|

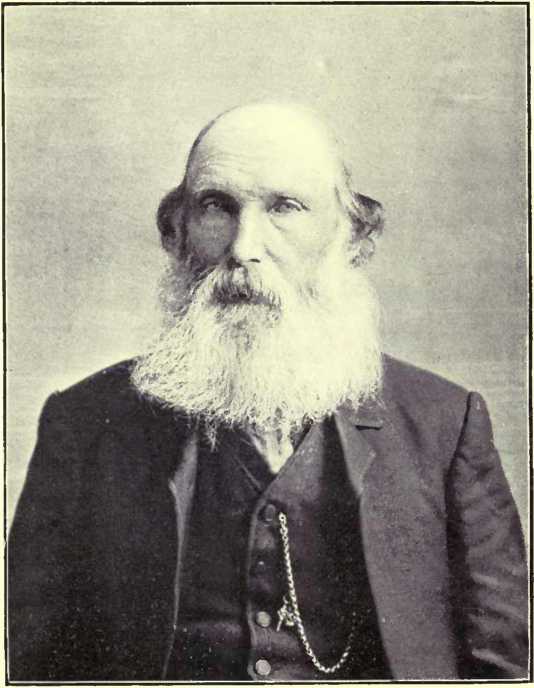

CAPTAIN JOHN CAMPBELL.

IN the group of

beautiful islands that lie west of the mainland of Argyle, and which

attract tourists from every corner- of the world, is the island of Jura.

Inconsiderable in itself, it seems to nestle in the bosom of its more

pretentious neighbor, the island of Islay. Away to the west rise lonely

and weirdlike Colonsay and Oronsay, on whose beetling cliffs dash the

wild waves of the Atlantic Ocean, that roll without interruption from

the icy hills of Greenland. On the mainland there looms up the scalp of

the lofty Ben Lomond, and farther north, above Loch Awe, rise the hills

round the dreary vale of Glencoe, where the perfidious Breadalbane

satisfied his unrelenting vengeance by the perpetration of the most vile

atrocity that ever disgraced any age or country. West of Glencoe are the

silent solitudes of Morven, and near which is Moidart, where Bonnie

Prince Charlie, of ill-starred fate, raised his standard in 1745, to

fight for the crown of Auld Scotland, the heritage of his fathers. Close

to the mainland here is the island of Iona, said to be the point at

which Christianity was first introduced into Scotland, and whose ruined

temples stand as silent memorials of the destroying hand of time, and

the evanescence of all earthly things. Such are the surroundings of the

little island of Jura, where the subject of this sketch was born on the

18th day of October, 1821. Mr. Campbell, or, as he is better known,

Capt. Campbell, was the son of a farmer who, in connection with the

operations on his farm, managed or acted as overseer on a larger holding

occupied by the Laird. In this capacity his transactions in buying and

selling of cattle and sheep were considerable, and led him in the course

of his business to the markets on the mainland, where the confidence

reposed in him by the Laird for his honesty and integrity allowed him

free scope in the disposal of the goods. In the ordinary course of

things, Mr. Campbell would likely have grown up and finally settled as a

shepherd or small farmer in his native Jura, but the death of his father

left him to some extent a free agent in choosing his own occupation in

life. Mr. Campbell being only ten years old at the time of the death of

his father, the widowed mother still kept the farm and managed to care

for and educate her son, who was her only child, till he attained the

age of seventeen. No son ever had a more kind and loving mother to watch

over him than Mr. Campbell.

After the death of her

husband her whole affections seemed to twine around him, and she was

untiring in ministering to his comfort and the happiness of his family.

And well did Mr. Campbell repay her for her kindness. No mother ever

received more affectionate care and treatment from a son than she did

from him. No matter whether he resided in a luxurious home in the city,

or dwelt in the log shanty, a cozy spot was reserved for her. His

conduct to her was most honorable to his head and creditable to his

heart. It is therefore not too much to say that he, or any other man

that shelters a mother in her widowhood, fulfils the highest attribute

of the divine teaching, and whatever his life may be as to faults and

failings, the world must be the better of his having lived.

At the age of seventeen

Mr. Campbell decided to try his fortune in Canada. Up to this period he

had been attending school and giving what assistance he could to his

mother on the farm. The island only contained two schools, so that he

had not much choice of teachers. But the parochial system introduced

into Scotland by John Knox, the great reformer, supplied to the youth of

that country a high standard of education. Mr. Campbell had availed

himself of this, so much so that when he came to Canada he at once

commenced teaching.

In the early summer of

1838 Mr. Campbell, accompanied by his mother, left his native land, she

never to see it again, and he not till nearly fifty years had passed

away. It was a brave undertaking to leave his friends and acquaintances

and cast his lot among strangers in a distant land. But hope is ever

high in the youthful breast. That buoyancy of heart which is peculiar to

the young leads them on to dare all circumstances and surmount

difficulties which, in after years, would appear to be insurmountable.

The voyage from Glasgow to Quebec lasted for ten weeks. In those days

the accommodation for the comfort and safety of the passengers was

deplorable. It is not to be wondered at if the sorrowing friends left

behind, as, with tears in their eyes, they sobbed a last farewell, would

rather have seen the departing ones going to their graves. But it is

said that fortune favors the brave. After the period of three months Mr.

Campbell had reached the end of his hopes and was settled in the

township of Darlington. He at once applied for and obtained a school,

but the teaching of a school in the backwoods of Canada did not accord

with his feelings. To a youth of his aspirations there was not much

prospect of advancement in a country school. Honorable as the occupation

undoubtedly is, it offered no prize for an ambitious youth. To be shut

up day after day, grinding through the routine of lessons with a few

small children in a little log school-house in the bush, did not

harmonize very well with the feelings of one who from his youth had

roamed among the hills and dales o,' he Western Highlands. There he was

free as the air of his native mountain; here his duty had to be done, so

long as he retained his position, in doing what he could for the little

ones committed to his care. His first year was his last one in the

profession) and he laid aside the taws, turning his back upon the

blackboard never again to return. He was now completing his nineteenth

year and naturally desired a wider sphere for his ambition. In his

island home he had been accustomed from his very infancy to look on the

sea. He was familiar with the ocean in all its various moods. He had

seen it raging like a lion and casting its white foam up to the very

door of the cottage where he dwelt, and he had seen it calm as a

sleeping child. For him a storm had no terrors, and a calm was simply

monotony. He determined therefore to go to sea, and from this time his

active life may be said to have begun.

At the age of nineteen

Mr. Campbell bade adieu to his friends and commenced his apprenticeship

as a sailor. It is said “there is no royal road to learning;” so there

was no royal road for him to a captaincy on the iuland seas of his

adopted country. He began his career at the bottom of the ladder, and

worked his way step by step to the top. As a deck hand he had to perform

the menial labor of a deck hand. He had no powerful interest at his back

to push him ahead. Whatever he accomplished in his new occupation he had

to do it himself. The position of a common sailor at that time did not

entitle him to much regard. His employers merely looked on him as

something that they could use for a consideration and at the end of the

season cast it off. There was only one way in which he could hope to

succeed (and this will apply to all young men starting life), and that

was by honestly discharging his duties and by taking such interest in

the business of his employers as to render himself necessary to the

successful carrying out of their speculations. This Mr. Campbell did

with a will and hearty endeavor that at once drew the attention of those

whose duty it was to watch over his conduct. At the end of his first

year before the mast his efforts in the interest of the owners merited

such appreciation that he was offered the command of a vessel for the

next season. This offer he declined. He did not consider that in the

short space of one year he had sufficiently mastered the details of his

business to assume the command of a vessel. He returned to Darlington to

his mother’s home for the winter. The next year he returned to his post

again before the mast, and served the season with great acceptance to

his employers, so much so that he was offered and accepted tlie position

of mate. During the few years he had been on deck, with the

characteristic frugality of his nation, he had saved his earnings. When

at the age of twenty-five years he received the appointment on the ship

Minerva, he bought an interest in this vessel, on which he held the

command for three years.

The Province of Ontario

was being settled rapidly at this time, both in the centre and in the

west, which greatly increased the trade from the various ports on Lake

Ontario. To accommodate this increased traffic the Canadian Government

decided to make certain improvements in the harbors between Toronto and

Kingston. The conduct of Mr. Campbell had attracted the attention of the

authorities, and he was offered and accepted the position of

superintendent of the survey and deepening the harbor at Cobourg. He at

once gave up the captaincy on the Minerva and entered on his duties as

manager of the Cobourg harbor improvements. He continued in this service

until the work was completed and a channel dredged to deep water with

such skill and care that it has required but little attention ever

since.

At the completion of

this work he removed to Col-borne, on Lake Ontario. Here he

superintended the building of the ship Trade Wind, in which craft he

also had an interest. This vessel is still afloat. He was appointed

captain and sailed her for one year. It is important to note here that

no Canadian ship had ever sailed to Chicago, which was then being spoken

of as a point of some importance on Lake Michigan. Nearly all the

trading with the few ships owned in Ontario at that time was done

between Buffalo, Oswego, Kingston, and intermediate ports on Lake

Ontario. The vast country away to the north and west was still a

wilderness. Except a few brave adventurers, no white man had penetrated

very far into the prairie solitudes, which are to-day the garden of

America. During the few years that Mr. Campbell sailed before the mast

he made several trips to Chicago and Milwaukee on American vessels, but

never on a Canadian. The honor of first sailing into Chicago under the

British flag was to be his own, as will be noticed later on. After

leaving this vessel the Captain’s next appointment was to the command of

the Water Witch, which at that time was owned in Buffalo, by an American

gentleman of somewhat eccentric character. This appointment he looks

upon as one of the strange events in his life. He is somewhat of a

fatalist in his opinions. He thinks with Hamlet “That there are more

things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamed of in thy

philosophy.” On a wild and stormy season, about the middle of November,

Mr. Campbell was in the city of Buffalo. It was near the close of

navigation on the lakes, and ships were fast making for their winter

quarters. He was sick and confined to his bed in a hotel frequented by

the sailors and captains navigating the lakes. One evening a gentleman

called and asked the proprietor if among the seamen at his house he

could get one to go with him to Chicago. Several men presented

themselves, but were not suitable. On further questioning, the

proprietor of the hotel informed him that there was only one hand he had

not seen, and he was sick in his room. The gentleman went to the room

where Mr. Campbell lay, and at once pronounced him to be the very man he

was looking for. Although never having seen each other before, it was

arranged that the ship should not sail for a couple of days till he

would be well enough to go aboard. In a day or two they sailed, the

owner of the ship in command. The weather was rough and the lake seemed

to be swept to its very depths by a terrific storm. As evening came on

the wind grew more wild and increased in fury. A long, dark night was

fast settling down on the troubled waters. Great seas swept over the

deck and threatened every moment to suck her down to destruction with

all on board. The Captain was incapable, and appeared helpless when the

fate of all on board depended to a considerable extent on his judgment.

The gale was still increasing. The rolling of the ship and the water

rushing over her decks made it dangerous for the men to attend to any

duty. The Captain at last asked if any one on board could take the

vessel through the channel to which they were fast approaching. All

declined, when Mr. Campbell informed him that he had passed through the

channel several times when a deck hand, but never as commander. Mr.

Campbell was at once put in command of the ship. The steersman was

ordered to steer according as he directed. At this part of the lake

there are two channels, one on the American and the other on the

Canadian side. The Canadian one, though narrower, he considered safer.

He gave directions to steer for the Canadian side. It was now dark, and

the gale was apparently increasing. The sound of the rushing waters as

they dashed on the ship, and the wind whistling in the cordage of the

masts, made it almost impossible for orders to be heard. On this

occasion Mr. Campbell says he trembled as he stood at his post.

It was the only time in

his life as a sailor that he ever knew fear. But he had to do his duty,

and his duty he did like a man. The safety of the ship and all the lives

on board were commited to his charge. As he stood at the watch his

garments were soaked with water and the night was cold. But on they

plunged through the darkness and the tumultuous waters. At length the

grey dawn began to brighten in the east, and he found that the danger

was past as they slowly entered the Detroit River. ‘When they arrived at

Chicago the owner of the ship gave instructions to him to fit her up to

suit himself and sail her where he pleased. Thus he became Captain of

the Water Witch, whose deck was his home till he left the lakes for a

farm in Blanshard. He accordingly returned to Canada, refitted the ship,

hoisted the British flag, sailed from Kingston to Chicago with a cargo

of Liverpool salt for Mr. Armour, the great speculator of the west. This

then is the first occasion on which the British flag was ever seen in

the Chicago river, flying from the masts of a Canadian ship. While he

was in port Mr. Armour drove him out to his pork-packing establishment,

which was then considerable and formed the neucleus of the vast business

of the present. In the course of his little trip Mr. Campbell noticed a

number of excrescences on Mr. Armour’s hands, which the vulgar people

call warts. The Captain, no doubt, in his younger days had heard and

read of Esculapius, but whether he knew anything of the compounds of

lard and smut prepared by that ancient practitioner for the cure of

these things, history sayeth not. This, however, history doth say, that

he applied a charm known only to himself, (it was in Gaelic), and on his

next visit to Chicago Mr. Armour presented himself on the ship with

hands as smooth and white as a rector’s. The cure was complete. But

there being no cordwood in that Prairie City to reward the new disciple

of Galen, Mr. Armour’s gratitude for such happy results took the shape

of a barrel of pork.

There is yet another

incident we must relate in connection with this voyage. Being in port at

Kingston, Mr. Campbell was introduced to a gentleman from England, Mi'.

J. Edward Wilkins. This gentleman was of good family, but reduced in

circumstances. He afterwards made several trips on Mr. Campbell’s ship

to ports on the lower Lakes. On this occasion he came with him as far as

Chicago. At that time there was no British Consul in the city, and he

experienced much difficulty, as the master of a foreign vessel, in

getting his papers to trade in a foreign port. Mr. Wilkins became aware

of this fact and informed him that if he would state all the

difficulties in connection therewith, he would memorialize the British

Government to appoint a consul at this point. Mr. Campbell accordingly

drew up a paper setting forth the whole case, which Mr. Wilkins put in

proper form and sent to the Old Country. Mr. Wilkins seems to have had

influence enough with some of the members of the government in London to

insure prompt attention to the memorial-A few months later an answer

came to Mr. Wilkins acknowledging the receipt of the papers and also

another document appointing him as the first British Consul in the city.

Thus Mr. Campbell has not only the honor of sailing the first ship

carrying British colors into Chicago, but also the honor of being

instrumental in the appointment of the first British Consul. We have

thus followed him from the period of his teaching in the little log

school in the backwoods up to the distinguished place he then held as

one of the most competent and painstaking masters sailing on the Great

Lakes.

HIS MARRIAGE

We must now return in

our narrative to a period some years prior to those occurrences which we

have related. There are events transpiring in the life of every man the

effects of which sometimes change the whole course of events, and give a

different coloring to his future conduct. Almost every man who has

reached the three score, in looking back over his career will be able to

point to such, that stand like milestones on his track, and by which he

sums up his existence, rather than by those mechanical methods

introduced by civilized nations for the computation of time. From one of

these points we will again proceed with this sketch. On the 22nd of

December, 1848, Mr. Campbell was united in marriage to Margaret

McDougall, the daughter of a farmer in Darlington. It is presumable that

this lady was one of his former pupils, when he taught the school in the

woods. She was several years his junior, being 18 years old, Mr.

Campbell being 26. After his marriage he removed to Kingston, where he

resided for some years. Mrs. Campbell, although having lived all her

life on a farm, was a good sailor and made a number of trips with her

husband, going as far west as Chicago. But city life had no charms for

her. She still was anxious to return to the farm. Mr. Campbell, though

still young, was threatened with failing health. The exposure arising

from the nature of his calling began to tell on him. He felt that to

stay on the deck much longer was to incur a serious risk. A young family

was growing up around him, and the solicitations of his wife, added to

those of his mother, finally influenced him to leave his chosen

occupation and go to a farm. To decide with him was to act. He sold off

his household goods, and early in the fifties came into the Township of

Blanshard. He had paid a visit to the township in 1843, when it was a

wilderness, and located what was afterwards the Dawson farm, but failed

to complete the arrangements and thereby lost the property. During his

visit in 1843 he was so much impressed with the country that as soon as

he determined to live on the farm, he at once came to Blanshard.

COMING TO BLANSHARD

Near the top of the

hill that rises from the banks of Fish Creek there stood in the early

fifties a shanty in the centre of a small clearing. This was on lot 6,

in the 9th concession. Into this humble dwelling he removed his

household goods. The change must have been very great indeed to one who

had followed his mode of life. This man who had been the first to carry

the flag of his country into the new centre of the west, and who was

instrumental in having a consul appointed to facilitate the transaction

of business between the two countries, must have had more than an

ordinary share of philosophy to submit to such a change. But he had seen

what had been accomplished in the older settlements. He had seen the

shanty give place to a home, if not of luxury, at least of comfort. He

had seen men on the farm, after the great fight with nature was over,

spend their remaining years on the fertile acres they had hewed from the

forest, in ease and contentment. What had been done by one in this

manner another might accomplish. He determined to try. It will be easily

understood that Mr. Campbell would be greatly handicapped in his efforts

at clearing a farm or carrying out the details of farm management. But

he was nobly supported by his wife. There was no detail of the farm with

which she was not conversant. Margaret, as he called her, was always

consulted, and it was well for him that he usually acted as she advised.

She was master of every piece of farm work, either indoors or out of

doors. She was a great worker in the field, in the dairy, and in the

stable. Slightly built and wiry looking, she appeared never to be

fatigued. It is not too much to say that the proprietor of “Stewart

Castle” owes much of the comfort and luxurious belongings of his present

condition to the untiring energy and industry of his wife. His new farm

had to be cleared, however, and he started with a will. He had the honor

of raising the first frame bam in that part of the township. Every

winter a fallow was chopped down; then logged and fenced the next

summer. He was a prosperous man. He had cattle in the yard, hogs in the

pen, and, what was then a rare thing in that part of the township,

horses in the stable. These horses were for several years the plague of

his life. He fed them well, and being of nervous temperament, they were

difficult to manage. It was one of the sights of a lifetime to see him

after Dan and Jim, as he called them, plowing a new, stumpy field with a

shovel plow. They went like deer over knolls, through hollows, round big

stumps, Mr. Campbell holding on to the handles like grim death. Here and

there he would catch on a big root, which would fly back and strike him

on the shin with terrible force. This would provoke an outpouring of the

spirit in words which separately and by themselves were not

unscriptural, but he had the faculty of placing them in such

combinations as are not taught in Sunday-schools.

FIRST LOG RAISING

It is now nearly forty

years since we met at Mr. Campbell’s place to raise his first log

building. This building still stands, a monument to the skill and

handiwork of the old pioneers. It was a delightful morning, about the

beginning of April. The frost of the previous night was fast giving way

before a hot sun that shone from a cloudless sky. Here and there in the

still woods one could see the curling smoke rise from the various sugar

camps where the supply of sweets was being made for the summer. Along

the concessions and side-roads and emerging from the woods, men could be

seen coming to assist in the raising. On our arrival our attention was

first attracted by the kindly salutation of the grog boss, who was

already on the ground with a teacup and an immense jug of what was

recommended as the pure stuff. All the hands took what was called a

“corker,” to relieve the fatigue of the walking. A “corker” was never

taken except in the morning. The potations indulged in during the day

were called “a wee tint,” which being interpreted meant “a half cupful.”

The corner men were now in their places and sharpening their axes ready

to lay down the logs as they came up. The “togglers” were preparing the

toggling-timber for the doors. The oxen were hauling the “skids” and the

“mulley’s.” Handspikes were being got ready, the short skids peeled and

mulleys pinned and tied at the forked end. At last a great log was

hauled by the oxen in front of the foundation and across the bottom of

the skids. Then the noise began. The shouting, the yelling, and

hurrahing could be heard far away in the woods. Every man lifted all he

could and shouted all he could. Babel was but a trifle to the noise and

confusion at the raising of a log building. Here you could hear the

voice of an Irishman shouting “tear-anages! send her up or smash her!”

Again you would hear the snort of a Yorkshireman counselling milder

measures than “smashing her.” There could be heard a volley of Gaelic

from a champion from the braes of Strathpieffer, while away above the

din, in a shrill treble voice, an old son of the heather yelled,

“chairge her! hoo the diel dinna yae chairge her % ” At last the log

reached the “corner men,” who placed it in position with a dexterity

truly marvellous. So we followed round the building till the first round

was in place. The sun had now taken effect on the frozen ground, and the

mud was almost without bottom. At length the noon hour arrived, when

helter-skelter all hands started for the shanty. At that time the hog

supplied the only animal food that was used among the old settlers. A

glance at the walls of Mr. Campbell’s dwelling showed that he had made

ample provision for the family. Great hams and sides of pork hung

everywhere. On the tables for the men was pork fried, pork roasted, and

pork boiled. There was pork in slices, pork in whangs, and pork in

chunks ; mashed potatoes by the peck, and great pyramids of sliced bread

were piled here on the board and flanked by several bottles of the “pure

stuff.” All this was the sort of food for men who, every day of their

lives, had to undergo the severest physical toil. As the supplies on the

board disappeared fresh augmentations were brought from side tables and

placed in position, which in turn were demolished with promptness and

despatch, affording the strongest proof of the palatability of the

viands, and the unappeasable appetite of the guests. But it is possible

to satisfy even a hungry pioneer, and the men returned to complete the

work of finishing the building, all happy and pleased with themselves.

PERSONAL TRAITS

Mr. Campbell, during

his long period of nearly fifty years’ residence in Blanshard, has never

taken a very active part in the public affairs of the municipality. Had

he been so disposed he might have filled the highest offices in the gift

of the people. But he was rather of a retiring disposition and never

courted popularity. In all the questions that have come before the

people of the township he always took part in the discussion in

connection with them, but left their final settlement to other men. He

was township assessor for one year, and on presentation of his roll

received a vote of thanks from the Council for the best roll that up to

that time had ever been given to the Board. He also filled the office of

auditor for over twenty years, which was always conferred on him without

being asked. He is a most hospitable man, and “Stewart Castle” is widely

known for its generous and kind treatment of his many friends or of the

stranger that may come within its gates. He is a most intense Jacobite

and reveres the memories of the ill-fated Stuart. He glories in the fact

that after the annihilation of their hopes on the field of Culloden, no

one among his famishing and persecuted countrymen could be found to sell

the blood of poor unfortunate Prince Charles. The pitiable story of Mary

Stuart, her splendor and her misfortunes, always excites his deepest

feelings. The thought of the cruelties and indignities to which she was

subjected by her persecutors rouse his strongest execrations. He seems

to lose faith in the divine plan for building up the brotherhood of man,

when it has to be cemented by the blood of the noble and the brave, and

the tears of the helpless and broken hearted. He is passionately fond of

music, and particularly the songs of his native country. As a performer,

our regard for truth forbids us giving him a high place. His masterpiece

is “ Burns and his Highland Mary,” and his rendering of that melody is

such that we could not recommend any person to go far to hear it. In the

musical line this was always his highest and last flight, and I believe

his audiences were always glad of it. As a dancer, even at the age of

nearly fourscore years, he is perfect, and his performances are such as

to excite the most fervent admiration of the devotees of the

terpsichorean art. In politics he has been a life-long Reformer, but is

not obtrusive with his opinions, rarely speaking about political

matters. He is an adherent of the Presbyterian Church, but takes no

active part in the affairs of religion.

In personal appearance,

thirty-five years ago, when he was at his best, he was strong and robust

looking, about average height, deep chested, straight, and well

proportioned. He is kindly in his family, although not at all

demonstrative in his affections. He is most honorable in all his

relations with his fellowmen. He is a true Scotchman, and glories in the

success of auld Scotia's sons. But we must now close this imperfect

sketch of the life of Captain John Campbell. In doing so we can heartily

endorse the kindly feelings expressed by his numerous friends at his

golden wedding, on the 22nd of December last. We therefore, in common

with all his well-wishers, trust that he may be long spared to toddle

around “Stewart Castle,” and that the evening of his life may calmly

glide away into the sunset, when the grim reaper comes forth to gather

in the sheaves. |