|

THE summer days passed

very quickly and happily for Bert at Maplebank, especially after the

surprising revelation of the love and tenderness that underlay his

grandfather’s stern exterior. No one did more for his comfort or

happiness than his grandmother, and he loved her accordingly with the

whole strength of his young heart. She was so slight and frail, and

walked with such slow, gentle steps, that the thought of being her

protector and helper often came into his mind and caused him to put on a

more erect, important bearing as he walked beside her in the garden, or

through the orchard where the apples were already beginning to give

promise of the coming ripeness.

Mrs. Stewart manifested her love for her grandson in one way that made a

great impression upon Bert. She would take him over to the dairy, in its

cool place beneath the trees, and, selecting the cooler with the

thickest cream upon it, would skim off a teaspoonful into a large spoon

that was already half filled with new oatmeal, and then pour the

luscious mixture into the open mouth waiting expectantly beside her.

“Is not that fine, Bertie boy?” she would say, patting him

affectionately upon the head; and Bert, his mouth literally too full for

utterance, would try to look the thanks he could not speak.

Maplebank had many strange visitors. It stood a little way back from the

junction of three roads, and the Squire’s hospitality to wayfarers being

unbounded, the consequence was that rarely did a night pass without one

or more finding a bed in some corner of the kitchen. Sometimes it would

be a shipwrecked sailor, slowly finding his way on foot to the nearest

shipping port. Sometimes a young lad with pack on back, setting out to

seek his fortune at the capital, or in the States beyond. Again it would

be a travelling tinker, or tailor, or cobbler, plying his trade from

house to house, and thereby making an honest living.

But the most frequent visitors of all—real nuisances, though, they often

made themselves—were the poor, simple folk, of whom a number of both

sexes roamed ceaselessly about. Not far from Maplebank was what the

better class called a “straglash district”— that is, a settlement

composed of a number of people who had by constant intermarriage, and

poor living, caused insanity of a mild type to be woefully common.

Almost every family had its idiot boy or girl, and these poor creatures,

being, as a rule, perfectly harmless, were suffered to go at large, and

were generally well treated by the neighbours, upon whose kindness they

were continually trespassing.

The best known of them at the time of Bert’s visit, was one called

“Crazy Colin,” a strange being, half wild, half civilised, with the

frame of an athlete, and the mind of a child. Although more than thirty

years of age, he had never shown much more sense than a two-year-old

baby. He even talked in a queer gibberish, such as was suitable to that

stage of childhood. Everybody was kind to him. His clothes and his food

were given him. As for a roof, he needed none in summer save when it

stormed, and in winter he found refuge among his own people. His chief

delight was roaming the woods and fields, talking vigorously to himself

in his own language, and waving a long ash staff that was rarely out of

his hands. He would thus spend whole days in apparent content, returning

only when the pangs of hunger could be borne no longer.

Bert took a great deal of interest in these “strag-lash” people, and

especially in Crazy Colin, who was a frequent visitor at the Squire’s

kitchen, for Mrs. Stewart never refused him a generous bowl of porridge

and milk, or a huge slice of bread and butter. At first he was not a

little afraid of Crazy Colin. But soon he got accustomed to him, and

then, boy-like, presuming upon acquaintance, began to tease him a bit

when he would come in for a “bite and sup.” More than once the idiot’s

eyes flashed dangerously at Bert’s pranks ; but, fool though he was, he

had sense enough to understand that any outbreak would mean his prompt

expulsion and banishment, and so he would restrain himself. One

memorable day, however, when Bert least expected or invited it, the

demon of insanity broke loose in a manner that might have had serious

consequences.

It was on a Sunday. The whole family had gone off to church, except

Bert, who had been left at home in the charge of the cook. She was a

strapping big Scotch lassie, and very fond of Bert. About an hour after

the family left, Crazy Colin sauntered along and took his seat in the

kitchen. Neither Kitty nor Bert was by any means pleased to see him, but

they thought it better to keep their feelings to themselves. Bert,

indeed, made some effort to be entertaining, but Crazy Colin seemed in

rather a sulky mood, an unusual thing for him, so Bert soon gave it up,

and went off into the garden.

The roses were blooming beautifully there, and he picked several before

returning to the kitchen. When he came back, he found the unwelcome

visitor alone, Kitty having gone into the other part of the house. He

was sitting beside the table with his head bent forward upon his hands,

apparently in deep dejection. Upon the table was a large knife which

Kitty had just been using in preparing the meat for dinner. Thinking it

would please poor Colin, Bert selected the finest rose in his bunch and

handed it to him, moving off toward the door leading into the hall as he

did so. Colin lifted his head and grasped the rose rudely. As his big

hand closed upon it, a thorn that hid under the white petals pierced

deep into the ball of his thumb. In an instant the sleeping demon of

insanity awoke. With eyes blazing and frame trembling with fury, he

sprang to his feet, seized the knife, and with a hoarse, inarticulate

shout, turned upon Bert, who, paralysed with terror, stood rooted to the

spot half-way between the idiot and the door. It was a moment of

imminent peril, but ere Crazy Colin could reach the boy, his hoarse cry

was echoed by a shrill shriek from behind Bert, and two stout arms

encircling him, bore him off through the door and up the stairs, pausing

not until Squire Stewart’s bedroom was gained and the door locked fast.

Then depositing her burden upon the floor, brave, big Kitty threw

herself into a chair, exclaiming, breathlessly:

“Thank God, Master Bert, we’re safe now. The creature darsen’t come up

those stairs.”

And Kitty was right; for although Crazy Colin raged and stormed up and

down the hall, striking the wall with the knife, and talking in his

wild, unintelligible way, he did not attempt to set foot upon the

stairs. Presently he became perfectly quiet.

“Has he gone away, Kitty?” asked Bert, eagerly, speaking for the first

time. “He’s not making any noise now.”

Kitty stepped softly to the door, and putting her ear to the crack,

listened intently for a minute.

“There’s not a sound of him, Master Bert. Please God, he’s gone, but we

hadn’t better go out of the room until the folks come home. He may be

waiting in the kitchen.”

And so they stayed, keeping one another company through the long hours

of the morning and afternoon until at last the welcome sound of wheels

crushing the gravel told that the carriage had returned, and they might

leave their refuge.

The indignation of Squire Stewart when he heard what had occurred was a

sight to behold. Sunday though it was, be burst forth into an

unrestrained display of his wrath, and had the cause of it ventured

along at the time, he certainly would have been in danger of bodily

injury.

“The miserable trash!” stormed the Squire. “Not one of them shall ever

darken my threshold again. Hech! that’s what comes of being kind to such

objects. They take you to be as big fools as themselves, and act

accordingly. The constable shall lay his grip on that loon so sure as I

am a Stewart.” There were more reasons for the Squire’s wrath, too, than

the fright Crazy Colin had given Bert and Kitty, for no dinner awaited

the hungry church-goers, and rejoiced as they all were at the happy

escape of the two who had been left at home, that was in itself an

insufficient substitute for a warm, well-cooked dinner. But Kitty, of

course, could not be blamed, and there was nothing to be done but to

make the best of the situation, and satisfy their hunger upon such odds

and ends as the larder afforded.

As for poor Crazy Colin, whether by some subtle instinct on coming to

himself he realised how gravely he had offended, or whether in some way

or other he got a hint of the Squire’s threats, cannot be said. Certain

it was, that he did not present himself at Maplebank for many days

after, and then he came under circumstances, which not only secured him

complete forgiveness, but made him an actual hero, for the time, and won

him a big place in the hearts of both Bert and his mother.

Although Bert had been forbidden to leave the homestead, unless in

company with some grown-up person, he had on several occasions forgotten

this injunction, in the ardour of his play, but never so completely as

on the day that, tempted by Charlie Chisholm, the most reckless, daring

youngster in the neighbourhood, he went away off into the back-lands, as

the woods beyond the hill pasture were called, in search of an eagle’s

nest, which the unveracious Charlie assured him was to be seen high up

in a certain dead monarch of the forest.

It was a beautiful afternoon, toward the end of August, when Bert, his

imagination fired by the thought of obtaining a young eagle, Charlie

having assured him that this was entirely possible, broke through all

restraints, and went off with his tempter. Unseen by any of the

household, as it happened, they passed through the milk yard, climbed

the hill, hastened across the pasture, dotted with the feeding cows, and

soon were lost to sight in the woods that fringed the line of settlement

on both sides of the valley, and farther on widened into the great

forest that was traversed only by the woodsman and the hunter.

On and on they went, until at length Bert was tired out. “Aren’t we far

enough now, Charlie?” he asked, plaintively, throwing himself down upon

a fallen tree to rest a little.

“Not quite, Bert; but we’ll soon be,” answered Charlie. “Let’s take a

rest, and then go ahead,” he added, following Bert’s example.

Having rested a few minutes, Charlie sprang up saying:

“Come along, Bert; or we’ll never get there.” And somewhat reluctantly

the latter obeyed. Deeper and deeper into the forest they made their

way, Charlie going ahead confidently, and Bert following doubtfully; for

he was already beginning to repent of his rashness, and wish that he was

home again.

Presently Charlie showed signs of being uncertain as to the right route.

He would turn first to the right and then to the left, peering eagerly

ahead, as if hoping to come upon the big dead tree at any moment.

Finally he stopped altogether.

“See here, Bert; I guess we ’re on the wrong track,” said he, coolly.

“I’ve missed the tree somehow, and it’s getting late, so we’d better

make for home. We’ll have a try some other day.”

Poor little Bert, by this time thoroughly weary, was only too glad to

turn homeward, and the relief at doing this gave him new strength for a

while. But it did not last very long, and soon, footsore and exhausted,

he dropped down upon a bank of moss, and burst into tears.

“Oh, Charlie, I wish we were home,” he sobbed. “I’m so tired, and

hungry, too.”

Charlie did not know just what to do. It was getting on toward sundown;

he had quite lost his way, and might be a good while finding it again,

and he felt pretty well tired himself. But he put on a brave face and

tried to be very cheerful, as he said:

“Don’t cry, Bert. Cheer up, my boy, and we’ll soon get home.”

It was all very well to say “cheer up,” but it was another thing to do

it. As for getting home soon, if there were no other way for Bert to get

home than by walking the whole way, there was little chance of his

sleeping in his own bed that night.

How thoroughly miserable he did feel! His conscience, his legs, and his

stomach, were all paining him at once. He bitterly repented of his

disobedience, and vowed he would never err in the same way again. But

that, while it was all very right and proper, did not help him homeward.

At length Charlie grew desperate. He had no idea of spending the night

in the woods if he could possibly help it, so he proposed a plan to

Bert:

“See here, Bert,” said he, “you’re too played out to walk any more. Now,

I’ll tell you what I’ll do. I’ll run home as fast as I can, and saddle

the old mare and bring her here, and then we’ll ride back again

together. What do you say?”

“Oh, don’t leave me here alone?” pleaded Bert. “I’ll be awfully

frightened.”

“Chut! Bert. There’s nothing to frighten you but some old crows. Stay

just where you are, and I’ll be back inside of an hour.” And without

waiting to argue the point, Charlie dashed off into the woods in the

direction he thought nearest home; while Bert, after crying out in vain

for him to come back, buried his face in the moss and gave himself up to

tears.

One hour, two hours, three hours passed, and still Bert was alone. The

sun had set, the gloaming well-nigh passed, and the shadows of night

drew near. All kinds of queer noises fell upon his ear, filling him with

acute terror. He dared not move from the spot upon which Charlie had

left him, but sat there, crouched up close against a tree, trembling

with fear in every nerve. At intervals he would break out into vehement

crying, and then he would be silent again. Presently the darkness

enveloped him, and still no succour came.

Meantime, there had been much anxiety at Maplebank. On Bert’s being

missed, diligent inquiry was made as to his whereabouts, and at length,

after much questioning, some one was found who had seen him, in company

with Charlie Chisholm, going up through the hill pasture toward the

woods. When Mrs. Lloyd heard who his companion was, her anxiety

increased, for she well knew what a reckless, adventurous little fellow

Charlie was, and she determined that search should be made for the boys

at once. But in this she was delayed by Uncle Alec and the men being off

at a distance, and not returning until supper time. So soon as they did

get back, and heard of Bert’s disappearance, they swallowed their

supper, and all started without delay to hunt him up.

The dusk had come before the men—headed by Uncle Alec, and followed, as

far as the foot of the hill, by the old Squire—got well started on their

search; but they were half-a-dozen in number, and all knew the country

pretty well, so that the prospect of their finding the lost boy soon

seemed bright enough.

Yet the dusk deepened into darkness, and hour after hour passed—hours of

intense anxiety and earnest prayer on the part of the mother and others

at Maplebank—without any token of success.

Mrs. Lloyd was not naturally a nervous woman, but who could blame her if

her feelings refused control when her darling boy was thus exposed to

dangers, the extent of which none could tell.

The Squire did his best to cheer her in his bluff, blunt way:

“Tut! tut! Kate. Don’t worry so. The child’s just fallen asleep

somewhere. He’ll be found as soon as it’s light. There’s nothing to harm

him in those woods.”

Mrs. Lloyd tried hard to persuade herself that there wasn’t, but all

kinds of vague terrors filled her mind, and refused to be allayed.

At length, as it drew toward midnight, a step was heard approaching, and

the anxious watchers rushed eagerly to the door, hoping for good news.

But it was only one of the men, returning according to arrangement to

see if Bert had been found, and if not to set forth again along some new

line of search. After a little interval another came, and then another,

until all had returned, Uncle Alec being the last, and still no news of

Bert.

They were bidden to take some rest and refreshment before going back

into the woods. While they were sitting in the kitchen, Uncle Alec, who

was exceedingly fond of Bert, and felt more concerned about him than he

cared to show, having no appetite for food, went off toward the red gate

with no definite purpose except that he could not keep still.

Presently the still midnight air was startled with a joyful “Hurrah!”

followed close by a shout of “Bert’s all right—he’s here,” that brought

the people in the house tumbling pell-mell against each other in their

haste to reach the door and see what it all meant.

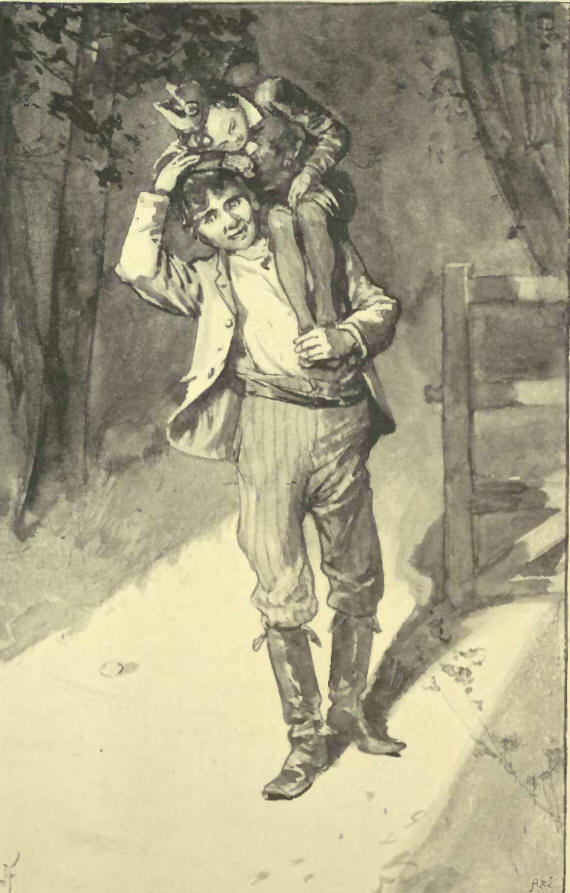

Crazy Colin strode up the road, bearing

Bert high upon his shoulder

The light from the

kitchen streamed out upon the road, making a broad luminous path, up

which the next moment strode Crazy Colin, bearing Bert high upon his

broad shoulders, while his swarthy countenance fairly shone with a smile

of pride and satisfaction that clearly showed he did not need Uncle

Alec’s enthusiastic clappings on the back, and hearty “Well done, Colin!

You’re a trump!” to make him understand the importance of what he had

done.

The two were at once surrounded by the overjoyed family. After giving

her darling one passionate hug, Mrs. Lloyd took both of Crazy Colin’s

hands in hers, and, looking up into his beaming face, said, with a deep

sincerity even his dull brain could not fail to appreciate: “God bless

you, Colin. I cannot thank you enough, but I’ll be your friend for

life;” while the Squire, having blown his nose very vigorously on his

red silk handkerchief, grasped Colin by the arm, dragged him into the

house, and ordered that the best the larder could produce should be

placed before him at once. It was a happy scene, and no one enjoyed it

more than did Crazy Colin himself.

The exact details of the rescue of Bert were never fully ascertained;

for, of course, poor Colin could not make them known, his range of

expression being limited to his mere personal wants, and Bert himself

being able to tell no more than that while lying at the foot of the

tree, and crying pretty vigorously, he heard a rustling among the trees

that sent a chill of terror through him, and then the sound of Crazy

Colins talk with himself, which he recognised instantly. Forgetting all

about the fright Colin had given him a few days before, he shouted out

his name. Colin came to him at once, and seeming to understand the

situation at a glance, picked him up in his strong arms, flung him over

his shoulder, and strode off toward Maplebank with him as though he were

a mere feather-weight and not a sturdy boy. Dark as it was, Colin never

hesitated, nor paused, except now and then to rest a moment, until he

reached the red gate where Uncle Alec met him, and welcomed him so

warmly.

Mrs. Lloyd did not think it wise nor necessary to say very much to Bert

about his disobedience. If ever there was a contrite, humbled boy, it

was he. He had learned a lesson that he would be long in forgetting. As

for his tempter, Charlie Chisholm, he did not turn up until the next

morning, having lost himself completely in his endeavour to get home;

and it was only after many hours of wandering he found his way to an

outlying cabin of the backwoods settlement, where he was given shelter

for the night. |