|

En route for French

River—Pickerel Landing—The house on the rock—Primitive simplicity—The

fate of the skunk—The Ojibwa Indian guide—Reversion to original

type—Whisky and deterioration—French River—Recollections of Champlain

—Trolling for bass and pike—A master of the knife—A fight with the

“tiger of the river”—Gaff versus rifle—The indefatigable guide—The might

have been—In camp—The note of the whipoorwill—“The fretful porcupine.”

THE Canadian Pacific

Railway has recently been extended to Sudbury, the centre of a large

mining industry. It has opened up a hitherto unexplored area of river

and forest. For fishing and shooting it is one of the best districts in

the Ontario Province. I travelled to Pickerel Landing which accurately

describes the situation. It is nothing more than a landing, with not

even a platform attached, to say nothing of a station. For primitive

simplicity and the complete negation of all luxuries it can scarcely be

surpassed. I scrambled out of the train, encumbered with fishing rods

and other impedimenta of the chase, and climbed down to the railway

track. Below it a magnificent river swept beneath the bridge, and in the

midst of the river there was an island with a wooden habitation perched

on a high rock. This was Wanikewin, or the “house on the rock.” To do it

full justice it was the hotel whose hospitality stood between me and

starvation, and destined to provide guide, canoe, and all the

paraphernalia of a camping outfit.

The moment the train

moved off on its northern journey, leaving my solitary figure in more

emphatic relief, a boat was pushed off the island, and the quick flash

of a paddle assured me that I had been discovered.

Wanikewin as an

achievement of civilization was only a degree removed from the general

desolation of the' place. It was a wooden structure, through which the

wind whistled all day, and at night the music incidental to somnolence

in one apartment could be heard in all the rest. The chance rambler

outside the precincts was by no means cut off from any advantage that

this primitiveness conferred. There was not a glass window in the house.

A mosquito net closely nailed to an opening did duty for that. It

succeeded in keeping out the winged pests, but not the rain, which

forced its way through the network during the night. So near was the

whole thing to the heart of nature, that the skunks claimed a right of

entrance, and had to be shot. A beautiful specimen underwent that fate

half an hour after my arrival, which insisted in making a storeroom a

nesting-place for her young.

If this description of

a hostel, which is not exaggerated, is likely to deter any sportsman

from going to Wanikewin, let me assure him that of the places that I

visited in the province, it was one of the most charming. The crude

structure possessed all the conveniences that an explorer might desire:

a postoffice for dispatch and delivery of letters; a store amply

provided with provisions; camping tents of the latest and most

comfortable design; canoes adapted to all the exigencies of the rivers;

Indian guides, true children of the wilds; and a motor boat to shoot up

the river and reach the nearest portage through the forest where human

footsteps were almost unknown.

It is because this

primitive simplicity is all too rapidly disappearing from Eastern

Canada, and the modern hotel is taking its place, that one involuntarily

exclaims, Oh, Wanikewin! keep thy wooden walls, thine unglazed windows,

thine odorous skunks, and untutored Indians, and we shall love thee all

the better!

It was something to be

handed over to the charge of an Indian with royal blood in his veins.

Ellick, my guide, had that particular distinction to commend him. His

father, a chief of the Ojibwa tribe, died twelve years ago. The

heir-presumptive to a disbanded kingdom possessed all the solemnity of a

fallen magnate. He would sit on a ledge of rock, and look out across the

surging river as if awaiting the summons to emancipate his tribe from

the thraldom of civilization. It was interesting to try and discover

what survived of the original qualities of the redskin. The preliminary

survey of dress was not encouraging. A pair of heelless boots and

patched nether garments, had little suggestive of the buckskin moccasins

and buffalo robes garnished with porcupine quills. An old planter’s hat

was a distant remove from the erstwhile conjure of golden eagles’

feathers.

But there was reversion

to original type despite this sartorial vandalism. The Ojibwa

temperament was there, and showed itself on the least provocation. The

pensive face, with beady lustreless eyes, became animated under

excitement. In motion there was a stealthiness in Ellick’s tread, which

pointed to an hereditary connexion with the chase, a grace of carriage

suggestive of nomadic ancestry. When the canoe silently drifted round a

bend in the river and surprised a buck slaking its thirst, the Indian’s

nostrils would quiver like those of a staghound held in leash, as the

quarry dashed into the forest.

The North American

Indians are now confined to Government reserves all over the Dominion,

where they follow pastoral pursuits and engage in different forms of

labour. They still shoot the deer, trap the beaver, net and spear the

salmon, and as these pursuits are regarded as essential for food, and

were enjoyed by them in practical monopoly, the Indians are granted a

great deal of licence, and the close season is not enforced. In their

unsophisticated primitiveness they make excellent guides, their

knowledge of rivers and forests being invaluable. Close contact with

civilization does not always improve them, and under indulgence they

grow indolent and inefficient. Their introduction to the bottle by the

white man has marked a stage in deterioration so distinct that it is now

a penal offence to give them ardent spirits. Unfortunately this law is

ignored by many sportsmen. On one river where they act as guides I heard

it said that the Indian will go as far as the whisky-bottle lasts.

Another deduction may be drawn from a saying, common in regard to them,

“The Indian who can speak the English language is a bad guide.” You are

frankly told that you must have ignorance or inefficiency. On the

occasions when I employed them, I found them both interesting and

efficient, and in two instances they could not speak English, beyond a

grunt meant for “yea” and a headshake for “no.”

Ellick was a case in

point. His gesticulations and the emphatic use he made of one or two

words, were eloquence in themselves, and his quickness in understanding

my wishes and complying with them left little to be desired.

When one remembers the

habits and customs of the race from which the Indian sprang, there is

little surprise at the great change that has taken place in his spirit

and temper. The wild child of Nature, unrestrained as the mountain

torrent; savage in instinct, with no law, but a law unto himself;

consigned to the rules and restrictions of modern civilization, as he

has been; is it any wonder that his nature should chafe and deteriorate?

The ample provision for his needs in itself made for deterioration. The

rifle in exchange for the bow, the shack for the wigwam, the purchase

power of money in store and saloon; all this, so contrary to the

environment of the rugged mountain, the entangled forest, and the

struggle for life they imposed, civilized the North American Indian, and

at the same time inaugurated the rapid extinction of the species.

A short portage brought

us to French River. It is high above the level of Pickerel and narrow

where it debouches into it, broadening out again as progress is made

up-stream. It probably differs little from the river which Champlain

descended two centuries ago. History records how he pressed his way

across land from Lake Nipissing and struck French River after exploring

the Ottawa. Working his way down-stream, he found a tribe of naked

Indians gathering berries on the island rocks. They were Ojibwas, the

tribe to which my guide belonged. With the exception of an occasional

trapper or lumberman, few Europeans have since shot its rapids or camped

on its banks.

As Ellick paddled the

canoe up-stream, I mounted two fishing-rods, one with a spoon bait, the

other with a Devon minnow, and began trolling. In a short time, several

small-mouthed bass were landed, the largest of which we kept. A reach of

the river fringed with weeds yielded a couple of wall-eyed pike, which

took eagerly, but were returned to the water as undersized. Mounting

larger spoons, two or three pound bass seized them, to the huge delight

of Ellick, who had probably never seen fish caught with anything more

scientific than a hand-line or spear.

The maskalonge is the

chief game of the French River. It closely resembles the pike in

appearance and habits. The shape of the head is flat and elongated, and

resembles that of the. Esox lucius, although larger in the mouth. Its

body is thinner in proportion to its size, and the fish is capable of

equally rapid motion through the water. The colouring is dusky grey,

with none of the bar or spot markings distinctive of the pike. Like the

latter, the maskalonge is predatory in its habits, a veritable

highwayman of the stream. On the margin of weeds it lurks, its colouring

matching the river flora, or contrasting in a way equally deceptive. It

is a master in the art of mimicry. The long, thin body changes in tint

with the variegation of the weeds. In the spring it is a lighter colour,

in keeping with the early verdure, becoming darker as the season

advances, and in the winter, when the weeds are dying off, there is

another change in consonance with its environment.

The maskalonge, like

the pike, has its special feeding times, and one may fish for days

without getting one of the large specimens, which gorge themselves and

lie up until hunger sends them on the warpath again.

It was August when I

fished for them, which is said to be one of the worst months for

angling. The current opinion amongst Canadians that the maskalonge shed

their teeth that month, is not generally supported by ichthyologists. It

is contended that the phenomenon has its analogy in the deer shedding

its antlers and the snake sloughing its skin. Fish, like grayling,

become very soft in the scales when out of season, and are in the habit

of casting them, but stiffen up again during the autumn months. Counter

arguments might be raised against all this. Very old fish lose their

teeth, no doubt, through senile decay, and possibly the discovery of

some toothless maskalonge has given currency to the belief.

Two or three times I

thought I had got hold of this tiger of the river, but the vigorous

plunge and bold dash was caused by a pike of more than average size.

Clearly, the maskalonge declined to be rushed, and we had to bide its

time. Meanwhile, Ellick paddled slowly and patiently up-stream.

The French River

broadened out to a mile in places, and disclosed magnificent bays

bordered with pines and tamaracks. Its course was a complete puzzle.

There were a number of these expansions in every reach, in places biting

into the forest for half a mile, then sweeping round overlapping

islands. It was a maze to all but the experienced boatman. I found

myself speculating on the true course amongst the openings, but

unsuccessfully. Sometimes it lay to the right, at others to the left, a

sharp turn here, a forward and back there. But Ellick never erred; true

as magnet to the pole, his native instinct guided him. Often I thought

he was caught napping, as we found ourselves in a cul de sac, but the

Indian had made a detour, and a big mellifluous voice, eloquent in the

Ojibwa tongue, would whisper, “Lunge,” “bazz,” softening the sibilant

into the music of the mother tongue. “Big rock-bazz,” and sure enough as

the spoon drew near to the granite cliffs the reel would scream, and

high out of the water the bass would spring, made captive by the bait.

Higher up the river,

the forest became less dense, and there were occasional clearings,

probably the effect of winter floods, where the river overflowed and

drowned the trees along its banks. In the background they showed again,

massed in unbroken phalanxes. Crowned with dwarf pines and poplars,

island rocks stood forth in midstream, their white quartz seams clearly

showing, and their fissures green with the seeds that had found foothold

there. An occasional Norwegian pine towered from the bare bank, proudly

proclaiming its victory over the flood that had swept away its less

hardy fellows. Its roots had struck too deeply to be moved by wind or

water.

We had luncheon on one

of the islands, where my Indian guide showed a rare genius in the

culinary art A few slashes of an old knife with a villainous look about

it suggestive of other uses, removed the backbone of a bass and

pickerel. The deftness of the strokes showed an inherited aptitude for

scalping, becoming the son of a chief. Soon the blue smoke of the

kindling logs rose from the island, and with it the odour of delicious

viands, bass, pickerel, tea, fruit. Here was ambrosia, the very food of

the gods waiting on little less than fiendish appetites. Oh, what a

luncheon!!

Towards evening I had

expectations of a fight with a maskalonge. We had caught bass,

smallmouthed and large-mouthed, and a rock species with little fight in

it compared with the others. But what a handsome fellow he was, with

deep blue eyes and carmine irises! A dorsal fin exceptionally large with

eleven rigid rays and eleven soft. Underneath there was a fin with six

rigid rays and eleven soft. Beneath the throat the pectoral fins met in

a fan-shape of artistic design, with five rigid rays in each. All these

trimmings surmounted by a head and body

of golden green. But

“handsome is as handsome does,” and the rock bass was a poor fighter.

The cook holds a different opinion of his merits, and not without good

reason.

The best pike, a fish

of 9^ lbs., took a fancy to a large spoon bait intended for his betters,

and gave the liveliest play so far. Then a long and uneventful paddle in

an atmosphere without a breath of air. There was a violet haze on the

water, and nothing broke the stillness of the smooth-flowing river but

the regular beat of the Indian’s paddle. The rods were set athwart the

canoe, a 3½ inch spoon on one and a large Devon minnow on the other. It

had been a long day, and as there is only one position possible in a

canoe, I was getting weary. The close atmosphere and the smell of the

pines began to have a soporific effect, and I closed my eyes. The swi—ish

. . . swi—ish, the regular beat of the paddle, grew fainter and fainter

. . . swi—ish . . . ish . . . oblivion.

“Lunge! lunge! ”

cur-r-r. These were the combined noises that awaked me, comprised of

Ellick’s loud cry of “Lunge!” and the crescendo scream of a 4-inch pike

reel revolving like mad. Far away, the line was cutting the water with a

hiss. There was no mistake this time—I was fast in a maskalonge. I

seized the rod, whilst Ellick reeled up the other to avoid entanglement.

The big spoon had done the business, seducing the tiger which had gone

forth on his evening prowl.

I had no fear of the

rod, which was a stout green-heart of carefully selected timber, and

specially made for large salmon. The line was finest silk, and the spoon

mounted on gimp that could not be readily cut with the fish’s formidable

teeth. It was a question, therefore, of firm hooking and careful

handling. The moment I applied pressure to check the run, the fish

turned and took a slanting direction. Ellick paddled towards him, and I

recovered about twenty yards of line. More pressure set him off again,

with a pace equal to a salmon’s, which ended with a break on the top of

the water, disclosing his full proportions to our admiring gaze. Another

pause followed, with more paddling and reel winding. So things

progressed for some time.

The maskalonge’s method

of fight is cunning. He makes rapid runs in the effort to break loose,

then rests almost on the top of the water. This gives him breathing

space, and when the canoe approaches him he is off again as vigorous as

ever. In this particular he differs from the salmon, which only comes to

the top when absolutely exhausted, excepting, of course, Salmosalar's

lordly springs. How far he might alter this method if played with a

hand-line, a method all too common in Canada, I do not know. It is

possible that the firm pressure of the rod brings him up. The spring

salmon of British Columbia keeps steadily on the move, with only an

occasional dash, and in that way reserves its strength. The maskalonge

exceeds pike and Canadian salmon in speed, but the runs are short. By

such a method the fight is much prolonged. My captive leaped out of the

water a couple of times, and acquitted himself in such sporting style

that I share the high opinion he has earned amongst anglers.

It is not easy to play

and land a fish from a canoe which is in danger of capsizing if there is

more smile on one side of the face than the other, so that when the

stage of exhaustion was reached, Ellick ran me ashore, and I gaffed the

prize. I did not call in the aid of a rifle or revolver to assist in the

process. Judging by angling literature and common report, this is the

usual method of putting an end to the maskalonge’s struggles. It is, to

say the least, a most reprehensible one, and those who practise it can

scarcely be regarded as true sportsmen. Angling is a pastime, and

regulated by reasonable rules. To supplement a rod by the aid of a rifle

is not playing the game ; it is only using dynamite in another form.

My captive was over 10

lbs. weight, small, no doubt, compared with the monsters to be met with

at times, but he was a fair sample of the species, and if those twice

the weight play in the same proportion, then the maskalonge is a fish to

be respected.

We camped high up on

the bank of the river, Ellick pitching the tent on the borders of a

clump of pines. As I watched his sober face in the light of the fire, I

wondered at his powers of endurance.

He had been paddling

all day long with the exception of the short luncheon interval, carrying

the stores and canoe over steep and rocky portages, varying the

proceedings by chopping logs, cooking meals and erecting the tent. A

worthy son of that hardy race of Indians who prided themselves in their

strength and won their chieftainship by endurance. It was such youths

who entered the lists and competed in those ordeals that once comprised

the ritual of his tribe. Had the march of civilization in the North-West

continent been stayed or diverted, his physical powers would in all

probability have been displayed in the long-imposed fast in which the

gift bestowed by his guardian spirit was sought. He would have gone

forth to fight unaided the grizzly bear or climb the war eagle’s eyrie

to win the “medicine” talisman essential to his career. Ellick’s

hardihood even suggested an endurance of the most exacting rite in which

the “brave,’' with skewers driven through the muscles of his arms, was

suspended in mid air until a merciful unconsciousness deemed the test

sufficient—a custom no doubt often practised on the banks of that river

where we had pitched our camp.

The fast-waning light

which hung over the scene passed into dark, without the intervention of

a gloaming. The camp fire flickering on the trees only served to make

the darkness visible. Porcupines emerged from their hiding-places in the

wood, loving darkness rather than light. A wild duck’s brood that our

canoe had scattered were re-gathered from amongst the river sedges by

the eager quacking of the mother bird. The musical call of the

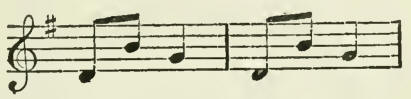

whipoorwill evoked answers from the very heart of the forest:

The notes, oft

repeated, still remain with me. Ellick had spread a bed of balsam

beneath my blankets. It is a species of pine where the needles run in

straight lines, and do not prick or become bulky. There is an aromatic

odour about it which is delightfully pleasant and said to be soporific,

a medicine wholly supererogatory as far as I was concerned. I had

scarcely put my head down when I was off.

How long I slept I know

not, but I was awaked by a sound like a stick drawn sharply round the

canvas of the tent. “What is it, Ellick?” I asked. There was a feeble

answer in which I caught the first and last syllables, por—pine.

Porcupines! The Indian had taken the precaution to bring our provisions

into the tent. But in the morning I learned that, to get at the food at

the head of Ellick’s bed, they walked over my person, and returned by

the same route. I neither heard nor felt them. It may have been the

effect of the aromatic balsam, but an earthquake would not have

disturbed my repose. |