|

SO keenly did Bert feel

his disgrace, that it was some time before he regained his wonted

spirits; and his continued depression gave his mother no little concern,

so that she took every way of showing to him that her confidence in him

was unimpaired, and that she asked no further proof of his penitence

than he had already given. But Bert’s sensitive nature had received a

shock from which it did not readily recover. From his earliest days he

had been peculiarly free from the desire to take what did not belong to

him; and as he grew older, this had developed into a positive aversion

to anything that savoured of stealing in the slightest degree. He never

could see any fun in “hooking” another boy’s lunch, as so many others

did, and nothing could induce him to join in one of the numerous

expeditions organised to raid sundry unguarded orchards in the outskirts

of the city.

His firmness upon this point led to a curious scene one afternoon.

School was just out, and a group of the boys, among whom were Bert, and,

of course, Frank Bowser, was discussing what they should do with

themselves, when Ned Ross proposed that they should go out to the

Hosterman orchard, and see if they could not get some apples. A chorus

of approval came from all but Bert, who immediately turned away and made

as though he would go home.

“Hallo! Bert,” cried Ned Ross, “aren’t you coming?”

“No,” replied Bert, very decidedly. “I’m not.” “Why not?” inquired Ned.

“What’s the matter?” “Those are not our apples, Ned, and we’ve got no

right to touch ’em,” answered Bert.

“Bosh and nonsense!” exclaimed Ned. “All the boys take them, and nobody

ever hinders them. Come along.”

“No,” said Bert, “I can’t.”

“Can’t? Why can’t you?” persisted Ned, who was rapidly losing his

temper.

Bert hesitated a moment, and the colour mounted high in his cheeks. Then

he spoke out his reason bravely:

“Because I’m a Christian, Ned; and it would not be right for me to do

it.”

“A Christian?” sneered Ned. “You’d be nearer the truth if you said a

coward.”

The words had hardly left his lips before Frank Bowser was standing

before him, shaking in his face a fist that was not to be regarded

lightly.

“Say that again,” cried Frank, wrathfully, “and I’ll knock you down!”

Ned looked at Frank’s face, and then at his fist. There was no mistaking

the purpose of either, and as Frank was fully his match, if not more, he

thought it prudent to say nothing more than: “Bah! Come on, fellows. We

can get along without him.”

The group moved off; but Bert was not the only one who stayed behind.

Frank stayed too; and so did Ernest Linton. And these three sought their

amusement in another direction.

That scene very vividly impressed Bert, and over and over again he

thought to himself: “What will the boys who heard me refuse to go to the

orchard, because I am a Christian, think of me when they hear that I

have been helping to spend stolen money?”

This was the thought that troubled him most, but it was not the only

one. He felt that he could not be at ease with his beloved Sunday-school

teacher again, until he had made a full confession to him. But, oh! this

did seem so hard to do! Several Sundays passed without his being able to

make up his mind to do it. At length he determined to put it off no

longer, and one Sunday afternoon, lingering behind after the school had

been dismissed, he poured the whole story into Mr. Silver’s sympathetic

ear.

Mr. Silver was evidently moved to the heart, as Bert, without sparing

himself, told of his disobedience, his concealment, and the consequences

that followed ; and he had many a wise and tender word for the boy,

whose confidence in him made him proud. From that day a peculiar

fondness existed between the two, and Mr. Silver was inspired to

increased fidelity and effort in his work because of the knowledge that

one at least of his boys looked upon him with such affection and

confidence.

Once that summer had fairly come to stay, the wharves of the city became

full of fascination for the boys, and every afternoon they trooped

thither to fish for perch and tommy cods; to board the vessels lying in

their berths, and out-do one another in feats of rigging climbing; to

play glorious games of “hide-and-seek,” and “I spy,” in the great

cavernous warehouses, and when tired to gather around some idle sailor,

and have him stir their imagination with marvellous stories of the sea.

For none had the wharves more attraction than for Bert and Frank, and

although Mrs. Lloyd would not allow the former to go down Water Street,

where he would be far from home, she did not object to his spending an

afternoon now and then on a wharf not far from their own house. So

thither the two friends repaired at every opportunity, and fine fun they

had, dropping their well-baited hooks into the clear green water, to

catch eager perch, or watching the hardworking sailors dragging huge

casks of molasses out of dark and grimy holds, and rolling them up the

wharf to be stored in the vast cool warehouses, or running risks of

being pickled themselves, as they followed the fish-curers in their work

of preparing the salt herring or mackerel for their journey to the hot

West Indies. There never was any lack of employment, for eyes, or hands,

or feet, on that busy wharf, and the boys felt very proud when they were

permitted to join the workers sometimes and do their little best, which

was all the more enjoyable because they could stop whenever they liked,

and hadn’t to work all day as the others did.

Nor were these the only attractions. The principal business done at this

wharf was with the West Indies, and no vessel thought of coming back

from that region of fruits without a goodly store of oranges, bananas,

and pine-apples, some of which, if the boys were not too troublesome,

and the captain had made a good voyage, were sure to find their way into

very appreciative mouths. Bert’s frank, bright manner, and plucky

spirit, made him a great favourite with the captains, and many a time

was he sent home with a big juicy pine, or an armful of great golden

oranges.

One day, when Bert and Frank went down to the wharf, they found a

strange-looking vessel made fast to the piles that filled them with

curiosity. She was a barquentine, and was sparred, and rigged, and

painted in a rather unusual way, the explanation of it all being that

she was a Spanish vessel, of an old-fashioned type. Quite in keeping

with the appearance of the vessel was the appearance of the crew. They

were nearly all Lascars, and with their tawny skins, flashing eyes, jet

black hair, and gold-ringed ears, seemed to fit very well the

description of the pirates, whose dreadful deeds, as graphically

described in sundry books, had given the boys many a delicious thrill of

horror. This resemblance caused them to look upon the foreigners with

some little fear at first, but their curiosity soon overcame all

considerations of prudence, and after hanging about for a while, they

bashfully accepted the invitation extended them by a swarthy sailor,

whose words were unintelligible, but whose meaning was unmistakable.

On board the Santa Maria—for that was the vessel’s name—they found much

to interest them, and the sailors treated them very kindly, in spite of

their piratical appearance. What delighted them most was a monkey that

belonged to the cook. He was one of the cutest, cleverest little

creatures that ever parodied humanity. His owner had taught him a good

many tricks, and he had taught himself even more; and both the boys felt

that in all their lives they had never seen so entertaining a pet. He

completely captivated them, and they would have given all they possessed

to make him their own. But the cook had no idea of parting with him,

even had it been in their power to buy him; so they had to content

themselves with going down to see him as often as they could.

Of course, they told their schoolmates about him, and of course the

schoolmates were set wild with curiosity to see this marvellous monkey,

and they flocked down to the Santa Maria in such numbers, and so often,

that at last the sailors got tired of them. A mob of schoolboys invading

the deck every afternoon, and paying uproarious homage to the cleverness

of a monkey, was more or less of a nuisance. Accordingly, by way of a

gentle hint, the rope ladder, by which easy access was had to the

vessel, was removed, and a single rope put in its place.

It happened that the first afternoon after this had been done, the crowd

of visitors was larger than ever; and when they arrived at the Santa

Maria's side, and found the ladder gone, they were, as may be easily

imagined, very much disgusted. A rope might be good enough for a sailor,

but the boys very much preferred a ladder, and they felt disposed to

resent the action of the sailors in thus cutting off their means of

ascent. The fact that it was high tide at the time, and the tall sides

of the ship towered above the wharf, constituted a further grievance in

the boys’ minds. They held an impromptu indignation meeting forthwith.

But, although they were unanimous in condemning the conduct of the

foreigners, who evidently did not know any better, they were still no

nearer the monkey.

“Why not try to shin up the rope?” asked Frank Bowser, after a while.

“All right, if you’ll give us a lead,” replied one of the others.

“Very well—here goes!” returned Frank. And without more ado he grasped

the rope, planted his feet firmly against the vessel’s side, and began

to ascend. It was evidently not the easiest thing in the world to do,

but his pluck, determination, and muscle conquered; and presently,

somewhat out of breath, he sat upon the bulwark, and, waving his cap to

the boys below, gasped out:

“Come along, boys! It’s as easy as winking.”

Not to be outdone, several others made the attempt and succeeded also.

Then came Bert’s turn. Although so many had got up all right, he somehow

felt a little nervous, and made one or two false starts, climbing up a

little way and then dropping back again. This caused those who were

waiting to become impatient, and while Bert was about making another

start, one of them who stood behind him gave him a sharp push, saying:

“Hurry up there, slow coach.”

As it happened, Bert was just at that moment changing his grip upon the

rope, and balancing himself upon the extreme edge of the stringer, which

formed the edge of the wharf. The ill-timed push caught him unawares. He

threw out his arms to steady himself, and the rope slipped altogether

from his grasp. The next instant, with a cry of fear that was taken up

by the boys standing helplessly about, he fell over into the dark,

swirling water, between the vessel’s side and the wharf.

Down, down, down he went, while the water roared in his ears with the

thunders of Niagara, and filled his mouth with its sickening brine, as

instinctively he opened it to cry for help. He could not swim a stroke,

but he had a good idea of what the motions were, and so now, in a

desperate effort to save his life, he struck out vigorously with his

hands. It must have helped him, too; for out of the darkness into which

he had been plunged at first, he emerged into a lighter place, where,

through the green water, he could see his hands looking very white, as

they moved before his face.

But this did not bring him to the surface; so he tried another plan.

Doubling his sturdy legs beneath him, he shot them out as he had seen

other boys do when “treading water.” A thrill of joy inspired him as the

effort succeeded, and, his head rising above the surface, he got one

good breath before sinking again. But the pitiless water engulfed him

once more, and, though he struggled hard, he seemed unable to keep

himself from sinking deeper still. Then the desire to struggle began to

leave him. Life seemed no longer a thing to be fiercely striven for. A

strange peace stole over his mind, and was followed by a still stranger

thing; for while he floated there, an unresisting prey to the deep, it

appeared as though all the events of his past life were crowding before

him like some wonderful panorama. From right to left they followed one

another in orderly procession, each as clear and distinct as a painted

picture, and he was watching them with absorbed, painless interest, when

something dark came across his vision; he felt himself grasped firmly

and drawn swiftly through the water, and the next thing he knew, he was

in the light and air again, and was being handed up to the top of the

wharf by men who passed him carefully from one to the other. In the very

nick of time rescue had come, and Bert was brought back to life.

Now, who was his rescuer, and what took place while Bert was struggling

for his life in the cold, dark water? The instant he disappeared the

boys shouted and shrieked in such a way as to bring the whole crew of

the Santa Maria to the bulwarks, over which they eagerly peered, not

understanding what was the matter. Frank, who was in a frenzy of anxiety

and alarm, tried hard to explain to them; but his efforts were

unavailing until the reappearance of Bert’s head made the matter plain

at once, and then he thought they would, of course, spring to the

rescue. But they did not. They looked at one another, and jabbered

something unintelligible, but not one of them moved, though Frank seized

the liveliest of them by the arm, and, pointing to the place where Bert

vanished, again indicated, by unmistakable gestures, what he wanted him

to do. The man simply shook his head and moved away. He either could not

swim, or did not think it worth while to risk his precious life in

trying to rescue one of the foreign urchins that had been bothering the

Santa Maria of late. Had Bert’s life depended upon these men, it might

have been given up at once.

But there was other help at hand. John Connors, the good-natured Irish

storekeeper, by whose sufferance the boys were permitted to make a

playground of the wharf, had heard their frantic cries, although he was

away up in one of the highest flats of the farthest store. Without

stopping to see what could be the matter, Connors leaped down the long

flights of stairs at a reckless rate, and ran toward the shrieking boys.

“Bert’s overboard—save him!” they cried, as he burst into their midst.

“Where?” he asked, breathlessly, while he flung off his boots.

“There—just there,” they replied, pointing to where Bert had last been

seen.

Balancing himself for an instant on the end of the stringer, Connors,

with the spring of a practised swimmer, dived into the depths and

disappeared; while the boys, in the silence of intense anxiety, crowded

as close as they dared to the edge of the wharf, and the Lascars looked

down from their bulwarks in stolid admiration. There were some moments

of harrowing uncertainty, and then a shout arose from the boys, which

even the swarthy sailors imitated, after a fashion ; for cleaving the

bubbled surface came the head of brave John Connors, and, close beside

it, the dripping curls of Bert Lloyd, the faces of both showing great

exhaustion.

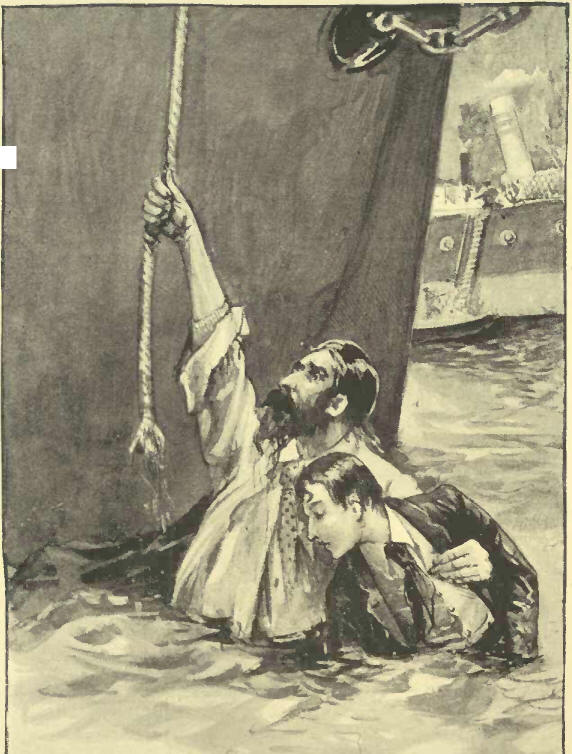

The sailors were all

alert now. Ropes were hastily flung over the side, and swarming down

these with the agility of monkeys, they took Bert out of his rescuer’s

hands and passed him up to the wharf; Connors followed unassisted, so

soon as he had recovered his breath.

Once upon the wharf, they were surrounded by a noisy group of boys,

overjoyed at their playmate’s happy escape from death, and overflowing

with admiration for his gallant rescuer. Bert very quickly came to

himself—for he had not indeed entirely lost consciousness—and then

Connors told him just how he had got hold of him :

“When I dived down first I couldn’t see anything of you at all, my boy,

and I went hunting about with my eyes wide open and looking for you. At

last, just as I was about giving you up, I saw something dark below me

that I thought might, perhaps, be yourself. So I just stuck out my foot,

and by the powers if it didn’t take you right under the chin. As quick

as a wink I drew you toward me, and once I had a good grip of you, I put

for the top as hard as I could go; and here we are now, safe and sound.

And, faith, I hope you won’t be trying it again in a hurry.”

Bert was very much in earnest when he assured him he would not, and

still more in earnest when he tried to express his gratitude. But

Connors would none of it.

“Not at all, not at all, my boy,” said he, with a laugh. “A fine young

chap like you is well worth saving any day, and it’s not in John Connors

to stand by and see you drown, even if those blackfaced furriners don’t

know any better.” |