|

FIVE years had passed

since Cuthbert Lloyd’s name was first inscribed in the big register on

Dr. Johnston’s desk, and he had been surely, steadily rising to the

proud position of being the first boy in the school, the “dux,” as the

doctor with his love for the classics preferred to call it.

And yet there were some branches of study that he still seemed unable to

get a good hold upon, or make satisfactory progress with. One of these

was algebra. For some reason or other, the hidden principles of this

puzzling science eluded his grasp, as though a and x had been eels of

phenomenal activity. He tried again and again to pierce the obscurity

that enshrouded them, but at best with imperfect success; and it was a

striking fact that he should, term after term, carry off the arithmetic

prize by splendid scores, and yet be ingloriously beaten at algebra.

Another subject that became a great bugbear to him was what was known as

composition. On Fridays the senior boys were required to bring an

original composition, covering at least two pages of letter paper, upon

any subject they saw fit. This requirement made that day “black Friday”

for Bert and many others besides. The writing of a letter or composition

is probably the hardest task that can be set before a schoolboy. It was

safe to say that in many cases a whipping would be gratefully preferred.

But for the disgrace of the thing, Bert would certainly rather at any

time have taken a mild whipping than sit down and write an essay.

At the first, taking pity upon his evident helplessness, Mr. Lloyd gave

him a good deal of assistance, or allowed Mary—the ever-willing and

ever-helpful Mary—to do so. But after a while he thought Bert should run

alone, and prohibited further aid. Thus thrown upon his own resources,

the poor fellow struggled hard, to very little purpose. Even when his

father gave him a lift to the extent of suggesting a good theme, he

found it almost impossible to write anything about it.

One Friday he went without having prepared a composition. He hoped that

Dr. Johnston would just keep him in after school for a while, or give

him an “imposition” of fifty lines of Virgil to copy as a penalty, and

that that would be an end of the matter. But, as it turned out, the

doctor thought otherwise. When Bert presented no composition he inquired

if he had any excuse, meaning a note from his father asking that he be

excused this time. Bert answered that he had not.

“Then,” said Dr. Johnston, sternly, “you must remain in after school

until your composition is written.”

Bert was a good deal troubled by this unexpected penalty, but there was

of course no appeal from the master’s decision. The school hours passed,

three o’clock came, and all the scholars save those who were kept in for

various shortcomings went joyfully off to their play, leaving the big,

bare, dreary room to the doctor and his prisoners. Then one by one, as

they met the conditions of their sentence, or made up their deficiencies

in work, they slipped quietly away, and ere the old yellow-faced clock

solemnly struck the hour of four, Bert was alone with the grim and

silent master.

He had not been idle during that hour. He had made more than one attempt

to prepare some sort of a composition, but both ideas and words utterly

failed him. He could not even think of a subject, much less cover two

pages of letter paper with comments upon it. By four o’clock despair had

settled down upon him, and he sat at his desk doing nothing, and waiting

he hardly knew for what.

Another hour passed, and still Bert had made no start, and still the

doctor sat at his desk absorbed in his book and apparently quite

oblivious of the boy before him. Six o’clock drew near, and with it the

early dusk of an autumn evening. Bert was growing faint with hunger,

and, oh! so weary of his confinement. Not until it was too dark to read

any longer did Dr. Johnston move; and then, without noticing Bert, he

went down the room, and disappeared through the door that led into his

own apartments:

“My gracious!” exclaimed Bert, in alarm. “Surely he is not going to

leave me here all alone in the dark. I’ll jump out of the window if he

does.”

But that was not the master’s idea, for shortly he returned with two

candles, placed one on either side of Bert’s desk, then went to his

desk, drew forth the long, black strap, whose cruel sting Bert had not

felt for years, and standing in front of the quaking boy, looking the

very type of unrelenting sternness, said:

“You shall not leave your seat until your composition is finished, and

if you have not made a beginning inside of five minutes you may expect

punishment.” So saying, he strode off into the darkness, and up and down

the long room, now filled with strange shadows, swishing the strap

against the desks as he passed to and fro. Bert’s feelings may be more

easily imagined than described. Hungry, weary, frightened, he grasped

his pen with trembling fingers, and bent over the paper.

For the first minute or two not a word was written. Then, as if struck

by some happy thought, he scribbled down a title quickly and paused. In

a moment more he wrote again, and soon one whole paragraph was done.

The five minutes having elapsed, the doctor emerged from the gloom and

came up to see what progress had been made. He looked over Bert’s

shoulder at the crooked lines that straggled over half the page, but he

could not have read more than the title, when the shadows of the great

empty room were startled by a peal of laughter that went echoing through

the darkness, and clapping the boy graciously upon his back, the master

said:

“That will do, Lloyd. The title is quite sufficient. You may go now;

”for he had a keen sense of humour and a thorough relish of a joke, and

the subject selected by Bert was peculiarly appropriate, being

“Necessity is the Mother of Invention.”

Mr. Lloyd was so delighted with Bert’s ingenuity that thenceforth he

gave him very effective assistance in the preparation of his weekly

essays, and they were no longer the bugbear that they had been.

It was not long after this that Bert had an experience with the law not

less memorable.

In an adjoining street, there lived a family by the name of Dodson, that

possessed a very large, old, and cross Newfoundland dog, which had, by

its frequent exhibitions of ill-temper, become quite a nuisance to the

neighbourhood. They had often been spoken to about their dog’s readiness

to snap at people, but had refused to chain him up, or send him away,

because they had a lively aversion to small boys, and old Lion was

certainly successful in causing them to give the Dodson premises a wide

berth.

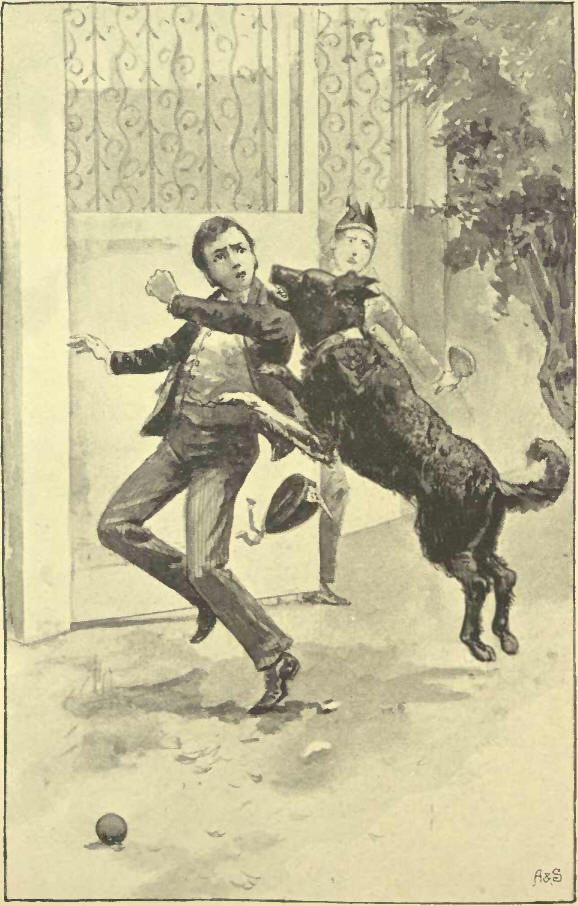

One afternoon Bert and Frank were going along the street playing catch

with a ball the former had just purchased, when, as they passed the

Dodson house, a wild throw from Frank sent the ball out of Bert’s reach,

and it rolled under the gate of the yard. Not thinking of the irascible

Lion in his haste to recover the ball, Bert opened the gate, and the

moment he did so, with a fierce growl the huge dog sprang at him and

fastened his teeth in his left cheek.

Bert shrieked with fright and pain, and in an instant Frank was beside

him, and had his strong hands tight round Lion’s throat. Immediately the

old dog let Bert go, and slunk off to his kennel, while Frank, seizing

his handkerchief, pressed it to the ugly wound in Bert’s cheek. Great

though the pain was, Bert quickly regained his self-possession, and

hastening home had his wounds covered with plaster. Fortunately, they

were not in any wise serious. They bled a good deal, and they promised

to spoil his beauty for a time at least, but, as there was no reason to

suppose that the dog was mad, that was the worst of them.

Mr. Lloyd was very much incensed when he saw Bert’s injuries, and heard

from him and Frank the particulars of the affair. He determined to make

one more appeal to the Dodsons to put the dog away, and if that were

unsuccessful, to call upon the authorities to compel them to do so.

“With a fierce growl the huge dog sprang

at him, and fastened his teeth in his left cheek.”

Another person who was

not less exercised about it was Michael, the man of all work. He was

very fond and proud of the young master, as he called Bert, and that a

dog should dare to put his teeth into him filled him with righteous

wrath. Furthermore, like many of his class, he firmly believed in the

superstition that unless the dog was killed at once, Bert would

certainly go mad. Mr. Lloyd laughed at him good-humouredly when he

earnestly advocated the summary execution of Lion, and refused to have

anything to do with it. But the faithful affectionate fellow was not to

be diverted from his purpose, and accordingly the next night after the

attack, he stealthily approached the Dodson yard from the rear, got

close to old Lion’s kennel, and then threw down before his very nose a

juicy bit of beefsteak, in which a strong dose of poison had been

cunningly concealed. The unsuspecting dog took the tempting bait, and

the next morning lay stiff and stark in death, before his kennel door.

When the Dodsons found their favourite dead, they were highly enraged;

and taking it for granted that either Mr. Lloyd or some one in his

interest or his employ was guilty of Lion’s untimely demise, Mr. Dodson,

without waiting to institute inquiries, rushed off to the City Police

Court, and lodged a complaint against the one who he conceived was the

guilty party.

Mr. Lloyd was not a little surprised when, later in the morning, a

blue-coated and silver-buttoned policeman presented himself at his

office, and, in the most respectful manner possible, served upon him a

summons to appear before the magistrate to answer to a complaint made by

one Thomas Dodson, who alleged that he “had with malice prepense and

aforethought killed or caused to be killed a certain Newfoundland dog,

the same being the property of the said Thomas Dodson, and thereby

caused damage to the complainant, to the amount of one hundred dollars.”

So soon as Mr. Lloyd read the summons, which was the first intimation he

had had of Lion’s taking off, he at once suspected who was the real

criminal. But of course he said nothing to the policeman beyond assuring

him that he would duly appear to answer to the summons.

That evening he sent for Michael, and without any words of explanation

placed the summons in his hand. The countenance of the honest fellow as

he slowly read it through and took in its import was an amusing study.

Bewilderment, surprise, indignation, and alarm were in turn expressed in

his frank face, and when he had finished he stood before Mr. Lloyd

speechless, but looking as though he wanted to say: “What will you be

after doing to me now, that I’ve got you into such a scrape?”

Assuming a seriousness he did not really feel, Mr. Lloyd looked hard at

Michael, as he asked:

“Do you know anything about this?”

Michael reddened, and dropped his eyes to the ground, but answered,

unhesitatingly:

“I do, sir. It was meself that gave the old brute the dose of medicine

that fixed him.”

“But, Michael,” said Mr. Lloyd, with difficulty restraining a smile, “it

was not right of you to take the law into your own hands in that way.

You knew well enough that I could not approve of it.”

“I did, indeed, sir,” answered Michael, “but,” lifting up his head as

his warm Irish heart stirred within him, “I couldn’t sleep at night for

thinking of what might happen to the young master if the dog weren’t

killed; and, so unbeknownst to anybody, I just slipped over the fence,

and dropped him a bit of steak that I knew he would take to kindly. I’m

very sorry, sir, if I’ve got you into any trouble, but sure can’t you

just tell them that it was Michael that did the mischief, and then they

won’t bother you at all.”

“No, no, Michael. I’m not going to do that. You meant for the best what

you did, and you did it for the sake of my boy, so I will assume the

responsibility; but I hope it will be a lesson to you not to take the

law into your own hands again. You see it is apt to have awkward

consequences.”

“That’s true, sir,” assented Michael, looking much relieved at this

conclusion. “I’ll promise to be careful next time, but—” pausing a

moment as he turned to leave the room—“it’s glad I am that that cross

old brute can’t have another chance at Master Bert, all the same.” And

having uttered this note of triumph, he made a low bow and disappeared.

Mr. Lloyd had a good laugh after the door closed upon him.

“He’s a faithful creature,” he said, kindly; “but I’m afraid his

fidelity is going to cost me something this time. However, I won’t make

him unhappy by letting him know that.”

The trial was fixed for the following Friday, and that day Bert was

excused from school in order to be present as a witness. His scars were

healing rapidly, but still presented an ugly enough appearance to make

it clear that worthy Michael’s indignation was not without cause.

Now, this was the first time that Bert had ever been inside a

court-room; and, although his father was a lawyer, the fact that he made

a rule never to carry his business home with him had caused Bert to grow

up in entire ignorance of the real nature of court proceedings. The only

trials that had ever interested him being those in which the life or

liberty of the person most deeply concerned was at stake, he had

naturally formed the idea that all trials were of this nature, and

consequently regarded with very lively sympathy the defendants of a

couple of cases that had the precedence of “Dodson v. Lloyd.”

Feeling quite sure that the unhappy individuals who were called upon to

defend themselves were in a very evil plight, he was surprised and

shocked at the callous levity of the lawyers, and even of the

magistrate, a small-sized man, to whom a full grey beard, a pair of

gold-bowed spectacles, and a deep voice imparted an air of dignity he

would not otherwise have possessed. That they should crack jokes with

each other over such serious matters was something he could not

understand, as with eyes and ears that missed nothing he observed all

that went on around him.

At length, after an hour or more of waiting, the case of “Dodson v.

Lloyd” was called, and Bert, now to his deep concern, beheld his father

in the same position as had been the persons whom he was just pitying;

for the magistrate, looking, as Bert thought, very stern, called upon

him to answer to the complaint of Thomas Dodson, who alleged, &c., &c.,

&c.

Mr. Lloyd pleaded his own cause, and it was not a very heavy

undertaking, for the simple reason that he made no defence beyond

stating that the dog had been poisoned by his servant without his

knowledge or approval, and asking that Bert’s injuries might be taken

into account in mitigation of damages. The magistrate accordingly asked

Bert to go into the witness-box, and the clerk administered the oath,

Bert kissing the greasy, old Bible that had in its time been touched by

many a perjured lip, with an unsophisticated fervour that brought out a

smile upon the countenances of the spectators.

He was then asked to give his version of the affair. Naturally enough,

he hesitated a little at first, but encouraged by his father’s smiles,

he soon got over his nervousness, and told a very plain, straightforward

story. Mr. Dodson’s lawyer, a short, thick man with a nose like a

paroquet’s, bushy, black whiskers, and a very obtrusive pair of

spectacles, then proceeded, in a rough, hard voice, to try his best to

draw Bert into admitting that he had been accustomed to tease the dog,

and to throw stones at him. But although he asked a number of questions

beginning with a “Now, sir, did you not?” or, “Now, sir, can you deny

that?” &c., uttered in very awe-inspiring tones, he did not succeed in

shaking Bert’s testimony in the slightest degree, or in entrapping him

into any disadvantageous admission.

At first Bert was somewhat disconcerted by the blustering, brow-beating

manner of the lawyer, but after a few questions his spirits rose to the

occasion, and he answered the questions in a prompt, frank, fearless

fashion, that more than once evoked a round of applause from the

lookers-on. He had nothing but the truth to tell and his cross-examiner

ere long came to the conclusion that it was futile endeavouring to get

him to tell anything else; and so, with rather bad grace, he gave it up,

and said he might go.

Before leaving the witness-box Bert removed the bandages from his cheek,

and exhibited the marks of the dog’s teeth to the magistrate, the sight

of which, together with the boy’s testimony, made such an impression

upon him that he gave as his decision that he would dismiss the case if

Mr. Lloyd would pay the costs, which the latter very readily agreed to

do; and so the matter ended—not quite to the satisfaction of Mr. Dodson,

but upon the whole in pretty close accordance with the strict principles

of right and justice.

Michael was very greatly relieved when he heard the result, for he had

been worrying a good deal over what he feared Mr. Lloyd might suffer in

consequence of his excess of zeal.

“So they got nothing for their old dog, after all,” he exclaimed, in

high glee. “Well, they got as much as he was worth at all events, and

”sinking his voice to a whisper—“ between you and me, Master Bert, if

another dog iver puts his teeth into you, I’ll be after givin’ him the

same medicine, so sure as my name’s Michael Flynn.” |