|

There was a fire just up the road from

where I am staying

This was a day trip to the island

where all the immigrants had to go through health checks before

being let into Quebec and Canada. It was actually a very thorough

process and I'd highly recommend taking this trip.

Found an old book discussing the island

which is in pdf format and can be read here

This is us going up the St. Lawrence

to immigration island

Here you are met by a tour guide who

will spend the next four hours with you taking you around and

explaining the process. You need to take a picnic lunch with you.

On the right is Sandy MacKay with his

daughter Kim

Canada’s Ellis Island

Penelope Johnston explores the tragic

legacy of Grosse Île, Quebec’s former immigrant quarantine station.

Written by Penelope Johnston — Posted September 6, 2016

As our boat nears Grosse Île, it feels

as though we are sailing back in time. The island — actually one of

twenty-one islands in the Iles-aux-Grues archipelago of the St.

Lawrence River — looms before us, a lonely place that’s haunted by

the memories of past tragedy.

Now home to a National Historic Site, the island seems so out of

place compared to the cheerful joie de vivre of nearby Quebec City.

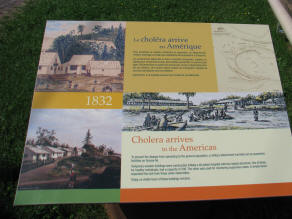

It was here, in 1832, that soldiers hastily erected tents, sheds,

and a forty-eight-bed hospital to fight the Asiatic cholera epidemic

brought by immigrants to these shores.

Some, like tourist Robert Henry of Toronto, are going to the island

in search of their own past. Between 1832 and 1937, tens of

thousands of Irish immigrants passed through Grosse Île in search of

a better life in Canada.

Among them were Henry’s Irish ancestors, who were forced to

disembark at the Grosse Île quarantine station before heading on to

their main port of call, Quebec City.

“We have two relatives that passed through in 1837 — Samuel Henry

and Ernest Dempsey,” Henry says. “One settled in Ontario and the

other settled in Quebec.”

At the pier, we’re greeted by Israel Gamache, a Parks Canada

representative who leads us on a walking tour of the west side of

the island, where the healthy were quarantined.

We pass a grey wooden wash house, where officials first attempted to

disinfect newcomers. It’s an eerie sight, and one can almost picture

crowds of anxious immigrants lining up for their turn at

disinfection.

A little further, we pass a series of hotels built from 1892 to 1914

to house, respectively, the healthy first-, second-, and third-class

passengers waiting in quarantine.

We start to climb over rocks, heading ever higher, passing trees and

stunted bushes to the highest point on the island. At the top stands

a fifteen-metre-high Celtic cross, which is cut from stone quarried

at Beebe, Quebec.

Built in 1909, it stands as a memorial to the Irish immigrants who

died of typhus here in 1847 and 1848.

Their tragic tale is written here in English, French, and Gaelic.

But it is only when we pass through dense undergrowth and down a

hill to a grassy field that the enormity of the tragedy is made

clear.

Driven out of Ireland by famine, waves of people left their country

in a desperate search for a home in the New World.

The influx reached its height in 1847, when in a single season more

than 100,000 Irish arrived at Grosse Île. Starving and malnourished,

the newcomers had little immunity to the typhus that ran rampant on

the ships carrying them across the Atlantic. In overcrowded and

unsanitary conditions on board sailing ships, five thousand Irish

perished of typhus at sea. Another 3,226 died in the hospitals on

Grosse Île. As many as sixty people per day were buried here at the

height of the outbreak.

Today, rows of white crosses mark the human toll. Nearby, a monument

tells the story of five physicians who lost their lives that summer

as they tended to the sick and dying. Among them was a Dr. Benson of

Dublin — only twenty-two years old — who died eight days after his

arrival. As we walk, some visitors take time to read a glass

memorial that lists the names of those who perished.

We cross a grassy field, heading for the trolley that will take us

along a narrow strip of land, past Cholera Bay, and into the central

section of the island, home to a small village.

On the far eastern side of the island is the Lazaretto, built in

1847 as the last of twelve original sheds used to house healthy

visitors, but converted into a hospital in 1848 and then used

primarily to treat smallpox. Scrawled on the walls are writings by

the patients.

The north section of the island is a bird and wildlife refuge area,

with more than twenty-one species of rare plants and over two

hundred species of birds thriving in the marshes and forests. Beware

of poison ivy.

By the 1880s, health care for the immigrants began to improve,

thanks to advancements in the understanding of diseases and their

treatments. At the harbour, a brass plaque sits in a red, barn-like

disinfection building, which was built in 1892. The plaque honours

the efforts of Dr. Frederick Montizambert, Grosse Île’s former chief

medical officer, who led many health-care initiatives that helped

reduce the death toll. Grosse Île ceased operation in 1937.

Odette Allaire, a Parks Canada spokesperson, says every Canadian

should visit Grosse Île at least once in their lifetime.

“The Americans have Ellis Island,” she says. “We have Grosse Île.” |