|

THE last passenger had

taken his seat, the last trunk been strapped on behind, and the canvas

covering drawn tightly over it, the mail bags safely stowed away in the

capacious boot; and then big Jack Davis, gathering the reins of his six

impatient steeds skilfully into one hand, and grasping the long-lashed

whip in the other, sang out to the men who stood at the leaders’ heads:

“Let them go!”

The men dropped the bridles and sprang aside, the long lash cracked like

a pistol shot, the leaders, a beautiful pair of grey ponies, perfectly

matched, reared, curvetted, pranced about, and then would have dashed

off at a wild gallop had not Jack Davis’ strong hands, aided by the

steadiness of the staider wheelers, kept them in check: and soon brought

down to a spirited canter, they led the way out of the town.

The coach had a heavy load. It could hold twelve passengers inside, and

every seat was occupied on top. Besides Mr. Miller, who had the coveted

box seat, there were two other men perched upon the coach top, and

making the best of their uncomfortable position; and there was an extra

amount of baggage.

“Plenty of work for my horses to-day, Mr. Miller,” said Jack Davis,

looking carefully over the harnessing to make sure that every strap was

securely buckled, and every part in its right place.

“Yes, indeed; you’ll need to keep the brake on hard going down the

hills,” replied Mr. Miller.

Bending over, so that those behind could not hear him, the driver said,

under his breath:

“Don’t say anything; but, to tell the truth, I’m a little shaky about my

brake. It is none too strong, and I won’t go out with it again until

it’s fixed; but it can’t be mended this side of Riverton, and I’m going

to push through as best I can.”

“Well, if anything happens, just let us know when to jump,” returned Mr.

Miller, with a reassuring smile, for he felt no anxiety, having perfect

confidence in Davis’ ability to bring his coach safely to the journey’s

end.

It was a lovely summer day, and in the early afternoon the coach bowled

smoothly along over the well-kept road, now rolling over a wooden bridge

on whose timbers the rapid tramp of the horses’ feet sounded like

thunder, climbing the slope on the other side, then rattling down into

the valley, and up the opposite hill, almost at full speed, and so on in

rapid succession. Bert, kneeling at the window, with arms resting on the

ledge, and just able to see the three horses on his side, was so

engrossed in watching them, or peering into the forest through which the

road cut its way, that he quite forgot his desire to be up on top of the

coach.

Having gone fifteen miles at a spanking pace, the coach drove into a

long-covered barn for the horses to be changed, and everybody got out to

stretch their legs; while this was being done, Berts longing came back

in full force. As he stood watching the tired foam-flecked horses being

led away, and others, sleek, shining, and spirited put in their places,

who should pass by but Mr. Miller. Recognising at once his little

acquaintance of the morning, he greeted him with a cheery:

“Hallo! my little man, are we fellow-travellers still? And how do you

like riding in a coach?”

“I think it’s just splendid, sir,” replied Bert; and then, as a bright

thought flashed into his mind,—“but I do so want to be up where the

driver is.”

Mr. Miller looked down at the little face turned up to his, and noting

its eager expression asked, kindly:

“Do you think your mother would let you go up there?”

“Oh, yes; she said I might if I would only wait a little, and it is a

good deal more than a little while now.”

“Very well, Bert, you run and ask her if you may get up now, and I'll

try and manage it,” said Mr. Miller.

Bert was not long in getting his mother’s sanction, and when he returned

with beaming face, Mr. Miller taking him up to Jack Davis, said:

“Jack, this little chap is dying to sit up with us. He wants to see how

the best driver in Acadia handles his horses, I suppose.”

There was no resisting such an appeal as this. Tickled with the

compliment, Jack said, graciously:

“All right, Mr. Miller, you can chuck him up, so long as you’ll look

after him yourself.”

And so when the fresh horses were harnessed, and the passengers back in

their places, behold Cuthbert Lloyd, the proudest, happiest boy in all

the land, perched up between the driver and Mr. Miller, feeling himself

as much monarch of all he surveyed, as ever did Robinson Crusoe in his

island home. It was little wonder if for the first mile or two he was

too happy to ask any questions. It was quite enough from his lofty, but

secure position, to watch the movements of the six handsome horses

beneath him as, tossing their heads, and making feigned nips at one

another, they trotted along with the heavy coach as though it were a

mere trifle. The road ran through a very pretty district;

well-cultivated farms, making frequent gaps in the forest, and many a

brook and river lending variety to the scene. After Bert had grown

accustomed to the novelty of his position, his tongue began to wag

again, and his bright, innocent questions afforded Mr. Miller so much

amusement, that with Jack Davis’ full approval, he was invited to remain

during the next stage also. Mrs. Lloyd would rather have had him with

her inside, but he pleaded so earnestly, and Mr. Miller assuring her

that he was not the ‘least trouble, she finally consented to his staying

up until they changed horses again.

When they were changing horses at this post, Mr. Miller drew Bert’s

attention to a powerful black horse one of the men was carefully leading

out of the stable. All the other horses came from their stalls fully

harnessed, but this one had on nothing except a bridle.

“See how that horse carries on, Bert,” said Mr. Miller.

And, sure enough, the big brute was prancing about with ears bent back

and teeth showing in a most threatening fashion.

“They daren’t harness that horse until he is in his place beside the

pole, Bert. See, now, they ’re going to put the harness on him.”

And as he spoke another stable hand came up, deftly threw the heavy

harness over the horse’s back, and set to work to buckle it with a speed

that showed it was a job he did not care to dally over. No sooner was it

accomplished than the other horses were hastily put in their places, the

black wheeler in the meantime tramping upon the barn floor in a seeming

frenzy of impatience, although his head was tightly held.

“Now, then, ‘all aboard’ as quick as you can,” shouted Jack Davis,

swinging himself into his seat. Mr. Miller handed up Bert and followed

himself, the inside passengers scrambled hurriedly in, and then with a

sharp whinny the black wheeler, his head being released, started off,

almost pulling the whole load himself.

“Black Rory does not seem to get over his bad habits, Jack,” remarked

Mr. Miller.

“No,” replied Jack; “quite the other way. He’s getting worse, if

anything; but he’s too good a horse to chuck over. There’s not a better

wheeler on the route than Rory, once he settles down to his work.”

After going a couple of miles, during which Rory behaved about as badly

as a wheeler could, he did settle down quietly to his work and all went

smoothly. They were among the hills now, and the steep ascents and

descents, sharp turns, and many bridges over the gullies made it

necessary for Davis to drive with the utmost care. At length they

reached the summit of the long slope, and began the descent into the

valley.

“I’d just as soon I hadn’t any doubts about this brake,” said Davis to

Mr. Miller, as he put his foot hard down upon it.

“Oh, it’ll hold all right enough, Jack,” replied Mr. Miller,

reassuringly.

“Hope so,” said Davis. “If it doesn’t, we’ll have to run for it to the

bottom.”

The road slanted steadily downward, and with brake held hard and

wheelers spread out from the pole holding back with all their strength,

the heavy coach lumbered cautiously down. Now it was that Black Rory

proved his worth, for, thoroughly understanding what was needed of him,

he threw his whole weight and strength back upon the pole, keeping his

own mate no less than the leaders in check.

“We’ll be at Brown’s Gully in a couple of minutes,” said the driver.

“Once we get past there, all right; the rest won’t matter.”

Brown’s Gully was the ugliest bit of road on the whole route, A steep

hill, along the side of which the road wound at a sharp slant, led down

to a deep, dark gully crossed by a high trestle bridge. Just before the

bridge there was a sudden turn which required no common skill to safely

round when going at speed.

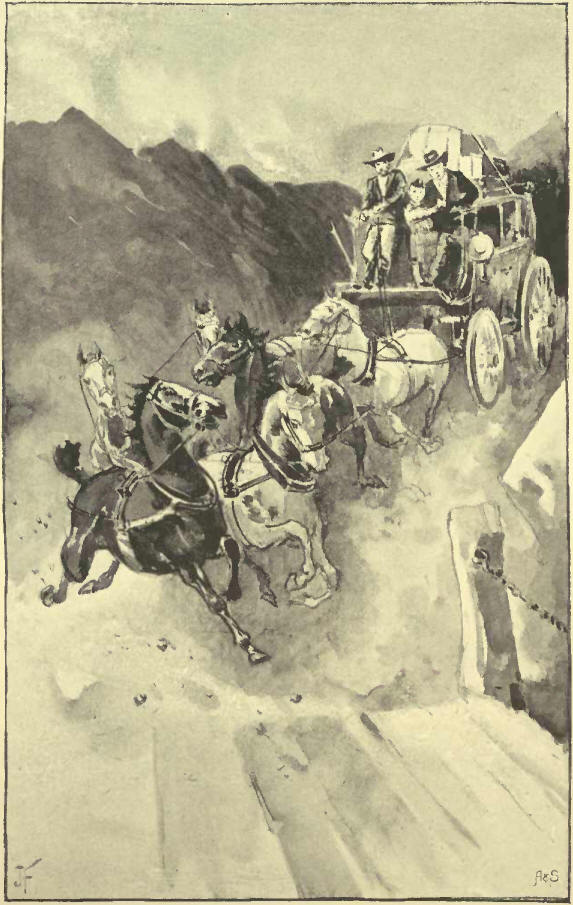

As they reached the beginning of the slant, Jack Davis’ face took on an

anxious look, his mouth became firm and set, his hand tightened upon the

reins, and his foot upon the brake, and with constant exclamation to his

horses of “Easy now!—go easy!—hold back, my beauties!” he guided the

great coach in its descent.

Mr. Miller put Bert between his knees, saying:

“Stick right there, my boy; don’t budge an inch.” Although the wheelers,

and particularly Black Rory, were doing their best, the coach began to

go faster than Davis liked, and with a shout of “Whoa there! Go easy,

will you!” he had just shoved his foot still harder against the brake,

when there was a sharp crack, and the huge vehicle suddenly sprang

forward upon the wheelers’ heels.

“God help us!” cried Jack, “the brake’s gone. We’ve got to run for it

now.”

And run for it they did.

It was a time of great peril. Mr. Miller

clung tightly to the seat, and Bert shrank back between his knees.

Davis, with feet braced against the dashboard, and reins gathered close

in his hands, put forth all his great strength to control the horses,

now flying over the narrow road at a wild gallop. Brown’s Gully, already

sombre with the shadows of evening, showed dark and deep before them.

Just around that corner was the bridge. Were they to meet another

carriage there, it would mean destruction to both. Davis well knew this,

and gave a gasp of relief when they swung round the corner and saw that

the road was clear. If they could only hit the bridge, all right; the

danger would be passed.

“Now, Rory, now,” shouted Davis, giving a tremendous tug at the horse’s

left rein, and leaning far over in that direction himself.

“Davis put forth all his strength to control the horses, now Hying over

the road at a wild gallop. ”

Mr. Miller shut his eyes; the peril seemed too great to be gazed upon.

If they missed the bridge, they must go headlong into the gully. Another

moment and it was all over.

As the coach swung round the corner into the straight road beyond, its

impetus carried it almost over the edge, but not quite. With a splendid

effort, the great black wheeler drew it over to the left. The front

wheels kept the track, and although the hind wheels struck the side rail

of the bridge with a crash and a jerk that well-nigh hurled Bert out

upon the horses’ backs, and the big coach leaned far over to the right,

it shot back into the road again, and went thundering over the trembling

bridge uninjured.

“Thank God!” exclaimed Mr. Miller, fervently, when the danger was

passed.

“Amen!” responded Jack Davis.

“I knew He would help us,” added Bert.

“Knew who would, Bert?” inquired Mr. Miller, bending over him tenderly,

while something very like a tear glistened in his eye.

“I knew God would take care of us,” replied Bert, promptly. “The driver

asked Him to; and didn’t you ask Him, too?”

“I did,” said Mr. Miller, adding, with a sigh, “but I’m afraid I had not

much right to expect Him to hear me.”

They had no further difficulties. The road ran smoothly along the rest

of the way, and shortly after sundown the coach, with great noise and

clatter, drove into the village of Riverton, where grandpapa was to meet

Mrs. Lloyd and Bert, and take them home in his own carriage. |