|

“Westward

Ho”—Orangeville—Owen Sound—Through the Great Lakes—Associations of Lake

Huron—Breboeuf’s mission to the Indians—Feast of the dead—The wigwam

life—Indian superstitions—Folklore—Diabolical tortures— Honour—Indian

creeds—Loyola and his followers—Heroism of the Jesuits—Painted devils—Joques—Massacre

of Br£boeuf and Lalemant—Failure of Jesuit mission—The passing of the

Iroquois—Lake Superior—Picturesque rapids—The largest lock in the

world—Sault Ste. Marie—Lake trout—Fishing resorts— An inland sea—The

Rideau River—Nipigon and its trout— Patrol stations—Traffic on Lake

Superior—Thunder Bay—Port Arthur and Fort William—Change of the clock—En

route for Winnipeg—The opening page of the book of the prairies.

EVERY tourist to the

Dominion aspires to visit the Far West. It is the New Canada,

magnificent alike in grandeur and potentialities.

The Canadian Pacific

Railway offers alternate routes. One is by rail all the way, which takes

about four and a half days ; the other by rail and lake, which extends

the journey to two additional days. In the former case the route lies

north of Georgian Bay, Lakes Huron and Superior. In the latter the line

terminates at Owen Sound, and thence the journey is by steamer through

the Great Lakes to Fort William, where the railway course is renewed. It

was this route selected. Although it prolongs the journey, it affords a

break in the long transcontinental trip, and the land-locked seas that

are traversed are the most wonderful on the American continent.

Between Toronto and the

port of embarkation there are many points of interest. At Orangeville

there is evidence that the far-off West is not the only grain-growing

area. Huge elevators show active farming interests. The wide valleys,

sloping away from rising plateaux, yield heavy crops, and the timbered

stretches in close proximity to natural waterways foster the lumbering

trade. Orchards are skirted, laden with fruit, and well-established

farmhouses, nestling among the trees, bespeak plenty and prosperity. A

picturesque cataract makes a glittering streak amongst the green, and

commodious sheds and barns show an advanced stage in farming. At Owen

Sound a rugged headland runs out into Georgian Bay, terminating in Cape

Hund on the western point and Cabot’s Head on the eastern. Here Sidenham

River empties itself into the bay, and imposing cliffs skirt the coast,

whilst the thick green foliage of the woodland contrasts with the

nakedness of limestone quarries.

The steamer course lies

between Cove and Fitz-William Islands, where the waters of Georgian Bay

and Lake Huron commingle. Manatoulin is the chief island lying on the

north side, after which come Cockburn and Drummond.

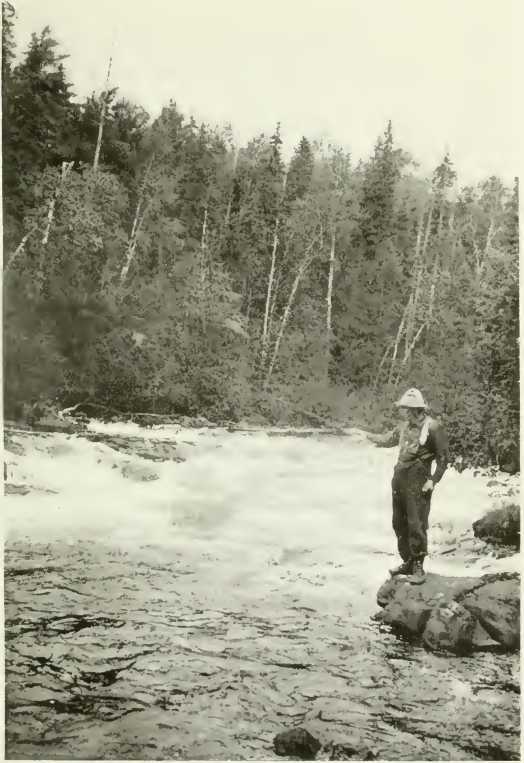

K AKA BEK A FALLS—THE SOURCE OF FORT ARTHUR AND FORT WILLIAM ELECTRIC

POWER

Huron Lake is rich in

historic association. On its shores began one of the greatest human

dramas that the world has known. The dramatis persona comprised the

Jesuits of France and the North American Indians. Faith and

superstition, civilization and savagery, were set in ever-varying

scenes, amidst the wild grandeur of forest and lake until the curtain

fell on the closing act at Lake Erie. It was by Huron lake that Breboeuf

found himself in the seventeenth century, forsaken by his Indian guides.

He, in company with two more Jesuits, had descended the French River,

intent upon forming a mission to the Huron tribes. Breboeuf’s canoe was

separated from his companions’ in the rapids, and he was compelled to

make his way alone to the Indian headquarters. The conditions under

which these tribes lived, the rites he witnessed, and the crude

superstitions by which they were swayed, supplied little for a basis on

which to erect a habitation of the Christian Faith which the Jesuits

came to establish.

In the forest by that

very lake the first missionary witnessed the Huron’s feast of the dead,

and in it may have read the crude shapings of belief in immortality. The

reverence paid to the crumbling bones of ancestors testified to the

belief that a soul resided there. It is an interesting speculation to

consider how Breboeuf was affected by the recital of the virtues and

bravery of the dead to which he listened as these crude children of the

forest made their pilgrimage to the great sepulchre. Would the virtues

of the Christ equally touch them ? He watched the contests in which the

youths so eagerly engaged, and may have discerned in them a spirit of

emulation, worthy of a better cause. It was in honour of the dead that

prizes for these competitions were awarded. The effect on Breboeuf of

the closing scene in the spectacle when the camp fires blazed in the

night and awakened weird shadows amongst the giant trees is on record.

In the drear funeral chant that rose from hundreds of voices over the

bones and weapons piled in the open grave, the Jesuit priest heard a

wail as of despairing souls from the “abyss of perdition.”

These sepulchres, ten

feet deep and thirty feet long, are still to be discovered in the Huron

country. The customs of the tribes were not of the nature to inspire the

Jesuit with hopes, any more than their ceremonies.

Their dwellings

consisted of rows of strong saplings, roofed with bark, which afforded

no privacy and fostered no separate family life. Members of the tribe

could come and go when and how they pleased. Within the circle gossip,

war councils, tortures, vices were practised in turn. The flickering

light of the fire disclosed grizzled warriors, scarred youths, wizened

squaws, gaily bedizened girls, volatile children, and snarling dogs. In

summer the men were almost naked, in winter clothed with the skins

A S1IUSWAT WIGWAM

of buffalo, beaver, and

otter, with rich trimmings of porcupine quills, eagle’s feathers, and

wampum ornaments on State occasions. Marriage was a form without a bond.

It was consummated and dissolved without tears or reproaches on either

side.

But the Jesuits were

not left long under misapprehension of the true nature of the Indian

character. They soon became the horrified witnesses of their cruelties.

Every prisoner of war was subjected to prolonged torture. The victim

would be fed with the choicest food, regaled with a peace pipe, and

exhorted by a chief, a past master in the art of mockery, to take

courage, as he was amongst friends. Even the sweat of fear would be

gently rubbed off his face by the arch mocker. Meanwhile a number of

fires would be lit, through which the prisoner would have to run, whilst

his tormentors, armed with blazing torches, goaded him to greater speed.

Portions of his flesh would be cut off and eaten, and respite given only

to restore failing consciousness. All this continued until death

mercifully proclaimed a final release.

For skill in the art of

torture the females were said to surpass the males, and wherever there

was a case for special treatment the victim was consigned to women. The

diabolical gift probably accounted for the prevalent conception of the

most malignant spirit in the form of a woman. Her robe was supposed to

be made from the hairs of her victims, and the forest fire was the type

of her dwelling-place.

Despite this repulsive

side of the Indian’s character, there were phases that belonged to

another category. Their courage was boundless, and they ranked bravery

above life itself. They suffered in absolute silence, and marched to

their enemies’ fortified positions, knowing that it meant certain death.

Their sense of honour

at times was so great that the perfidy of members of a tribe was

regarded as a disgrace. On one occasion when inter-tribal terms were

under discussion an old chief was known to commit suicide on discovering

a serious breach of good faith on the part of one of his companions.

There was a native

poetry in Huron life that might have seemed promising soil for the

growth of “sweeter manners, nobler laws.” They believed that nature was

peopled with spirits. Tales must not be told in summer-time, when the

spirits were listening and might take offence. Such recitals must be

reserved until nature was locked in ice and snow and their ears were

deaf. The thunder was a bird which caused the lightings to flash in

opening and closing its wings. The violence of the storms was nothing

more than the clamour of the young brood in their nests, and its

mutterings the stooping of the clouds towards the earth to gather up

snakes. Their escha-tology made its appeal to the heroic temperament.

The way to Heaven was

beset with difficulties which the Indians braced themselves to face. It

was represented as a narrow path between moving rocks which each instant

clashed together; or a swift river crossed by a shaking log, and guarded

by a ferocious dog which sought to drive the aspirant into the abyss.

Whilst these crude tenets appealed to courage and perseverance, there

was nothing connected with them that stood for a higher ideal of faith

and conduct. The Indians’ gods were no better than themselves. They were

represented as animated by lust and cruelty; and obedience was

stimulated by sentiments of hatred rather than trust. The worst

passions, not the nobler qualities, characterized these divinities. In

them vice was deified, not virtue. This was the material out of which

the Jesuits sought to fashion a nobler manhood on the shores of Lake

Huron. The conditions were as unpromising as those found by the

missionaries of a later period in Terra del Fuego, the inhabitants of

which Darwin pronounced incapable of either civilizing or christianizing.

And what was the character of the men who undertook the mission to the

North American Indians ? A brief glance at their history answers the

question.

The founder of the

Jesuit order was Ignatius Loyola, a man of singularly composite

character. He embodied in his personality the mixed elements of soldier,

courtier, and zealot. These qualities were reflected in his followers.

Creed and dogma were not propositions that commanded intellectual

assent, but docile obedience. The calm realm of thought was made

impossible in the whirlwind of unthinking action. Dogma was not a thing

to be argued, but enforced, and at any cost—life itself was an

insignificant item in the programme. The shaping of creeds and framing

of morals were not a matter for many minds, but for one superior mind,

in the conclusions of which all others were required to acquiesce.

To suit this spiritual

dictatorship, the ordinary rules of right and wrong were no longer

binding. Black was white and white black if the Superior so willed it.

Zeal being the dynamic of the Jesuit order, exercises were enjoined for

the qualification of the novitiate. He must understand the penalty of

being outside the true fold, and meditate on final things until the

meaning of a lost soul was fully imaged to his mental vision. So

strenuous were these exercises that the disciple imagined he could hear

the howlings of the damned, witness their convulsive agonies, look into

the infernal pit, and tremble at the fire that burned without consuming.

The meditative part of the curriculum covered a course of two years.

Next followed practical training, in which the disciple was required to

undertake the most menial duties in the sick-room and the hospital.

Humility was taught in begging his own bread from door to door; zeal, in

watching his companions for any “tendencies” which were to be

immediately reported, whilst he himself was watched in turn; diplomacy,

in assuming disguises of soldiers, merchants, astrologers and mandarins

for the purpose of making converts and enlarging the flock folded in the

Church of Rome. Only in the light of such discipline is it possible to

understand the sufferings and hardship endured by these first

missionaries to the North American Indians. When prisoners fell into the

hands of their captors, the belief that baptism was all that was needed

to insure eternal bliss no doubt helped to reconcile the priests to the

torture and unspeakable cruelties they witnessed. Indians who declined

baptism when free, submitted to it under torture. The Jesuits regarded

with equanimity any agony that directly led to so desirable a result.

Cases are on record where the priests, themselves prisoners, had the

forejoints of their fingers bitten off by their tormentors, and with

their bleeding hands baptized their fellow-sufferers in their dying

agonies. Under cover of giving drink to a prisoner burning at the stake,

a portion of the water would be spilt on the victim, and the formula of

baptism surreptitiously pronounced.

The eagerness to

perform the ceremony took no account of the character of the subject. A

dying Algonquin threw himself on an Iroquois prisoner and tore his ear

off with his teeth, but the Algonquin was baptized by a priest

immediately after the brutal act.

There was even some

analogy between the Indian practises and the Jesuits’ creed. “You do

good to your friends,” said Le Jeune to an Algonquin chief, “and you

burn your enemies; God does the same.”

Hell was depicted to

them as a place where, according to Jesuit theology, the hungry would

get nothing to eat but frogs and snakes, and the thirsty nothing to

drink but flames. The brutal temperament of the tribes was imitated in

the interests of the Indians’ conversion. The decorations of their

mission church on the shores of Lake Huron were criticized by a priest

as not being sufficiently aweinspiring. “If three, four, or five devils

were painted tormenting a soul with different punishments, one applying

fire, another serpents, another tearing him with pincers, and another

holding him fast with a chain, this would have a good effect, especially

if everything was made distinct, and misery, rage and desperation

appeared plainly in his face.”

Apart from the

crudities and grotesqueness of the Jesuits, stand their splendid heroism

and devotion. One must judge them in the dim light of two centuries ago.

Their conception of truth was the ordinary medieval one in which they

“saw men as trees walking.” Their endurance and self-sacrifice attest

the divinity in man and remain an imperishable memorial. As the steamer

plied along the shore of the great lake, one could see in imagination

these missionaries of the Cross with their faces set in the hopeless

task of reclaiming these children of the forest. Joques, with his

mutilated hands extended in benediction over the heads of the men that

tortured him. We know how he went back to Rome so battered and broken as

to be unrecognizable, but the Indians’ needs haunted him, and he

returned to his mission, to be tomahawked in the end. Breboeuf and

Lalemant, they, too, appear on the scene, lacerated, tortured, the

formula that they had so often used applied to themselves in cruel

derision by their executors. “We baptize you,” they said, pouring

boiling water on their heads, “that you may be happy in Heaven.”

Breboeuf never flinched, although they cut strips of flesh from his

limbs and devoured them before his eyes. “You told us that the more one

suffered on earth, the happier he is in Heaven. We wish to make you

happy because we love you, and you ought to thank us for it.”

Then they scalped him,

and paid the last testimony to his bravery, as emphatic as their

tortures, by drinking his blood that his patience and courage might be

theirs.

So ended the life of

Jean de Breboeuf. France gives him a first place amongst her saints and

martyrs. The roots of his race extend to British soil, for in his veins

flowed the blue blood of the Earls of Arundel.

Great as was the zeal

of the Jesuits, their mission was a failure. Its weak point lay in the

fact that they were more concerned in converting the Indians to the

Roman Catholic faith than in subduing their warlike temper and quelling

tribal strife. Their connexion with the Hurons made the Iroquois— the

enemies of the former—their enemies also. The latter were the most

powerful and warlike of all the North American Indians. Perpetual feuds

were waged between the tribes. The ravages of the tomahawk and the gun

left no room for the cultivation of agricultural pursuits. The Indians

moved from place to place, too restless to take root, paying no heed to

the great natural resources which invited their labour. With the

exception of trapping, all industries were neglected. Wampum was the

only currency they knew, a few beads the highest reward they coveted.

The very principles that the Jesuits sought to inculcate, forgiveness of

injuries, suffering without murmuring, were to the Indians poor weapons

with which to fight their enemies—openly ridiculed by them, and rejected

with contempt. Even when a truce was called between the tribes, and

peace speeches were made, it was only marking time for a fresh outburst

of hostilities.

The final struggle at

Lake Erie practically exterminated the nation that dwelt on its shores.

But the victory was bought at a high price. The battle broke the power

of the conquerors themselves,

PORT ARTHUR. COAL LOADING

whose very name was a

terror to all other tribes. The dead of the victors were as numerous as

those of the vanquished, and the Iroquois never recovered ; as they had

lived by the sword, so they perished by the sword. Their last war-whoop

had been uttered, and their next rally cry evoked no response along the

wild lake-shore.

Lake Superior joins

Huron by picturesque rapids. The narrow confine through which the water

of the great lake endeavours to discharge itself is a seething torrent,

white with anger and beautiful in its wrath.

It is one of the places

where the Indians still display their skill with the canoe whilst

catching trout. To the uninitiated it would seem impossible for a craft

to live in such a current, but the natives negotiate it with impunity.

For the purposes of

navigation a lock has been constructed between Huron and Superior. It is

a triumph of engineering, and is the largest in the world, 900 feet long

and 60 feet wide. It has cost £800,000. Sault Ste. Marie marks the

growth of important industries along the shores. Rolling mills, steel

plant, car factories, and other trades have sprung up there within the

last few years. The St. Mary River flows into the lake at that point on

the borders of the United States, sweeping round St. Joseph Island.

There is good angling

in this neighbourhood, and the trout run to a large size. One served at

the saloon table d’hote, from sectional evidence, must have been 12 lbs.

to 14 lbs. weight. One has a prejudice against large trout, except as a

diversion with a fishing-rod, but the quality of Lake Superior fish as a

comestible is beyond reproach. I have never tasted anything finer. It is

necessary to go inland a few miles to get the best fishing. I had

introductions to local anglers, and reliable information on the subject,

but pressure of time prevented me from breaking the journey. Off the

mouth of the rivers trolling can be had for the big fish, and a few

miles up the streams good fly-fishing can be had.

Sault Ste. Marie is the

connecting point for the Soo Pacific Line which links Canada with the

United States, taking in Minneapolis and the Dacotas. It joins the

Canadian Pacific main line again at Moose Jaw. Superior is the largest

of the American lakes. Its dimensions may be gathered by comparison with

England and Wales, which it could swallow and leave a considerable

margin all round. From the centre, land is out of sight, and it becomes

a veritable sea bounded by the horizon. It is the ocean prairie of

America, and gives the same sense of vastness as its twin sister of the

great plains. The steamer course lies south of Caribou Island, with

Montreal and Leach Islands lying north. The international water-line

which divides Canada from the States proceeds from South Caribou to

MISSANABIE RIVEK. FISHING FOR Sl'ECK LED TROUT

Pigeon Bay via Gull

Island, off Isle Royal. The Rideau River touches the lake at Otter Cove,

and the Nipigon on the same coast further on. The latter is the finest

trout river in Ontario. Three pounds are charged for a licence to fish

it, which is about three times the usual charge. Nipigon runs from the

lake of the same name, and consists of a series of swift rapids that

lend themselves to the highest form of the angling craft. The fish are a

large size, and rise to the fly freely. It is advisable to push up the

river a couple of miles before commencing to fish. Competent Indian

guides can be hired, who know all the pools, and are skilful in the

management of the canoe in the dangerous rapids. Jackfish is another

centre on the coast where angling is procurable. To get the best sport,

a camping excursion is necessary, which can be competently organized by

guides who live at Jackfish, a station on the Canadian Pacific Railway.

On the north shore of Superior, Missan-abie offers all the sporting

advantages of Nipigon, with excellent rapids where, donning waders,

two-pounders can be taking with the fly.

A number of bights off

the coast on the north side of the lake form good harbourage for the

trading boats. Of these, Nipigon Bay, Black Bay, and Thunder Bay are the

chief. It is a storm-bound coast, and at times waves rise and swell in

angry tumult that rival those of the far distant Pacific, breaking

against its islands, and reverberating along the rocky shore. Lake

Superior takes a heavy toll of life, and the bodies of its victims have

been so rarely recovered that it has gained for itself the name of “the

lake that never gives up its dead.” The water is intensely cold on the

hottest summer day.

The centre is said to

be unfathomable, and even along the coast there are enormous depths.

Last summer an engine was struck with a huge rock from the cliffs, and

was swept into the lake. In a depth of 65 feet, a diver reached it, and

recovered the body of the driver. Next day, he went down again, but the

engine had disappeared, leaving the ledge of rock on which it rested,

scarred. The man went down to a depth of 180 feet, but the body of the

missing stoker was never found.

Lighthouses are placed

along the coast, which flash out their warning signals. There are also

patrol stations on cthe look-out for ships in distress. On the State

side, there are regular beats, the eastward and the westward patrols

meeting at stated points, and so establishing a complete surveillance of

the coast.

Soon the steamer drew

away from all landmarks. The water was so smooth that it remained

unruffled except where the prow of the boat broke it into rolling

ripples, or a great lumber or grain vessel left a long white streak

behind.

The number of steamers

that ply on the lake

point to the extensive

traffic which this highway from the Far West affords. We were never long

out of sight of the black smoke line, which stood out in sharp contrast

against the clear blue sky. As evening advanced, the great islands

behind us became mere specks on a far-off water waste, and the chill of

departing day was felt. The sun dipped low on the horizon, and masses of

piled*up clouds glowed as with hidden fire; patches of blue sky were

marked with a tracery of gold and grey. Half buried in the sea the red

disk sank, until the last lingering ray disappeared, and it was night.

The early morning

brought us within sight of Thunder Bay and Sleeping Giant Mountain. Port

Arthur and Fort William at the head of the lake are rapidly rising

towns, anticipating by their enormous grain elevators the corn produce

of the Golden West. These twin ports developing side by side and

presenting the interesting problem to speculative minds as to which

would gain pre-eminence, are the best examples of what railway

enterprise can achieve in connexion with a growing country. Everywhere

there are palpable signs of industry; large trading steamers, extensive

wharves, and coal docks; facilities for loading and unloading, and

transporting the products of forest and field by land and inland sea. It

could scarcely be surmised that Port Arthur only a few years ago was

practically stagnant until it received the initial impulse from the

construction of the Canadian Northern Railway, the youngest of the great

transit systems which marked the beginning of a new era of commerical

prosperity along the shores of the great waterway.

The largest grain

elevator so far constructed is a conspicuous object on the shore. It

holds 7 million bushels of grain. The two ports, between them, have a

capacity for storing 29 millions. Amongst prospective enterprise are

included the construction of a large dry dock and ship-building yards at

Port Arthur. Fort William is the disembarking point of the great lake

trips, and a train stood in readiness to take passengers to the main

line station on the Canadian Pacific. Time changes here from Eastern to

Western methods of chronology, which puts the clock back an hour. The

distinction between a.m. and p.m. is abolished, and the dial of the

clock makes a consecutive rotation from 12 to 24. As a concession to

inbred conservatism and the belief that mortals are slow to learn, the

old and the new modes of reckoning are inscribed on the railway clocks.

For this, one is profoundly grateful. One scarcely knows where he is

when, on asking the time of day, he is told that it is twenty-three

fifteen!

The railway journey to

Winnipeg epitomizes all that lies behind and before—a rocky region

intersected with rivers and lakes; forests stretching away out of sight;

mining industries locked in the great mountains; falls that rival

Niagara in magnificence, and all the branches of industry, from the

Government experimental farm at Dryden to the great water-works at

Keewatin. There the Lake of the Woods, 3000 square miles, furnishes the

greatest water dynamic in the world. As the train nears Winnipeg, the

introductory chapter in the encyclopaedic volume of the prairies begins,

and many days will have to be spent in looking through its pages. |