|

IT was an article of

faith in the Lloyd family that there was not a house in Halifax having a

pleasanter situation than theirs, and they certainly had very good

grounds for their belief. Something has already been told about its

splendid view of the broad harbour, furrowed with white-capped waves,

when of an afternoon the breeze blew in smartly from the great ocean

beyond; of its snug security from northern blasts; of the cosy nook it

had to itself in a quiet street; and of its ample exposure to the

sunshine. But, perhaps, the chief charm of all was the old fort whose

grass-grown casemates came so close to the foot of the garden, that ever

since Bert was big enough to jump, he had cherished a wild ambition to

leap from the top of the garden fence to the level top of the nearest

casemate.

This old fort, with its long, obsolete, muzzle-loading thirty-two

pounders, was associated with Bert’s earliest recollection. His nurse

had carried him there to play about in the long, rank grass underneath

the shade of the wide-spreading willows that crested the seaward slope

before he was able to walk; and ever since, summer and winter, he had

found it his favourite playground.

The cannons were an unfailing source of delight to him. Mounted high

upon their cumbrous carriages, with little pyramids of round iron balls

that would never have any other use than that of ornament lying beside

them, they made famous playthings. He delighted in clambering up and

sitting astride their smooth, round bodies as though they were horses;

or in peering into the mysterious depths of their muzzles. Indeed, once

when he was about five years old he did more than peer in. He tried to

crawl in, and thereby ran some risk of injury.

He had been playing ball with some of the soldier’s children, and seemed

so engrossed in the amusement that his mother, who had taken him into

the fort, thought he might very well be left for a while, and so she

went off some little distance to rest in quiet, in a shady corner. She

had not been there more than a quarter of an hour, when she was startled

by the cries of the children, who seemed much alarmed over something;

and hastening back to where she had left Bert, she beheld a sight that

would have been most ludicrous if it had not been so terrifying.

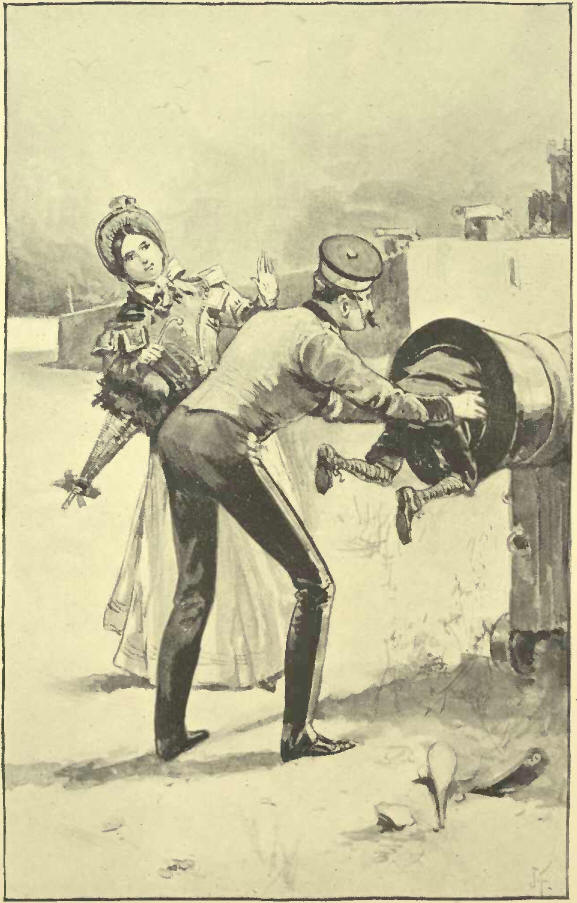

Protruding from the mouth of one of the cannons, and kicking very

vigorously, were two sturdy, mottled legs that she instantly recognised

as belonging to her son, while from the interior came strange muffled

sounds that showed the poor little fellow was screaming in dire

affright, as well he might in so distressing a situation. Too young to

be of any help, Bert’s playmates were gathered about him crying lustily,

only one of them having had the sense to run off to the carpenter’s shop

near by to secure assistance.

“Fortunately, a big soldier came along, and, slipping both hands as far

up on Bert’s body as he could reach, with a strong, steady pull drew him

out of the cannon.”

Mrs. Lloyd at once

grasped Bert’s feet and strove to pull him out, but found it no easy

matter. In his efforts to free himself he had only stuck the more

firmly, and was now too securely fastened for Mrs. Lloyd to extricate

him. Fortunately, however, a big soldier came along at this juncture,

and, slipping both hands as far up on Bert’s body as he could reach,

grasped him firmly, and with one strong, steady pull, drew him out of

the cannon.

When he got him out, Bert presented so comical a spectacle that his

stalwart rescuer had to lay him down and laugh until the tears rolled

down his cheeks. Mrs. Lloyd, too, relieved from all anxiety, and feeling

a reaction from her first fright, could not help following his example.

His face, black with grime, which was furrowed with tears, his hands

even blacker, his nice clothes smutched and soiled, and indeed, his

whole appearance suggested a little chimney-sweep that had forgotten to

put on his working clothes before going to business. Bert certainly was

enough to make even the gravest laugh.

Beyond a bruise or two, he was, however, not a whit the worse for his

curious experience, which had come about in this way:—While they were

playing with the ball, one of the children had, out of mischief, picked

it up and thrown it into the cannon, where it had stayed. They tried to

get it out by means of sticks, but could not reach it. Then Bert, always

plucky and enterprising to the verge of rashness, undertook to go after

the ball himself. The other boys at once joined forces to lift him up

and push him into the dark cavern, and then alarmed by his cries and

unavailing struggles to get out again, began to cry themselves, and thus

brought Mrs. Lloyd to the scene.

Mr. Lloyd was very much amused when he heard about Bert’s adventure.

“You’ve beaten Shakespeare, Bert,” said he, after a hearty laugh, as

Mrs. Lloyd graphically described the occurrence. “For Shakespeare says a

man does not seek the bubble reputation in the cannon’s mouth, until he

becomes a soldier, but you have found it, unless I am much mistaken,

before you have fairly begun being a schoolboy.”

Bert did not understand the reference to Shakespeare, but he did

understand that his father was not displeased with him, and that was a

much more important matter. The next Sunday afternoon, when they went

for their accustomed stroll in the fort, Bert showed his father the big

gun whose dark interior he had attempted to explore.

“Oh, but father, wasn’t I frightened when I got in there and couldn’t

get out again!” said he earnestly, clasping his father’s hand tightly,

as the horror of the situation came back to him.

“You were certainly in a tight place, little man,” answered Mr. Lloyd,

“and the next time your ball gets into one of the cannons you had better

ask one of the artillerymen to get it out for you. He will find it a

much easier job than getting you out.”

Bert loved the old fort and its cannons none the less because of his

adventure, and as he grew older he learned to drop down into it from the

garden fence, and climb back again, with the agility of a monkey. The

garden itself was not very extensive, but Bert took a great deal of

pleasure in it, too, for he was fond of flowers—what true boy, indeed,

is not? — and it contained a large number within its narrow limits,

there being no less than two score rose bushes of different varieties,

for instance. The roses were very plenteous and beautiful when in their

prime, but at opposite corners of the little garden stood two trees that

had far more interest for Bert than all the rose trees put together.

These were two apple trees, planted, no one knew just how or when, which

had been allowed to grow up at their own will, without pruning or

grafting, and, as a consequence, were never known to produce fruit that

was worth eating. Every spring they put forth a brave show of pink and

white blossoms, as though this year, at all events, they were going to

do themselves credit, and every autumn the result appeared in

half-a-dozen hard, small, sour, withered-up apples that hardly deserved

the name. And yet, although these trees showed no signs of repentance

and amendment, Bert, with the quenchless hopefulness of boyhood, never

quite despaired of their bringing forth an apple that he could eat

without having his mouth drawn up into one tight pucker. Autumn after

autumn he would watch the slowly developing fruit, trusting for the

best. It always abused his confidence, however, but it was a long time

before he finally gave it up in despair.

At one side of the garden stood a neat little barn that was also of

special interest to Bert, for, besides the stall for the cow, there was

another, still vacant, which Mr. Lloyd had promised should have a pony

for its tenant so soon as Bert was old enough to be trusted with such a

playmate.

Hardly a day passed that Bert did not go into the stable, and, standing

by the little stall, wonder to himself how it would look with a pretty

pony in it. Of course, he felt very impatient to have the pony, but Mr.

Lloyd had his own ideas upon that point, and was not to be moved from

them. He thought that when Bert was ten years old would be quite time

enough, and so there was nothing to do but to wait, which Bert did, with

as much fortitude as he could command.

Whatever might be the weather outside, it seemed always warm and sunny

indoors at Bert’s home. The Lloyds lived in an atmosphere of love, both

human and Divine. They loved one another dearly, but they loved God

still more, and lived close to Him. Religion was not so much expressed

as implied in their life. It was not in the least obtrusive, yet one

could never mistake their point of view. Next to its sincerity, the

strongest characteristic of their religion was its cheeriness. They saw

no reason why the children of the King should go mourning all their

days; on the contrary, was it not rather their duty, as well as their

privilege, to establish the joy of service?

Brought up amid such influences, Bert was, as a natural consequence,

entirely free from those strange misconceptions of the true character of

religion which keep so many of the young out of the kingdom. He saw

nothing gloomy or repellent in religion. That he should love and serve

God seemed as natural to him as that he should love and serve his

parents. Of their love and care he had a thousand tokens daily. Of the

Divine love and care he learned from them, and that they should believe

in it was all the reason he required for his doing the same. He asked no

further evidence.

There were, of course, times when the spirit of evil stirred within him,

and moved him to rebel against authority, and to wish, as he put it

himself one day when reminded of the text, “Thou God seest me,” that

“God would let him alone for a while, and not be always looking at him.”

But then he wasn’t an angel by any means, but simply a hearty, healthy,

happy boy, with a fair share of temper, and as much fondness for having

his own way as the average boy of his age.

His parents were very proud of him. They would have been queer parents

if they were not. Yet they were careful to disguise it from him as far

as possible. If there was one thing more than another that Mr. Lloyd

disliked in children, and, therefore, dreaded for his boy, it was that

forward, conscious air which comes of too much attention being paid them

in the presence of their elders. “Little folks should be seen and not

heard,” he would say kindly but firmly to Bert, when that young person

was disposed to unduly assert himself, and Bert rarely failed to take

the hint.

One trait of Bert’s nature which gave his father great gratification was

his fondness for reading. He never had to be taught to read. He learned,

himself. That is, he was so eager to learn that so soon as he had

mastered the alphabet, he was always taking his picture books to his

mother or sister, and getting them to spell the words for him. In this

way he got over all his difficulties with surprising rapidity, and at

five years of age could read quite easily. As he grew older, he showed

rather an odd taste in his choice of books. One volume that he read from

cover to cover before he was eight years old was Layard’s “Nineveh.”

Just why this portly sombre-hued volume, with its winged lion stamped in

gold upon its back, attracted him so strongly, it would not be easy to

say. The illustrations, of course, had something to do with it, and then

the fascination of digging down deep into the earth and bringing forth

all sorts of strange things no doubt influenced him.

Another book that held a wonderful charm for him was the Book of

Revelation. So carefully did he con this, which he thought the most

glorious of all writings, that at one time he could recite many chapters

of it word for word. Its marvellous imagery appealed to his imagination

if it did nothing more, and took such hold upon his mind that no part of

the Bible, not even the stories that shine like stars through the first

books of the Old Testament, was more interesting to him.

Not only was Bert’s imagination vivid, but his sympathies were also very

quick and easily aroused. It was scarcely safe to read to him a pathetic

tale, his tears were so certain to flow. The story of Gellert’s hound,

faithful unto death, well-nigh broke his heart, and that perfect pearl,

“Rab and His Friends,” bedewed his cheeks, although he read it again and

again until he knew it almost by heart.

No one ever laughed at his tenderness of heart. He was not taught that

it was unmanly for a boy to weep. It is an easy thing to chill and

harden an impressionable nature. It is not so easy to soften it again,

or to bring softness to one that is too hard for its own good.

With such a home, Bert Lloyd could hardly fail to be a happy boy, and no

one that knew him would ever have thought of him as being anything else.

He had his dull times, of course. What boy with all his faculties has

not? And he had his cranky spells, too. But neither the one nor the

other lasted very long, and the sunshine soon not only broke through the

clouds, but scattered them altogether. Happy are those natures not given

to brooding over real or fancied troubles. Gloom never mends matters: it

can only make them worse. |