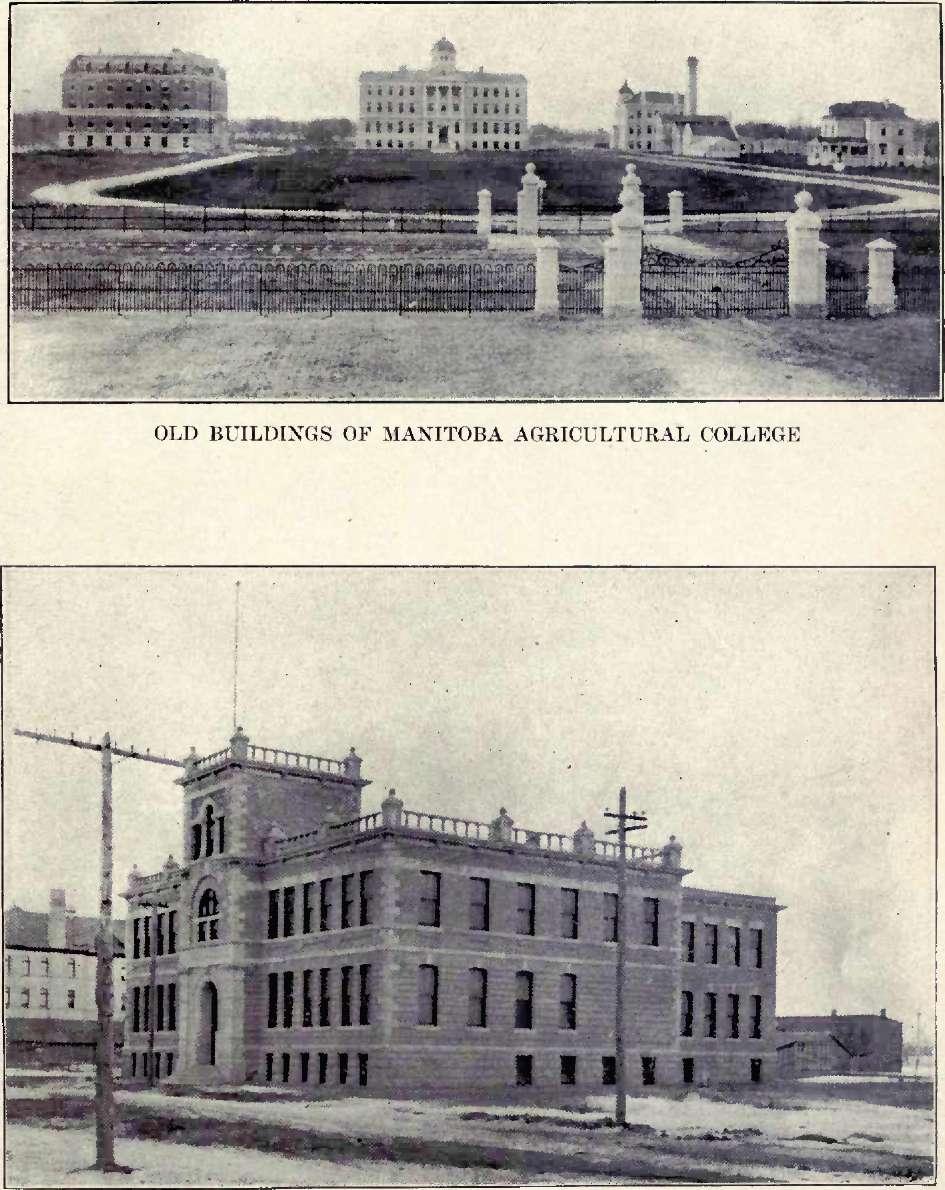

As

agriculture must always be the leading industry of the province, the

government recognized the importance of providing for all who wish it

instruction in the scientific principles which underlie successful

methods of farming, as well as some practical training in farm work. A

farm was secured on the south side of the Assiniboine River a short

distance west of the limits of the city of Winnipeg, suitable buildings

were erected upon it, machinery and stock were provided, a staff of

instructors engaged, and on November 6, 1906, the Manitoba Agricultural

College was opened. There were 68 students in attendance and

applications from 90 more had been received. Within a few years the

college was affiliated with the provincial university, and special

courses were arranged for students who wished to take the degree of

bachelor of scientific agriculture. The value of the college was soon

recognized, and the attendance increased beyond the capacity of the

buildings. A larger site was secured on the west bank of the Red River,

and on it a number of commodious and well-designed buildings are being

erected. When they are completed, the institution will be moved into

them, and Manitoba will then have one of the most complete agricultural

colleges in Canada. |