|

THERE are perhaps few

of Blanshard’s old settlers who at the outset of their career had a more

chequered life than Mr. James Dinsmore, the subject of the following

sketch. He was of sanguine temperament, restless and energetic in his

disposition. He had great independence of character, and considered

himself equal to any man, no matter what his social position may have

been. He was untiring in industry, and zealous in the prosecution of any

scheme, either for his own or the public good. He was a confiding and

open-hearted friend, but persevering and implacable in the denunciation

of his opponents. He was somewhat deficient in tact, and his political

efforts were carried to success, not by an adroit exercise of those

qualities that raise politicians to power, but by the strength of his

representations and an honest, manly advocacy of those principles which

he conceived to be just and right. Such are a few of the most prominent

points in the character of this man who for many years wielded great

influence in Blanshard, and to some extent divided the representative

honors with Mr. Cathcart, his great opponent.

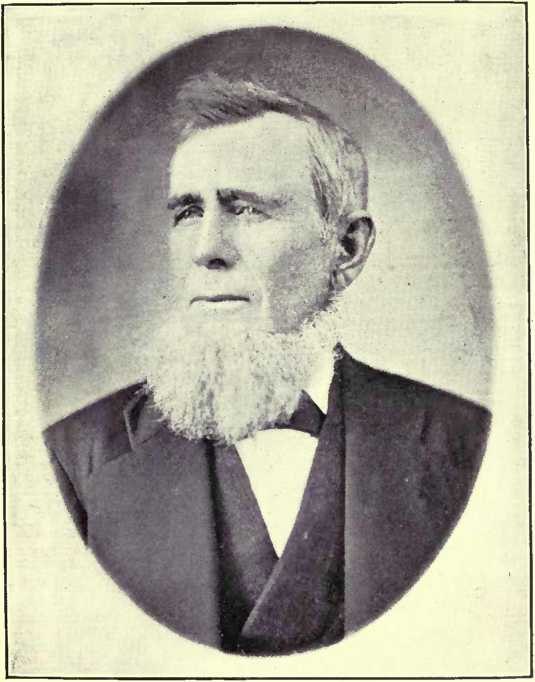

JAMES DINSMORE.

James Dinsmore was born

in the parish of Drumholm, County of Donegal, Ireland, on the 21st day

of March, 1821—over 78 years ago. Like almost all the old settlers of

Blanshard, he was the son of a farmer, and on the farm he spent his

boyhood, attending school in the town of Donegal until he was able by

his labor to contribute to his own support. His father had been actively

engaged during the troubles in Ireland at the latter part of the

eighteenth century on the side of the Government. The tales of that

momentous period in the history of his native country, and of the

terrible trials and dangers to those who espoused the cause of the

ruling power, had often been told by his parents as they sat around the

turf fire in the long winter nights. These old stories made a great

impression on his young mind, so much so that they to some extent

influenced his manner of thought during his life. Although his politics

were practically democratic, he was most loyal to the flag of old

Britain. He felt a pride in the fact that he was born a subject of a

great and most glorious throne that is yet destined to sway the

destinies of the world.

His father’s

circumstances were not such as would enable him to give his sons much

assistance at their outset in life. Five young, energetic lads were

growing up around him, and he saw that a change in his condition would

have to be made soon. The agents of the Canada Company had at this

period permeated the northern part of the Emerald Isle, inducing the

struggling population of that over-populated country to leave old

Ireland and go to the new fertile land of the West. Whatever may be said

regarding the methods of the Company in the sale and manipulation of

their great estate, there can be but one opinion as to the class of

settlers that took up their lands. A more hardy, energetic, honest,

persevering body of men never made homes for themselves anywhere on the

American continent. Of this contingent Blanshard fortunately got her

full share. The Dinsmores of the tenth concession, the Cathcarts and

Creightons on the Base Line, the Switzers on the north side of the

township, the Armstrongs and McCulloughs on the Mitchell Road, have made

a record most honorable for themselves and which should have a marked

influence on the rising generation. These, with many other good and

noble men that have long since passed away, laid deep the foundations of

the prosperity of what is considered one of the most progressive

townships in the west.

It was therefore

decided that the little holding in Donegal should be disposed of, and

new homes sought in the great country on the other side of the Atlantic

Ocean. Accordingly, in the spring of 1835, the family bade adieu to old

Ireland and all her associations, and which no one of them ever saw

more. To the younger members of a household it is always an easy matter

to remove and change their locality ; in fact the very essence of young

life consists in change and variety. But with the old or middle aged it

is very different. Ties spring up around them as years pass by, light as

air seemingly in themselves, yet stronger than bands of steel.

“The dear affections of

the heart

Outlive the forms that give them birth.”

After ten weeks of a

dreary, stormy voyage they arrived at Quebec, and coming on west reached

the city of Kingston, where they remained one year. The family then left

Kingston and came to Toronto. After staying in Toronto for about a year,

Mr. Dinsmore, the elder, removed to a farm in Toronto Township. During

all these years the family had all remained together; but the time had

now come when some of the young men should branch out for themselves.

The subject of our sketch therefore determined, young as he was, to face

the stern realities of life. He was then sixteen years of age, at which

period not many young men think of putting on the harness for

themselves. But he was not afraid that any circumstance or condition of

things would arise with which he would not be able to cope successfully.

His independence of thought and feeling, coupled with his natural

impetuosity of character, urged him on into the stream, sink or swim. He

made up his mind to embrace the first opportunity whereby he could make

an honest living. His initiatory step, as one of the toilers of the

great world, was in the capacity of bartender in a hotel. The hostlery

known as the Edinburgh Castle, in Toronto, was kept by an old Scotchman

who had fought through the Peninsular War with Wellington, and was on

the celebrated field of Waterloo, where he contributed by his valor to

the defeat of that great scourge of the world, Napoleon Bonaparte. He

did not remain long behind the bar, although he had given satisfaction

to his employer.

Events were then

transpiring in Upper Canada (as it was then called) which shook society

to its very centre and threatened for a time to overturn the Government.

A little clique of politicians, known as the Family Compact, had grasped

the whole power and patronage of this province in their own hands. Some

of these were most unprincipled men, and had established an oligarchy

that would undoubtedly have destroyed the liberties of the people and

sapped the prosperity of the young and growing province. But happily for

the people of this country, a young and irrepressible Scotchman had

espoused the cause of the settlers. For years he fought out his

self-imposed task and stood as the first champion for free

representation and responsible Government. Though we deplore the

terrible extreme to which he ultimately led a large section of the

Canadians, few men will deny that the political results since the

struggle of 1837 are, to a large extent, owing to his fearless conduct

in defending the rights of the poor settlers who were seeking a home in

this country. Time is dealing kindly with the memory of this great man,

and the day will come when he will be looked on as one of those

unselfish spirits who lay upon the altar of their country all they have

in the world, as an offering for the liberties of their fellowmen. From

the early training Mr. Dinsmore had received, and from his intense

loyalty to the old land, we can experience no difficulty in finding what

his sentiments were on this occasion. Young as he was, he at once

enlisted under Captain Price, and shouldering his gun, joined the ranks

as a volunteer in Captain Price’s corps. He served for about six months,

when, considering his youth and a not very robust constitution, he was

amongst the first to be discharged when the rising had collapsed. The

next time we hear of Mr. Dinsmore is in the capacity of a deck-hand on

board the steamer William IV. The life of a sailor apparently was not to

his taste, as he only stayed at this business for one season. After

associating for some time with a gang of framers, he entered into the

employ of a bankrupt stock dealer, in Brampton. Here he first essayed

the business of auctioneer at the age of twenty years, and continued to

swing the hammer almost continuously till he had reached the age of

sixty-nine. The business of an auctioneer was exactly suited to his

nature, and, as might be expected, he excelled in it. His services were

in request all over a large section of the country. He knew men well,

and being naturally full of Irish wit, had the happy faculty of keeping

the bidders in the best of humor.

Thus far he had led a

rather roving and unsettled life. We next find him in the lumber woods

on the Grand River, at which occupation he remained for three or four

years. The time had now arrived when it was necessary to adopt some plan

for his future career. The new township of Blanshard had been thrown

open for settlement in 1840. His father, with his other brothers, had

still remained on the rented farm in Toronto township. But the life of a

tenant on a rented farm did not offer much inducement for a man with a

growing family around him. By going into a new country they might have

to undergo hardship and inconvenience for a few years. With industry and

economy all this would undoubtedly be overcome. The labor they had to

spend in the rented place to pay the rent might be better expended in

making a farm for themselves. Ho it was decided to try their fortune in

the new' township. In the fall of 1842 the elder Mr. Dinsmore came west,

and located a place for himself and one for each of his sons, and formed

what is known as the Dinsmore settlement.

John, the eldest, took

lot 14, James lot 16, Thomas lot 20, in the tenth concession, Samuel and

David lots 16, 17, and 18, in the eleventh concession. This part of the

township at that time was a complete wilderness. Only one or two

settlers had preceded them. There were no roads, no marks to show

anywhere that the foot of the white man ever trod those wilds, except

the survey post, and an occasional blaze on the trees. But they had

confidence in themselves and in the future of the country. The Dinsmore

settlement was soon known as one of the most progressive sections in

Blanshard. The whole of the brothers were much alike in their nature,

steady and industrious, and of unimpeachable integrity. It is pleasing

to note that this family were, in the course of time, amply rewarded for

their perseverance by attaining comfort and a competence for old age.

The greatest difficulty that most of the old settlers had to encounter

in their new homes was the want of money to obtain the commonest

necessaries of life. To overcome this circumstance James Dinsmore, with

his father and brothers, had for two or three seasons to go back to

Toronto township in the summer for the purpose of earning a few dollars

to enable them to purchase food for the winter. Returning to the woods

in the fall of the year, they chopped down the forest till spring, and

thus, although very slow progress was made, something was being done.

They built shanties and cleared small patches for potatoes and wheat,

and so came on by degrees, still hoping and still doing. The journey

back and forth between Blanshard and Toronto was made on foot. It was a

great undertaking to trudge away for one hundred miles, much of it over

bad roads and through a wild country, but it is said “the back s aye

made for the burden;” and these old pioneers surely “run the race set

before them” nobly and well.

He had now reached the

period when most men experience a desire to become settled in life. It

was therefore necessary that he should take to himself a partner to

share his joys and his sorrows, for joy and sorrow seem to be the lot of

all. He had been fairly prosperous in his farming operations. He could

boast of a good farm, a shanty, a pig in the pen, cows in the yard, and

a yoke of oxen. All this now-a-days would not be considered a great

fortune to offer to a young lady in return for her affections ; but it

was all he had to offer. No doubt in thinking the matter over in his

mind, he could not very well understand how with all these, his whole

worldly goods, placed in the balance on one side, and himself thrown in,

the scale on the other side, with the affections of a sensible young

lady, would not touch the beam. Young marriageable women in the township

of Blanshard at that time were rather a scarce article. Like most young

men, while he had been preparing the cage he had been watching for some

fair one to place in it. Summoning up his whole store of fortitude, he

went to the township of London, and on the 4th of February, 1847, was

able to call Miss Rebecca Freeborne his wife. This was the greatest

piece of good fortune of his life. For over fifty years they have lived

along together, Mrs. Dinsmore being in every way a most estimable

person, a dutiful and affectionate wife. She was always light-hearted

and gay, until the hand of affliction, a few years ago, fell heavily

upon her in the loss of her daughter. Still even now, at her advanced

age, her eyes, which were black and piercing, sparkle with jollity and

good nature. She was always ready to second his efforts in everything

that tended to his good or that of his family; and like many men in the

world, he owes much of his success to the good counsel of his wife. His

family consisted of nine children, two of whom are dead, John and

Margaret. Those living are, Andrew, in Imlay City, Mich.; Mrs. T.

Robinson (Jane), London township; Mrs. Robinson, (Mary Ann), also of

London township ; Samuel, at home ; Nelson, in Manitoba; Wellington, on

the old homestead ; and Newman, in California. But time and tide wait

for no man ; and as years passed away he was, at the end of the fifties,

one of the wealthiest farmers in the township. He had, shortly after

coming to Blanshard, taken up the business of auctioneering, a manner of

life, as we have said elsewhere, entirely in accordance with his taste.

In this business his reputation extended over a wide circle. The

townships of London, Biddulph, Blanshard, Us-borne, Downie, Fullarton,

and the Nissouris, all required his services. There is scarcely a road

in any of these municipalities that he has not traversed at all hours of

the night. No matter how far away he had been, he never, without a

single exception, failed to get to his own home. Although not robust

looking, he had a constitution of iron; otherwise he must long ere now

have succumbed to such repeated exposure. Away back in those early days

he had many strange experiences. The “grog boss” at sales, as at

loggings, was, next to the auctioneer, the most important functionary.

His duties were considered very important, and were sometimes far

reaching in their effects. Not a few of the old settlers who have had to

leave the township attribute the first cause of their trouble to too

close an acquaintance with the “grog boss.” Sometimes the result of this

officer’s operations took a ludicrous turn. On one occasion, when

selling in the township of Blanshard, a certain agriculturist of the

municipality had renewed his acquaintance with a dispenser of the “ two

forty ” so frequently that he found it necessary for his comfort to take

a horizontal position beside a straw stack for a short period of

quietness and repose. From the result of an accident this tiller of the

soil had lost one of his legs; but some local artist had supplied him

with another made of good sound timber, the growth of Canadian soil. A

dispute between some of the bidders culminated, as they often did in

those early days, in a free fight. The tussle continued for a minute or

two with varying success among the combatants. One of the belligerents,

who was a strong believer in potentialities, seeing what he thought was

a stout cudgel lying among the straw, grasped the wooden leg of the

sleeping farmer and tore it from its moorings. With this weapon he

entered the fray and dispensed his favors with a fearless impartiality

which indicated that he was no respecter of persons. The sleeping farmer

at last, from the noise of the affair, awoke, and trying to regain the

perpendicular, found that one of his legs was doing duty in some other

sphere of usefulness than the one designed by the maker. A volley of

unearthly yells, coupled with a broadside of language considered not

gentlemanly, excited the risibility of the crowd to such an extent that

order and the leg were both restored, and the sale proceeded.

At the separation of

the township of Blanshard from the township of Downie and the

introduction of the new Municipal Act, Mr. Dinsmore was soon called to

take an active part in political affairs. In the year 1855 he

accordingly became a candidate for municipal honors, and was elected as

councillor lor the division in which he resided. This was his first

attempt at public business as a representative of the people. He held

his seat at the Board as councillor uninteruptedly for several years,

being elected deputy reeve, and finally was honored with the chair of

the first officer of the township. Like all public men, his success did

not run in one straight and unobstructed stream. He had many

difficulties to face and overcome. Misrepresentation, the jealousy of

his rivals, and those who had once been liis equals but were now falling

far in the rear, were sometimes more than a match for his energy and

shrewdness. He suffered defeat more than once, but defeat to him meant

an expansion of his energies. He was irrepressible. All the calumnies

circulated against him by his political enemies had no effect on his

conduct. Like a trained fighter, no mat-how hard he was struck, when

time was called he was up in his corner and ready to give or take a

knock down in the next round. During all these years his financial

condition was still improving. He had erected a brick building that was

then and for many years after, the only brick building in that part of

the country. He had attained to a comfortable condition in a very short

time. The forest had been cleared away, roads had been made, schools had

been built, and the settlement on the tenth concession of Blanshard was

fast taking on the appearance of comfort and affluence which

characterizes it at the present time. At the election of 1869, Mr.

Dinsmore and Mr. Cathcart took the field against each other for the

reeve’s chair. They were by far the most prominent as well as the most

popular men in the municipality, and as might be expected, the contest

was a keen one. The question at issue was not one of personal fitness

for the honor, but a great principle was at stake between the

candidates, and which the electors were called upon to decide. Meetings

were held in various parts of the township, where the several questions

at issue were discussed among the people. The great principle the

ratepayers were asked to pronounce upon by their votes was whether the

toll gates should be removed and the roads made free, or whether the old

system of gates should be retained. Mr. Dinsmore advocated the old

system; Mr. Cathcart supported and led the abolition party. The causes

which led up to this contest I need not enter upon here. They will be

found fully explained in the sketch of Mr. Cathcart already before the

public. Mr. Dinsmore and his friends on this occasion were routed,

horse, foot, and artillery, and Mr. Cathcart gained the greatest victory

of his whole career as a public man. But this victory of Mr. Cathcart

led to another a few years later for Mr. Dinsmore and his friends, of

which no one on either side at that time could ever have had the

remotest idea. After being defeated he remained in private life till

1874, when he was again elected to the reeve’s chair. During this year a

rather ludicrous incident occurred at the Board, which will bear

repeating as an indication of the qualification of some of our leading

men of that day. The Ontario Government had passed an Act in the

previous session to enable rural municipalities to place a tax on dogs,

for the purpose of creating a fund which was to be applied for the

payment of sheep killed by predatory canines. This law in itself was

excellent, but like a great deal of such legislature, though good in

theory, it did not work well in practice. Designing men that had an old

croak sheep on the farm were always unfortunate (or fortunate) in having

their flock decimated by fierce canines, but by some strange coincidence

or other it was always the most ancient ones of the flock that were

destroyed. Thus the real result of the Act was to create a market for

much of the venerable stock of this class in the township. Another law

was finally passed compelling all applicants under the Act to make

affidavit before a magistrate that the claim was just and true in every

particular. At one of the meetings of the Board an applicant under the

Act presented a claim, but as no affidavit was attached, Mr. Dinsmore

instructed the claimant to see a worthy dispenser of justice who lived

close to the council room, and comply with the requirements of the law

before his claim could be paid. The claimant, having gone to the

magistrate, soon returned and presented the reeve with a piece of paper,

which he examined carefully and handed it without remark to the next

legislator on his left; and so it passed around the table amongst the

members of the Board till it reached the clerk. This officer was

supposed to be able to decipher the caligraphy of all correspondents,

and his achievements in this line had often been considered by the

township fathers as partaking of the marvellous. He examined the

document closely, and being somewhat of a literary turn of mind, gave

vent to his feelings in a quotation from Tony Foster, “It’s a d-cramp

piece of penmanship.” This was the signal for a burst of laughter from

the whole Board. None of them had been able to read the precious

affidavit. One of the members affirmed that ink must have been spilled

on the paper. The reeve declared it was a map of the Sandwich Islands.

Another said it was like the tactics of his opponent at the last

contest, fearfully dark, and past finding out. At last a Daniel came to

judgment in the person of the worthy magistrate himself, who informed

the assembled wisdom at the table that his pen was bad, and he sadly out

of practice, and lor fear that they might not exactly understand it, “he

had come himself to tell by word of mouth what the paper contained.”

ST. MARYS MARKET FEES

We must now give the

history of a transaction successfully carried out by Mr. Dinsmore, which

was the most important and far-reaching in its effects of any piece of

legislation ever transacted in the township of Blanshard. It has been

stated elsewhere that the toll-gates had been abolished in the township,

at great cost to the municipality, and the splendid roads leading

everywhere made free to all. From the period that a market building was

erected in St. Marys, the Town Council had from time to time passed

by-laws levying certain fees on all the products of the farm sold

anywhere within town limits. If a farmer sold a bag of wheat he paid ten

cents. If his wife or daughter had a dozen of eggs or a pound of butter

in her basket, she had to contribute a few cents to the town treasurer.

Failure to comply with the bylaw always led to a prompt interview with

the mayor, which usually ended by augmenting the town finances and

depleting the wallet of the agriculturist by a corresponding amount. It

is true that the corporation graciously granted the vendors from the

country the privilege of exposing their wares in the filthy old rookery

dignified by the name of the market building. The farmer’s wife was bold

indeed who could enter the doors of a place the air of which was

redolent with the effluvia of the fertilizing particles which adhered to

the decaying hides which were usually lying promiscuously here and there

in its dirty chambers. Her only alternative was to remain outside in the

summer heat or winter cold; but in either case the town got its toll.

Since the township had given free roads to every person who chose to use

them, the representative of the township had made repeated efforts to

have these obnoxious imposts removed, but without effect. At a meeting

of farmers belonging to a certain association, three delegates were

appointed to interview a committee of the town council for the purpose

of coming to some agreement whereby the objectionable by-laws would be

repealed. As might be expected, the town felt quite secure, and the

committee of the council simply ignored the Blanshard delegates. But a

solution of the difficulty was close at hand, and such a solution as no

one ever expected. The action of Mr. Cathcart some years before in

buying the gravel road leading into St. Marys was made the lever to

solve the problem. An officer of the municipality, in a private

conversation with Mr. Dinsmore, suggested the coercive measure of

placing a toll-gate on the main road leading into St. Marys, which would

have the effect of shutting off a large amount of the trade going to the

town, and of course injure the interests of the citizens.

Mr. Dinsmore at once

saw the opportunity and adopted the idea. When Mr. Cathcart bought the

road he simply bought up the stock at sixty per cent, of the face value

of the shares. He never surrendered the charter of the old company, and

by retaining that right made the township of Blanshard the sole owners

of the road. This action saved the whole scheme. After the toll-gate had

been erected an action was attempted against the township by the town to

compel the removal of the gate. It was held that according to the

Municipal Act no township had the right to impose imposts of that kind.

It was shown, however, that the township did not erect the toll under

any right it might have under the Municipal Act, but by the rights given

by the charter of the London and Proof Line Boad Company, which company

was now the township of Blanshard. This move, therefore, completely

collapsed. The policy of placing a toll on this road, although very

generally accepted by the people of Blanshard, met with a good deal of

opposition in some sections. The members of the council were not by any

means unanimous in the matter, two of the number being opposed to the

movement. To the honor of James Dinsmore, William McCullough, and James

Spearin, the two last of whom have passed away, they stood their ground

like heroes, until the difficulty was settled to the entire satisfaction

of both the municipalities. The St. Marys people did not yield without a

struggle. The gate was kept on for two years and rented for a third,

when one afternoon, to the inexpressible delight of the three gentlemen

I have named, Mr. E. W. Harding, who, I think, was mayor of St. Marys at

the time, came into the council hall at Blanshard, prepared to settle

the dispute. Mr. Harding had urged a settlement during the whole time of

the difficulty, buthad not been able to accomplish much, until a falling

off in the business of the town touched the pockets of his constituents.

A better man could not have been chosen to represent the town than Mr.

Harding, and before he returned that evening the whole matter was

arranged, and the lease of the toll-gate cancelled. During these two

years the gate had been profitable to the people of Blanshard. A check

was issued to every ratepayer, upon the presentation of which to the

toll-keeper he was allowed to pass free. All outsiders had to pay. Thus

the $1,200 which the township received for the two years they kept the

gate was contributed by the, adjoining municipalities, and relieved the

Blanshard ratepayer to a corresponding amount in his taxes. This little

episode between St. Marys and Blanshard brought the market fee question

so prominently before the people of Western Canada that the legislature

of Ontario abolished forever this vexatious tax.

HIS LATER YEARS

Mr. Dinsmore then

retired from the council, having sat as reeve at this time for two

years. On the 27th day of March, 1876, was organized the Blanshard

Mutual Fire Insurance Co., on whose board of directors was Mr. Dinsmore,

and which position he has retained, with the exception of one or two

years, ever since. In 1885, if I remember right, he was again a

candidate for the reeve’s chair, his opponent being Wm. Hutchings, whom

he defeated. He held the reeveship on this occasion for two years, when

he retired. This was his last appearance on the political stage of the

municipality, having been in the harness almost continually from 1853 up

to 1887, a period of thirty-four years.

We must now draw this

imperfect biography to a close. Mr. Dinsmore, at the age of

seventy-eight, is still strong and hearty. At his best he was never

robust looking, but his muscles seemed like wires of steel. He was

scarcely ever fatigued. Prolonged or severe labor affected him but

little, and he had his share of both. In all his business relations he

was prompt and strictly honorable. No man, during his whole career as an

auctioneer, could ever accuse him of favoritism or dishonorable conduct.

In the making of his accounts he rarely made mistakes, and he had to

settle the whole transactions of a sale, amounting to hundreds of

dollars, sometimes under the greatest annoyance. He knew men well and

could not be imposed on. For a person naturally impetuous and energetic,

all his business was transacted with coolness and calm deliberation. He

had a wide circle of acquaintances, and as matter of course received

many visitors, all of whom he entertained most hospitably. His

independence was one of the strongest features in his character. He

never decided a question, or was biased in any way, by the opinions of

other men, no matter what may have been their standing in society; be

they prophets, priests, or kings, all were alike to him. Men stood high

or low in his estimation on the same grade as their manhood. Under the

greatest provocation he preserved his equanimity. There appeared to be

no excitable qualities in his nature that could be touched by the vilest

asperities of his traducers. This was one of the factors that gave him

power.

He was Conservative in

politics, but not intolerant. The democratic feeling which was strong in

his nature had a subduing effect on his political thought; so much so

that he would never sacrifice what he believed to be the interests of

his country to any particular exigency arising in his party. He was

strongly attached to his family and to his home, and would endure great

hardship that they might be comfortable and happy. But to say that this

man had no faults would be to say that he was more than human. He had

faults and many great defects indeed. But his defects reacted upon

himself rather than on those around him. We conceive, however, it is no

part of the biographer to array the weak points of prominent men before

the public eye. Nay, we rather conceive that the duty of the biographer

is to place before his readers the good, the noble, and the true, that

those coming after may take pattern by their conduct, and emulate their

virtues. |