|

Ottawa Government and

Toronto—Industries—Institutions and factories—Adoption of English

customs—Aggressive commercialism—Fruit growing—Through Norfolk County—

Comparison with English fruit growing—Fruit preserving— Cost of labour—Bees—Poultry—Cheese—Bass

fishing on Lake Erie—Rods and tackle—Niagara Falls—Gifts to Manitou— A

great national utility—The mines of Ontario—Official returns—Sudbury,

Cobalt, and Porcupine—Encouragement and warnings.

OTTAWA, the seat of the

Dominion Government is situated on the banks of the Ottawa River, and on

the boundary line between Quebec and Ontario. The Upper House or Senate,

is composed of members, elected for life, having a property

qualification, and not under 30 years of age.

The House of Commons,

the Second Chamber, is elected every five years or at dissolution of the

Government in power. There is no property qualification, but only

British subjects are eligible. The members of both houses receive £200

per session with travelling expenses, and all polling at general

elections takes place on the same day.

The society of Ottawa

is chiefly of the official order, but the flourishing timber traffic and

other interests have established a large industrial community there.

Ottawa does not owe its

position as the seat of the Government and the capital of the Dominion

to its population, which only numbers 88,737. It is, however, making

marked strides in progress, and is annually justifying the distinction

it enjoys as the premier city. Its imports and exports, according to the

returns for 1910, amounted to £1,800,000; its postal revenue to £40,000

and its Clearing House returns, a sure symptom of progress, to

£34,600,000. The city assessment reached £10,101,641. Ottawa possesses

the advantage of enormous water-power. Within a forty-five mile radius,

this is said to equal 900,000 horse-power. The erection of new

Government buildings, palatial hotels, and the laying out and

improvement of public parks and drives, are in harmony with a city that

is rapidly developing, not only in commercial importance, but as an

artistic and literary centre.

There are already ten

railways running into the city, and three more are under construction.

Toronto, the Queen

City, is reached from Montreal in a night’s journey. It has no Mount

Royal, which commands such a fine panoramic view. On the other hand, it

is not an island, and has the possibilities of expansion to an unlimited

degree. Its growth in population has been rapid, doubling the number

each census. In 1889 it was estimated at 170,000; the last 1910 returns

show a leap to 402,567. Its assessment is £61,829,410. It is the seat of

the Ontario Government, the buildings of which are undergoing the

process of enlargement to meet the demands of increasing departments.

Toronto has a university of over 4000 students, and the industries it

fosters are many and varied, including 978 factories, which give

employment to over 75,000 hands. It leans towards English customs and

habits in as pronounced a degree as Quebec gravitates towards French.

Religious life is typified in handsome architectural edifices

representative of all the denominations. Its commercial enterprise

effectually detracts from its beauty as a city. Its streets are

interlaced with trams and railway lines, and its sky almost blocked out

with towering stores, and a tangled network of electric wires. The

facilities for getting about are a set-off against this unaesthetic and

undiscriminating commercialism. Tram-cars ply to and from the suburbs,

where primitive conditions are still preserved in park and stream and

rural charm.

Toronto is situated on

Lake Ontario. The belt of land stretching along the north shore is one

of the chief fruit-growing districts of Canada. The effect of this

beautiful inland sea is to modify the summer heat, and temper the winter

cold, and so exercise a beneficial influence on the soil. It is almost

impossible to realize that about fifty years back this fertile track,

sweetened with snowy blossoms in springtime, and rosy luscious fruit in

autumn, was entirely forest and impassable with the exception of an

occasional trail. Within a few hours’ journey from Toronto, orchard

farming offers good openings to small capitalists, and a training ground

for those who must wait a few years before starting on their own

account. Norfolk County, Ontario, is typical. It has many features akin

to the English landscape. Hill and dale alternate, well-cultivated

farms, in which the thickly set sheaves of corn stand, attest the

bountifulness of the harvest. Herds of sleek cattle and flocks of sheep

line up by the palings, as if not sure yet what sinister intent the

great snorting unclassified animal has on their pastoral peace. Were it

not for the palings, those inseparable concomitants of pioneer

agriculture, one might imagine himself in the Motherland. Nothing but a

green hedge is needed to complete the illusion.

Further on in the

journey a broad river, moving with a sedateness suggestive of depth,

rolls down the valley, deepening the green on its banks, and carrying

irrigation to the low-lying plains. The great rivers of Canada have an

economic value of incalculable worth to a land where summer sun is

rarely clouded.

The orchard district of

Norfolk County offers to the settlers land already cleared of the bush.

The long and tedious process of cutting, burning, and blasting, is

dispensed with, and the harvest return is not long deferred. A member of

the Provincial Parliament, and an expert in this department of

agriculture, took me over a couple of these farms. He had recently

visited our own country, and was therefore in a position to make

comparisons, and of quite an unprejudiced nature. He had gone through

Kent, and was struck with the high rentals that obtained there. They

were prohibitive compared with Ontario. A freehold farm of fifty acres

was offered in Norfolk County for £200. One grower raised from an

orchard of eight acres £518 worth of apples, giving a profit of £203

after paying all expenses. Another realized a profit of £89 from three

acres. Much, of course) depends on the age of the trees. Mr. E. D.

Smith, President of the Provincial Fruit Growers’ Association, states in

the report of 1910 that in Ontario there are 7,000,000 apple trees,

which should, at the lowest, yield 7,000,000 barrels of the best quality

of fruit in addition to inferior sorts.

Large quantities of

“culls”—apples too small to peel—are dried and shipped to France and

Germany for jam and cider.

Peaches are abundant

throughout Ontario, particularly in the Niagara Valley, which is

specially adapted to their cultivation. They also flourish north of Lake

Erie, where I saw trees, laden with them. An interesting experiment was

successfully carried through whilst I was in the Dominion. A consignment

of peaches was shipped from Ontario to a London fruiterer, which,

according to a cablegram, arrived in excellent condition. This was

regarded as a first step to supplying the London markets with this

choice fruit.

In Prince Edward County

the tomato in particular is cultivated. It grows in the open and the

yield is good; 500 bushels to an acre is an average crop. Fruit produce

is extensively preserved in Canada, and widely shipped. Forty-eight

million pounds are annually packed in this form. I visited one of these

canneries on the shores of Lake Erie. There they pack 50,000,000 cans a

year. The expense of labour is considerably reduced by using natural gas

for their machinery. An engine of eighty-five horse-power can be run at

a cost of 55. 3d. a day. The gas was lit in the town through which we

drove; this seemed singular in the full light of day. The explanation

was plausible: it was cheaper to keep the gas burning than pay a man to

go round and turn it off.

That Lilliputian but

indefatigable farm labourer, the bee, realizes the ideal conditions of

getting and giving. Some farmers keep them for fructifying their

blossom, and use the honey as a by-product. As an industry in itself,

bee farming is becoming popular, and commands an extensive market.

With regard to

fowl-keeping one might describe poultry, figuratively as well as

literally, as running alone. Hens are no expense, as they cater for

themselves. Chickens and turkeys are more generally raised than ducks

and geese. In eastern Ontario dairying is the chief farming industry.

The British Isles are a market for the produce. The factories for cheese

and butter are for the most part co-operative. Hastings County alone

sends £400,000 worth of cheese annually to the Mother Country. The

combined output in Ontario is £3,000,000 yearly. The co-operative system

is said to be an advantage to the small farmer, who no longer has to

bear all the expense and risks and find his own market. He only has to

send the milk to the factory to be churned into dollars.

Cheese-making as an art

is taught at the Macdonald College, I saw Stilton and Cheddar specimens

in no way differing in quality from their English ancestors. The breed

of milch cows in Ontario is receiving great attention.

It was only a short run

from the fruit fields of Norfolk County to the black bass waters of Lake

Erie. Mr. Pratt, being a Waltonian, cheerfully accompanied me.

We were fortunate in

having as our companion Professor Navitz, a government expert on

forestry. We all shared the hospitality of Dr. Mclnnes, a sportsman to

the manner born. He is a veteran in years but a youth in spirit, with

the Scotch mother-tongue still triumphant, despite long residence in the

Dominion. He lives on the lake shore, and at 6 a.m. we fortified

ourselves for the expedition with a substantial breakfast, in which ham

of suspiciously York flavour formed the pike de resistance. Long before

the first fierce rays of the sun struck the lake we were far from the

shore in a motor boat, the doctor’s fine baritone ringing out cheerily

at the jokes and bons mots that garnished the feast of reason and the

flow of soul. We had a distance of twelve miles to travel before the

fishing ground would be reached. It lay off the point of an island far

away on the horizon. A couple of buoy like marks on the water showed

that other anglers were already on the spot. Four miles off St. Williams

lay White Fish Bar, where the doctor had one of those much-coveted Lake

Erie shootings. A wood duck, winging its flight across the water, led to

a discussion on the merits of the sport it gave. Red head, canvas-backs,

black duck, pintails, teal and mallard, the latter a distinct species,

would visit the place with the first snap of cold, and as many as thirty

to forty brace would be bagged in a day’s shooting. These hardy birds

travel at a great pace, and are as difficult to stop as driven partridge

with a gale of wind behind them. Taking one shot on the approach, they

will be out of range of the second barrel on wheeling round. The islands

that afford such sport consist of a good deal of marsh land, where wild

rice grows, on which swan and duck flourish. The Government charge high

fees for shooting.

Long Point, standing

away on the north-west, commands £2000 per gun for a life interest, and

a select club of sixteen holds the monopoly. The island is twenty-one

miles long, and three wide. It is well wooded in places, and in addition

to other game there are two or three thousand deer.

Bass, like trout, take

to the deeper parts of the lake during July and August. In the spring

they are found on the shallows, where they rise to the fly, and take a

silver doctor, a Jock Scot or a dusty miller. Minnows, which abound in

Lake Erie, as well as perch fry, demoralize the bass as they do trout in

Irish lakes. When they begin to gorge on these, flies dance over them in

vain. Their cannibal tastes had to be studied, and we netted a bucket

full of these small fry before starting. They are mounted on a gut trace

with a single hook attached, and a sinker sufficient in weight to carry

the line within a foot of the bottom. Canadians use short steel rods, a

multiplying reel, and stout tackle.

The outfit scarcely

commends itself to a scientific angler. The gut is strong enough to play

a salmon, and the rod is stiff and only from four to six feet long.

Steel does not possess the flexibility of split cane or greenheart. A

multiplying reel seems to me both clumsy and unnecessary, and is mainly

fruitful in multiplying the angler’s sorrows. The object—the rapid

recovery of the line—is scarcely needed in the case of bass. The fish do

not take long runs like salmon or trout, but bore like the grayling,

making the best use of the large dorsal fin. The tax on the spare line

is slight. I have had many a bold run from trout and salmon, which

nearly emptied the reel, but I have no recollection of any difficulty in

recovering the slack on the fish’s return journey. The immediate effect

of the weight of a fish on a multiplying reel is a tension, which makes

winding impossible. This is due to the complication of wheels within

wheels, and the locking of the cogs. The only way to recover the line is

by rapidly lowering the rod, when the winch can be worked freely enough.

This process is repeated, until the needed quantity is recovered.

Anglers will, I think, agree with me that to give a fish a slack line

runs the risk of giving him his liberty. I have known trout and salmon

that only needed a moment’s slack to get rid of the hook effectively. If

a fish is firmly hooked it does not matter; but how often does the fly

drop from the mouth of the trout and salmon the moment they are netted 1

Had the slack been given before netting, they would have escaped.

No doubt the strength

of the tackle which the Canadians use enables them to give the bass

rough handling. With fine gut, a stiff rod and an unyielding reel could

scarcely be used without losing many fish. I think it is possible that

the time will come when coarse tackle will affect the weight of the

creel.

Bass are at present

unsophisticated, and therefore bold feeders; but so were trout in our

English waters years ago. Meanwhile they have become educated, and the

greatest wiles have to be practised to lure them. Nothing but the finest

drawn gut is used on many chalk streams, where once rough tackle made

heavy baskets. Bass can be educated too, and I found lakes, where once

they fed freely, which barely yielded a brace per diem. It may be that

the stock is depleted. With the causes of that I shall fully deal later

on.

In discoloured water on

a dark day the nature of the tackle is not of so much moment. But in

water crystal in its purity, with the bright Canadian sun added, coarse

tackle is likely to reduce the take.

An ideal rod for black

bass is a ten-feet split cane fly pattern. This yields to all their

movements, and finer gut may be mounted. My outfit consisted of a Hardy

Brothers’ “Houghton,” and “Perfection” reel. I lost only a small

proportion of the fish hooked, and had no smashes, although I used

nothing stronger than a refin trout gut. With this outfit I believe I

had the maximum amount of sport these gamey fish afford. A pike, after a

bold dash, cut the gut, but that is a contingency likely to arise where

one does not use gimp. The take for the day, with a quartette of rods,

included thirty-nine black bass, largest, 2½lb.; one rock bass, ½lb.;

one sheep’s head, 2½lb.; three wall-eyed pike, largest 4lb. We only kept

the regulation number; the surplus were returned, with a host of smaller

fish not included in the list. Mr. C. S. Williams, proprietor of Lake

View Hotel at Long Point St. Williams, supplies motors and angling

requisites.

The delightful day on

Lake Erie all too soon came to a close. As the motor boat raised her

anchor a magnificent sunset lit up the western sky. The water was so

smooth that the effect was mirrored in an unwavering reflection. No pen

could describe nor brush portray the richness of the carmine or the

delicacy of the blue that lit the heavens. Canadian sunsets are

unsurpassed. As we neared the shore the light was rapidly waning and the

distant woodland already veiled in darkness. We passed a lotus bed near

enough to see the plant’s broad leaves closing for the night. It is said

to be one of the three that exist outside Egypt. There is little

twilight in the Far West, and by the time we reached the landing stage

night had fallen. Everywhere there was stillness except on the borders

of the wood, where the exquisite notes of the vesper sparrow rang out

with a richness of song equalled only by the nightingale.

Lake Erie is the

head-waters of the greatest natural phenomenon on the American

continent— the Falls of Niagara. Out of its great expanse of water the

river flows that plunges across the chasm, and silently sinks into Lake

Ontario with no sign of its adventurous journey save a foam-streaked

surface.

I took the first

opportunity of re-visiting Niagara. More than a score of years ago,

during a holiday in the United States, I saw the magnificent spectacle

for the first time. The setting of the Falls had undergone some change

meanwhile. A bridge linked Goat Island with the mainland, and commercial

obtrusiveness along the shores had left its desecrating marks in huge

and unsightly buildings.

But the Falls, ah !

nothing could spoil them. The deep diapason of their roar had not grown

less. The myriads of crystals, dazzling in their brightness, still

rolled over the precipice and thundered into the yawning abyss, ever

athirst with insatiable greed. The mist still veiled the cataract, and

the spray bow formed its complete circle; no segment this, but an

infinite round, in keeping with infinite marvel.

I walked through the

Cave of the Winds, and heard the shrieking as of ten thousand fiends,

and was whipped with the water lashes of offended spirits. I watched the

rapids below the Falls, seething and foaming as if the water had grown

mad, with the great leap across the precipice. The power that lies

hidden in this world’s wonder has made its appeal alike to superstition

and science, in the one case working tragedy, in the other utility. We

see the young Indian girl set adrift in her canoe, laden with fruit and

flowers, and swept across the Falls, the annual offering to the great

Manitou, which troubled the waters and exacted such toll from mortals.

One recalls the case of the Bristol youth who fell beneath the river’s

spell, sold his property, and became the hermit of Goat Island; and

there, ever with the call of the wild in his ears, at last yielded to

the fascination and plunged into the maelstrom in obedience to the

behest of beckoning spirits. But other times, other manners; and to-day

the power of Niagara has been converted into a public utility, and the

great spirit, once the despotic master, has become a docile servant. It

may spoil the romance to learn that the tram-cars of Toronto and

Windsor, the latter 120 miles distant, are hitched to the Falls. Such is

the latest adaptation of waterpower to municipal needs.

The eye of the

appraiser has looked upon the river and read in it a value for national

purposes of £400,000,000. Science has measured its flow, and averaged it

at 75,000,000 gallons per minute. Engineering has converted the figures

into dynamics, and made them stand for 6,000,000 horse-power.

It is scarcely a matter

for wonder that commercial enterprise should seek to utilize so mighty a

force when we learn that it is equivalent to the aggregate power of all

the steam engines and boilers in the United Kingdom.

Once more let us turn

our eyes on the Great Falls, and cancelling the dollar aspect, try to

realize that the power embodied therein is capable of working to the

full every railway and factory in Great Britain and Ireland. At such a

moment one feels kinship with the simple-minded red Indian, and uncovers

his head and worships.

When the power of

Niagara is drafted into service, and fulfils a public utility, instead

of fostering a superstition, there is no need to quarrel with the new

point of view. The project, happily, has not been allowed to become a

vested interest and the monopoly of a private company. The Ontario

Government has guarded against that by taking the matter into their own

hands. The effect has been to cheapen the national cost of electricity,

house-lighting has been reduced 50 per cent., street lighting 31

percent., and motor-power 37.5 per cent.

The incidental

advantages of the water-power of Niagara are summarized in the Board of

Trade report:

“The employment of

electricity carries with it other advantages in addition to that of

cheaper power, and these are, in some cases, of greater importance.

“The use of electric

power for street railways and the consequent cheapness and increased

rapidity of transport has, by widening out the living radius,

contributed greatly to the comfort of the population, and diminished to

a considerable extent unhealthy crowding in city tenements.

“In the factories

themselves, the use of electric motors for driving electric machinery,

by doing away to a large extent with pulleys and counter shafts, has

made machine rooms healthier, cleaner, and better lighted.”

THE ERIK RIVER, NIAGARA RAPIDS

The mining industries

of Ontario for the most part are happily shorn of those sensational

elements which engender wild excitement and fevered expectation among

speculators and adventurers.

The traveller who

skirts the northern shores of Lakes Huron and Superior has little

conception of the hidden mineral wealth that lies beneath the hills

which the railways burrow. West and east, north and south, mines are

being discovered and worked. With better machinery and the application

of modern methods of engineering, the marketing of mineral wealth

becomes only a question of time.

The report of Mr.

Thomas W. Gibson, Deputy Minister of Mines shows the annual progress

made since 1903. The various products are valued as follows:—

1903 £3,570,859

1906 £4,477,676

1907 £5,003,874

1908 £5,127,523

1909 £6,596,273

As compared with 1908,

the year 1909 shows an advance of 28 per cent.

The nickel and copper

of Sudbury were the first to be developed in the province. In this

district the Canadian Copper Co., the Mond Nickel Co., the Dominion

Nickel Co., and the Helen Iron Mines are situated. The latter are the

largest shippers of ore.

To the same district

belong the Moose Mountain Iron Mines, where the process of treatment,

which is most interesting, may be seen. The ore is taken and reduced to

an inch product by crushing, after which the waste rock is separated by

a magnetic process. The ore is then placed in crushers and reduced to a

uniform size of less than an inch. It is then conveyed to the magnetic

concentrators by means of an inclined belt. Next it is shot into bins

which discharge their contents into magnetic separators, and finally

conveyed into the cars of the Canadian Northern Railway to be shipped.

About 800 tons per hour can be loaded.

Extensive iron deposits

have been discovered at Grand Rapids and Blairton, and marble and

graphite at Bancroft and Wilberforce, in the Hastings district.

Four of the iron mines

produced during 1909, ore to the extent of 119,207 tons, and the Helen

mine at the Sault yielded 112,246 tons. The returns from eight blast

furnaces were estimated at £1,395,483 worth of pig iron, and £1,571,081

worth of steel.

Cobalt is another

centre of great mining importance. Its chief output is silver, which

from 1904 has been a rapidly growing industry. The official returns

since that year are given at 93,977,833 oz. of silver, valued at

£9,665,456.

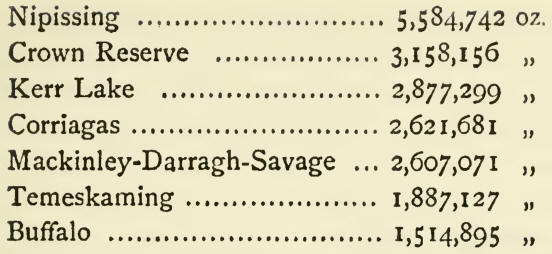

The chief Cobalt mines

and their output are as follows:—

In Cobalt and its

vicinity the production of silver in 1909 exceeded any previous year,

the total being 26,000,000 oz. The towns of Elk and Smith on the

Montreal River form the distributing centre of this area. There are

nearly 150 mines in the district. The Northern Customs Concentration Co.

is situated on the town site of Cobalt. It obtained the contract in 1910

for concentrating the mining ore of La Rose and City of Cobalt mines.

The process carried on here is both complicated and elaborate. The ore

goes through a crusher, and is reduced to a three-quarter inch product.

It is then subjected to several processes of separation, and ultimately

passed over canvas.

Mr. T. W. Gibson sums

up the industry in this district in the following words:—

“The seven years which

have elapsed since the opening of the mines of this remarkable camp have

been seven years of increasing plenty. The ratio of increase is now

lessening, and 1910 will not exhibit as great an advance over 1909 as

1909 did over 1908. Indeed, if no new and unexpected additions be made

to the known sources of production, it may well be that Cobalt has

reached or is approaching its climacteric, for it must not be forgotten

that a mining camp will not last for ever. The present rate of

production may, however, be maintained for some time to come, and

doubtless Cobalt will be producing silver a generation hence.”

Porcupine goldfields,

which attracted a good deal of attention recently, are situated in

Whitney and Tisdale, west of the recently opened Temeskaming and

Northern Ontario Railway, and near to Kelso on the Canadian Pacific.

In 1899 the region was

explored by Dr. W. A. Perks on the behalf of the Provincial Bureau of

Mines. He discovered gold widely distributed, whilst the region south of

the trail to Porcupine and other areas showed traces of the metal. With

the approach of the railway in 1907, there was a rush made by Victor

Mathison for Nighthawk Lake District. In 1909 John S. Wilson and a party

discovered Dome Mine, and from that centre a region of fifty miles

yielded gold, varying in grade to the prospector. A boom in speculation

followed. A letter to the “London Times” urged the investment of British

money in the enterprise.

A Glasgow firm sent out

a representative to investigate, with the result that the Scottish

Ontario Syndicate, was formed, and property was acquired. Other British

companies followed.

Expert opinion was

generally favourable to the new venture. Three thousand square miles

were prospected and over iooo claims staked. The speculative brokers

exploited the Press, and companies were formed without difficulty, on

the assurance that a northern El Dorado was discovered. “Chunks of

gold,” “Phenomenal finds,” “More gold in a single property in the

Porcupine than in the whole state of Nevada,” were the seductive

headings of articles and prospectuses.

Friendly caveats were

not wanting. A Scotch expert said, “Yes; there is gold, but Porcupine is

no poor man’s camp; much expensive machinery will be needed. If there

are millions in the ground, it will take millions to get them out.” Two

other opinions are worth quoting, Mr. H. E. T. Haultain, Professor of

Mining at Toronto University, said, “The good gold values were first

recognized about nine months ago, and one cannot form any definite

opinion as to the work accomplished in such a short time. Still, the

fact remained that while too early to be sure, the camp gives great

promise. Very many of the claims which have been recorded will

undoubtedly produce disappointment instead of gold. Many of them are

located on swamp ground, and many of them are claims staked when the

snow mantled the earth. Much quartz will be discovered that does not

carry commercial value. To sum up, after nine months’ life, the

Porcupine camp affords well-based hopes that it may become a valuable

gold-producing area, with greater permanence than has hitherto

characterized Ontario gold camps.”

The other opinion came

from Mr. R. W. Brock, Director of the Geological Survey, Ottawa.

“The district furnishes

remarkably tempting specimens. About 9000 claims have been staked, the

great majority of which have, of course, no real present or prospective

value as mines, but they are in Porcupine, and can be bought or sold.

But there are some really good-looking prospects. Quartz is remarkably

widespread over the district, and visible gold is abundant in some

showings, and has been found at numerous widely separated points. Most

of the gold occurrences so far located are in Tisdale township, but some

of the properties are in Whitney, others in Shaw, and in the Forest

Reserve. Porcupine is yet in the prospect stage, but it has some of the

essential qualities of a gold camp, sufficient to have induced

experienced men to take up options at high figures, and to undertake

large expenditures to determine if it possesses all the essential

factors.”

The Government attitude

on the subject was frankly expressed by Mr. Cochrane, Provincial

Minister of Mines, who visited Porcupine personally to investigate the

prospects. On his return he warned the Press that the Government were

determined to suppress “wild catting,” and make it unpleasant for

speculators. All dangerous or illegal statements in prospectuses would

come under strict surveillance, and closed this declaration in words

creditable to himself and the Government he represented:

“Ontario is in a fair

way to materially expand her development, and augment her resources as a

result of sound, prudent, and businesslike operations in the Porcupine

field. But if the Province is to secure the best results in every

direction, there must be wholehearted and determined co-operation on the

part of the Press and the Public to combat all wild-catting operations.”

There were 282 mining

companies incorporated under the laws of Ontario in 1909 with an

aggregate capital of £47,376,600. |